We stumble upon all kinds of information and inspiration, but how much do we actually remember when we need them most? That’s where the commonplace book comes in.

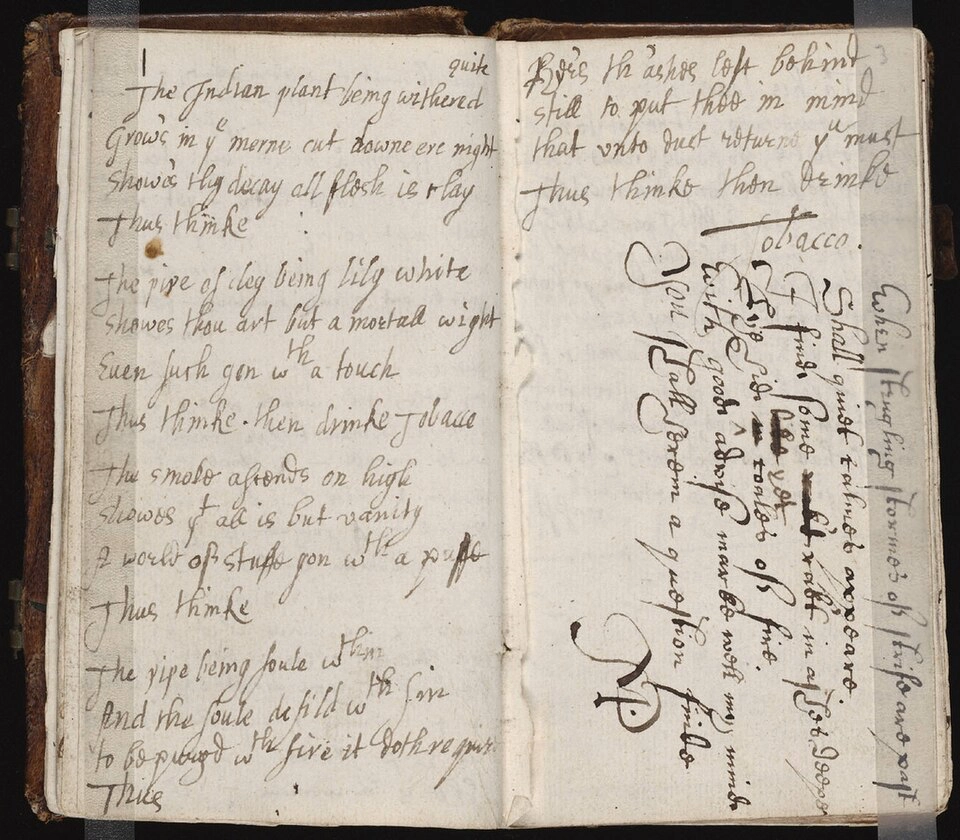

Humans have been keeping written records of the things they observe and learn about for centuries. So the idea of a “commonplace book” —a notebook specifically meant to collect thoughts, quotes, and any information one encounters through various sources—is really nothing new. Though it’s currently experiencing a resurgence in journaling and academic communities, it’s actually something great thinkers were already using throughout history, including Virginia Woolf, Leonardo Da Vinci, Mark Twain, Arthur Conan Doyle (who even gave his character Sherlock Holmes a commonplace of his own), and the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (his musings would later become the famous Meditations).

You might be wondering: why keep a commonplace notebook at all? Isn’t it enough to click “bookmark” or “save” on Instagram or X and call it a day? Well, if that method works fine for you, then by all means. Though if you often find yourself forgetting you ever saved these bits of information, or they simply disappear one day, you might find more use from keeping a dedicated notebook—whether that’s an analog or digital one. Think of it as a “second brain” of sorts, a kind of depository or database you can always return to when you need both inspiration and information.

If you’re curious, we’ll break it down to the essentials so you can start your very own commonplace book.

READ ALSO: Fountain Pens: Mightier Than The Sword

The Origins Of The Commonplace Book

The word “commonplace” comes from the Greek koinos topos, loosely translated to “general theme.” In ancient Greece, scholars organized knowledge into “places” they could reference to develop ideas or arguments. These were divided into two types: “specialized places” for fields like medicine, and “common places” for daily observations. Over time, this “everyday” information—whether recipes, book passages, quotes, or stray thoughts—was collected into what became known as a commonplace book.

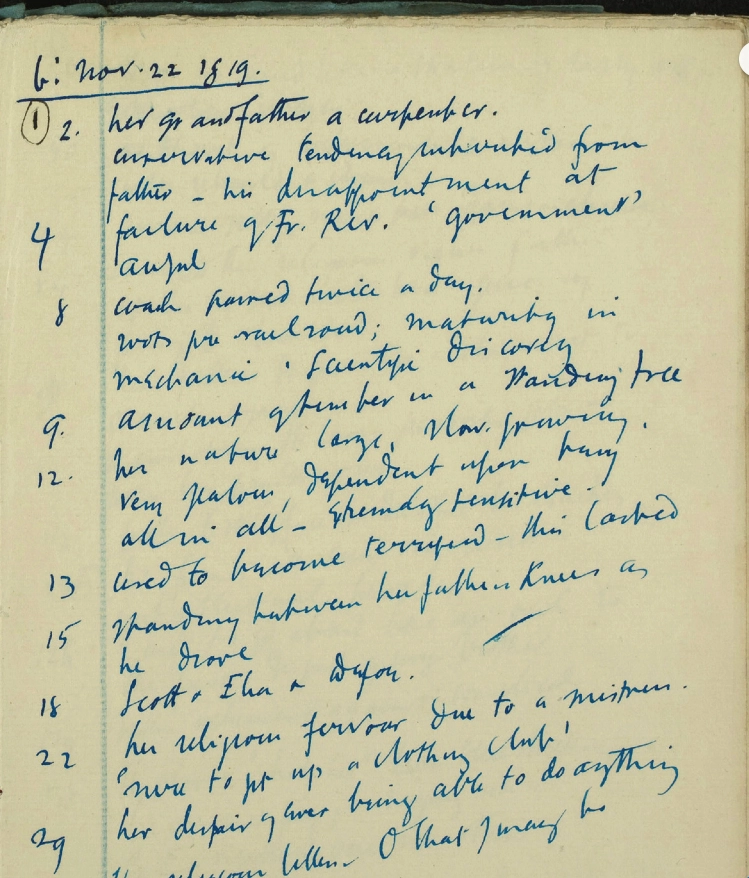

You can imagine how useful and necessary these books were before the internet or digital mediums, as people not only stored information in them, but actually returned to them when they needed to, developing their own systems of organization that helped them digest and clarify all the knowledge they encountered.

Marcus Aurelius kept a commonplace book filled with personal musings and learnings he encountered on the field, and while they were eventually published in the form of Meditations, these bits of information were originally meant to be a reference for himself.

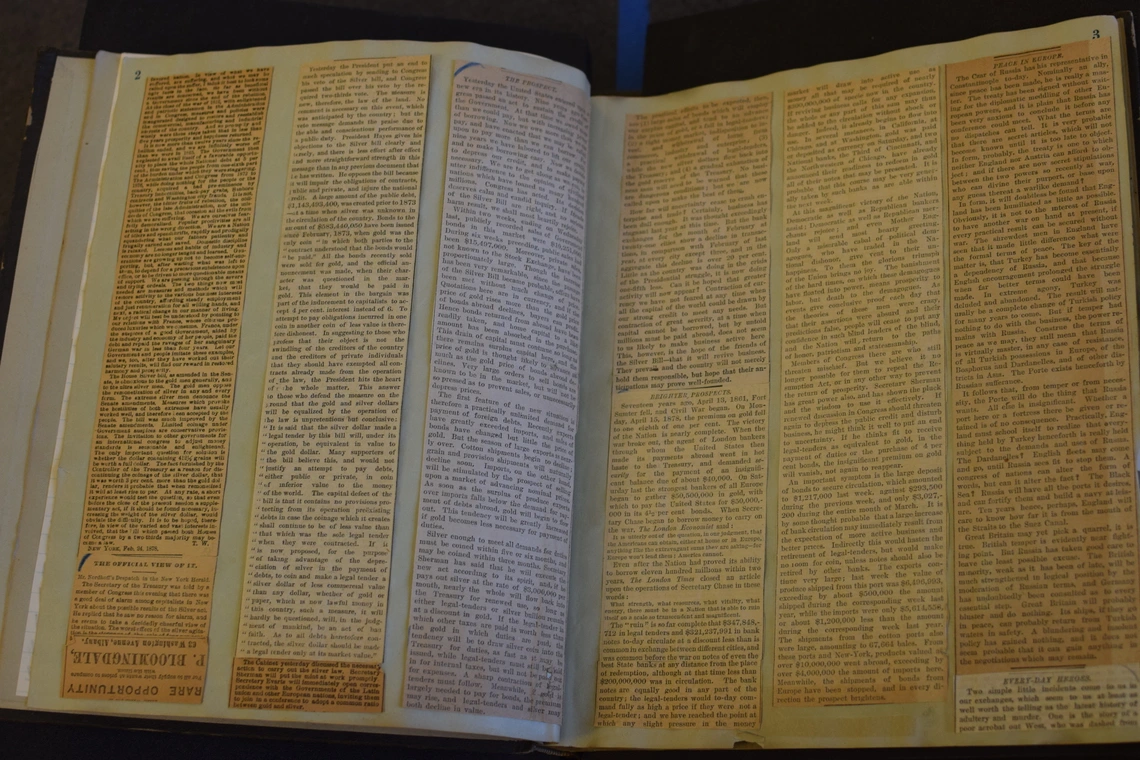

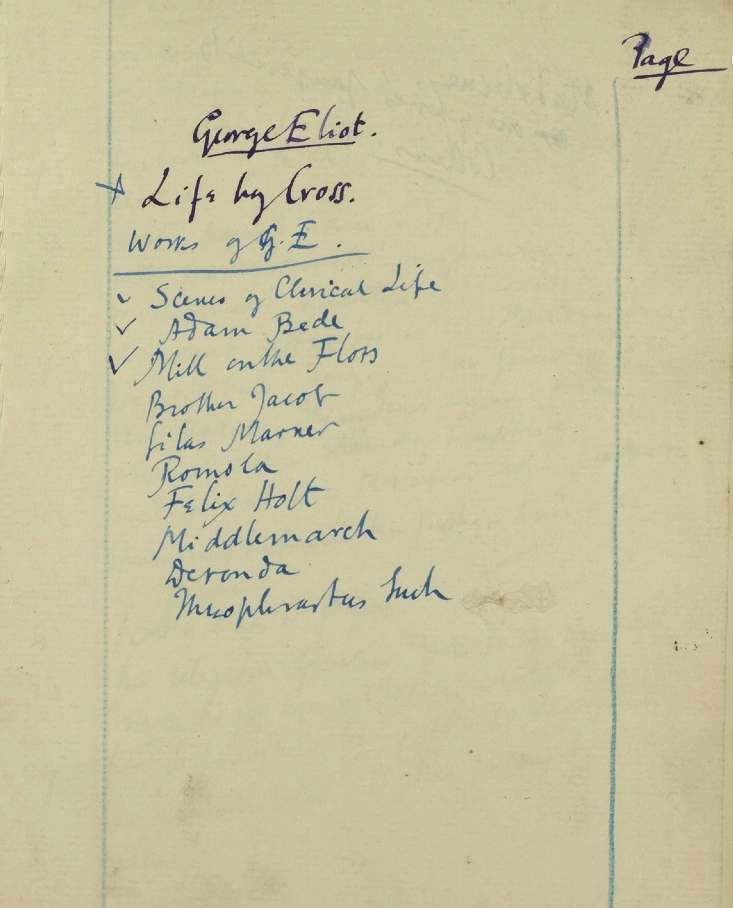

Virginia Woolf also kept a notebook with an index that tracked the various books she’d read, with pages of passages she wanted to remember and her own reflections on them. Mark Twain did something similar, though his was more like a scrapbook containing newspaper clippings, as well as poems and stories from various periodicals.

And of course, who can forget Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous notebooks, which held everything from blueprints of his inventions to personal observations.

I guess if we want to oversimplify, you can think of the commonplace as a journal for nerds—but I’d prefer to call them active, voracious thinkers. Anyone can keep a commonplace, and unlike a diary—which might expect daily confessionals of the personal kind that some people aren’t keen on committing to—it doesn’t ask for much. It’s simply there whenever you need it, ready to hold the things you might forget (but may very much need) weeks, months, or years from now.

“Daily diary apps and self-improvement podcasts and confessional Instagram stories evince a belief that to grow as a person you have to be entirely, unflinchingly forthcoming,” writes Charley Locke in her The New York Times article “Commonplace Books Are Like a Diary Without the Risk of Annoying Yourself.”

She continues: “But I couldn’t catalog my flaws without flinching. And I don’t think I need to. That’s part of the point of reading, I think: When I find myself too earnest, too impatient, too much, I can be in conversation with other minds instead.”

Developing A Second Brain

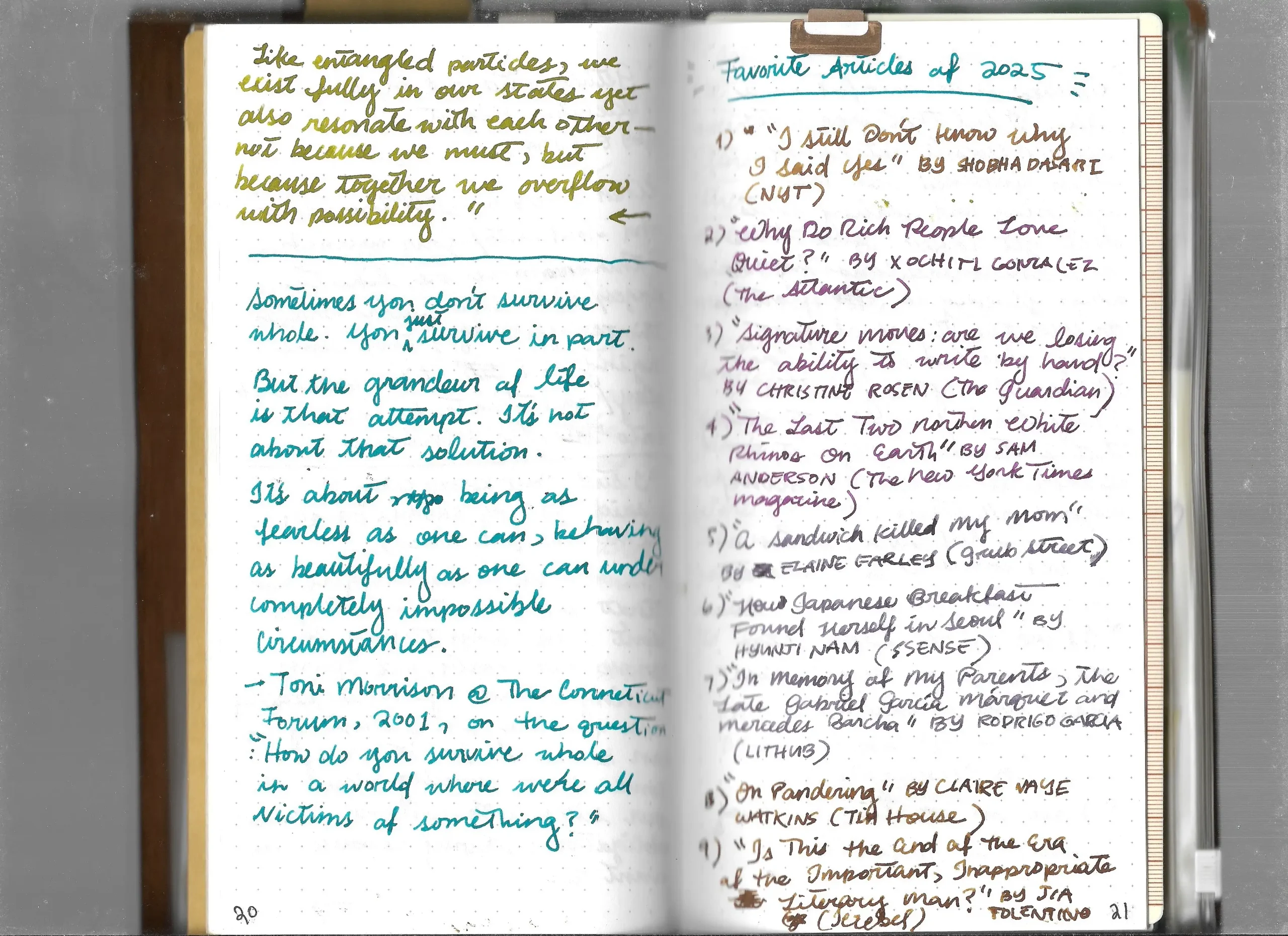

As a writer, I find my inner life has changed for the better since keeping a commonplace book of my own. Sure, I still save recipes and poetry stanzas on my digital Instagram collections, but I usually jot them down on my dedicated notebook as well, especially when I feel like I’ll need them someday. It’s more a gut feeling than anything else—even if I don’t necessarily “need” certain bits of information, I’ve found myself feeling more inspired perusing them later on, especially when I’m searching for essay ideas.

I’m an incredibly forgetful person, and I doubt I’m the only one. If we do an honest assessment of “knowledge I encounter vs. knowledge I actually retain,” we might realize we skim through and forget most of it. Or we find ourselves frustrated trying to recall something that moved us, but not being able to access it, the source lost within the piles of likes, saves, and bookmarks we keep.

The things we store in our commonplace books don’t have to be profound. I keep bits and bobs of real-life conversations I overhear, song lyrics, lines of poetry, film dialogue, and book quotes in mine. Sometimes, if I encounter an interesting video essay on YouTube, I’ll just jot down its title and creator, maybe put in a few lines or fragmented words that struck me, then end it at that. The point is that we’re recording things with care and intention, through a practice that has us investing in our lifelong learning.

A commonplace book is also a valuable resource when digital decay looms in the background. I wrote an article explaining the phenomenon, but to make a long story short, there are no guarantees that any information on the internet—however compelling it may be, however well-maintained it is—will be there forever. That video of your favorite musician talking about their songwriting process might just disappear one day, as will that recipe for chocolate cupcakes. So, the best thing we can do is commit them to pen and paper, or if you prefer digital methods (though again even those are flimsy), type them down in a notes app of your choice.

How To Keep A Commonplace Book

There’s no “correct way” to keep a commonplace book—just the way that works best for you. Though the common (heh) denominator in most methods is a core system of organization. To my mind, that’s what distinguishes a commonplace from “just a notebook where I jot things down willy nilly.” Not that there’s anything wrong with the latter, but the point of the book is to be a place you can easily navigate, one where ideas don’t get lost in all the noise.

So whether you’re using a note-taking app or ever-reliable physical notebooks, here are some ways you can start a commonplace book of your own.

Use A Platform Or Notebook That Can Hold A Lot

You’re free to use any notebook you want to create your commonplace book, but it’s always better to stick with one that has a lot of pages. This keeps as much information as possible, within a longer timeframe, all in one place—unless you prefer splitting everything up into smaller volumes. The second option works fine, but keeping track of so many volumes so early on can make it difficult to find the information you need. Of course, no notebook has infinite space, so you’ll need to split things into different parts eventually, but the less moving parts you have, the easier it will be to collect everything. This isn’t really a problem in a unified note-taking app with virtually unlimited storage.

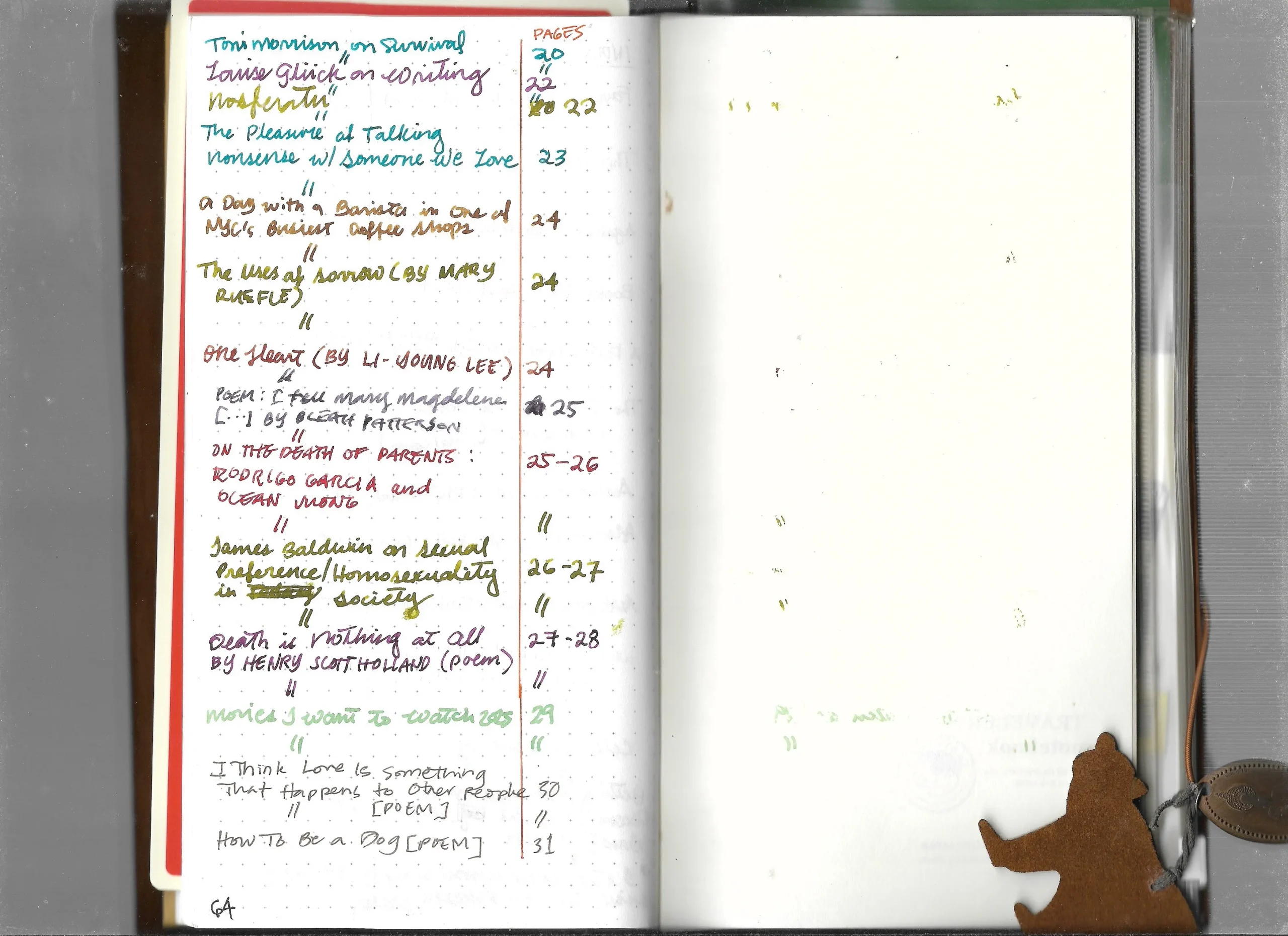

Create An Index Or Tagging System

Perhaps the most important part of the commonplace book, the index works pretty much the same way any book index does. It presents pertinent topics or keywords, short enough to quickly reference yet direct enough to give you a good idea of what they’re about, and the corresponding page numbers where you can find them.

For this reason, if you’re using a physical notebook, it’s better to get one that’s already paginated: certain brands like Leuchtturm1917 and Midori do this exceptionally well, and even provide notebooks with their own printed index pages. Though really, you can use any notebook and number it yourself, if you’re willing to put in the effort. Plus, I find that thick, blank notebooks give you more freedom to make indexes as lengthy as you want, since you can decide how many pages you’ll allot yourself.

As for how to use the index, that would depend on how you’d like to categorize your information. You can group things by general topic, or get really specific. For instance, you can just have one category called “Recipes,” then jot down every page number that contains a recipe beside it. Or, you can write “Quotes by Virginia Woolf On Friendship,” and do the same thing, listing down any pages that contain quotes related to the topic. Sooner or later, you’ll have an organized and handy index you can refer to when you want to search for something later on.

If you’re using a digital platform, most note-taking software features tagging systems that also make indexing easier. Just jot down whatever you encounter, place a tag on it, and when you need it, click the tag: you should be able to see a collection of things under that category. Most digital platforms let you get as specific as you want to, even allowing you to place multiple tags on a note to make it easier to pinpoint.

Remember, Work With Your Brain, Not Against It

You don’t need to color-code every entry or invent a complicated system. Everyone organizes information differently, and what works for one person might feel like overkill for another. The real secret to a useful commonplace book is consistency. If your method feels tedious, you’ll quickly lose momentum, and that defeats the whole point. Not into copying long passages word-for-word? Snap a photo or screenshot and paste it in. Prefer keywords, jotting just a title and author, or a line or two from a podcast? Perfect. Do whatever makes it easiest for you to capture what matters. Remember, a commonplace book is probably one of those few, blessed sanctuaries with no audience other than yourself: be honest about what you actually need to remember, and, cliché as it may sound, have fun with it.