As we celebrate the birthday of national hero José Rizal, we remember his legacy as a man whose narratives inspired a nation’s fight for freedom—his descendants are carrying on the tradition, ready to tell his stories to new audiences.

The story of José Rizal doesn’t end in death, by the sound of a gunshot. It survives him—not just because he’s a national hero whose deeds have become required teaching material, but also because his family lives on, remembering him in their own ways. While Rizal only had one child, a stillborn son with his common-law wife Josephine Bracken, his siblings went on to start their own families, each branch preserving parts of their ancestor’s story and passing them on. Two of Rizal’s descendants, Maxine “Max” Cruz and Patrick Filart, sat down with Lifestyle Asia to reflect on their family, what Rizal meant to them, and how they’re carrying on his legacy of impactful storytelling for a new audience.

READ ALSO: The Power Of Style: A Story Of The Barong Filipino’s Evolution

Max Cruz

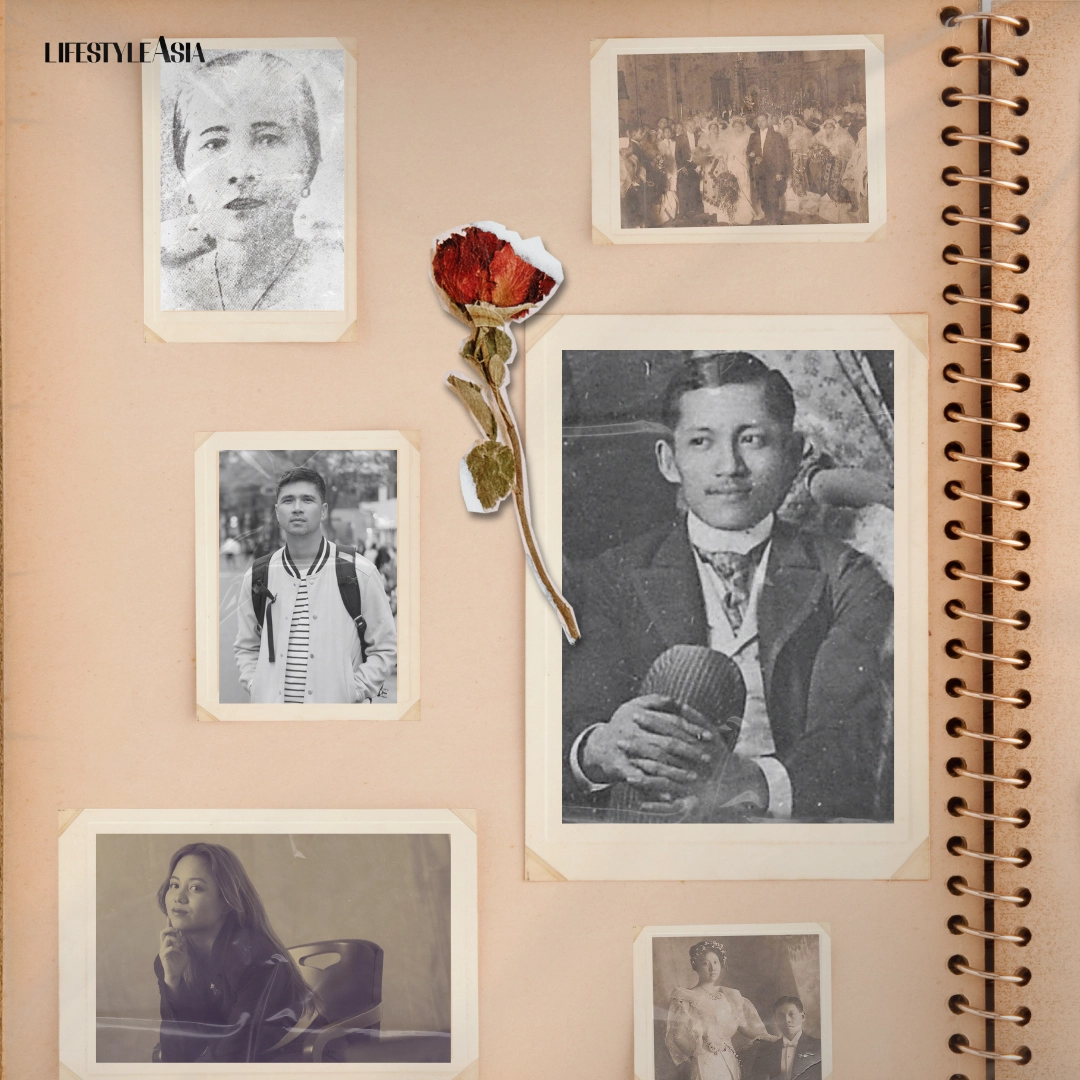

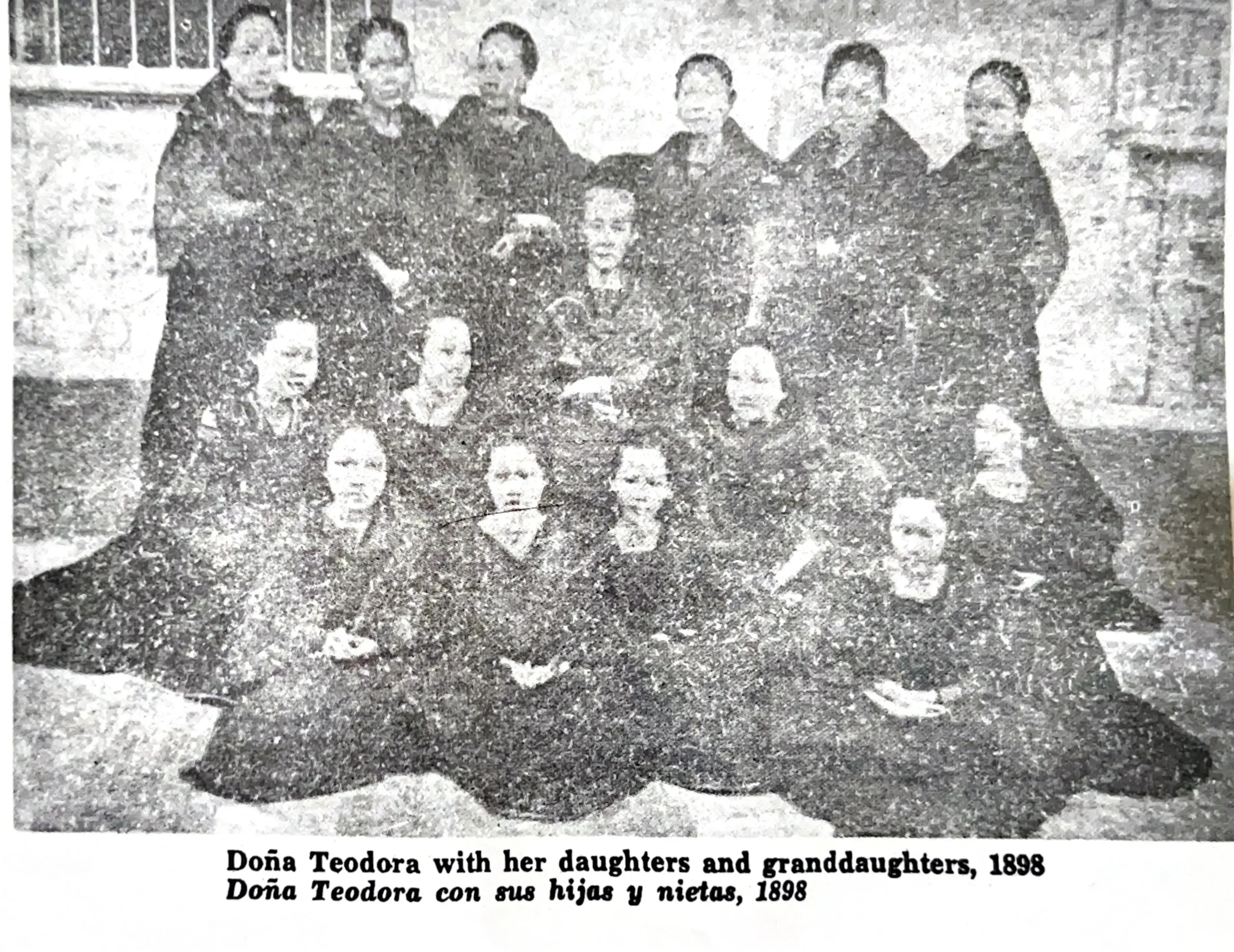

Rizal, like many Filipinos at the time, was part of a big clan. His father Francisco Mercado and mother Teodora Alonso had 11 children, Rizal being one of two boys (the other his older brother, Paciano). The rest of his siblings were girls, and included Maria Rizal, who was born just two years before him. Maria would go on to marry a man by the name of Daniel Cruz: their son Mauricio Cruz had a daughter, Fe Cruz, and she went on to have a daughter, Barbara Gonzalez—Max’s grandmother.

In her 20s, Max is a long way down the line from Rizal, but his presence was an inextricable part of her school life (as it was for many of us). Recalling her earliest memory of learning about him, she shares: “I didn’t know he was family yet, until I got home from school one day and my dad told me. Shortly after that, I was given his storybook, The Monkey and the Turtle, and read it at a pretty young age.”

Rizal’s legacy would only continue to become a prominent part of her life, as she remembers attending an event for his 150th birthday in grade school. “We were invited to Calamba [Laguna, Rizal’s birthplace]. We went to his Calamba house, what you’d visit in a grade school field trip; but I was super amazed because I got to see it in a different light, since they allowed us into places they didn’t usually allow other people to go to. I thought it was really fun, and after the celebration we moved to Fort Santiago [for a family reunion] and watched re-enactments. That’s when I became even more aware about our relationship with Rizal.”

“The more I learned about him throughout grade school and high school, the more I could appreciate the man I’m related to,” she expresses. Rizal is almost, to some extent, a legendary figure in Philippine culture; which is why it’s easy to understand why Max carries a deep sense of responsibility in regard to her lineage. She worked hard to do well in history class, and when family began tapping on her to talk about Rizal during important functions, she took it upon herself to learn everything she could. “Everything I have to say has to be correct, fact-checked 1000 times,” she explains. “I’m not in a position where I can afford to be wrong.”

The Man Behind The Title Of National Hero

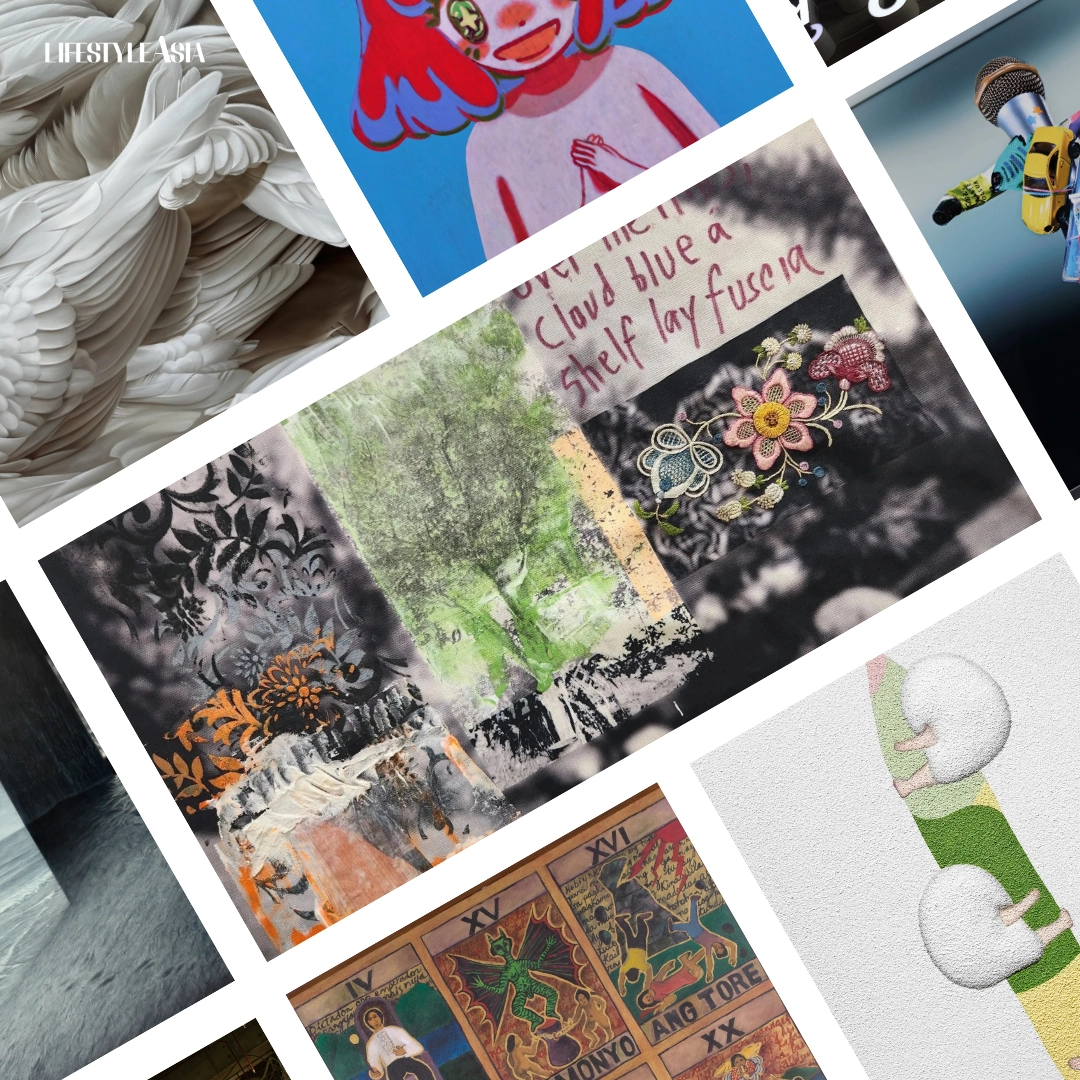

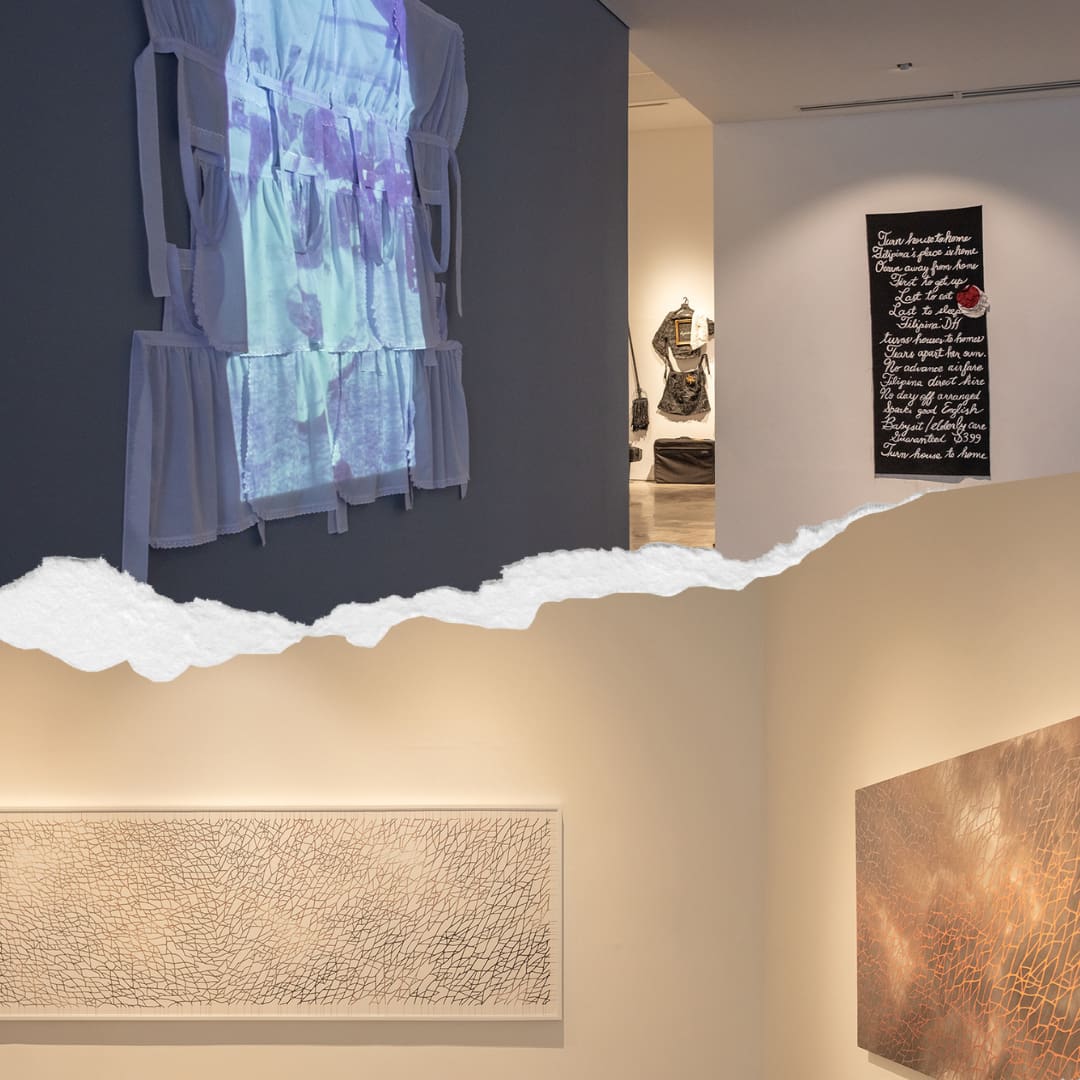

It’s easy to forget that, at the end of the day, Rizal was a man with hopes, follies, loves, and doubts. As a content creator on social media, Max has been steadily building a platform to help a new generation of audiences better understand the national hero beyond his title.

“I also feel like I have the responsibility of making sure that he’s humanized, because the way we learn about him in school is very bullet points: he had the highest grades, great, he was like this or like that. I studied Rizal so much, I got to see a different side of him: how he was funny, sarcastic, a shiftee in college,” she shares. “He’s not this super textbook perfect person that we were made to believe he is. He had his flaws and still became a hero despite that. So for me, that was very inspiring, because if the national hero was someone who entered college not quite knowing what he would do, who only passed certain subjects [Max later adds that the word aprobado, loosely translated to “passing grade,” was the term used to describe this academic performance]. I think we can all make something of ourselves as well.”

I ask if there are any particular anecdotes about Rizal that family passed on, and Max mentions a funny yet eerily prophetic one. “His siblings were all making fun of him because he carved a little statue of himself, and they were saying ‘Oh it’s so ugly!’” she begins (clearly, sibling behavior hasn’t changed over the past centuries). “But then he says, ‘All of you are making fun of me now, but one day after I die, people will be raising statues of me.’” True enough, that’s exactly what happened.

Being two years apart, Rizal also shared a close friendship with his sister Maria. “When he was studying in Spain, he found out Maria eloped through a letter from Paciano,” Max shares. “He was devastated, and he felt bad because she didn’t tell him, even if they were close.” Maria herself was a vibrant, headstrong, and independent young woman. Her marriage to Daniel Cruz didn’t work out, as Max’s grandmother Barbara told her. “He [Daniel] had everything going on for him: he was very good looking and cooked very well, but he was a cheater and gambler,” she continues. “So one day, very dramatically, she left money on the table and told him, ‘If you take this and gamble it, you will never see me and your children again.’ He took the money, so she packed up and left.”

Maria had to fend for herself and care for her children while living with one of her sisters in Binondo. Thankfully, she was enterprising enough to run multiple businesses, including a warehouse, farm, and at one point, even a boxing studio. All of this earned her enough money to support her family. Daniel even returned to her one day, wanting to rekindle their relationship—and while she did take him in, she never spoke directly to him again, instead asking house help to deliver her messages.

“So you know, they’re people too,” Max says with an amused laugh. “I think that story of hers, needing to pick herself back up after her marriage didn’t work, is super important. Because even if you’re the family of a national hero, things like this still happen, and problems like this still arise.”

Sharing History On A New Platform

Max didn’t exactly plan to start a social media platform focused on history—but who does? That’s how these things go: they just naturally fall into place, one series of choices leads to another, and suddenly you’re where you are.

As a radio host in college, she was already growing a following of her own. During the lull of the pandemic, she decided to create videos, inspired by the TikTok boom and surge of online content—though the topics were eclectic. “It was all pretty spread out, I was still figuring out what I was doing. I would post interviews, snippets of what I ate,” she shares. It was one fateful car ride with her grandmother Barbara, towards the tail-end of the pandemic, that changed the trajectory of her passion project.

“We were invited to the National Library to view the presidential exhibit, see Rizal’s original manuscripts and papers. I had just graduated, and we were talking about all the possibilities waiting for me,” she says. “She was a writer, and so she asked what kind of medium the youth use nowadays. We talked about social media, how difficult it is to stand out. She told me being a descendant of Rizal gave me a unique perspective that not a lot of people had, so that was the turning point for me.”

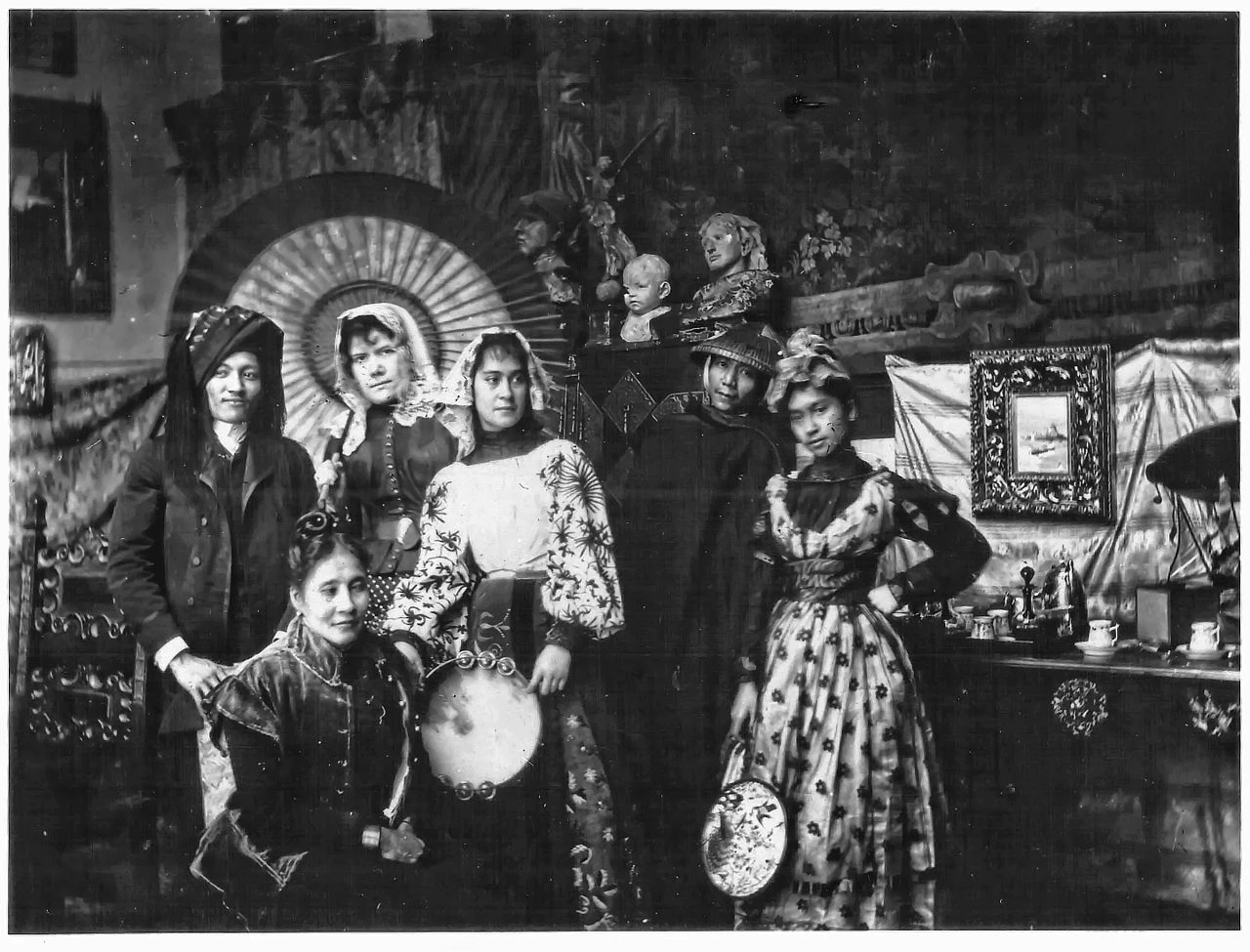

One day, Barbara visits Max at home and drops off a big box. It’s filled to the brim with all kinds of documents, books, diary entries, and archival photographs about Rizal and their family: the equivalent of passing on the torch, so to speak. Encouraged by family—and a social media talent agency who later picked her up—Max turned her interest in history into an engaging array of short-form videos for a new generation. “Now I don’t just talk about Rizal, but also other figures in Philippine history; and I notice audiences really like watching videos about food history as well,” she shares.

The observation is spot on: one of the most popular videos on her Instagram (@hannahmaxinecruz) is an intriguing piece about how Filipinos helped invent tequila through the galleon trade. Though her reels offering glimpses of Rizal’s life outside history textbooks are just as interesting, ranging from the hero’s homemade board games, art pieces (including one of his final sculptures, a touching piece depicting Josephine Bracken), and more famously (because people love a good romantic drama) the inner world of his dalliances with several women. At present, Max is working on a history podcast under PaperbugTV, excited to talk more about Rizal and other historical figures.

She recently finished recording one episode where she interviews one of her grandaunts, Gemma Cruz-Araneta (like Barbara, another writer and descendant of Rizal most famously known for being the country’s former secretary of tourism, as well as the first Asian and Filipino to win Miss International in 1964). Looking back, she realizes how important it is to frame history like a conversation—one person telling you what happened or “spilling the tea,” as she describes in true Gen Z fashion, offering their own perspective on certain events.

“It’s like you’re listening to a friend tell you a story about someone you know. That’s a really nice way to learn about history, because it makes it less intimidating and you kind of retain more. It just feels more human,” she elaborates. The upcoming podcast episode will also be subversive in its chronology of events, working its way backwards from Rizal’s death to his birth. In a time when misinformation can be found everywhere, Max’s job of setting things straight—as both a lover of history and descendant of the national hero—is more important than ever.

“I hear stories from people who heard it from somebody who was actually there. Some historians whose books I read in and out of school are now my friends. We have access to Rizal’s books, documents, diaries,” she explains. “I cite my sources and state whether information was from a family member. I make sure to fact check hundreds of times. I don’t trust just any website, and I look for scholarly articles too—at least two or three that would support a claim. If I see something in a museum, better.”

Of course, the internet will always be the internet. Even with Max’s layers of fact-checking, there will be contrarians who refuse to be swayed despite the evidence. That said, history in itself is ever-changing as more information is uncovered over the years, a fact Max acknowledges wholeheartedly. “New evidence could show up one day and disprove what you say, and you just have to be open to that, because it doesn’t make you 100% wrong. That’s the research that was provided at the time. That’s what everybody knew; but now, here’s this new evidence. So yeah, these things do change.”

Why Remember The Past?

Carrying the values of her forefather, Max is a staunch believer in the importance of learning history, especially when it comes to forming a national consciousness and fostering a sense of civic duty. “You really need it, not just the names and dates, but the whys and hows. Rizal was the type of leader who wanted to empower other leaders. His goal, when he was a teacher, was to raise students who would one day be better than him,” she shares.

Like a knowledgeable and friendly classmate, Max aims to educate in her own way, without any condescension. “When people watch my content, I hope that they feel smarter after 30 seconds of me telling them about something they might not know,” she expounds. “I don’t have that big of a following, but it reaches the right people. All of them tell me they appreciate how easy it is to understand [my content], because it’s like I’m just making kwento [storytelling]. My goal is not to school you and be like, ‘Yeah, I know it all, learn from me.’ No, it’s saying, ‘Did you know this?’ so they could be like, ‘Oh, now I do know.’”

Similar to Rizal, Max’s goal is less about making a name for herself, and more about connecting with other people and sparking positive change. “He didn’t want to be the greatest figure in history, he wanted to help make the greatest figures in history. He really opens the conversation, he asks ‘What can we do to make things better?’” she shares. “I hope this inspires somebody to speak their mind and contribute to the country in ways that they want to.”

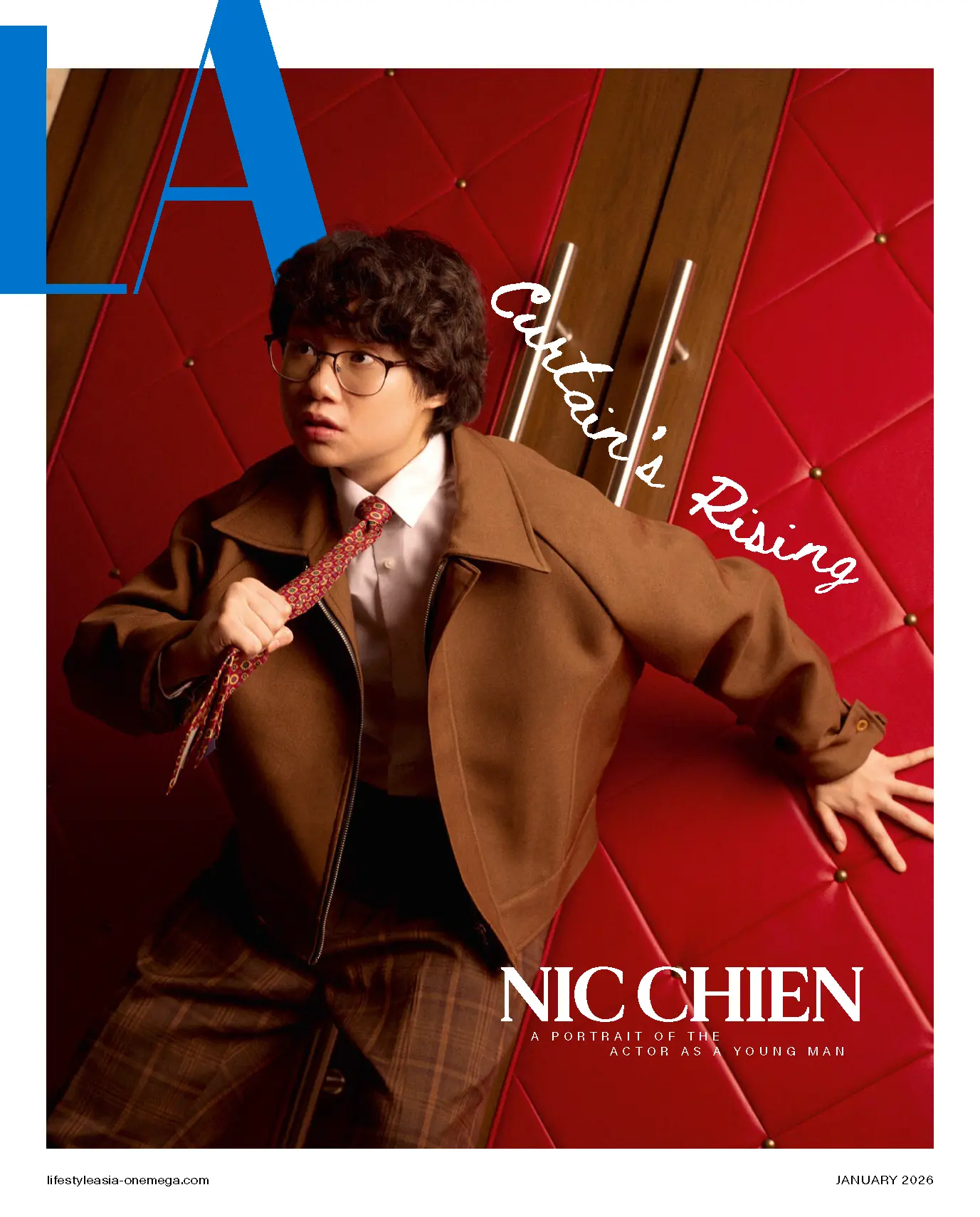

Patrick Filart

Older than Max, but still one of the younger descendants of Rizal, is Patrick. Rizal’s sister Olympia (his senior by six years) only had one child with her husband Sylvestre Ubaldo, as she passed away shortly after giving birth to her son Dr. Aristeo Rizal Ubaldo; he’d go on to marry and have a daughter, Pacita Ubaldo, and her son Alberto Filart is Patrick’s father—making him Rizal’s great-great-grandnephew.

With a family of his own, Patrick has also assumed a career in media, running production company Thirtysix-O, as well as film and broadcast equipment distribution company Voozu. He shares a slightly different relationship with his forefather compared to Max, having spent most of his younger years not knowing much about him. The standard, rote memorization method of teaching history didn’t help foster a deeper appreciation for the hero either. Things changed when he took up a class dedicated to Rizal in college: his professor shifted the way history was taught by finally showing glimpses of the man behind the name.

“He gave us letters that Rizal would write to his friends, his family, and priests. Then he would compare and contrast, juxtaposing it to his actual writing in El Filibusterismo and Noli Me Tangre,” Patrick elaborates. “Then we understood why he wrote this character a certain way, why this character said this; because in real life, this is what he actually believed in. So you kind of get a sense of who he really was. This gave me a deeper appreciation of him.”

Rizal The Uncle

Since Olympia died from childbirth complications, her son Aristeo—and by extension his descendants—never got a chance to truly know her. What Patrick does know, based on a few of her letters that remain, is that she was supportive of Rizal’s ideas, writing back to him and delivering his messages to the family.

As for Rizal himself, Patrick paints a portrait of a caring uncle who not only watched over his nephews and nieces, but also served as an inspiration to them. “Aristeo would go on summer breaks to Dapitan, since Rizal often invited his nephews for visits. Those were the times he would tutor or mentor them,” he shares. “I think that was one of the main reasons why Aristeo became a doctor, because of those summers with his uncle.”

His Life In Film

Patrick cites the Second EDSA Revolution in 2001 as a catalyst for his work in media. “I was taking computer science, but I had no idea what I wanted to do in life. During EDSA Dos [the Second EDSA Revolution], I saw how powerful and influential the media is. I had no background in directing, editing, or producing shows, but I wanted to see how to get there; see what it would be like if someone used this influence and power for good,” he expresses. “Disseminating proper information, educating, challenging world views, encouraging people to hope and dream—I didn’t know what that was going to look like, but everything from then on was a small step towards that direction.”

This epiphany led him to establish his two companies, with Voozu distributing broadcast and media equipment, and Thirtysix-O being creating content like online ads, TV commercials, corporate videos, and event coverages for a wide range of clients. “We go where the company can survive,” as Patrick tells me, and these efforts will hopefully allow him and his team to venture into even more creative avenues of storytelling.

“Right now, we are in the early stages of exploring projects related to Rizal and his ideas, maybe through film or an animated series. I’m hoping I can use my network and the resources from being in the industry since 2010,” he shares. “We’ve started discussions as well with the Rizal family and its leadership, and they’re all interested. They’re all on board. So it’s just really a matter of taking it step by step.”

With all his experience, Patrick can confidently say this: there’s a wealth of talent in the industry. And like his forefather, he believes there’s plenty of good to be done through art.

“Most of these talents—the directors, art directors, cinematographers, writers, producers—didn’t really grow up saying, ‘Oh, I want to be a director because I want to create an ad!’ It’s ‘I want to be a director, because I want to make a film.’ They’re all kind of just waiting for that opportunity to do it,” he states candidly. “For me, it’s about having a network of these talents and saying, ‘Hey, if we get an opportunity, let’s use what we’ve learned. Let’s use our experience. Let’s use our creativity and create something educational, informative, and also super entertaining.’”

Rizal Today

Reflecting on what younger generations can take from Rizal, Patrick says this: “He was always learning, always trying to improve. His perspective of the world was that it could change or get better. But on the other hand, he had principles and ideals that he stood for, even died for. He was never going to back down on them. That’s something we can learn from.”

He echoes a sentiment Max shared, about what it means to be a “hero”—because more often than not, it’s never an item on a checklist or a title to win. “He wasn’t learning or accumulating all this knowledge to get rich. He wasn’t doing it to get power. He was doing it so he could help find a way for the Philippines to move towards a better future,” Patrick expresses.

Unanswered Questions

It’s fitting that two of Rizal’s descendants are so closely tied to today’s media landscape. It makes you wonder what the hero would’ve been, if he’d been born in their respective generations. Max thinks he would’ve made a great travel vlogger, being the meticulous writer and adventurous person that he was. For all we know, he might’ve run his own production company like Patrick; opened a publishing house; created informative video essays on history, art, and all things under the sun for his YouTube channel.

“I feel like he’d be so curious about the globalization of K-pop or he’d want to get to the bottom of A.I. Of course I can’t speak on his behalf, but based on who he was, I just have a feeling he’d be into these things,” Max says with a smile. “He was very interested in learning about different cultures, and finding out why things become trends. I’d like to know his thoughts on all these.”

Coincidentally, Max and Patrick give a nearly identical answer when I ask them what they’d say to Rizal now, if they could speak to him. Their responses crystallize into a question, rather than a statement: How do you feel now, looking at everything you’ve done?

“Was it worth it?” Max asks, before pausing. “He knew that he would get killed one day, for what he was saying. But it didn’t stop him. I’d want to know, if he could watch everything that unfolded after his death, would he have thought that the sacrifice was worth it?”

“I don’t think he’d feel regret, knowing how he wrote or saw things. But I wonder how he’d feel, after all his efforts,” Patrick shares. “The things that he fought for and stood for, and wanted the Filipinos in that generation to learn—I think we still need to learn them today, and we still haven’t really gotten it yet. What are the things he felt he could’ve done differently?”

These questions remain unanswered, and maybe that’s for the better. Rizal’s work is finished, but his legacy isn’t. It’s time to turn to the next page, and hopefully his descendants—and this new generation of Filipinos—will write a tale they can be proud of.

Photos courtesy of Max Cruz and Patrick Filart (unless specified).