National Heroes Day honors the deeds of the country’s influential figures; yet, surprisingly, none of them are officially recognized as heroes.

Thinking of what to write in honor of National Heroes Day, I was taken aback when I discovered that none of our heroes are formally recognized—be it through law, executive order, or proclamation. Don’t believe me? Well, I could hardly believe it myself (I always assumed this was written somewhere), but the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) wrote about it in detail.

Even Jose Rizal—an integral part of our country’s historical DNA—has never been proclaimed a national hero on paper. The same goes for Andres Bonifacio, whose birthday on November 20 is considered another national holiday.

READ ALSO: José Rizal’s Descendants On Keeping His Stories Alive For The Next Generation

The Initial Criteria For National Hero

While no heroes are officially recognized, there was an initial attempt back in 1993 when then-president Fidel V. Ramos established a National Heroes Committee to evaluate and create a list of heroes for their contributions to the country.

The committee held a series of meetings over two years to discuss and deliberate, creating the criteria we have today. Members of the group included notable historians and academics, such as Serafin D. Quiason, Ambeth Ocampo, and Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil.

What they produced were three main factors to consider when choosing who’d be called a national hero, essentially:

- Heroes are those who have a concept of the nation and thereafter aspire and struggle for the nation’s freedom.

- Heroes are those who define and contribute to a system or life of freedom and order for a nation.

- Heroes are those who contribute to the quality of life and destiny of a nation.

Three additional criteria were added to the list:

- A hero is part of the people’s expression. But the process of a people’s internalization of a hero’s life and works takes time, with the youth forming a part of the internalization.

- A hero thinks of the future, especially the future generations.

- The choice of a hero involves not only the recounting of an episode or events in history, but of the entire process that made this particular person a hero.

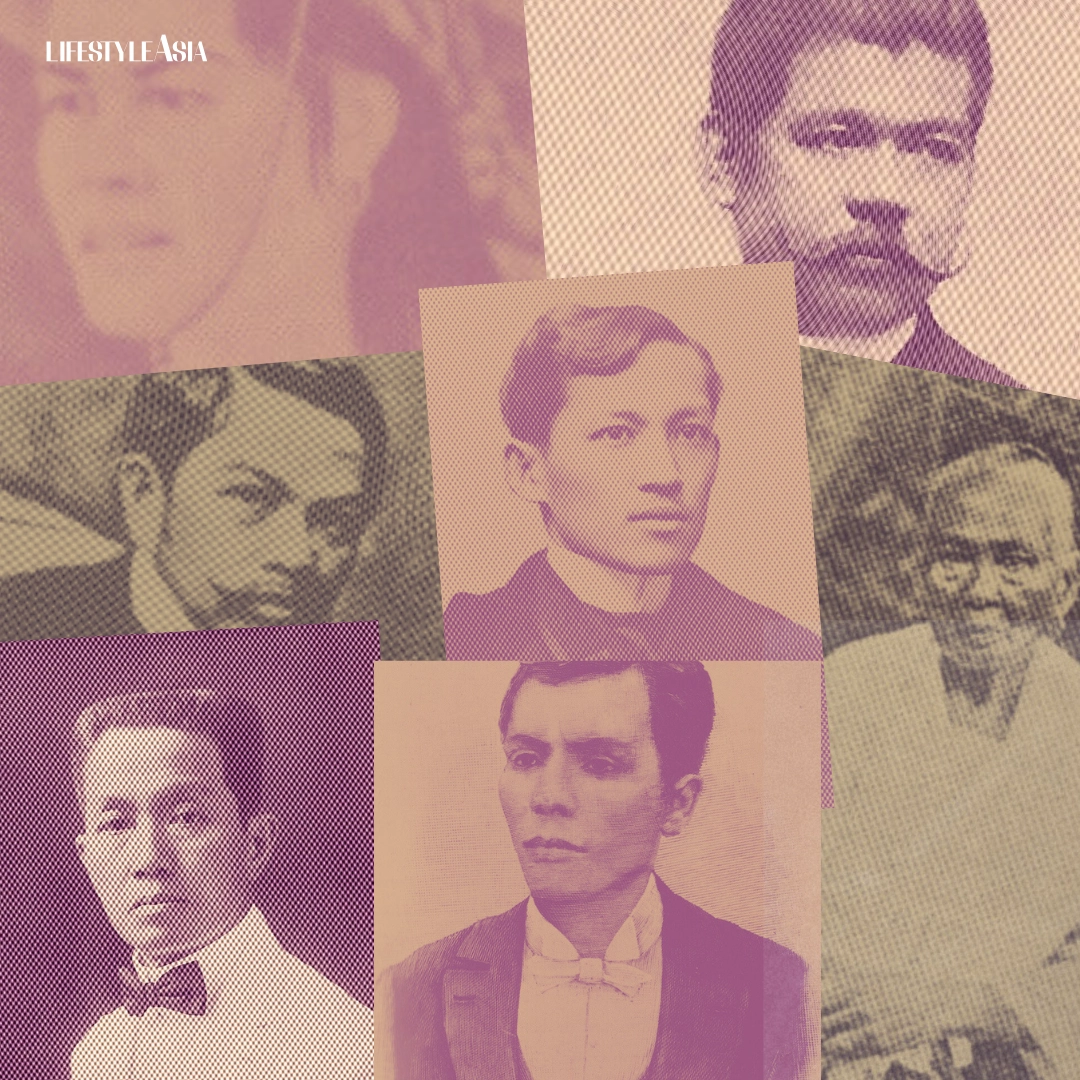

Then, in 1995, the body came up with a list of nine heroes to submit for consideration, namely: Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo, Apolinario Mabini, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Sultan Dipatuan Kudarat, Juan Luna, Melchora Aquino (Tandang Sora), and Gabriela Silang. However, since the submission of the list to then-Secretary Ricardo T. Gloria of the Department of Education, Culture, and Sports on November 22 of that year, no further action had been taken.

READ ALSO: What It Takes To Be A National Artist

There Are No National Heroes—But Should There Be?

Is this something that ought to be fixed? The answer to this will vary, depending on who you ask. The NCCA writes: “Heroes, according to historians, should not be legislated. Their appreciation should be better left to academics. Acclamation for heroes, they felt, would be recognition enough.”

But why are historians resistant to the idea of heroes being legislated?

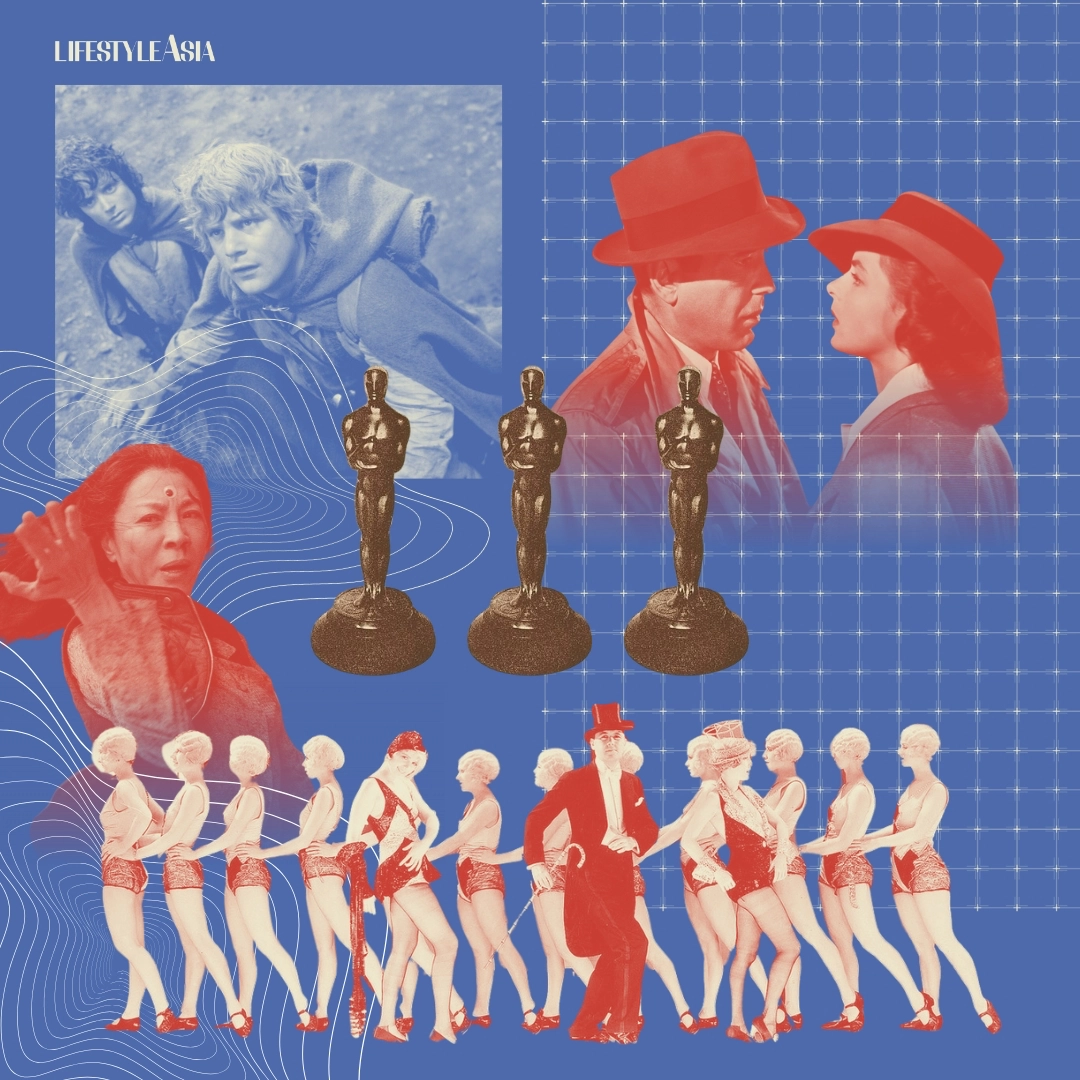

While having things formalized might give some sense of legitimacy, the process isn’t as clean-cut as you would think. As with any major awarding body—think the Academy Awards or Pulitzer Prize—the work of proclaiming anything as something (best book of the year, best picture, greatest hero, and so on) comes with its fair share of reactions. We’re not a hivemind; understandably, people walk on eggshells when it comes to legislating national heroes because none of us will ever reach a unanimous agreement on who really “deserves” the title.

Or, as the NCCA puts it, making it official will likely trigger “a flood of requests for proclamations” or even “bitter debates involving historical controversies about the heroes.”

This makes sense. For some, a hero’s deeds must be taken in the broader context: what their actions as a whole have done for a nation. This appears to be the concept that fuels the criteria set by this panel of experts. Yet others may also factor in these heroes’ lives as individuals, questioning whether they’re truly worthy of an entire country’s respect when certain actions—perhaps small in the larger scheme of things but still telling—might say otherwise. Take Juan Luna, for instance, whose name made it to the list. Would it be fair to call someone a national hero when he murdered his own wife (Paz Pardo de Tavera) and mother-in-law (Juliana Gorricho) during a fit of rage?

That said, I understand that the need to label things under a broad “national” category stems from the desire for unity or cohesion. If we’re to consider every differing opinion, we’d be left with no collective consciousness on historical and cultural matters—something rather important in the act of nation-building.

In the meantime, perhaps the best we can do on this solemn occasion is to honor what’s been done by heroes of the past and today’s altruistic individuals, while pondering on what it really means to “contribute to the quality of life and destiny of a nation” in an increasingly complex world.