The barong Filipino’s rise as the nation’s emblematic garment is a fairly recent development within a storied history—and it has a lot more to do with past Philippine presidents than we think.

The iconic barong, or “barong Filipino” as it’s now referred to, has come a long way. Today, it’s a fairly common wardrobe staple, worn with pride on nearly every occasion from weddings to work. But its status as the country’s national attire is a fairly recent one, despite how ingrained the piece is in our collective consciousness.

In fact, its evolution and popularity are inextricably tied to our nation’s steady climb towards independence; in the same vein, the Philippine presidents who bore witness to these periods of history, and made history themselves, also had a hand in changing our perceptions and takes on the garment.

Lifestyle Asia sat down with costume designer and scenographer Gino Gonzales to better understand the garment’s history and how the country’s leaders have influenced the attire we’ve all come to know and love.

READ ALSO: Fashion’s Living Archives

The Basics: Defining The Barong Filipino

Defining the barong can be tricky, given its continuous evolution. In the book Garment of Honor, Garment of Identity, Ma. Corazon Alejo-Hila, Mitzi Marie Aguilar-Reyes, and Anita Feleo define it as a “translucent tunic that falls midthigh and is slit on the sides.” It also has a collar; straight, long, cuffed sleeves; and recognizable, fine embroidery “usually girding the garment’s opening from neck to waist” (which is referred to as the pechera, from the Spanish word for “chest,” pecho).

However, the barong’s versatility has yielded modern iterations that don’t quite fit this mold, which means we’ll need to keep searching for more consistent criteria. For instance, not all barongs have a collar, long sleeves, or even cuffs, and some have minimal embroidery.

For Gonzales, a garment should, at the very least, if all other characteristics are absent, be translucent or sheer to be defined as a barong. By extension, it should utilize fabrics that possess this characteristic, such as the traditional choices of piña (a textile made from fine pineapple fibers) and jusi (a semi-transparent fabric derived from fine silk threads). “It doesn’t matter how elaborate it is; I think it just has to have a see through quality to it,” he shares.

From Baro to Barong: Tracing A Garment’s History

The barong has pre-colonial roots, so many of the anecdotes surrounding its origins and early history tend to be apocryphal. That said, scholars have attempted to piece together a cohesive history from the fragments of evidence presented in early documents and accounts of the archipelago, as well as debunk the myths that cropped up over the centuries.

The baro is a generic term for the upper garments of both sexes, according to Gino Gonzales. It was a loose, long-sleeved collarless tunic that extended slightly below the waist, normally made from canga (a rough cotton cloth). The pre-colonial men of Ma-i (what the Philippines was called before the Spanish arrived) often paired the baro with a loincloth (bahague), while women wore it with a wraparound skirt called tapis.

However, it wasn’t the most favorable outfit, especially for the men, as it hid their tattoos—traditionally symbols of pride and honor (the Spaniards referred to them as pintados).

Yet the sentiment of the newly-baptized Filipinos toward the baro quite possibly changed when it became one of the few ways they could express themselves, as the Catholic faith required them to dress

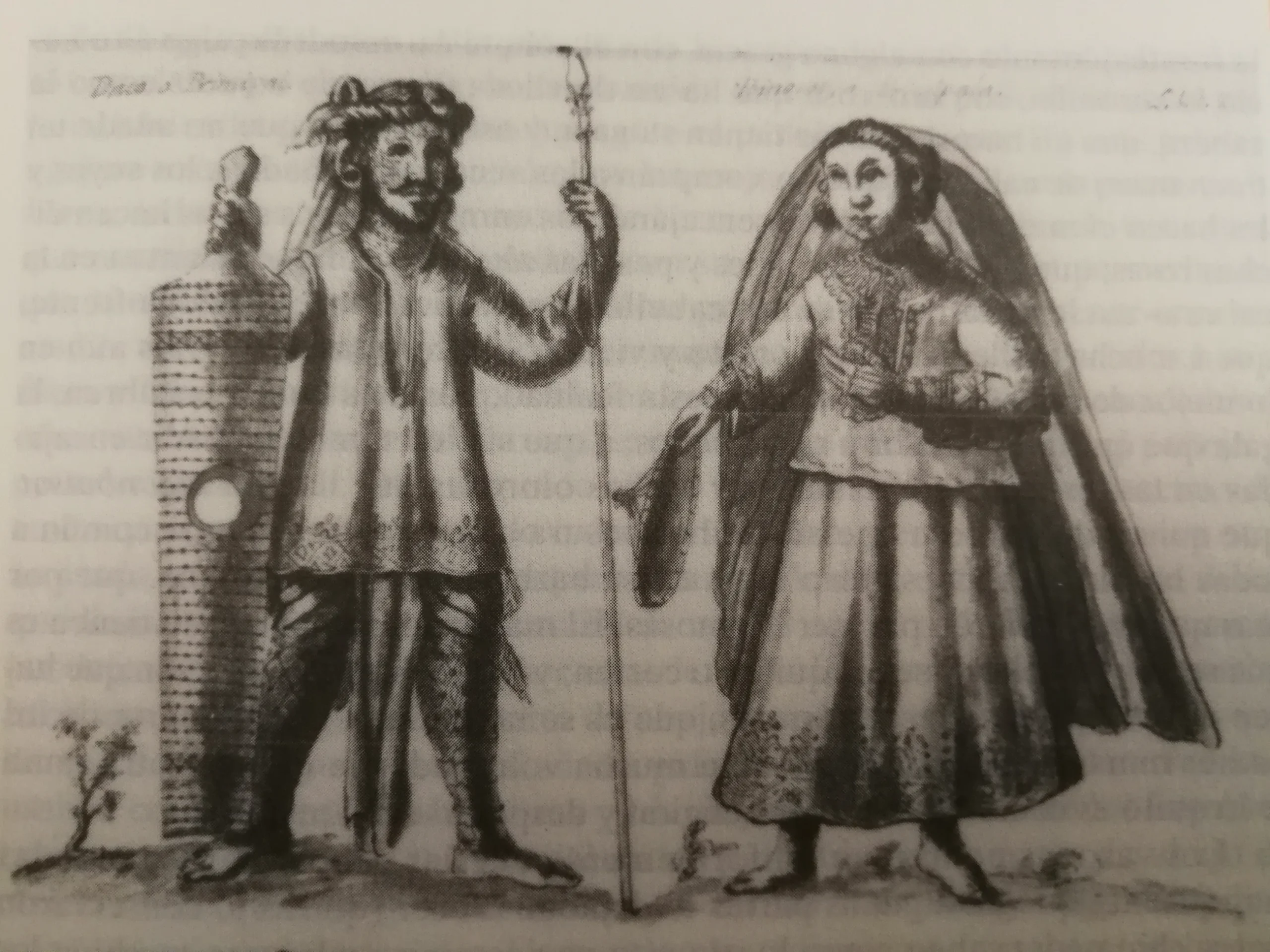

modestly. Gonzales admits there’s a “dark period” in the research of barongs, especially during the 1600s to early 1700s (roughly after we were colonized by Spain), but cites Jesuit missionary Francisco Ignacio Alcina’s account History of the Bisayan People in the Philippine Islands as a telling resource.

“In the book, you can see a drawing of a man wearing a barong: he still has his tattoos, so it’s a very transitional garment that he was wearing. But you can also see that he already has a pechera or an embroidered chest piece,” Gonzales expounds. “When tattoos were forbidden, something had to replace them. Supposedly, the embroidery or motifs that were once on the body were transferred onto an outer shell, which is the barong.”

This is a tentative conclusion or theory, but a compelling one nonetheless, showcasing how even the barong’s most nascent form held a special significance in the lives of early Filipinos. Under European influence, Filipinos would later switch to trousers, and the baro would continue to take on many forms and names depending on the communities who’d wear them.

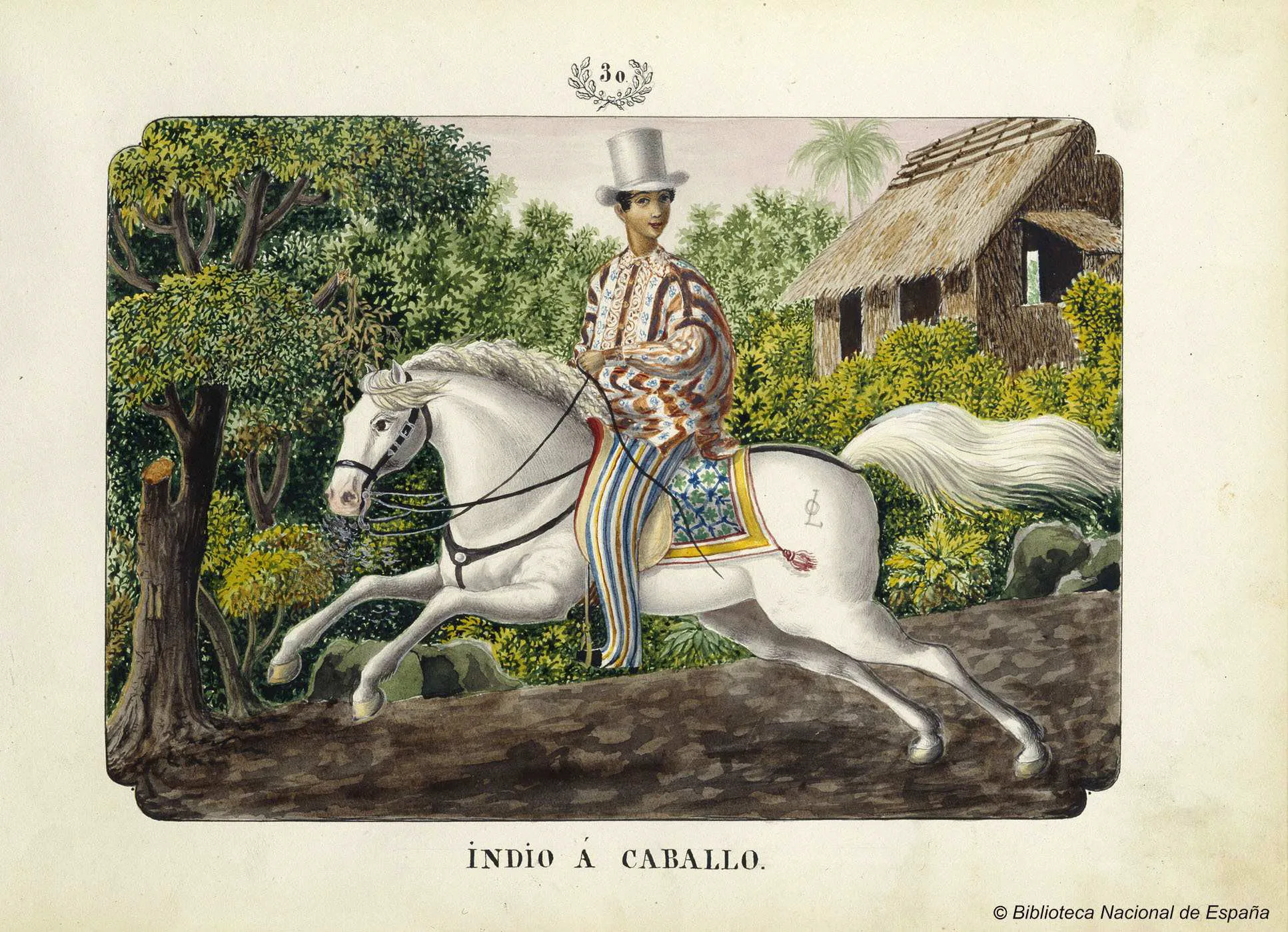

In the 1800s, when an influx of new wealth began to create sharper class distinctions among Filipinos, the country’s elites wanted to distinguish themselves by creating their version of the thicker baro worn by those in the lower strata (at this time, typically beneath a camisa de chino or white undershirt). They did this by incorporating piña fabric into the garment—a material introduced after the Spanish brought pineapples to the country, possibly through the Manila-Acapulco galleons.

By the 1850s, the elites almost always wore a translucent baro of piña or jusi with delicate, intricate embroidery; this was the time when techniques like calado (cut openwork) and suksok (supplementary

weft floats) became all the rage, as Garment of Honor, Garment of History details. The baro’s collar, previously lengthy to imitate the Elizabethan style of the 1700s, became shorter, lending a more elegant finish with fine pleats at the back and a distinct pechera.

Misconceptions abound when it comes to how the baro was worn. “The idea that the untucked baro was an imposition by the Spaniards is a relatively recent invention. As far as scholars know, there’s no actual proof that says that it was a policy of the colonial government,” Gonzales explains. “We think that it has always been untucked because that’s the way most Southeast Asians wear their upper garments. We don’t like things too close to the body, primarily because of the [hot] weather. People are even saying that it was transparent, because they [the Spaniards] didn’t want the Pinoys to hide weapons within the garments, which we think is also untrue.”

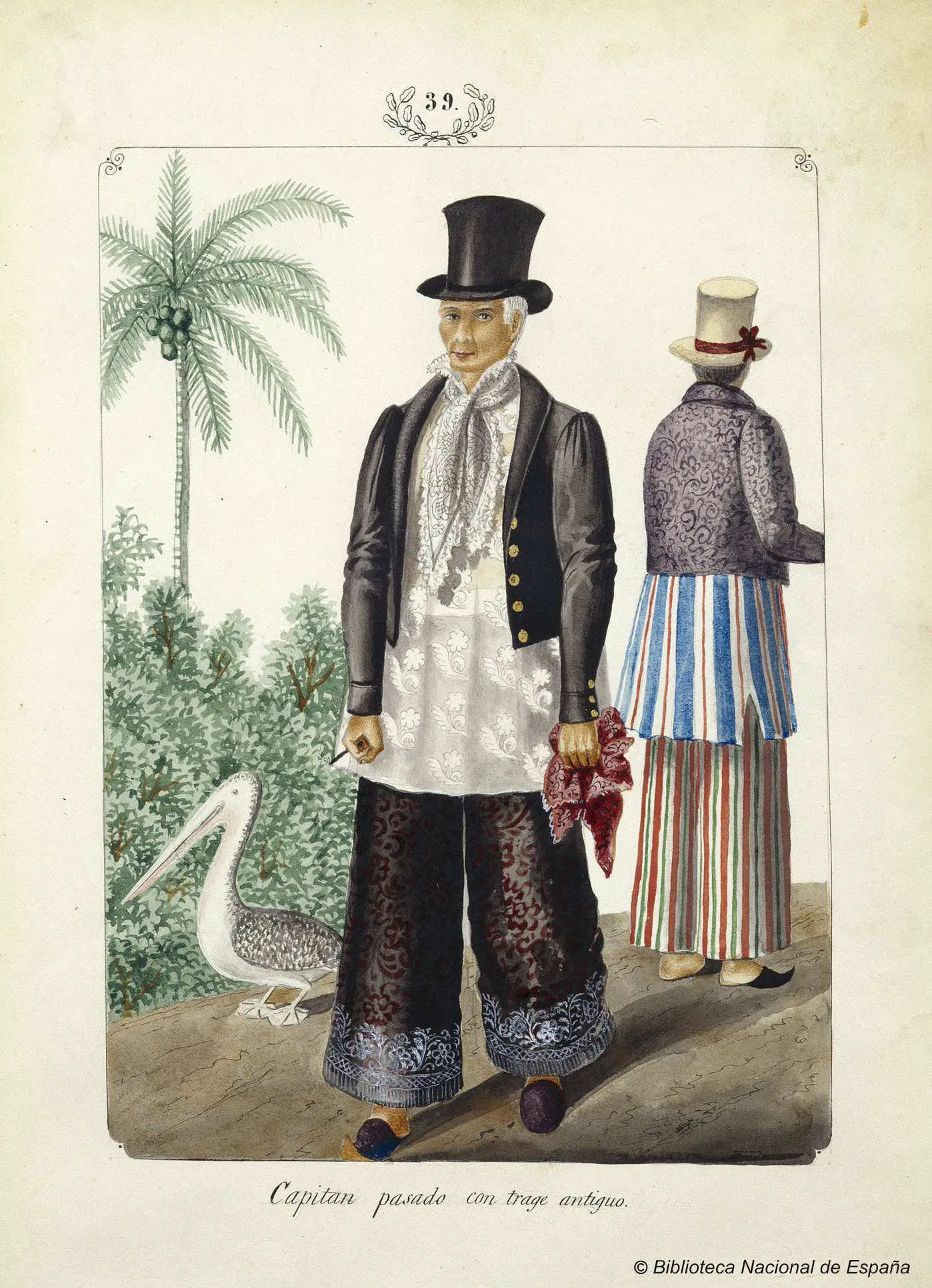

Fashion designer and writer Barge Ramos supports this theory in an essay on the barong from his book Pinoy Dressing: Weaving Culture Into Fashion. He explains that Spaniards likely encouraged Filipinos to wear the shirt untucked to distinguish themselves, writing: “Although the ilustrado [a wealthy, educated Filipino who could afford to travel and study in Europe] was allowed to imitate, to a reasonable degree, the Western manner of dressing, he was required to wear his shirt untucked, under the waist-length vest (chaquetilla) to categorically differentiate him from real Spaniards.”

The designer adds that while the garment is now a point of national pride, it actually used to be a symbol of oppression, “a harsh reminder that despite his wealth and social status, the ilustrado remained natives.” But these negative connotations wouldn’t last forever: public perception of the garment eventually changed through the fashion choices of the country’s future presidents.

The Rise Of A National Garment, Told Through The Style Of Philippine Presidents

Fashion historians, including Gonzales, mark the Commonwealth period—under then-president Manuel L. Quezon—as a significant turning point in the rise of the barong.

Before this era, the baro was known as “barong lalake de pechera” and “pecho montado” (references to its embroidered chest section). It wasn’t until the early years of the American period that it assumed

the popular name “barong Tagalog.” Today, scholars prefer to call it the “barong Filipino” or just “barong,” according to Gonzales, an attempt to acknowledge that the garment transcends Manila-centric narratives, having already been adapted by other ethnic groups as a national attire.

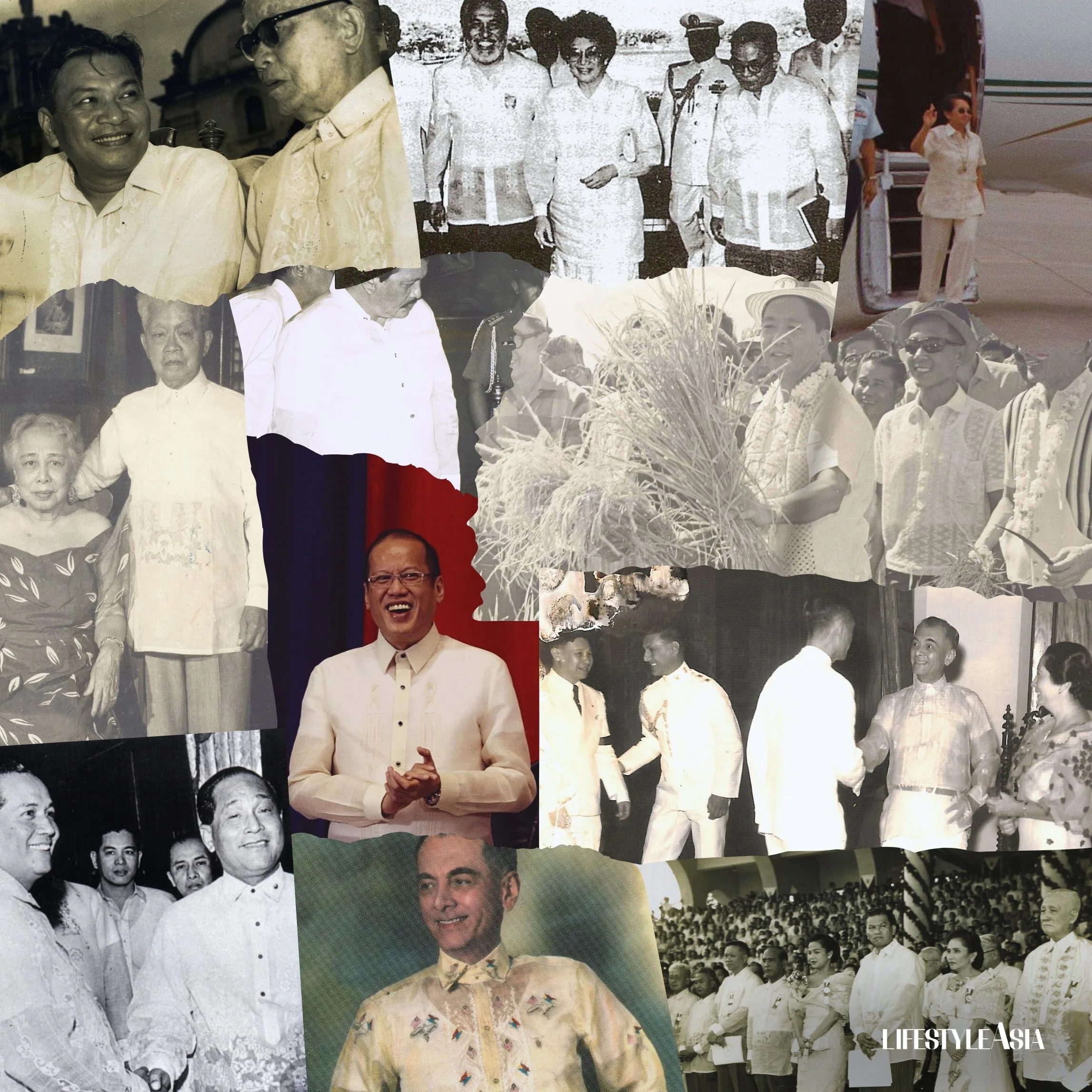

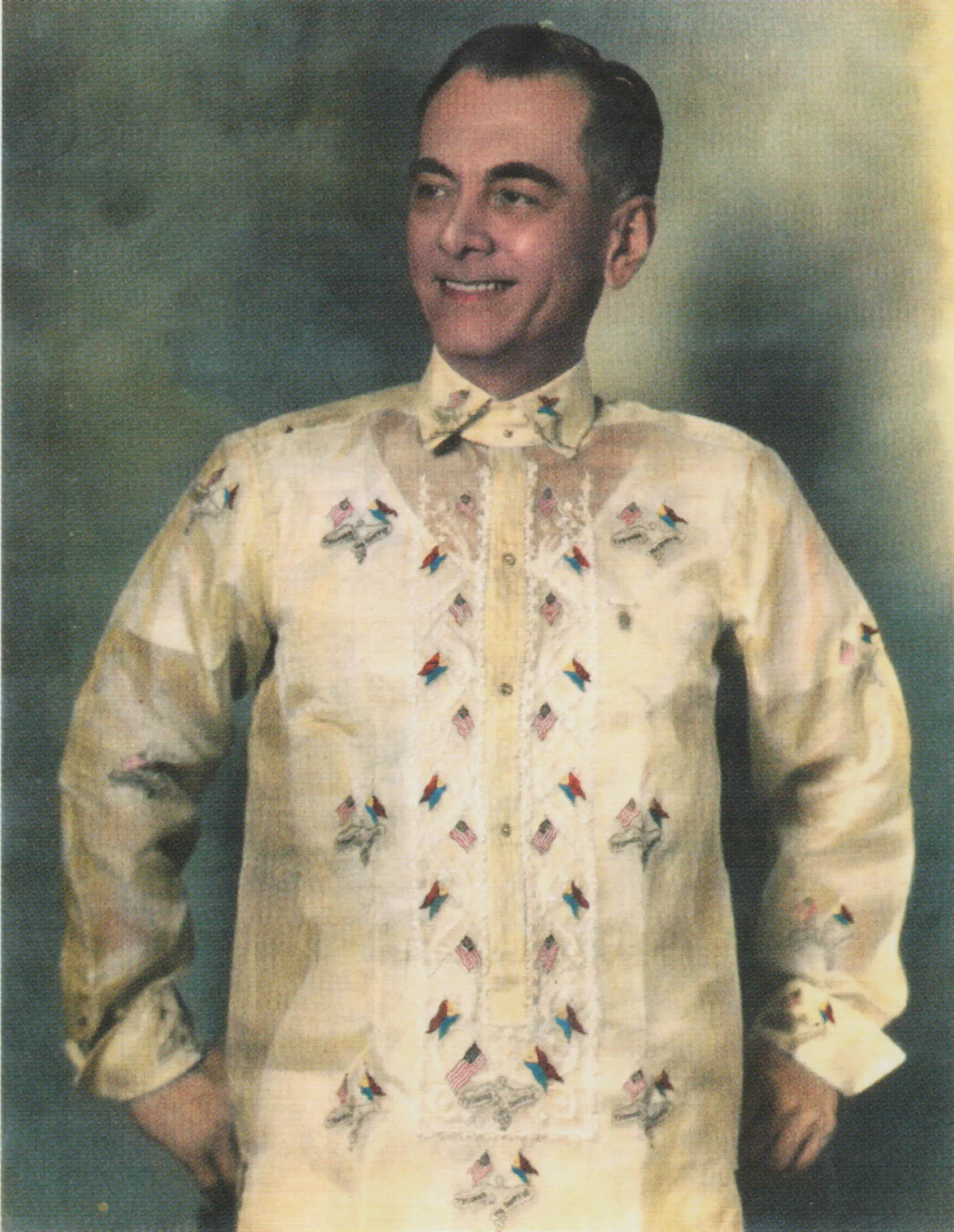

While Quezon wore a Western suit during his presidential inauguration—the common custom of the time—he made history by proudly wearing a barong after the ceremony. The iconic piece was called the “Commonwealth barong Tagalog,” characterized by unique embroidery that featured flags of the Philippines and the United States, as well as the scrolls containing the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which promised to grant full Philippine independence after a 10-year transition period.

“For me, the peak of Filipiniana was the Commonwealth period, for the barong and the terno [a type of Filipino dress made up of various components],” Gonzales shares. “I think that was the time we were trying to define ourselves as a nation, trying to prove ourselves worthy of being independent from the United States.”

“Filipinos needed to expunge residual reminders of Spain to fully define Philippine identity, this time in defiance of the Americans who swiped the nation’s hard-earned political independence,” adds Garment of Honor, Garment of History.

Being the president, Quezon’s choice created a ripple effect that began transforming the barong’s image. “If there’s a signal from the upper class that it’s chic or acceptable to wear this particular garment or use this particular object, normally it filters down,” Gonzales expounds.

Ramos’s Pinoy Dressing: Weaving Culture Into Fashion points out that under Quezon’s “Buy Filipino” program, embroidery designs also became more nationalistic, taking inspiration from the president’s iconic barong by featuring more Filipino motifs on their embroidery, like the sampaguita flower, palm trees, coffee beans, and nipa huts.

The Barong And Its Presidents

Perceptions of the barong only continued to improve from Quezon’s time as president. The next trailblazing president who redefined the garment was Ramon Magsaysay. Despite his short term, he did what no other Filipino leader had managed to accomplish: make the barong a staple.

“I think Magsaysay’s greatest contribution was making it mainstream,” Gonzales states. “Quezon still wore the Western suit in most of his formal affairs, while Magsaysay practically wore it every day.”

In 1953, Magsaysay was the first Philippine president to wear a barong during an inauguration. He’d continue to don it whenever he could, purposefully working to “dignify the Filipino image,”

described Garment of Honor, Garment of History. As these trends go, the public followed suit (literally), adopting the shirt as an acceptable and even fashionable option for business and formal occasions. In her book The Barong Tagalog: Then & Now, Visitacion R. de la Torre explains that floral and geometric designs also became popular during Magsaysay’s time.

Later presidents would follow: while Diosdado Macapagal didn’t wear the barong as religiously as Magsaysay, he donned it during special occasions, which is why he preferred his shirts with more flair or embroidery, not just on the pechera, but rather, the entirety of the garment. As such, Macapagal’s barong became a favorite design during big celebrations like weddings.

It was Ferdinand Marcos who officially made the barong Filipino the national attire in 1975. Like Magsaysay, he made it a point to wear the garment on most occasions, and in so doing, ushered in a wave of new and popular styles.

“At this time, the Pierre Cardin barong became popular,” Gonzales explains. “When Pierre Cardin opened in Manila, they started making barongs for President Marcos under [tailor and designer] Giovanni Sanna. When you look at the barong, you’ll notice it’s a very 1970s shirt—unlike the typical barong, which is very loose, this one skims the body. It has a wide, high, and pointed collar, as well as wide cuffs. It defines the waist, and it’s rather short compared to previous barongs; it follows the global fashion trend of the period.” The hidden buttons of these Pierre Cardin barongs extended beyond the chest (open all the way), a necessity given the more narrow nature of the pieces.

Marcos also popularized the polo-style or short-sleeved working barong. “He would often wear it to outdoor engagements during the day, such as ribbon cutting or tree planting; usually less formal affairs, which, as you can see, his son, [President Bongbong] Marcos Jr., picked up,” Gonzales adds. The current president also brought back his father’s more body-fitting barong style during his inauguration, partly under the influence of designer Pepito Albert.

Fidel Ramos, a former military officer, would roll up the sleeves of his barong—an unorthodox move at the time, but optically one that showcased the rugged, “hands-on” image he wanted to espouse as a leader. “Typically, the button near his neck would be unbuttoned, just to show that he’s relaxed and not uptight,” Gonzales expounds. “Actually, Rodrigo Duterte also took after Ramos, in the way he wore his barong. And during Ramos’s time, presidents were wearing santana—it’s a thicker, cheaper alternative to jusi and piña. So it’s saying, ‘We’re not ostentatious. We’re not wasting money, we’re practical’—I think that’s the subtext.”

Joseph “Erap” Estrada would also take a page out of Ramos’s style playbook, folding his barong’s long sleeves every once in a while, as de la Torre highlights in her book. Fashion historians note that Estrada had a taste for the finer things, often opting for custom barongs with fine embroidery.

“He would often commission Paul Cabral to do custom embroidery for his barongs—he loved bespoke things,” Gonzales recalls.

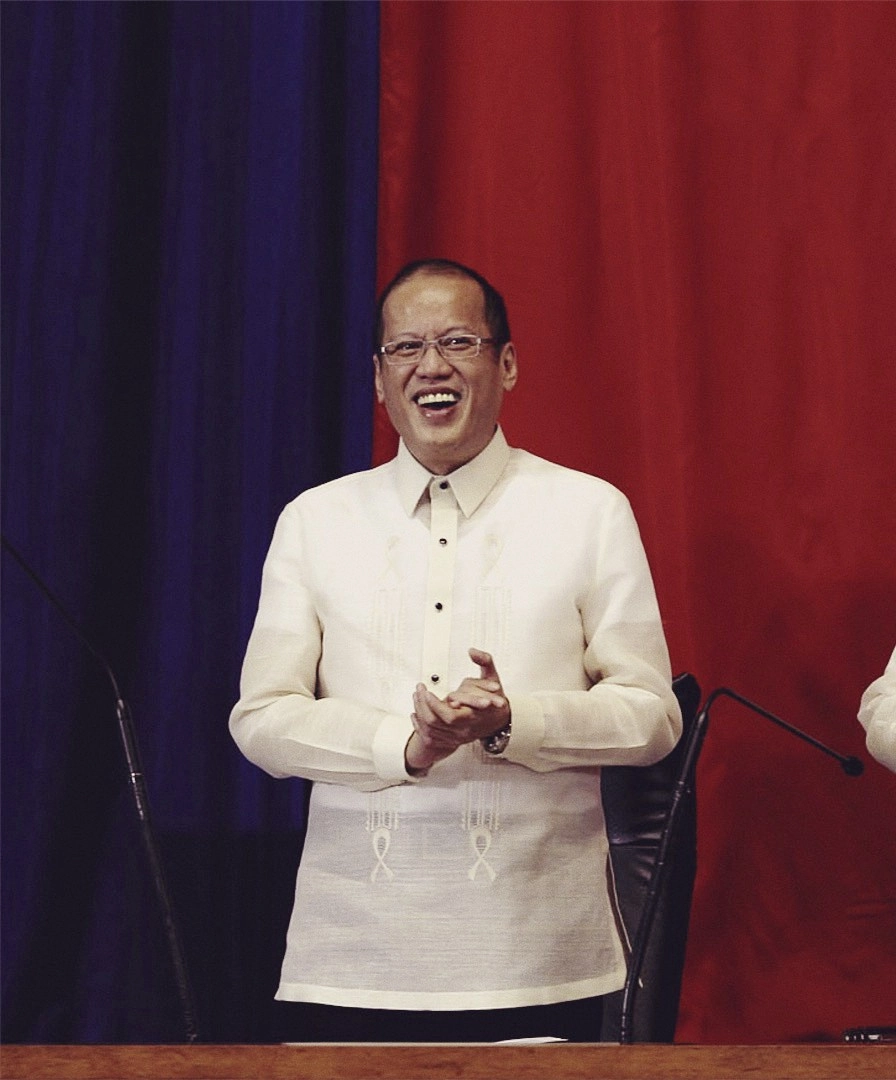

Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III opted for narrow, body-hugging barongs, perhaps to fit the more contemporary, sleek styles that were trending at the time, under the direction of his stylist Liz Uy. “He was a bachelor, so the communication was entirely different. The subtext was, at least for me: ‘I’m in tune with the times.’ His barongs were also relatively simple, in terms of embroidery, unlike previous presidents like Estrada or Marcos senior.”

Although the barong is often thought of as menswear, Filipino women have adopted the top with more feminine styling—the country’s only female presidents, Corazon “Cory” Aquino and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, being influential members of this practice. In fact, the “Cory barong” as people have penned it, still remains a popular style today, according to Garment of Honor, Garment of Identity.

“When Cory and Gloria wore the barong, that style filtered down to a lot of women,” Gonzales shares. “They both had a unique problem: they were always threatened by coup d’états—it’s a patriarchy,

right? So they had to show a certain toughness by way of dress. They didn’t always wear the terno, they would also shift to suits, paired with skirts or pants. There was a message in the way they dressed: ‘I’m not fussy, I mean business with you.’”

The country’s presidents exemplify the ways in which power ultimately shapes the fashion of an entire nation. Regardless of how one feels about these leaders, there’s no denying their influence. Yet the country’s people also have the freedom to decide on how the story ends, begins, and repeats. “Signals sent by leaders filter down the population, but sometimes the population rejects it altogether,” Gonzales elaborates. “When there’s a political upheaval, the fashions of the previous administration get rejected—or they get revived by a succeeding political dynasty.”

Why The Barong Filipino Endures

When asked why he thinks the barong has endured, Gonzales points out its versatility and universality, qualities that cut across social class, gender, age, and various situations. “What’s so successful about the barong is that we didn’t stop wearing it,” he explains. “It wasn’t confined as a men’s garment, and a lot of women took to wearing the barong as well, which is reflective of their rise in the workplace.”

Unlike the terno—which still hasn’t received recognition as a national attire—the barong also features fewer moving parts, making it much easier to wear. “The barong gives you more freedom than the Western suit and terno. It’s a cooler garment, whereas the terno can be cumbersome at times: it’s not something you can wear at every occasion. The barong is worn by everyone, from a company CEO to the security guard—and the lady guard. People wear it in the office or in the classroom if you’re a teacher. It takes a lot to get ready in a terno, whereas a barong is just something you pull over a t-shirt.”

The barong, as history shows us, is more than just a symbol of tradition and culture: it’s a living thing, a “barometer of the times,” as Gonzales puts it. Its story changes alongside Philippine society: once a part of colonial oppression, it now enjoys the status of the multi-faceted and respected national garment because its people reclaimed it. It’s a story centuries in the making, and it continues to be told.

This article originally appeared in our June 2025 issue.

Photos courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de España, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, The Presidential Museum and Library Flickr (2010-2016), and Gino Gonzales