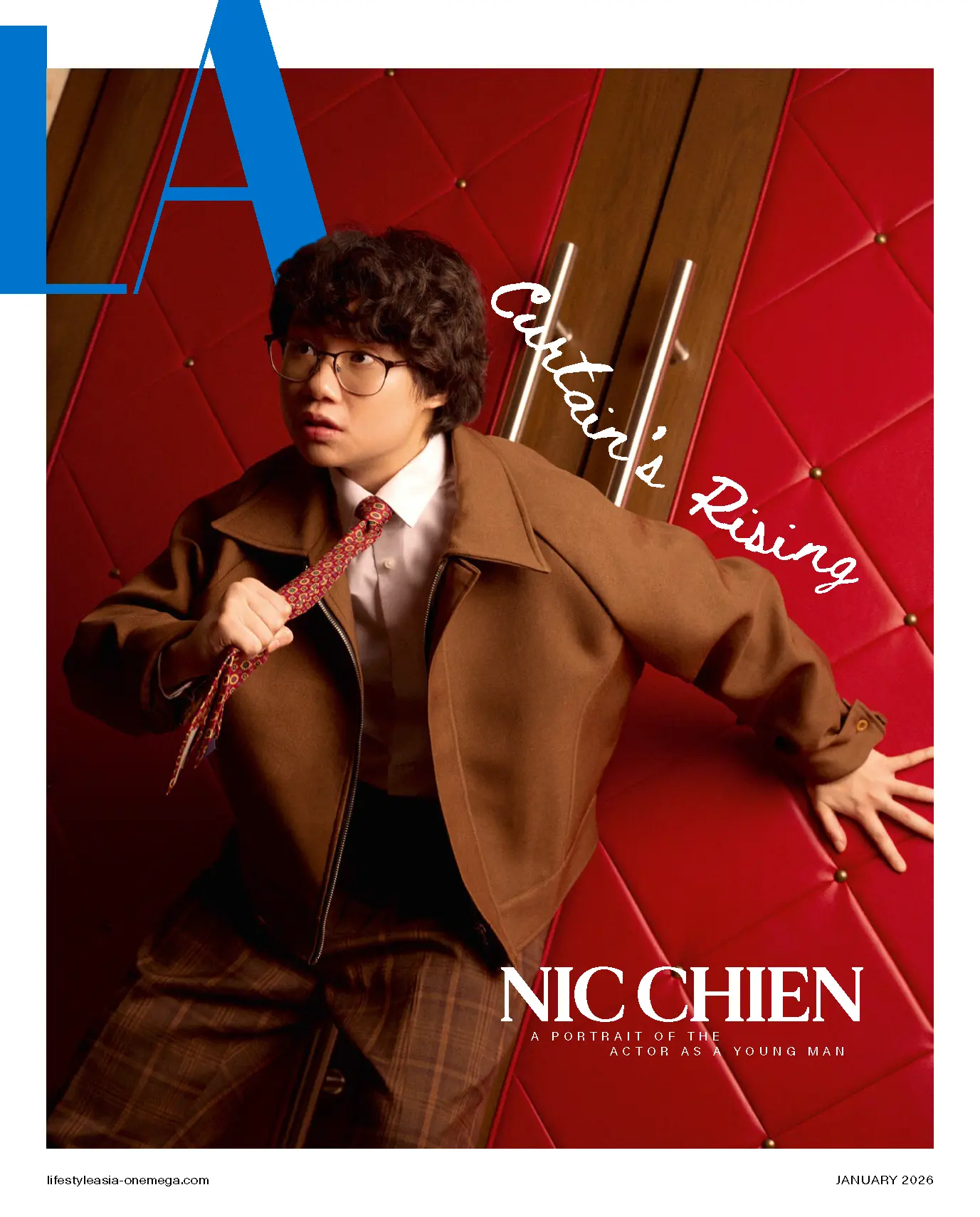

Celine Song’s sophomore film tries to say something profound about the state of dating and the nature of romance, but it fails to stick the landing.

Warning: This piece discusses key themes and character dynamics in Materialists, with light references to the film’s structure and romantic setup, but no major plot reveals.

When I saw the caveman and cavewoman, I had to double-check whether I’d entered the right theater. I was a few seconds late and caught off guard—this was Celine Song’s Materialists, right? I didn’t get the answer to my question until the scene transitioned to the bustling streets of New York.

So yes, I was in the right theater, and yes, the cave people somehow matter. Or at least, the movie clearly wants them to matter (there are not one but two scenes with our Neanderthal lovers), since the main character references them in a late attempt at posing a philosophical query about romance.

It’s perplexing, but not nearly as frustrating as what follows over the next two hours: a story that wants to critique our modern ideas of dating but ultimately doesn’t earn its arguments. It felt like listening to someone who never follows their own advice: love is this, love is that, but where is the love you’re talking about? Everyone looks like they walked out of a perfume ad, but no one’s actually in love—at least, it never feels that way.

As far as romantic dramas go, this is concerning. Granted, I came in expecting this wouldn’t be your typical 2000s romcom. International reviews that preceded the film’s Philippine premiere gave me enough warnings about the misleading trailer. I thought, sure, then show me something different. If you’re not going to lean into romance, dig deep into the cold, gaping hole of consumerism; show us the ugliness. The film does touch on that ugliness, but its biggest mistake is contrasting it with a romance so flat, it undercuts the very point it’s trying to make.

In other words, whoa, valid points! But also, whoa, terrible examples!

READ ALSO: The Challengers Effect: How One Sexy Tennis Movie Became A Cultural Obsession

Materialists Has Ideas—But No Follow-Through

I don’t intend to turn this into a hate post because, believe me when I say this, I wanted the movie to succeed so badly. Even with the plummeting Letterboxd stars and divisive reviews, I still went out of my way to catch it after work. Alas, the disappointment I felt while walking out of the theater was actually the strongest emotion the movie elicited…which is depressing.

I adore Past Lives—it’s a strong directorial debut. It didn’t leave me shaking or crying (that award goes to Aftersun), but it did make my chest ache. It had me thinking and feeling long after the credits, which is something I look for in a film. After watching Materialists, I’ve gained a better understanding of why its older sister succeeded.

Both works are personal (Past Lives more so) and loosely based on Song’s own experiences. In the case of Materialists, the filmmaker shared that she once worked as a professional matchmaker in New York for roughly half a year during her 20s, much like the movie’s main character Lucy (Dakota Johnson). This inner world of not-so-romantic calculations is, to my mind, the strongest part of the film.

Johnson’s deadpan voice and cool demeanor helped her pull off the somewhat jaded, conventionally attractive, calculating matchmaker role. She makes some interesting points that hold weight on their own. She mirrors Song’s insights: dating has become a numbers game. Height, weight, age, salary. Never mind that someone’s a real catch—they’re four inches shorter than what you envisioned the love of your life to be.

In this shallow world, it’s difficult to see the essence of a person, which can actually lead to dire consequences. The film takes a darker turn somewhere in the middle to illustrate this; it’s a little off-kilter, but it does present a thought-provoking ethical dilemma before losing the thread completely with a lackluster conclusion.

I think the parts that struck me most were the ones centered on Lucy’s career and personhood: how she simultaneously understands the inherent, glorious messiness of human relationships yet chooses to be a “love mathematician” who treats romance like a commodity or clean-cut transaction. This push and pull is what kept my eyes on the screen. Sadly, everything else fell short.

What I appreciate about Past Lives is how it never really forces audiences to view the complex relationships of its three characters in a particular light. It leaves just enough space—just enough trust in the viewer’s emotional intelligence—for meaningful contemplation and maximum impact. The pointedness of Materialists, on the other hand, turns eye-rollingly didactic: from drawn-out monologues to stilted dialogue, it often feels like someone’s shoving ideas down my throat, rather than taking the time to explore them through more nuanced character interactions.

The film is trying to say that real love is nonsensical, inexplicable, and oftentimes impractical. This statement is grounded in truth (hell, I wrote an entire article about online dating with a similar thesis), but Materialists doesn’t do a great job of getting the audience to really believe it. There has to be a method to the madness. As illogical as love is, the dynamics between characters have to be strong enough to suspend disbelief, to get the viewer invested in what’s at stake. Yet I really can’t bring myself to actually care about any of these people, let alone their relationships with one another, because I don’t understand what they mean to each other.

Broke Boy Propaganda, Messy Writing, Tepid Chemistry, Or All Of The Above?

Early reviews of Materialists accused it of being “Broke Boy Propaganda.” You know what that is, you’ve seen it countless times. When presented with two options—usually a financially stable (sometimes boring) “nice guy” and a brooding, broke, yet passionate “just some guy”—a protagonist will likely gravitate towards the penniless man because “Mother, I love him, money isn’t everything!”

This cliché seems to be the unironic, beating heart of Song’s film. Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. We get it: the world cares too much about money, capitalism is making us forget our most human needs. Wealth isn’t emotional fulfillment. Harry (Pedro Pascal), the private equity millionaire with a giant sexy penthouse, won’t listen to you crash out the way John (Chris Evans), your financially-burdened, struggling actor ex-boyfriend does. Sure, said ex says all the wrong things and has a terrible temper, but he reallllyyy loves you with all his heart.

Can I be honest? I couldn’t help but root for the millionaire. Though Harry isn’t all that compelling, there are glimmers of tender vulnerability in his dynamic with Lucy that still outshine her relationship with John. Plus, who wouldn’t find themselves attracted to someone who pays for fancy restaurant dates without batting an eyelash?

Maybe my gut response is the very reason why Song created this film. (Gasp! Am I the problem?) Defenders of Materialists will argue that our disappointment in the movie’s themes is the point. The filmmaker is asking us to reevaluate the material priorities of our own relationships. I get her sentiments, I really do. Love is seldom practical. It doesn’t think in numbers. Feelings creep up on you. You’re wise and pragmatic until you actually experience the irrationality of attraction yourself.

But saying the movie is one giant social experiment feels like an excuse to cover up sloppy writing and a lack of chemistry. Pascal doesn’t get to shine much: Harry is quickly reduced to the stereotype and plot device I dreaded, but expected (there’s some depth but it’s never expanded on). Evans’s John is the script’s emotional centerpiece, but the writing never allows him to be charming. His relationship with Lucy doesn’t feel like love. It feels like a badly paced, predetermined conclusion. Nothing about them screams compatibility. In more than a few parts, I was left scratching my head and thinking, “Seriously? Girl, are you sure?!?”

It’s not because John is unattractive. It’s not because his New York accent is kinda ridiculous. It’s not because I detest the broke man stereotype (not a fan, but if you give me a well-written character, I’ll make an exception). It’s because I really don’t understand what he has to offer, even as someone who considers herself a romantic. It’s like being excluded from an inside joke, but still expected to laugh.

The movie is so fixated on the wondrous mystery of love that it forgets something crucial: it’s still a story that needs not-so-wonderous structure to build on its points. There are brushstrokes of intimacy, but not enough to complete the picture. These small acts of love and sacrifice might’ve been appealing in a tighter, more fleshed-out script, but as it stands, they just land awkwardly (with about as much grace as a baby elephant falling on its tush).

The film’s Japanese Breakfast song “My Baby (Got Nothing At All)” pretty much sums it up, but not in the sweet way it intended to. Yeah, he’s got nothing at all—and he doesn’t just give it to her, he gives it to all of us. Now we’re left deciding what to make of that great big nothing.

Oh, but it does return to the cave people. And somehow, those two prehistoric partners—wordless as they are—were more convincing than any pair in the main story. It’s a strange thing to take away from a film about modern love…feeling most moved by two people who don’t even speak or live in the same timeline as us.

Photos courtesy of IMDb.