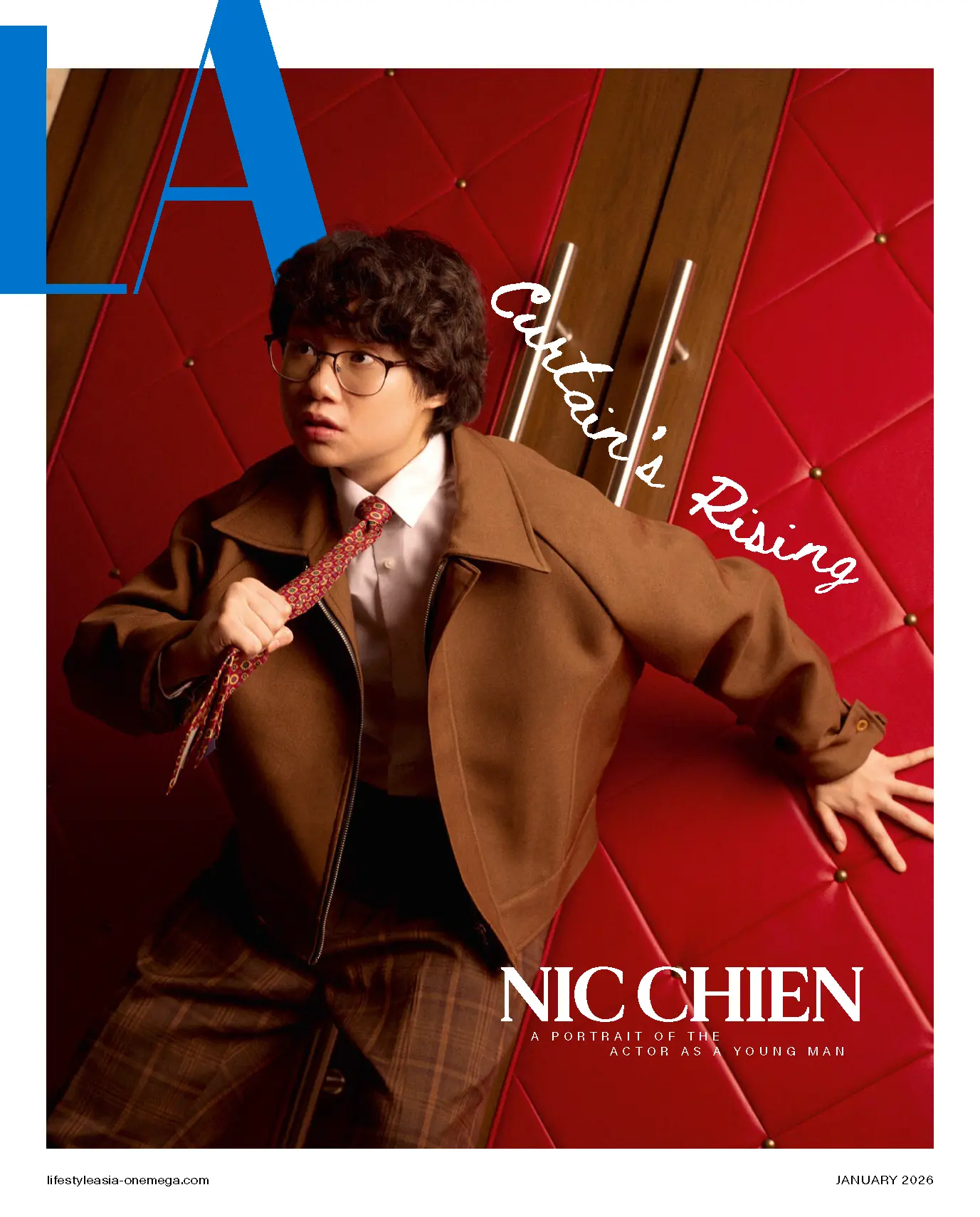

The old-world love story behind Manila’s most beloved noodle soup, mami, and the multi-generational legacy of its founder Ma Mon Luk—told through the memories of his son and granddaughter who carry on his traditions.

Once upon a time, in a land called Binondo, a young man named Ma Mon Luk roamed the streets, peddling his own take on chicken noodle soup–what he called mami. It was the late 1910s, and this poor immigrant from China arrived penniless but determined to rebuild his life after the parents of the woman he loved deemed him too impoverished to marry their daughter. Armed with little more than a recipe and a broken heart, he unknowingly set the stage for a revolution in Filipino-Chinese cuisine.

More than a century later, countless bowls of Ma’s original noodle soup continue to warm the hearts and stomachs of Filipino diners from all walks of life. Though simple in its components, it is a dish steeped in history, telling not just the story of the Filipino-Chinese experience but of a grand romance that birthed both a family and a culinary legacy. To this day, Ma’s youngest son, George Mamonluk, and his granddaughter, Georgia, keep this story alive, recalling a patriarch whose fairytale life is part of every steaming bowl.

READ ALSO: Paz Marquez-Benitez: A Filipina Literary Icon and Pioneer

A Humble Bowl of Soup

For centuries, even before colonial rule, Chinese merchants and immigrants had already established communities in the Philippines, creating vibrant commercial and cultural connections. Recognizing this established Chinese presence, Governor-General Luis Pérez Dasmariñas officially designated the area Binondo as a settlement for Chinese converts in 1594, formalizing what would evolve into the world’s oldest Chinatown. As this bustling district grew, news of its thriving business scene spread to China, inspiring many to make the journey.

Among those drawn to Binondo’s promise was Ma Mon Luk, a humble schoolteacher from Guangzhou who arrived in 1918. In China, he had fallen for Ng Shih, but her family’s rejection of his suit drove him across the sea in search of a fortune that might transform him from unworthy suitor to acceptable son-in-law.

With unwavering determination, Ma soon established a modest food business on the streets of Binondo and Sta. Cruz. He would carry two large metal containers balanced on a long bamboo pole across his shoulders. One held his homemade chicken broth, while the other carried freshly kneaded noodles and pieces of cut chicken. He also brought bowls and utensils, allowing him to serve customers on the spot.

Whenever a curious passerby stopped to try his dish, he would simply cut the noodles with scissors—a technique he called gupit—place them in a bowl with chicken, and ladle in steaming broth, kept hot by live coals beneath the container. With practiced ease, he served his creation, winning over locals one bowl at a time.

“He would walk the streets of Manila, personally handing out free samples of his food to get people to try it,” George shares, pride evident in his voice as he spoke of his late father. “He believed in his food so much that he wasn’t afraid to approach strangers, talk to them, and convince them to give it a chance. Little by little, he built a following, and that persistence eventually led to the restaurant we all know today.”

This dish grew in popularity over time and is now famously known in the Philippines as mami. “Mami actually means ‘Ma Mon Luk’s noodles’—‘Ma’ for Ma Mon Luk and ‘mi,’ which translates to ‘noodles’ in Chinese,” George explains.

Mami as a Household Name

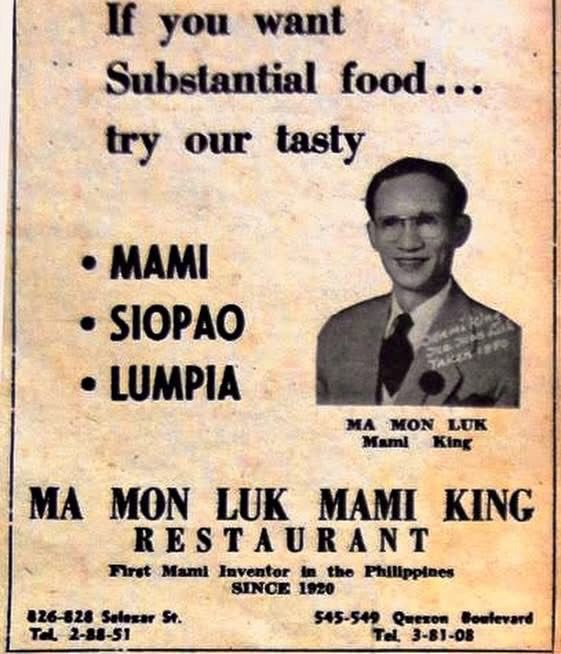

After years of peddling his beloved mami noodles, Ma opened a small eatery on Tomas Pinpin Street. The space had only two tables, but the savvy businessman was determined to take it to the next level. He expanded the menu, introducing his signature siopao—still a bestseller today—along with his secret sticky sauce.

Even after opening his eatery, Ma continued to roam the streets, promoting his business by handing out free siopaos. His hard work paid off, and he soon reaped the rewards of his success. Not only did he save enough to open his first official restaurant on Salazar Street in Binondo, but he also returned to China as a wealthy man to marry his true love, Ng Shih.

By the mid-1950s, Ma Mon Luk and his mami had become household names. The small restaurant on Salazar Street expanded to a second location on Quezon Boulevard near Quiapo, which Ma purchased. Above the restaurant, he made his home, where he and Ng raised their four children: George, William, Robert, and Irene. Mami not only united two lovers but created a family dynasty that would carry his legacy forward.

“One of my clearest memories is of him sitting in the restaurant, watching customers enjoy their meals,” George reminisces. “He wouldn’t say much, but you could see the quiet pride on his face. He built this from nothing, and I think he found real joy in seeing people come back, bowl after bowl, generation after generation.”

And indeed, generation after generation, they returned. The restaurant in Quezon City remains as busy as ever, with a line of loyal diners forming outside even before the metal gate is opened. Once it rises, people pour in, eager to take their seats and order from the simple menu placed on the table, listing three types of mami, four kinds of siopao, and their signature siomai.

Today, mami is still prepared the same way as Ma had done it all those years ago, with only a few modern conveniences added. At the heart of the open kitchen stands a large metal vat, brimming with master broth—continuously enriched and replenished as the days go by. Beside it, rows upon rows of bowls filled with hand-pulled noodles and chicken (along with pork, a more recent addition) sit ready, awaiting a rush of steaming broth the moment a diner orders.

Waiting for the food, though it only takes minutes, feels like a glimpse into the old world. The walls are lined with vintage advertisements and countless newspaper and magazine clippings chronicling Ma Mon Luk’s rich history over the decades. The tables remain simple—either marble or wood—unchanged by time. The place has never been renovated, holding fast to its old-world charm.

And then, there’s the aroma—warm, savory, and irresistible. Broth simmers over low heat while stacks upon stacks of bamboo steamers gently release clouds of fragrant steam as it cooks buns and dim sum to perfection. This was where Ma once ate and stood 70 years ago, and the nostalgia lingers.

The No-Frills Legacy of Ma Mon Luk

Ng stayed happily married to Ma until he passed away from throat cancer in 1961. The family kept his business and legacy alive. Their children took over, preserving the original recipes and traditional methods of preparing mami and siopao to ensure their quality and authenticity remained unchanged. By the mid-1990s, his children had expanded the business to six locations across Metro Manila. Today, the brand maintains a relatively low profile, with George overseeing the day-to-day operations of the remaining Quezon City branch.

Ma Mon Luk’s impact on local cuisine is undeniable. His success not only popularized siopao and mami in the Philippines but also inspired countless imitators, paving the way for many Filipino-Chinese eateries.

“These dishes weren’t mainstream yet, but because of Ma’s popularity, they became part of everyday Filipino culture,” says George. “What’s also special is how Ma Mon Luk blended Chinese culinary traditions with Filipino tastes. The broth in our mami, for example, has that deep, rich flavor rooted in Chinese cuisine, but it’s also adjusted to suit the Filipino palate—comforting, hearty, and familiar. The same goes for our siopao, which became a go-to merienda or snack for so many people.”

When asked why he believes the legacy of Ma Mon Luk has endured, George attributes it to serving simple, authentic dishes with a no-frills appeal. They don’t follow trends; they simply stick to what’s best—Ma’s original recipes. “It’s amazing how word-of-mouth has kept it alive,” he says. “Families pass down the tradition of eating there, and before you know it, it becomes part of their family history too. In a way, it’s not just about the food—it’s about the memories tied to it.”

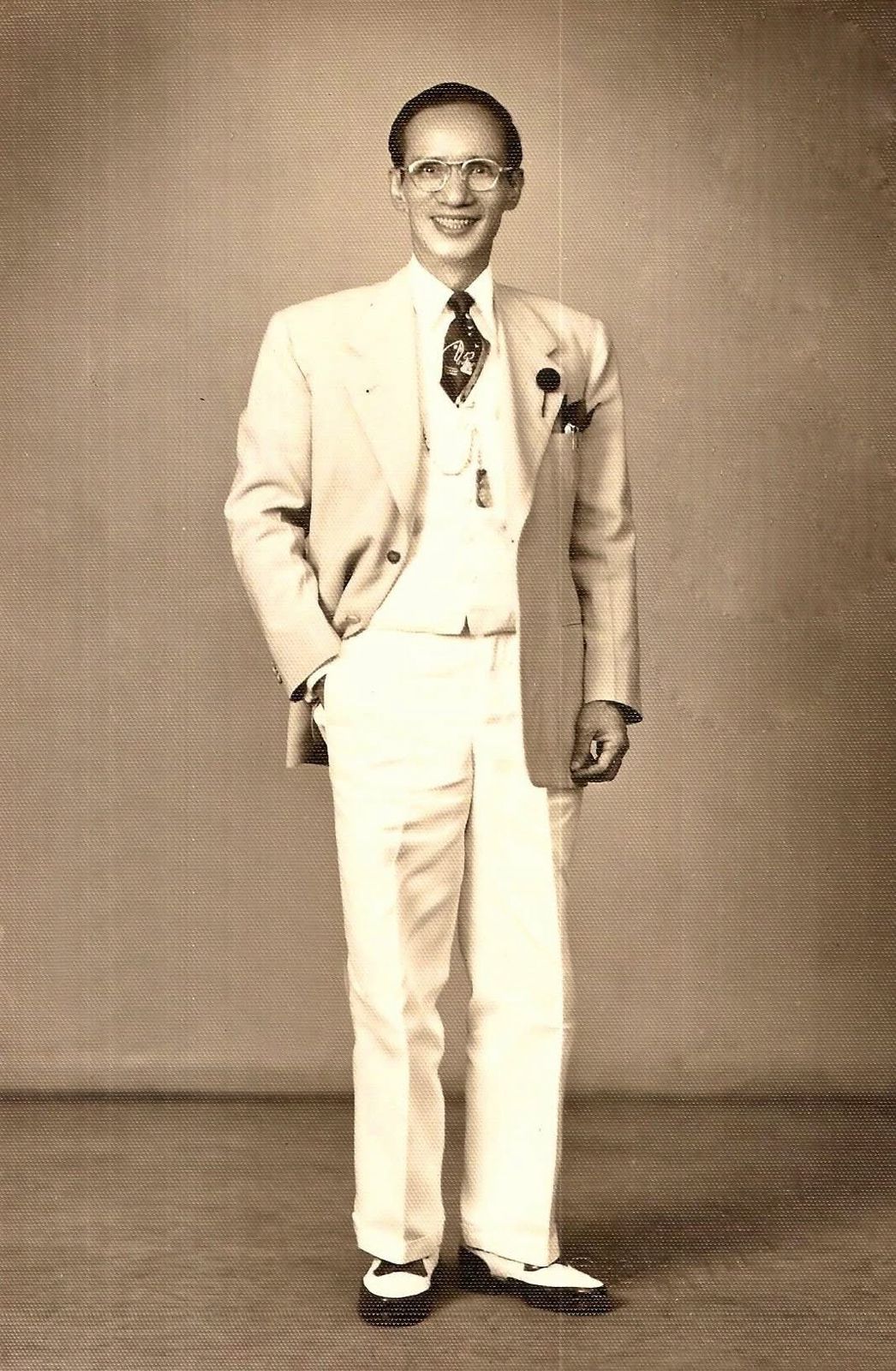

George’s eldest daughter, Georgia, an entrepreneur and owner of bone broth business The Broth Bar and charcuterie store La Platteria, chimes in: “You know, growing up, I always knew my grandfather was someone special, but I don’t think it truly hit me until I saw how deeply people connected with his food. I remember one moment—I must have been in my early teens—when I was at one of the restaurants and overheard an older gentleman telling his grandson how he used to come here with his father. He talked about how my grandfather would walk around in his signature suit, personally serving customers and making sure everyone felt welcome.”

She continues, “That was when I realized Ma Mon Luk wasn’t just a name on a restaurant sign—he was a part of people’s lives, their traditions, and their memories. His food wasn’t just food; it was comfort, nostalgia, and a bridge between generations. At that moment, I understood—he wasn’t just my grandfather; he was a cultural icon whose legacy lived on in every bowl of mami and every bite of siopao.”

READ ALSO: The History of Rita Moreno’s Oscar Win And Iconic Pitoy Moreno Dress

Noodles of Wisdom From The Mami Man

Even at the height of his success, Ma Mon Luk remained the same man who once peddled mami on the streets of Manila, offering a bowl to anyone willing to try.

“He always showed a deep sense of community and generosity,” George says. “Ma Mon Luk would personally go out and give siopao to families affected by fires and floods. He knew how difficult times were and wanted to offer comfort, even if just for a moment, with something familiar and warm. He had this quiet way of helping—never seeking attention or praise—but you could see how much he cared for the well-being of others.”

This kindness and spirit of generosity live on today, with his granddaughter Georgia seeing Ma’s legacy as more than just the recipes he left behind—it’s in the way people remember him. “My grandfather didn’t just serve food; he made people feel like they were part of something special. That’s something I try to do as well,” she says. “And while I never met him, his story has taught me so much—about resilience, consistency, and the power of personal connection.”

And perhaps that’s why people keep coming back to Ma Mon Luk after all these decades. It’s not just about the food—though a bowl of mami or a freshly steamed siopao still tastes just as good as the last. It’s about tradition, nostalgia, and the stories passed down through generations. In every sip and slurp, a fairytale continues to unfold—one that began with love, persevered through hardship, and found its happily ever after in the most unexpected of places: a humble bowl of soup.

This article was originally published in our April 2025 issue.

Photography by Ed Simon of KLIQ, Inc.

Additional photos courtesy of the Mamonluk family