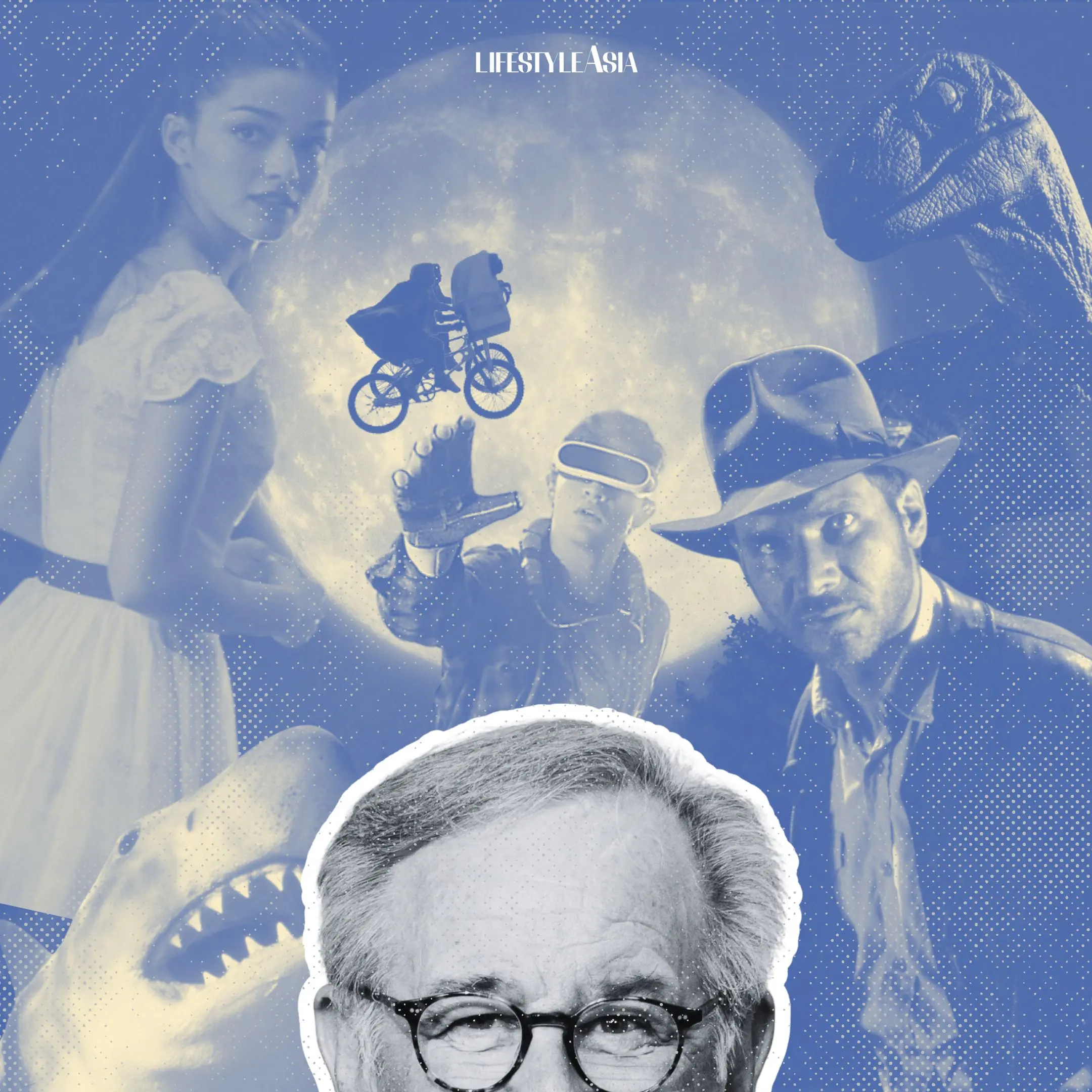

I didn’t set out to find meaning in Steven Spielberg’s work—I just wanted something to do. But the more I watched, the more I realized: his films were quietly offering a philosophy for living.

It was the height of the pandemic, and truthfully, there wasn’t much to do. Remote work kept us busy in theory, but without gatherings, spontaneous outings, or even the routine of outdoor workouts, time stretched endlessly within the walls of home. In 2020, Steven Spielberg—arguably the most influential figure in Hollywood—was set to release his long-awaited adaptation of West Side Story, a beloved Broadway musical immortalized in the 1961 film that had taken home the Oscar for Best Picture.

As a fan of the original movie, I was eager to see what Spielberg might bring to this timeless tale. But like nearly everything else in that uncertain period, the film’s release date was delayed by a full year. My little cinephile heart ached. What now? With so much time and nowhere to go, I figured: why not prepare myself? Why not watch all 35 feature films directed by Spielberg, in order? If there was ever a time for a cinematic pilgrimage, it was now.

Fortunately, most of his films are immensely popular and culturally significant, which made it easy to source everything legally. I already owned many of his most iconic works on Blu-ray—like Jaws and Jurassic Park. And as an avid movie fan, I’ve always enjoyed having physical copies of films I love. Even lesser-discussed titles like Empire of the Sun and Minority Report were already sitting on my shelf. All it took was popping in a disc.

I wasn’t surprised to find that many of Spielberg’s films were available on local streaming platforms like Netflix and HBOGo (HBOMax would come years later). He is Spielberg, after all. At the time, it was easy to stream titles like The Terminal, War of the Worlds, Saving Private Ryan, and The Color Purple (which I do own on DVD but was too lazy to dig out, so Netflix it was). The more obscure titles, like Always and The Sugarland Express, took a bit more effort to find. Thankfully, other equally bored cinephiles were trading their collections online, so Facebook Marketplace became my unexpected best friend.

READ ALSO: 15 Best Picture Oscar Winners Currently Streaming In The Philippines

The Steven Spielberg Cinematic Odyssey Begins

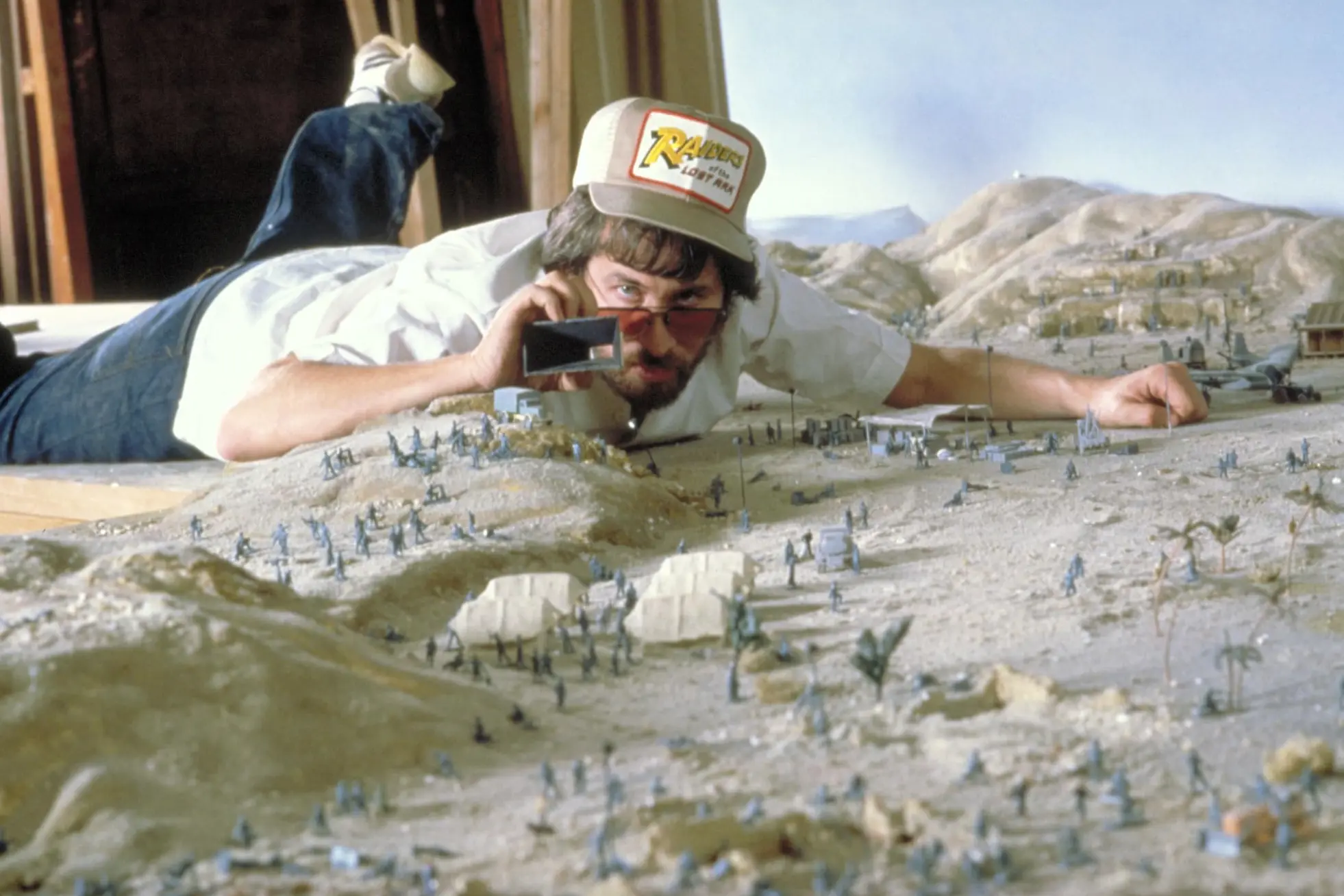

Watching Spielberg’s first two films—Duel and The Sugarland Express—revealed startling clarity in his filmmaking instincts, even at such a young age. Both films, essentially extended car chases, showcased the flair of an emerging director capable of transforming the ordinary into the mythic. Duel, in particular, played like a parable of fear and isolation, and eerily resonated with the pandemic I was living through. It struck me then: maybe this marathon wouldn’t just be a way to kill time. Maybe it would be a way to make sense of it.

What followed was a cinematic odyssey I’ll never forget. Each film I watched revealed something new about the director and his perspective. My newfound obsession led me to research what Spielberg was experiencing during the creation of these works. For instance, he was reflecting on his parents’s divorce when making E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, both of which deal with themes of alienation and longing for connection.

He was striving to be recognized as a serious filmmaker—not just a commercial powerhouse—when he tackled The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun. Jurassic Park, a film about humanity’s attempts to control nature, was also about Spielberg’s own struggles with commitment. Films like Munich and The Post were his way of critiquing the political climate of the time, capturing the tension of global conflict and the moral complexities of leadership.

And I can’t forget about “late Spielberg,” marked by a more reflective turn in his filmmaking. Ready Player One, overflowing with ‘80s pop culture imagery, was his way of reconnecting with his roots and embracing nostalgia. And as I learned more about it, I realized West Side Story was a tribute to his childhood, as the original cast recording had played constantly in his family’s home.

Then, in 2022—long after my marathon had ended—Spielberg released The Fabelmans, an autobiographical film about his youth. Gabriel LaBelle plays a young Spielberg, thinly veiled as Sam Fabelman, chronicling how he discovered the magic of movies and turned filmmaking into a way of escaping, and ultimately confronting, his problems. For me, this was a cinematic gift because it tied the entire pilgrimage together. It was Spielberg reflecting on Spielberg, through film. Everything I had read and researched about him came alive in this masterful two-and-a-half-hour portrait that revealed all his nuances.

In short, there was far more to Spielberg than I had realized. He wasn’t just a director of blockbuster hits; he was a man deeply engaged with the world around him, trying to say something profound through his work. Spielberg’s films were reflections of his own journey, each one shaped by his personal experiences, fears, and hopes.

In return, Spielberg taught me about life. His films didn’t just entertain me—they reaffirmed lessons I needed to hear. The themes in his work resonate with everyday people. Each story centers on an ordinary individual thrust into extraordinary circumstances—something we all experience in our own way. It didn’t matter that his films often included fantastical elements, like a young boy befriending an alien or a teenager fleeing the FBI (or perhaps running from his parents’s divorce); at their core, they remain deeply human.

Spielberg had much to say about life, and here are five key lessons I learned by watching all of his films.

Life Lessons From Steven Spielberg:

Lesson 1: Every Life Is Extraordinary

At the center of most Spielberg films is an ordinary person whose life is suddenly upended by something extraordinary. Off the top of my head: Albert, from War Horse who is thrust into the horrors of World War I; Frank Abagnale Jr., a seemingly average teenager who cons the U.S. government out of thousands in Catch Me If You Can; and Chief Martin Brody in Jaws, who must protect his seaside town from a monstrous great white shark. Even Indiana Jones fits the mold—a college professor with a side job unearthing ancient artifacts.

Of course, there are exceptions. Spielberg made a biopic about Abraham Lincoln in 2012, one of the most celebrated presidents in American history. He also gave us David, the robot child in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, who embarks on a quest to become “real.” But even these larger-than-life characters are treated with the same emotional depth and empathy as the more grounded ones. Spielberg films see greatness not as a matter of status, but of spirit.

It makes sense—he grew up in a middle-class household, the child of divorced parents, before becoming a multiple-Oscar-winning billionaire. He knows what it’s like to come from somewhere “ordinary.” And perhaps that’s why, no matter the story or genre, he returns to one essential truth: every life is worth living, because it’s uniquely yours.

Spielberg’s ability to merge the extraordinary with the deeply personal taught me that wonder lives within the mundane—and that all of us are capable of greatness, no matter the odds.

Lesson 2: Nostalgia And Sentimentality Is A Good Thing

One of the main criticisms Spielberg has faced throughout his career is his tendency to lean toward nostalgia and sentimentality. Major critics have often called him out for this, accusing his work of being overtly sappy rather than truly profound. But if you look closer, Spielberg’s nostalgia is not a flaw—it’s a strength. He doesn’t use sentiment as an escape; he uses it to process the past and share something deeply personal with the world.

Understanding Spielberg’s turbulent childhood, his parents’s divorce, and his early insecurities as a filmmaker puts this into perspective. His use of sentimentality isn’t a cheap trick—it’s a means of conveying emotional depth and storytelling with purpose. Films like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind may appear at first to be simple sci-fi blockbusters with sappy endings, but beneath the surface, they’re personal reflections on abandonment, obsession, and longing for connection. E.T. centers on a broken family and a boy dealing with his father’s absence, while Close Encounters explores the emotional fallout of a man who, like Spielberg’s own father, becomes consumed by his work.

What Spielberg shows us is that nostalgia and sentimentality—when used thoughtfully—can be powerful tools for healing and self-realization. They don’t just romanticize the past; they help us understand it, feel it more deeply, and move forward. His films remind us that it’s okay to revisit the past if it helps us make sense of who we are today.

READ ALSO: The History of Rita Moreno’s Oscar Win And Iconic Pitoy Moreno Gown

Lesson 3: Art Truly Reveals The Artist

Throughout this essay, I’ve already mentioned how Spielberg’s work offers insight into who he is as a person. It’s important to emphasize this point because many people view his films as simplistic, light-hearted entertainment without deeper significance. But if you study his filmography as a whole, you’ll notice that his work reveals much more about him as an artist.

Many of Spielberg’s films feature a deep connection to Jewish culture and religion—something he struggled with during his childhood, particularly due to bullying. He is often drawn to World War II themes, with many of his works focusing on the defeat of the Nazis. The Indiana Jones series, for instance, frequently depicts Nazi antagonists, especially in stories set during the Holocaust era. Films like Saving Private Ryan and Munich also engage with Jewish themes, reflecting Spielberg’s personal and cultural heritage.

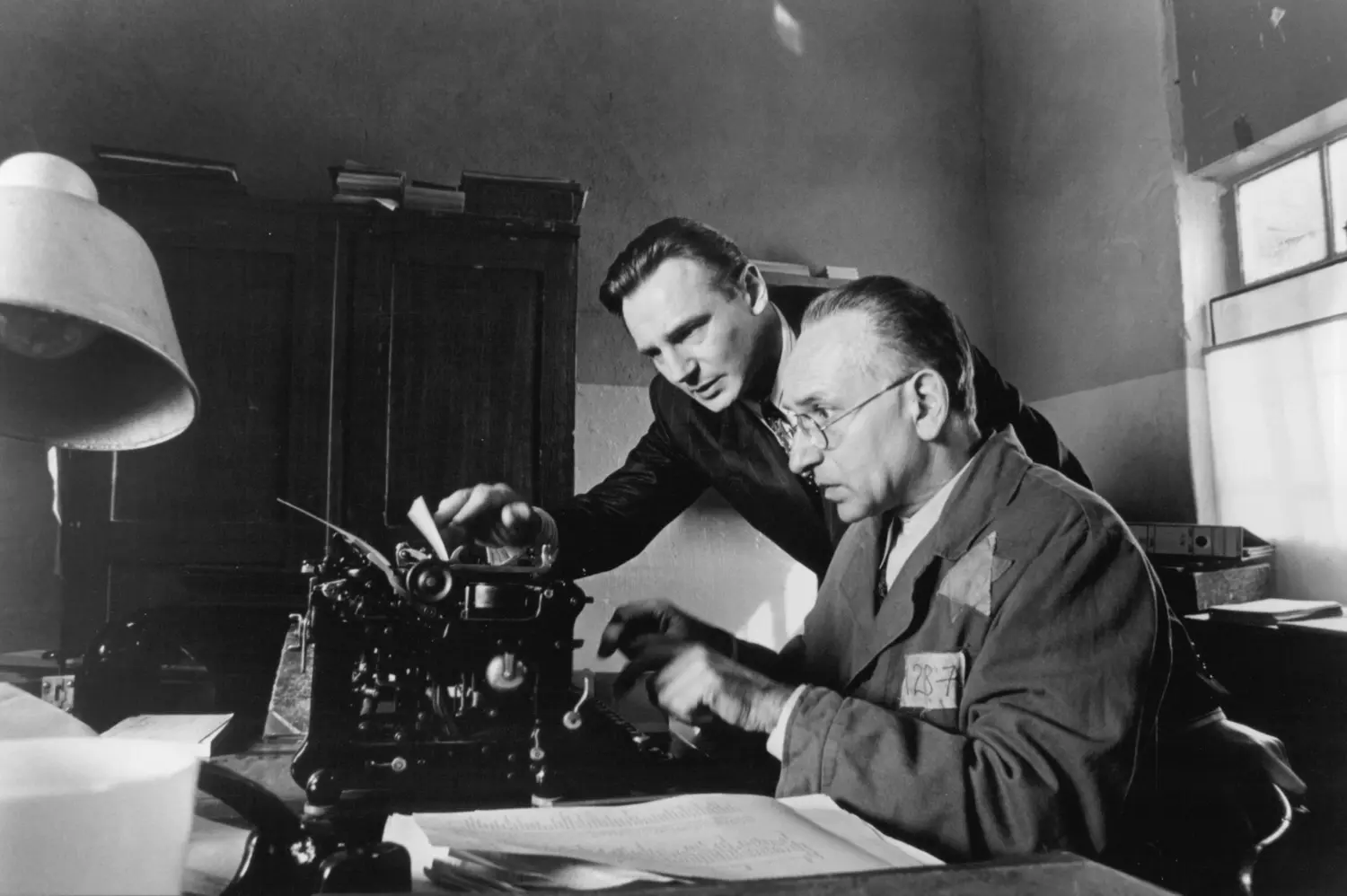

Less overtly, historians suggest that other films—such as The Sugarland Express and Close Encounters of the Third Kind—serve as ways he processed his Jewish insecurities, often through characters on the margins of society. Schindler’s List, his most acclaimed film, confronts the Jewish experience in its most extreme historical form. Decades later, The Fabelmans would turn inward, exploring Spielberg’s personal struggles with Judaism during his teenage years.

There are plenty of other examples outside religion, such as Spielberg’s commitment issues—depicted in Jurassic Park—and his difficulty letting go of his parents’s separation in his youth. But the main lesson here is that you should never judge a book by its cover. Art truly reveals the artist, so take a closer look to understand the deeper meaning behind it. This applies not just to Spielberg, but to the people around you as well. When someone creates or expresses something, what are they really saying? For example: what does my act of writing this essay reveal about me?

Lesson 4: Spielberg Knows That Childhood Matters

Spielberg’s films have launched the careers of many child actors who continue to thrive today. He discovered Henry Thomas and Drew Barrymore in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, introduced Academy Award winners Ke Huy Quan and Christian Bale in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Empire of the Sun, respectively, and more recently cast Rachel Zegler in West Side Story and Gabriel LaBelle in The Fabelmans. He also helped cement the reputations of Haley Joel Osment (A.I. Artificial Intelligence), Leonardo DiCaprio (Catch Me If You Can), Tye Sheridan (Ready Player One), and Dakota Fanning (War of the Worlds).

But why are children so central to the Spielberg universe? Because he sees childhood as the most formative part of life.

In The Fabelmans, we glimpse Spielberg’s own early years and see how profoundly they shaped him. In his films, children are never caricatures—they’re complex, emotionally rich individuals, often more perceptive than the adults around them. Spielberg believes children should be understood, and through his storytelling, he gives them center stage and surrounds them with wonder.

So what does that teach us? That children—and childhood—matter. As adults, we shape the young people in our lives. A little kindness and understanding goes a long way. When we nurture childhood, we help raise better, more rounded people. Be kind to the young. Make their childhoods magical.

READ ALSO: Romance in Technicolor: Five Films From The Golden Age of Hollywood To Fall In Love With Again

Lesson 5: Fear Is Part Of The Journey

Everybody gets scared—even the lead character of a Hollywood movie. One of the most compelling aspects of Spielberg’s work is that his main characters are always emotionally complex and deeply flawed (well, maybe not his Abraham Lincoln). But the point is this: Spielberg is never afraid to show his characters’ vulnerability, even when they’re positioned as traditional heroes.

Indiana Jones is terrified of snakes. Tom Cruise, the quintessential action star, spends most of War of the Worlds in a state of panic as Ray Ferrier, a man desperately trying to protect his children. Meryl Streep’s formidable publisher, Katharine Graham, is paralyzed by fear of ruining her family’s legacy when she must decide whether to publish the Pentagon Papers in The Post. Whoopi Goldberg’s Celie, in The Color Purple, is constantly consumed by fear due to her abusive husband. Even Peter Pan, played by Robin Williams in Hook, is scared—because he’s forgotten who he is.

Spielberg understands that fear is an essential part of the human journey, one of the things that shapes us most profoundly. His films remind us that fear can be overcome—with a little courage. Indy always pushes through his phobia. Ray Ferrier protects his family. Katharine Graham makes the brave decision to take a stand. Celie finds her agency and stands up for herself to build a better life. Peter Pan reclaims his identity.

Through courage, we grow. We transform. We become more of who we’re meant to be. Watch any Spielberg film and you’ll walk away feeling more deeply human. You’ll witness people confronting the impossible—and you might just believe that you, too, can rise to meet your own challenges and soar.

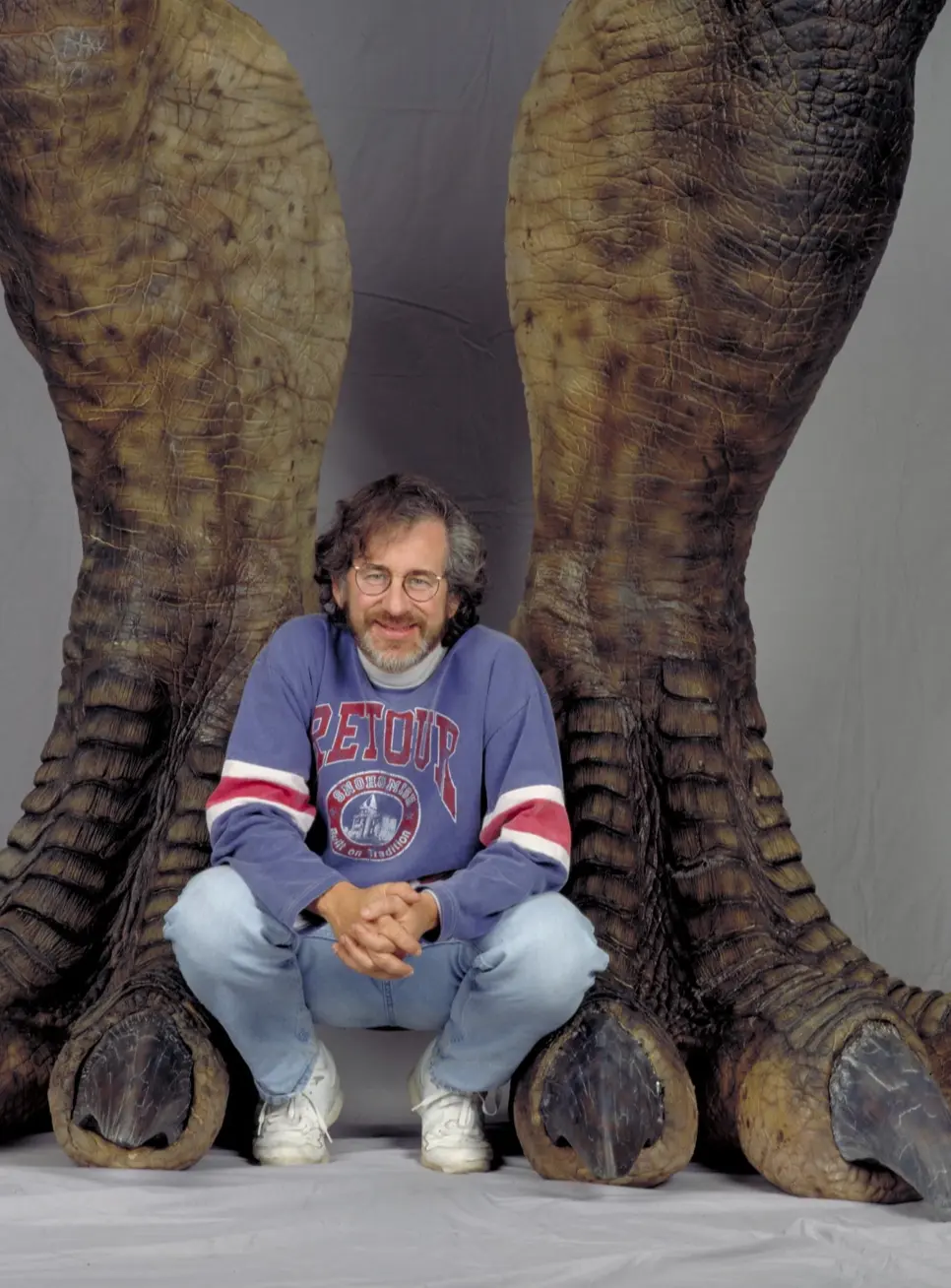

Solo portrait in banner courtesy of Wikipedia.