We may eventually outgrow the charming tales of our early years, but children’s literature—and the joy of story time—deserve to be preserved, celebrated, and remembered for how they shaped our first understanding of the world.

It’s World Children’s Day today, and that got me thinking about storybooks. I grew up in a generation, perhaps one of the last, where storytime was still an integral part of the education system. In fact, when I think about kindergarten, the most prominent memories were peaceful afternoons with our teacher, who, without fail, would always read us a story, complete with special voices for different characters (shoutout to you, Ms. Tippin). There was an almost sacred silence to the practice, and being able to calm a whole room of antsy kids with a simple picture book tale was nothing short of a miracle.

I also remember evenings spent with my father, who’d read Sesame Street bedtime stories aloud to me. When my younger siblings came into the world, I carried on the practice and read them storybooks too (one about a baby chimp titled Hug, by Jez Alborough, was a particular favorite).

There’s an ephemerality to storytime because children eventually grow “too old” for them, or shift from the ones being told the stories to the ones doing the telling—and that’s normal. Yet nowadays, at the expense of sounding like a grandmother, I’m seeing tiny hands grasping big screens instead of these books, and it concerns me for both sentimental and practical reasons.

READ ALSO: The Price Of Loving A Pet

Why Reading Storybooks Matters

In a video for The Times titled “What happens to a baby’s brain when you read to them,” child neuroscientist, psychologist, and professor Sam Wass introduces the idea of “brain synchrony,” which happens when a parent reads to their child.

“[It’s] two brains beating to the same rhythm at the same time,” he explains. “Emily [the mother in the video’s test] is talking, and her brain is synchronizing to the language that she’s producing, and Alba’s [her baby’s] brain is listening to what Emily is saying and tuning into the same rhythm.”

He continues: “And we think that there’s something really, really important about these moments of connectedness, this being in the same state, at the same time. It’s important for early language development. It’s important for emotional understanding and self-awareness. But it’s also important for things like promoting relaxation. Strengthening the kind of quality and mutual understanding in a relationship between a parent and a child. So there are so many different things that have been proven by really really good quality studies to be improved by shared reading.”

The thing is, whether or not you intend to become a parent yourself, understanding the importance of children’s literature is the first step to building a collective culture that supports the continuation of these kinds of stories.

Why Storybooks Move Beyond Literacy

Nowadays, I’ve noticed more parents pacifying their children through vibrant screens to gain a few moments of peace. The sight of storytime is so rare that when I did see a young mother quietly reading to her baby in a coffee shop, my heart swelled.

But hey, I can’t make judgements because I’m not a parent myself—it’s undoubtedly a difficult job that pushes you to seek the quickest way to pacify a screaming toddler. Storytime requires a level of patience and energy busy adults can’t always give. Still, to abandon the practice altogether is to forget the reasons why it matters beyond helping your child build their vocabulary or literacy skills from a young age. These narratives offer them a window to a vast world, and it’s probably one of their earliest brushes with vital concepts they’ll encounter later on in life: about love, friendship, happiness, and yes, even things as complex as death.

Then, as Professor Wass explains in The Times video, there’s that element of connection you can’t get from handing your child a shiny device. Books don’t demand much other than your voice and presence, yet those things can mean a lot to developing hearts and minds.

Back in high school, we were tasked to read to a kindergarten class. I grabbed the cutest book I could find, but had no idea it was a wordless picture book—and so I was left to make up a story on the spot about two mice who lived together and were the very best of friends. As I narrated it, I asked the kids questions (and I can say it really takes a lot of effort to keep them engaged) like who their best friends were in the group, or how much they loved them, and seeing them smiling, pointing at one another, and hugging each other was enough to show me just how much a story can affect people. Years down the line, they might forget all about that moment, but right then and there, they were encouraged to think about the things that mattered in life; I’ll let that anecdote speak for itself.

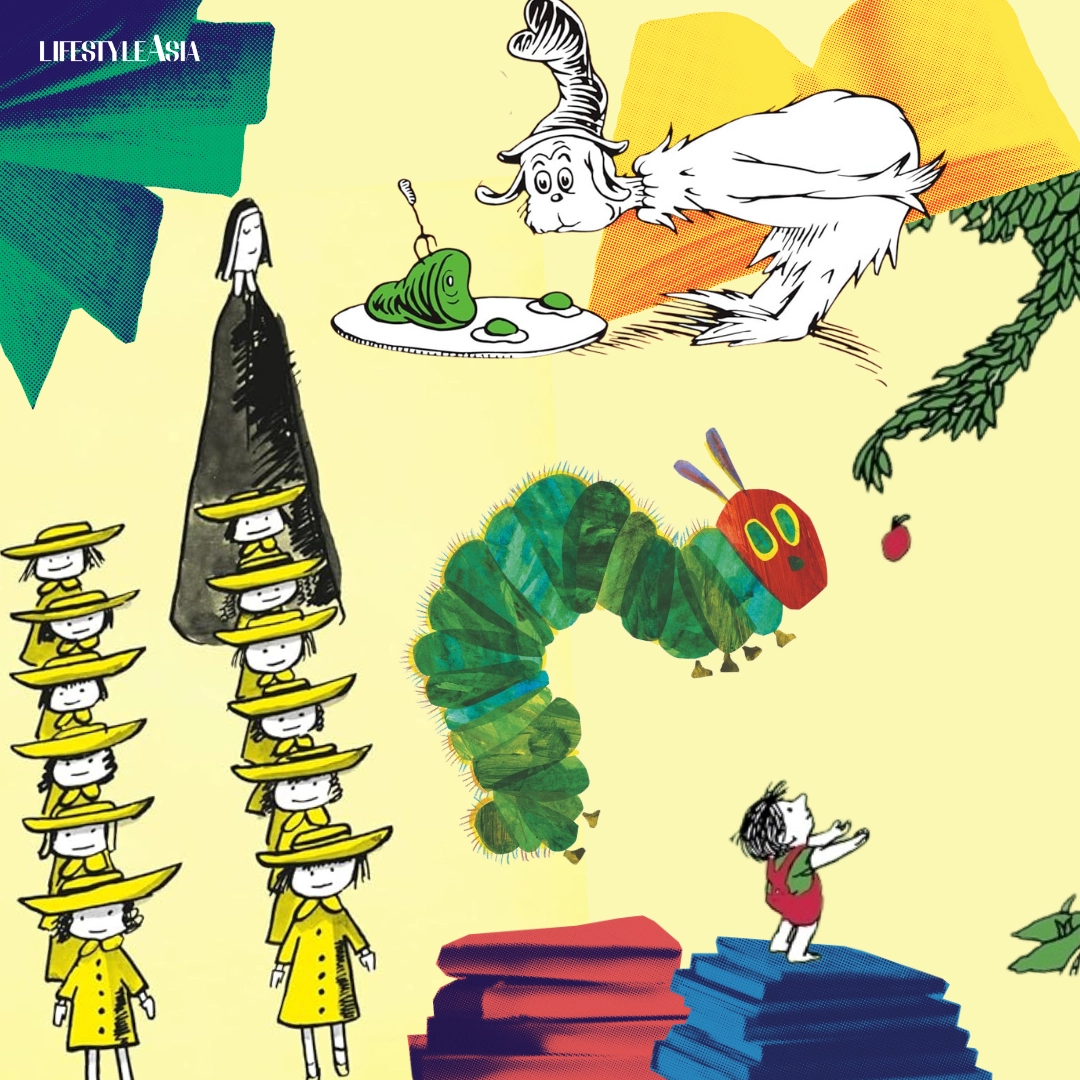

A Look Back At Beloved Childhood Storybooks

Let’s revisit the titles that many of us encountered in the days when things were simpler.

The Very Hungry Caterpillar

Arguably the most iconic children’s storybook out there—its cover so recognizable, you only need to see it to name it—Eric Carle’s A Very Hungry Caterpillar admittedly doesn’t have much going on. It’s, quite literally, about a very hungry caterpillar who eats his way through fruits and leaves until he fattens up then transforms into a beautiful butterfly. (Gasp, spoiler!). Yet Carle teaches us that some stories don’t need to have some profound, earth-shaking lesson beneath them. Sometimes kids just want to see a cute caterpillar, and its visuals are a feast for the eyes.

(Though looking back, the story does spark a bit of envy: we wish we could go through a fabulous metamorphosis after feasting on lechon and desserts during the holiday season, but that’s probably why this is considered a work of fiction.)

The Rainbow Fish

Remember this diva? Marcus Pfister’s 1992 storybook remains a favorite for the glittering effects applied to its main character, a fish that sparkles unlike any in the ocean. Other fishes envy Rainbow Fish, one even asking if they can take a single scale, but the protagonist harshly refuses the request. Later on, however, the Rainbow Fish discovers that sharing one’s gifts grants more than keeping them all to themselves. The story is actually a pretty compelling showcase of community and the kind of deep fulfillment you can derive from generosity.

Strega Nona

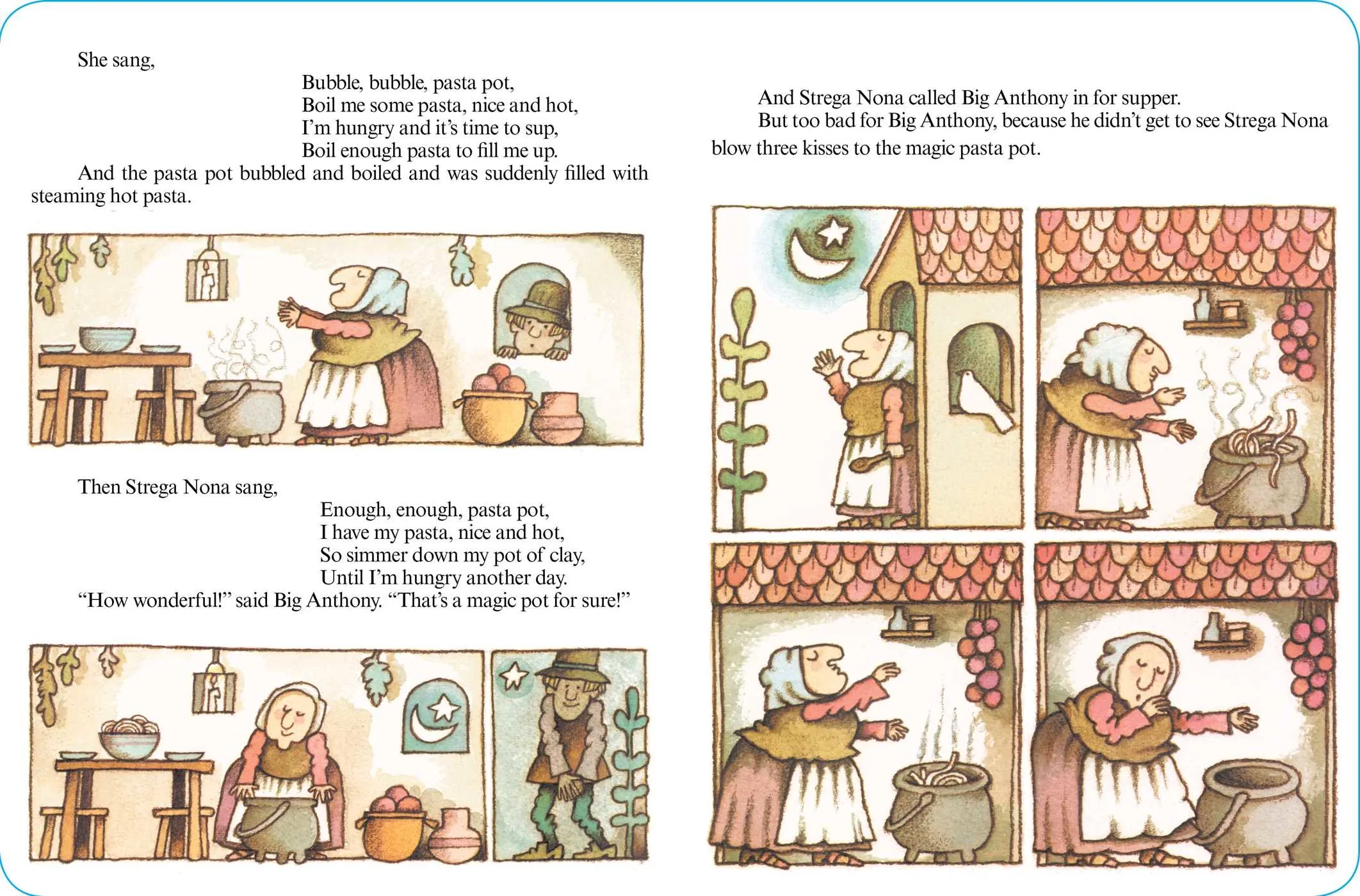

You’ve heard of witches casting curses and brewing potions in their cauldrons…but have you heard of one that cooks a mean pasta? Rendered like a folktale both visually and in writing, Tomie dePaola’s Strega Nona tells the story of an eponymous witch in Calabria, Italy who, growing too old to do all her chores, tasks a young man named Big Anthony to help out.

He notices her cooking delicious pasta from her magic pot one evening and decides to give it a try when she’s out of the house, only to endanger the townsfolk with an uncontrollable noodle explosion. This one is actually a personal favorite of mine, and it’s mostly because I wanted so badly to taste that pasta—but the story is also a pretty entertaining cautionary tale about what happens when we don’t follow the wisdom of our elders (though some will joke about Strega Nona being selfish for keeping all that good pasta to herself, which, okay, is a pretty funny thing to consider in hindsight).

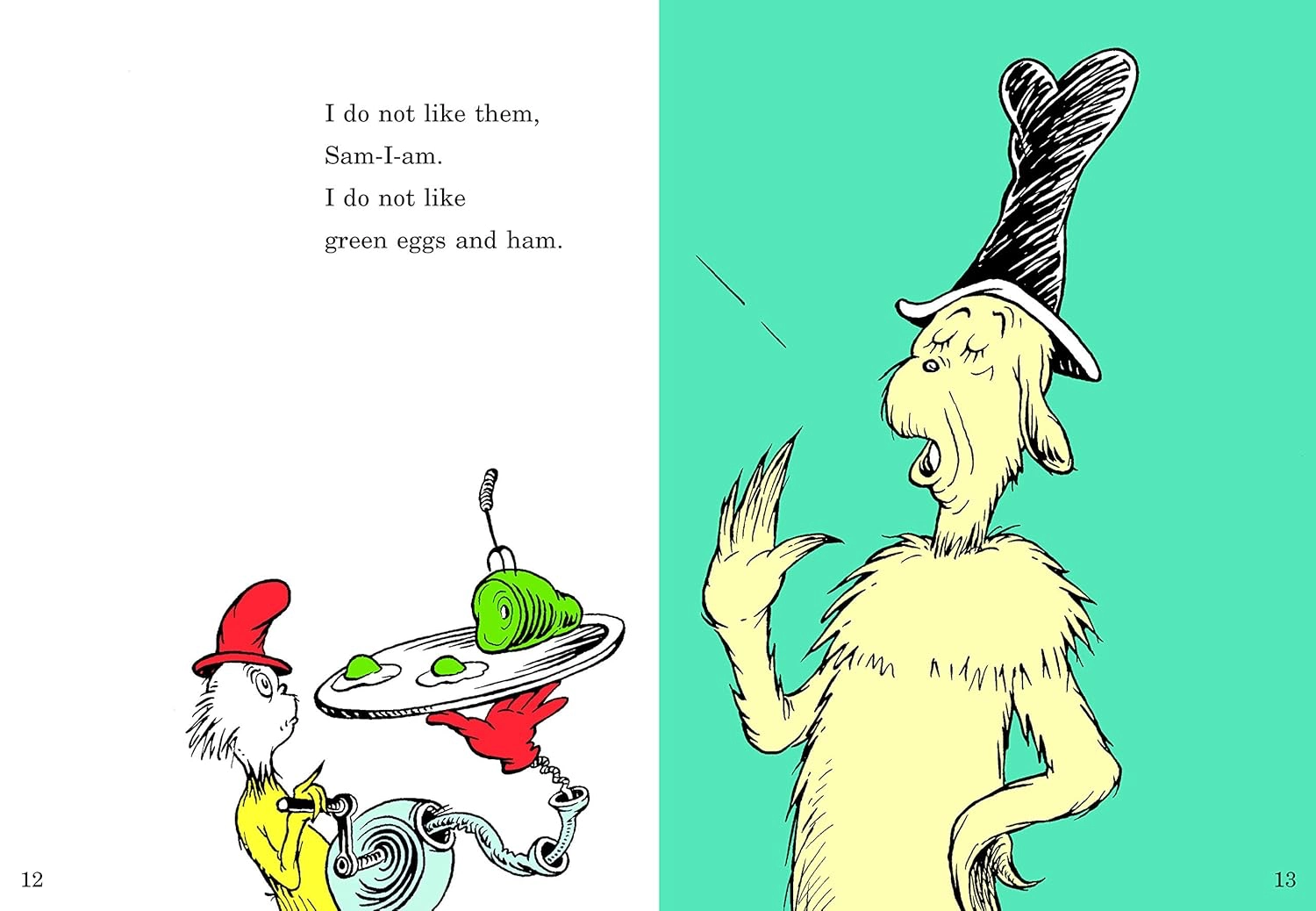

Green Eggs and Ham

Who can really beat the rhymes that Dr. Seuss gifted the world with? Aside from his famous Cat in the Hat and The Lorax, his 1960 storybook Green Eggs and Ham has also been a staple on the shelves of schools, libraries, and homes.

Does any of it make sense? Well, not really, and who actually eats green eggs and ham? But the rhyme scheme is so fun to read and say out loud, we’ll forgive the unappetizing imagery. Plus, it teaches kids to say “I do not like them” in the funniest way we know how, something that’ll undoubtedly be an indispensable phrase in the lexicon for years to come.

Madeline

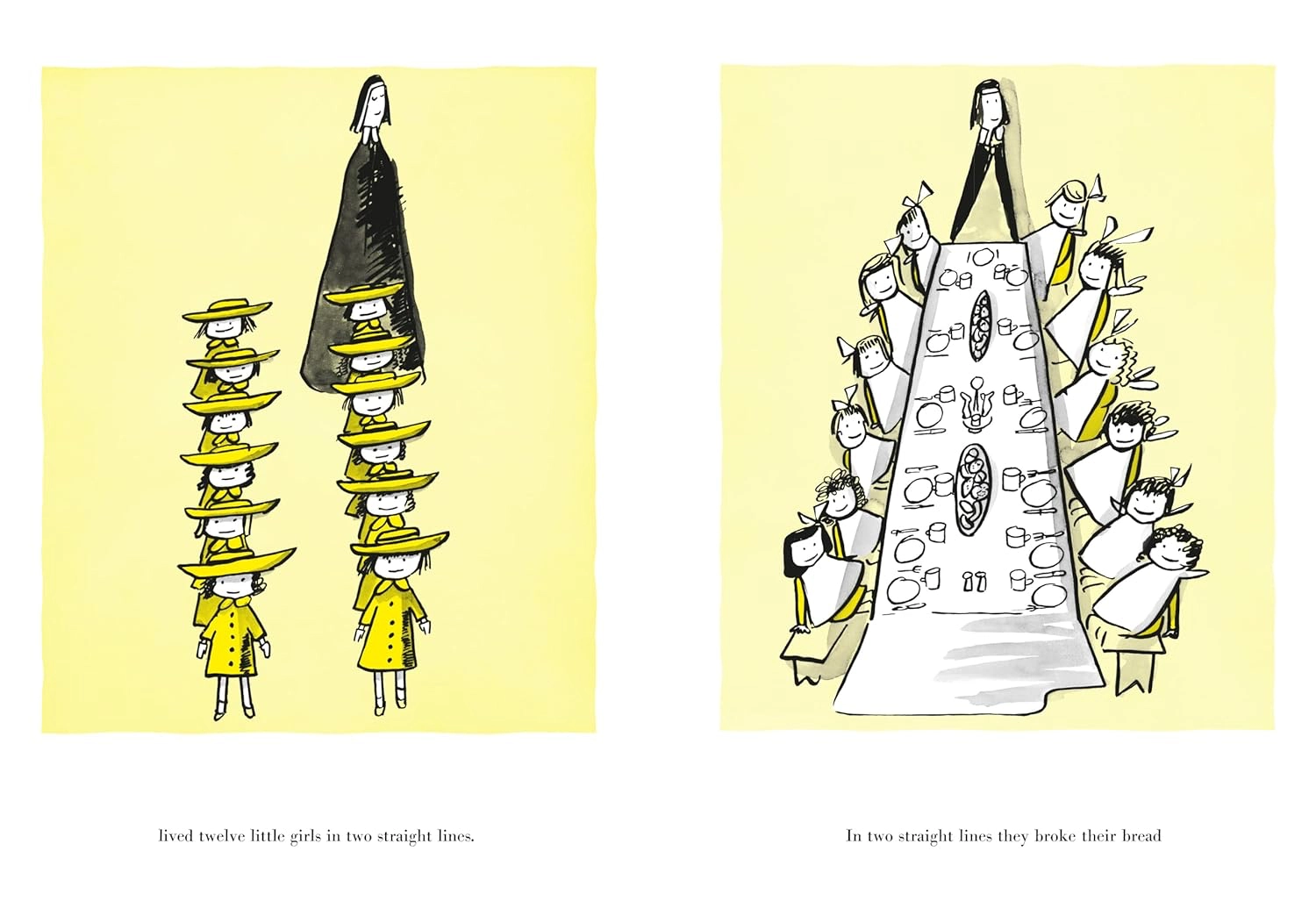

Recite it with us: “In an old house in Paris that was covered with vines, lived 12 little girls in two straight lines.” Yet another classic so widely loved it was adapted into multiple shows and films, Ludwig Bemelmans’ 1939 Madeline remains a wholesome, timeless read.

First off, its titular Madeline, the “littlest one” in the group, was someone most plucky girls could relate to. There’s also something so charming about Bemelmans’ messy sketches of Parisian life, seen through the eyes of students in an all-girls boarding school and their caretaker, the ever-patient nurse Miss Clavel. It’s an honest portrayal of girlhood at its silliest and sweetest.

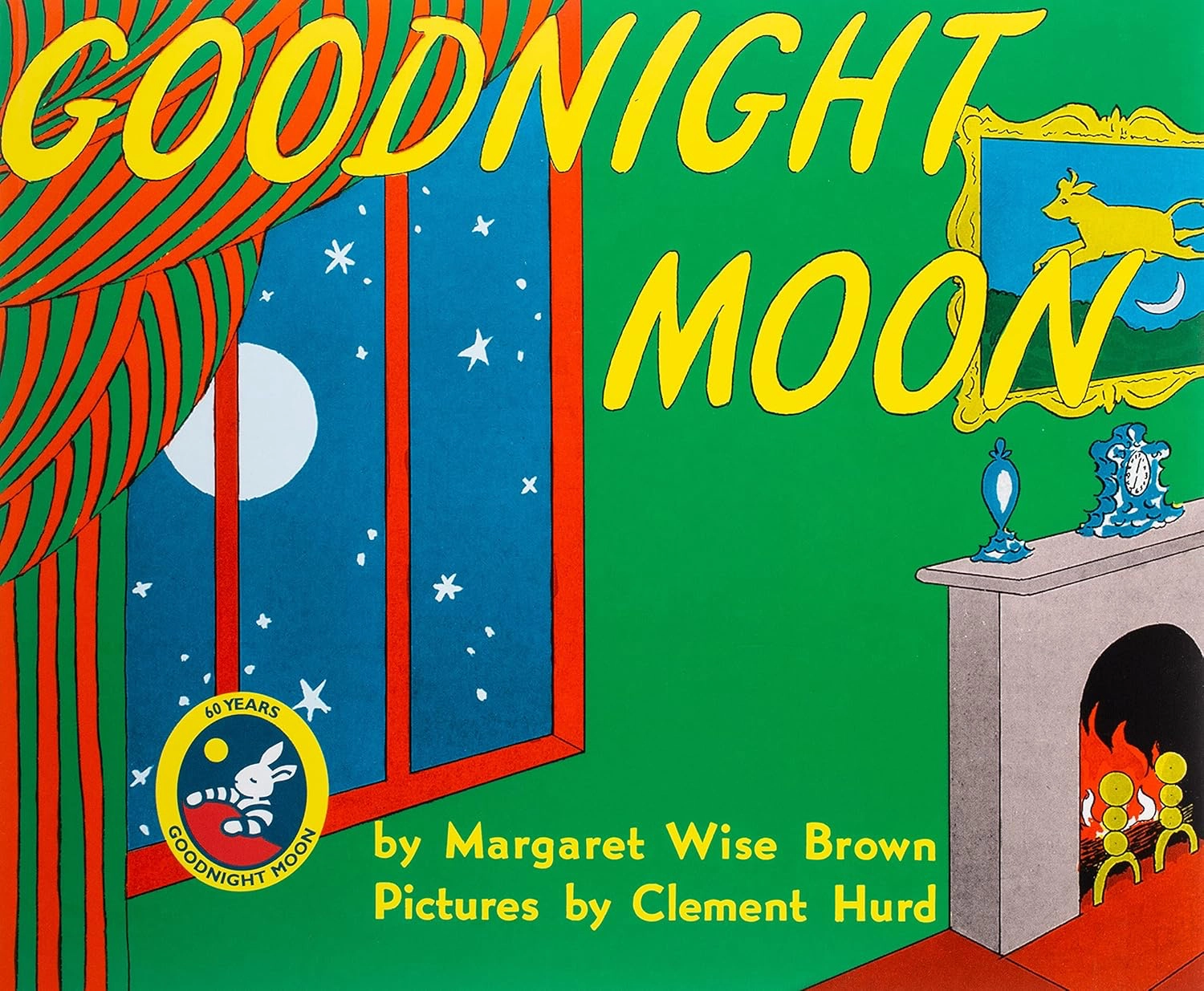

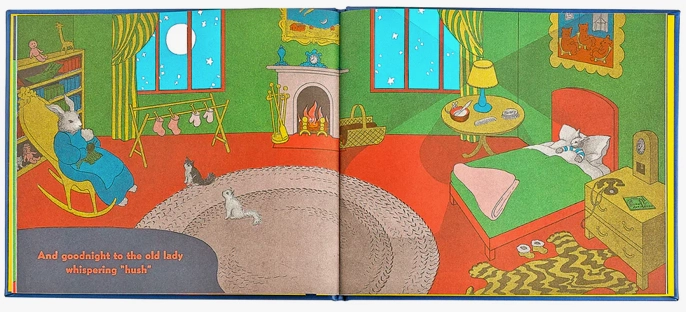

Goodnight Moon

As the title suggests, Goodnight Moon is the quintessential bedtime story, one that’ll have little ones nodding off before you know it. Written by Margaret Wise Brown in 1947 and illustrated by Clement Hurd, it follows a small anthropomorphic rabbit as it says “good night” to the objects in its room and the world outside, including, of course, the moon.

It’s a warm hug in book form, its gentle repetition soothing in the same way counting sheep is. Perhaps that’s why it has sold more than 11 million copies worldwide and been translated into numerous languages.

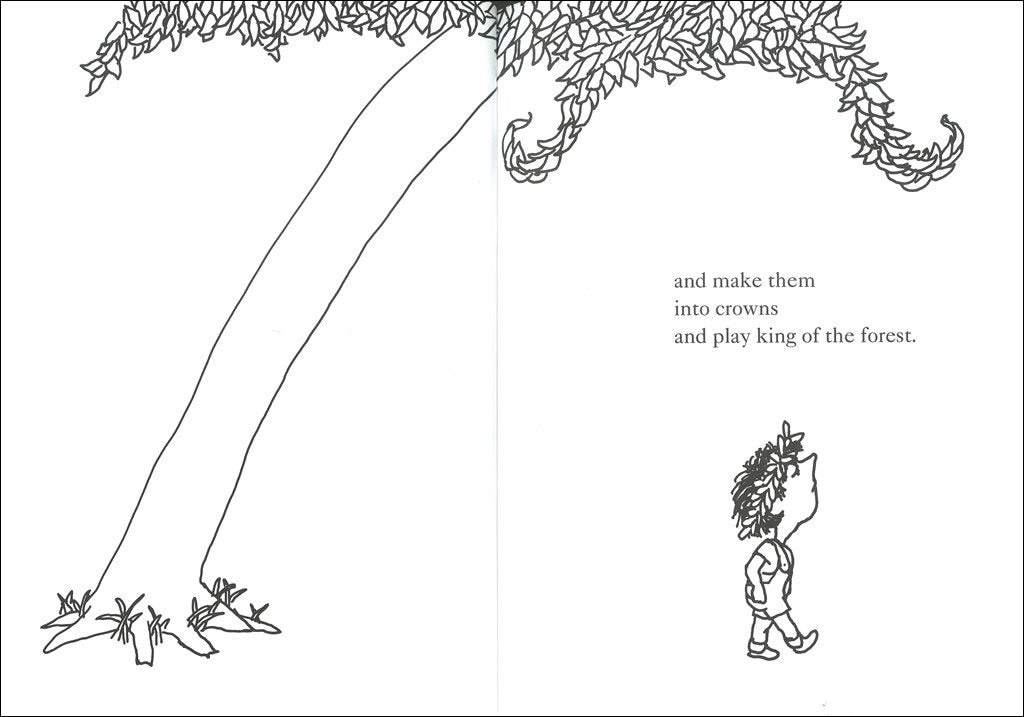

The Giving Tree

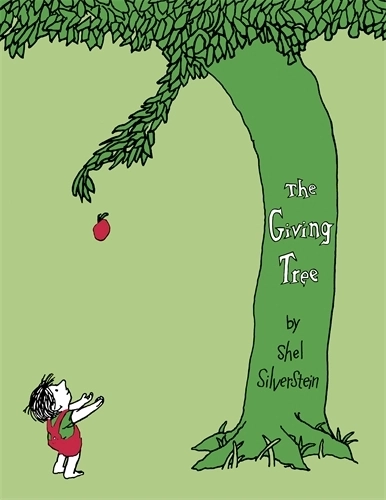

We’re moving into legendary tear-jerkers now, the first of which has to be Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree. Its cover is an image we feel in our bones, a little boy with his arms outstretched and a living tree dropping an apple for him. The story chronicles the growth of this boy, who forms a strong bond with a tree that offers him everything she can throughout the years, from shade to apples.

Yet as he gets older, she finds herself giving more and more, the boy becoming a man whose demands grow with him. Those who’ve read the story know that it’s an allegory for parenthood: how our relationship with our parents, willing to give us the world, starts with simple joys yet becomes more complicated as we get older. Though we could also read it as a depiction of our bond with mother earth, who gives us a lot without asking for much in return.

Either way, I remember my tiny heart breaking as our teacher read it to us. Yet the story ends on a fairly happy note, a kind of full circle moment that shows how we’ll ultimately want to return to the simple joys of life, when all is said and done.

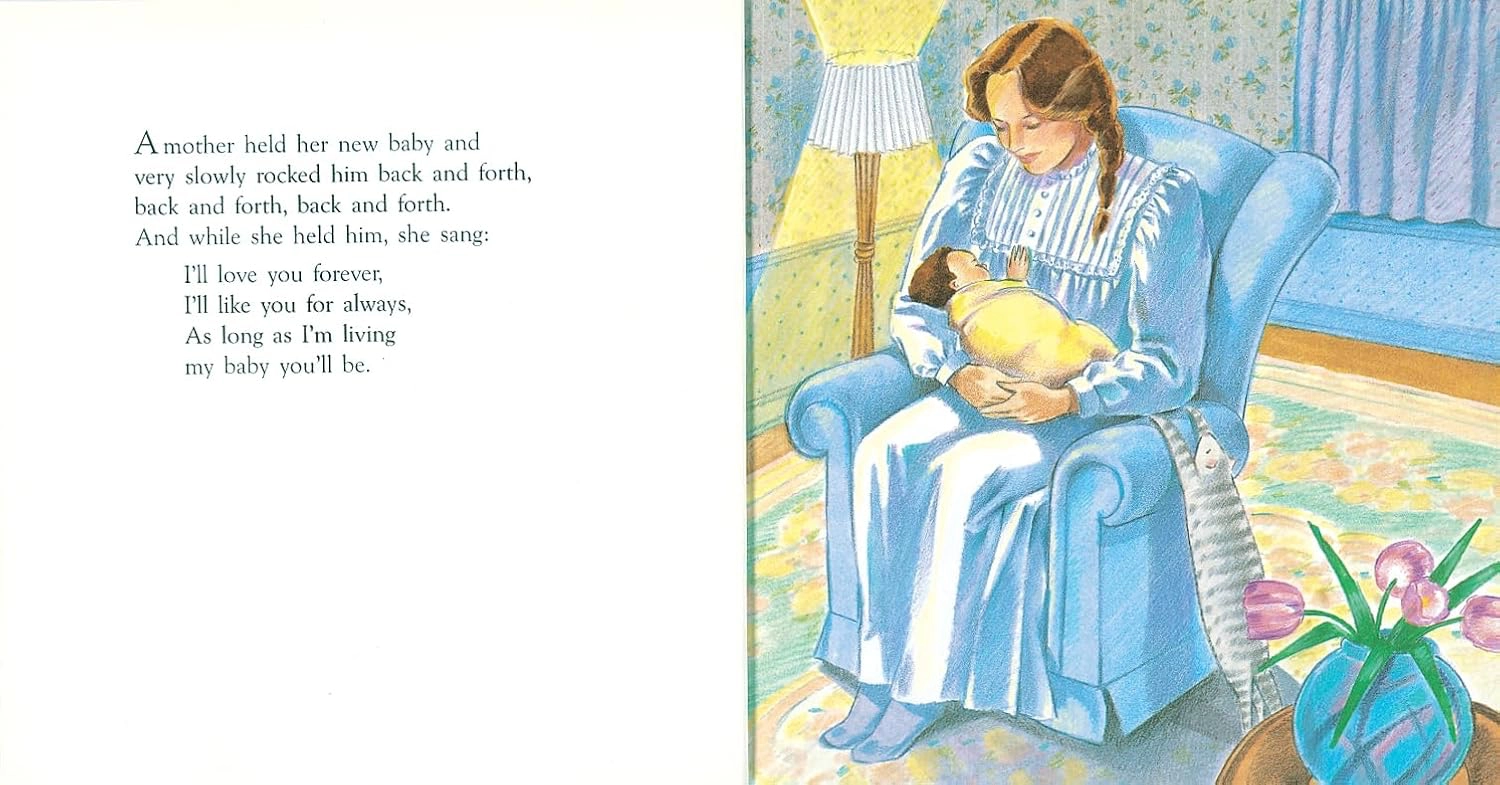

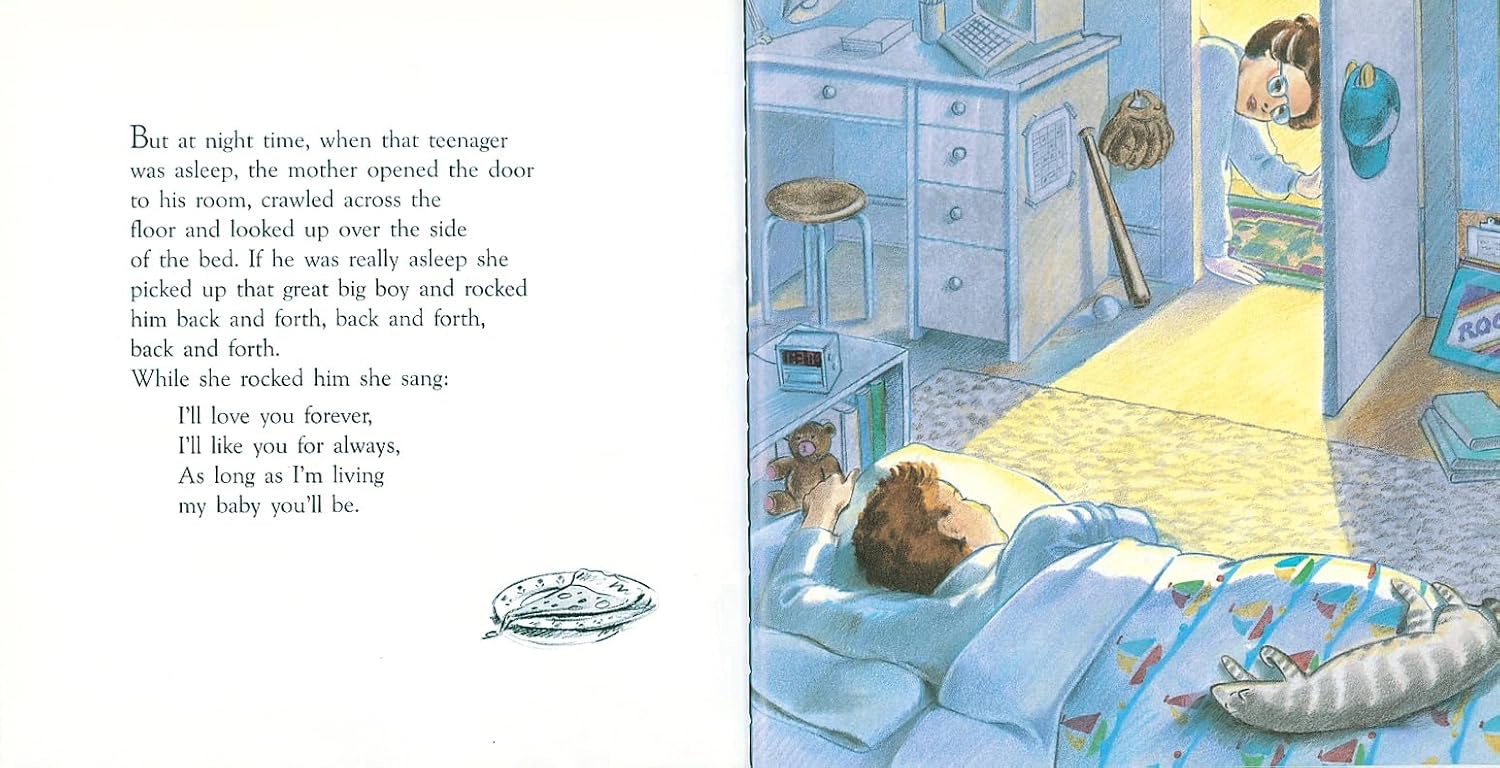

Love You Forever

And last but certainly not least, a storybook that only becomes more heart-wrenching as you age. Love You Forever already tugged at our hearts when we were young, with its tale of a mother whispering her love to her growing son is sob material from the start. But rereading it as an adult hits different: it confronts us with the reality that our parents will grow older too, and yes, one day, they’ll leave us.

There’s a reason why it feels so authentic. Written by Robvert Munsch in 1986, and illustrated to perfection by Sheila McGraw, Munsch came up with the story after his wife experienced the loss of two babies through stillbirth, the mother’s lullaby based on a song he’d sung during her pregnancy.

And then there’s the ending—where the roles are reversed and a new cycle of life begins—that absolutely wrecks you. It’s one of those stories that somehow gets more powerful as time passes. (And if your parents or teacher sang the mother’s message while reading it aloud? That’s another −1000 HP of emotional damage.)

How Storybooks Endure

We owe a great deal to the writers, illustrators, teachers, and parents who devoted time to telling us stories that shaped who we are today, even if it might not be very obvious to us.

Let’s be honest: we might’ve stopped reading the storybooks that constituted our childhoods, but we never quite forgot them. All it takes is seeing its cover, a picture, or even a few words, and suddenly you’re a kid again, still learning about how the world works. It’s nostalgia at its finest, and there’s no harm in taking a trip down memory lane.