From a rhinoceros species that lived in what’s now Fort Bonifacio to giant “cloud rats,” here are six extinct animals that once called the Philippines home.

We’re well aware of how biodiverse the Philippines is today, but our natural history is just as fascinating, especially when you look back thousands of years. While we never had dinosaurs à la Jurassic Park (at least as far as current evidence shows), a surprising cast of now-extinct animals once called these islands home. Of course, our archipelago was a very different world back then. Curious? Let’s jump back in time to familiarize ourselves with these giant creatures (and yes, learn more about why we don’t have dinos).

READ ALSO: Spot These 10 Beautiful Birds In Your Manila Neighborhood

Extinct Animals From The Land Before Time

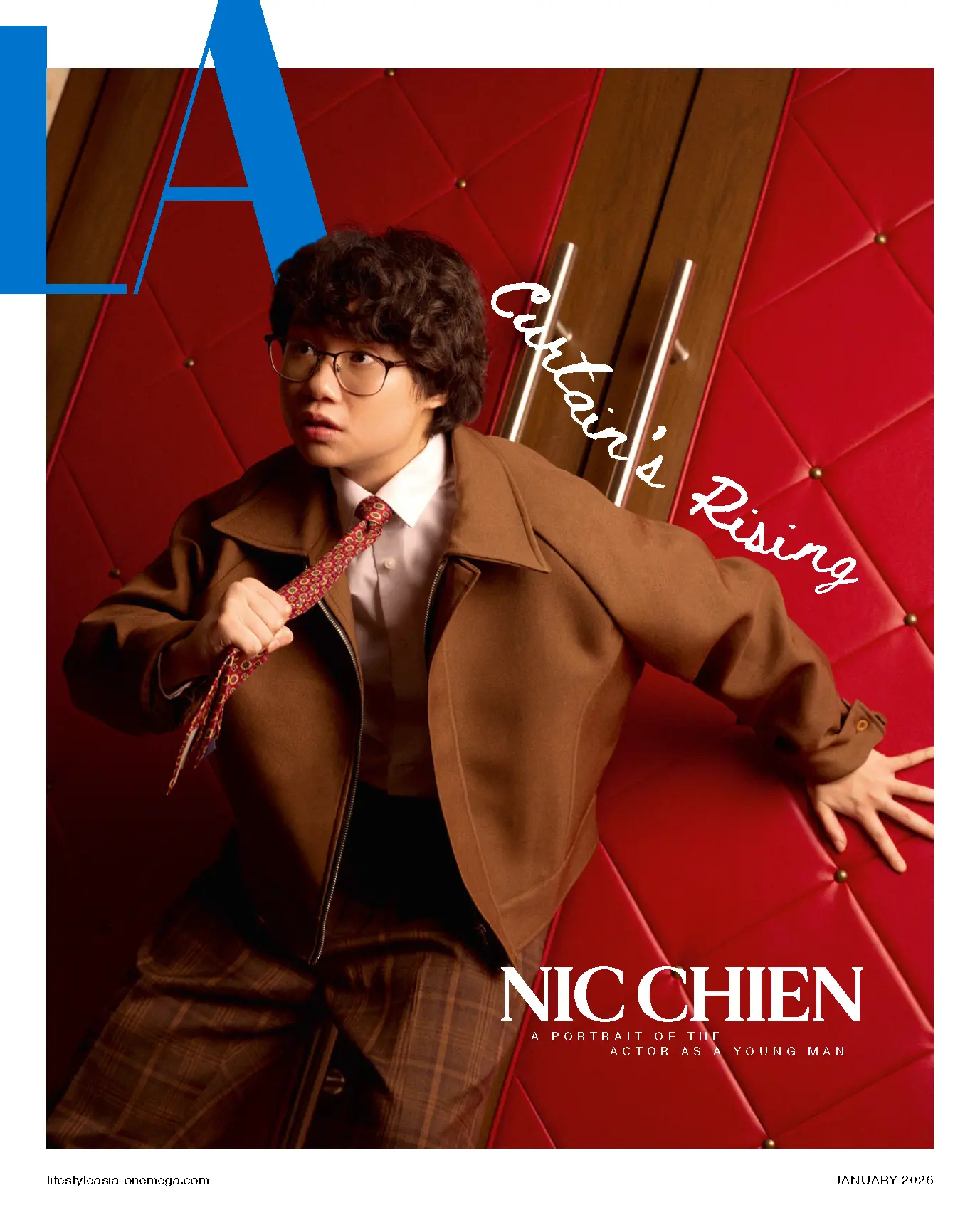

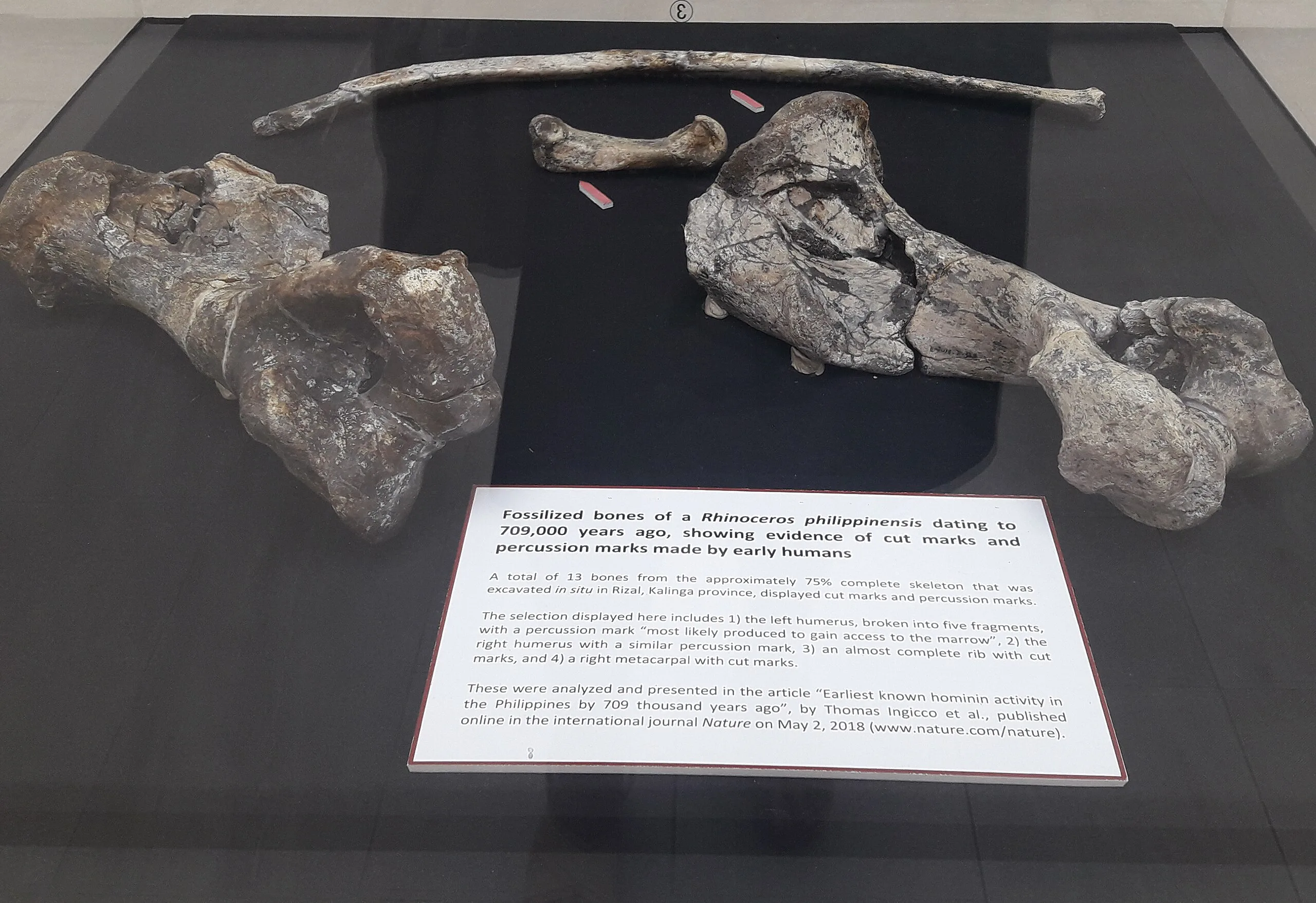

Philippine rhinoceros (Rhinoceros philippinensis)

We know Taguig’s Fort Bonifacio as one of Metro Manila’s busiest business and lifestyle hubs, but once upon a time (long before it even had a name), it was one spot where Philippine rhinoceros (Rhinoceros philippinensis) went about their business. Yes, you read that right. Besides Cagayan and Kalinga, Fort Bonifacio was also home to this small, extinct species of endemic rhino.

The first fossil evidence was found in Laya, Cagayan in 1936, according to the National Museum of the Philippines (hundreds more have been found since then). Another fossil was unearthed beneath Fort Bonifacio in 1965, preserved in a thick volcanic ash deposit, and composed of a “right upper jaw with two well-preserved molars and one broken one.” Then in 2013, a team led by Dr. Thomas Ingicco from the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle found a nearly complete skeleton of the species in Rizal, Kalinga Province.

Some of the fossil evidence is as old as a million years, while others date back to around 700,000 years ago. Interestingly enough, certain specimens have markings that indicate bludgeoning and cutting, suggesting that they lived in tandem with the Philippines’ early humans around the same time.

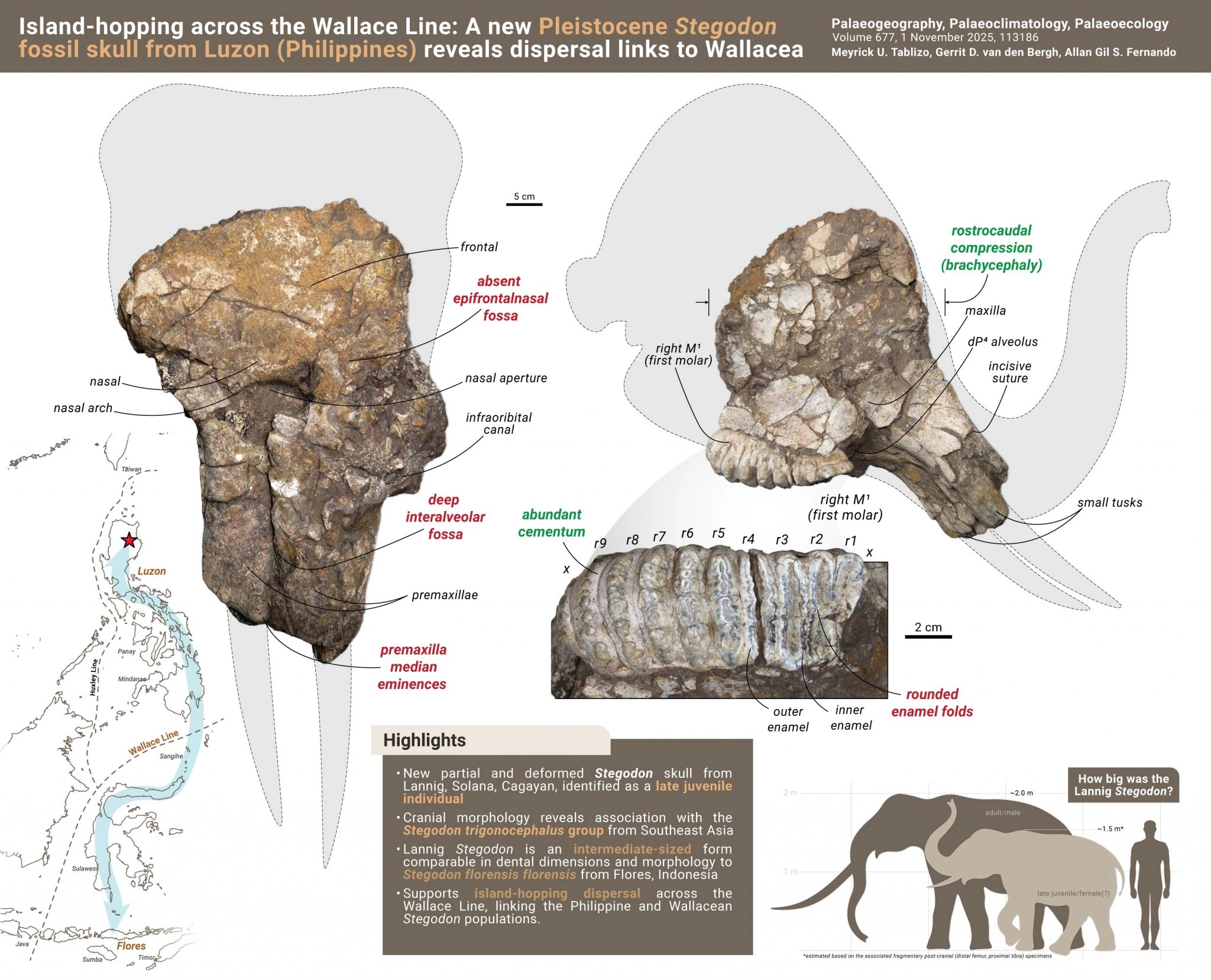

Stegodons (Stegodon luzonensis)

The name sounds like a dinosaur, but Stegodons are more like today’s elephants. Scientists estimate that a fully-grown Stegodon was just a little smaller than your average Asian elephant, and lived in other parts of Southeast Asia, including Indonesia. These animals were grazers with low-crowned teeth, as the National Museum of the Philippines explains, and tusks that grew close together, which meant they needed to rest their trunks sideways over one of these tusks.

Even cooler, research suggests they were incredibly powerful swimmers, capable of traversing the open seas and “island hopping” (since nothing was connecting our land masses at the time).

Animal skulls are generally fragile (usually the first ones to get crushed or destroyed), so finding one of a Stegadon is rare; most scientists work off fragments, as the UP Diliman College of Science (UPD-CS) details in a report. It wasn’t until 2013 that paleontologists from UPD-CS and the University of Wollongong in New South Wales, Australia, found the first ever fossil skull of a Stegodon “teenager,” which is roughly a million years old. Though their findings also suggest that there were different kinds of stegodon in the country: a larger one, and a smaller “dwarf” type.

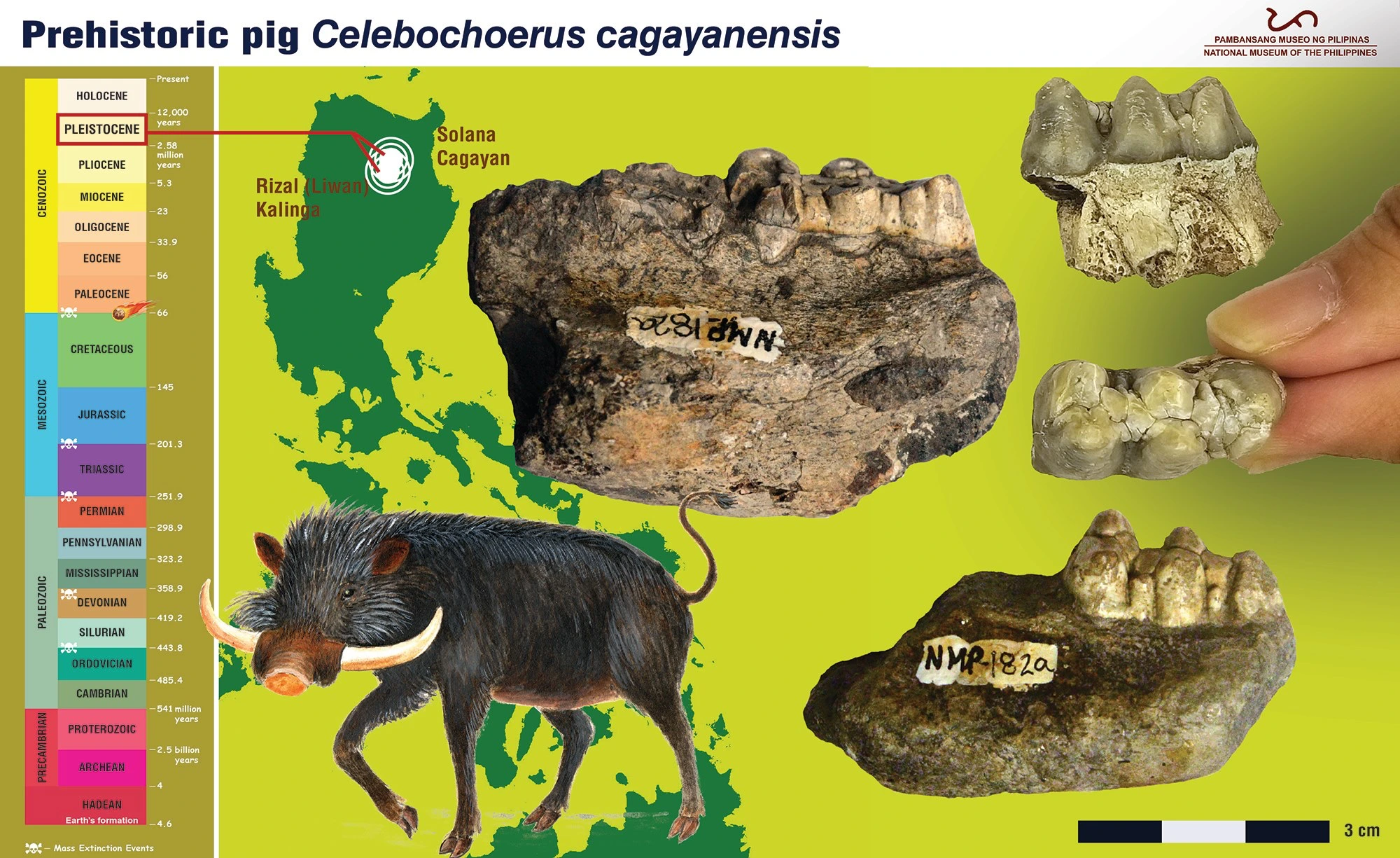

Cagayan Pigs (Celebochoerus cagayanensis)

The Celebochoerus cagayanensis doesn’t have a common name, though some refer to it as the “Cagayan pig,” based on the location where many of its fossils were found. These wild pigs sported incredibly large tusks and lived on the island of Luzon around 800,000 years ago. The Philippine species differs from that of a similar one found in Sulawesi, Indonesia, differentiated by “enamel bands” on its upper canines, as the National Museum of the Philippines explains.

The ancestors of these pigs are said to have traveled to the Philippines from Taiwan before branching out and migrating to Sulawesi. While this particular pig is now extinct (scientists suggest it may have been due to increased competition), a part of them lives on through its distant cousin: the Visayan warty pig, which currently holds a critically-endangered status.

READ ALSO: Get To Know The Rare Philippine Animals On Our Polymer Banknotes

Giant Cloud Rats

“Giant cloud rats” is actually a common umbrella term for multiple species of big rodents, many of whose remains have been found in several caves across northern Luzon. Research from the University of the Philippines and the Journal of Mammalogy suggests three species of these creatures lived alongside the oldest human species (Homo luzonensis). They were endemic species as well, weighing around a kilogram each; they were big enough to actually be hunted and eaten by our ancestors (yum). Their diet mainly consisted of leaves, seeds, and buds, and they usually climbed and lived on trees, as Marian Reyes, a zooarcheologist at the National Museum of the Philippines, explains. These rodents were even given local names: buot and bugkun.

With their fluffy tails and “striking fur colors,” as Reyes describes, these rats were believed to have survived “profound climatic changes from the Ice Age,” adds Philip Piper of the Australian National University. Scientists are still uncertain about the reasons behind their extinction, though dating suggests they might’ve been affected by the introduction of dogs, pigs, and macaque monkeys as agricultural societies began to develop in the country.

Of the three species, the largest was Carpomys dakal (“dakal” meaning “big” in several Philippine languages), the second smaller one being Crateromys ballik (“ballik” being “small” in the Dupaningan Agta language), and the smallest being Batomys cagayanensis (named after the archeological sites where they were found).

Luzon giant tortoise (Megalochelys sondaari)

Yes, there’s a common pattern here: the Philippines had its fair share of giant animals, including the tortoise Megalochelys sondaari. The reptile inhabited the country around 2.58 million years ago (the Early Pleistocene), its first fossils discovered in Rizal, Kalinga in 1971, then in San Juan, Tuao, Cagayan in 1976—though scientists were only able to identify it in 1989, when more fossil pieces were discovered in Antipolo City.

These species of Megalochelys tortoises lived all across Asia, though the biggest is the Megalochelys atlas from India, Myanmar, and Thailand, whose carapace (top of its shell) could reach a size of up to two meters lengthwise, according to the National Museum of the Philippines. Still, the Megalochelys sondaari was pretty impressive in scale, with a carapace that could grow up to 70 to 90 centimeters in length. Scientists can’t say for sure how these tortoises disappeared, though they suspect it might’ve been due to the arrival of early hominin, Homo erectus, who overexploited or hunted the animal.

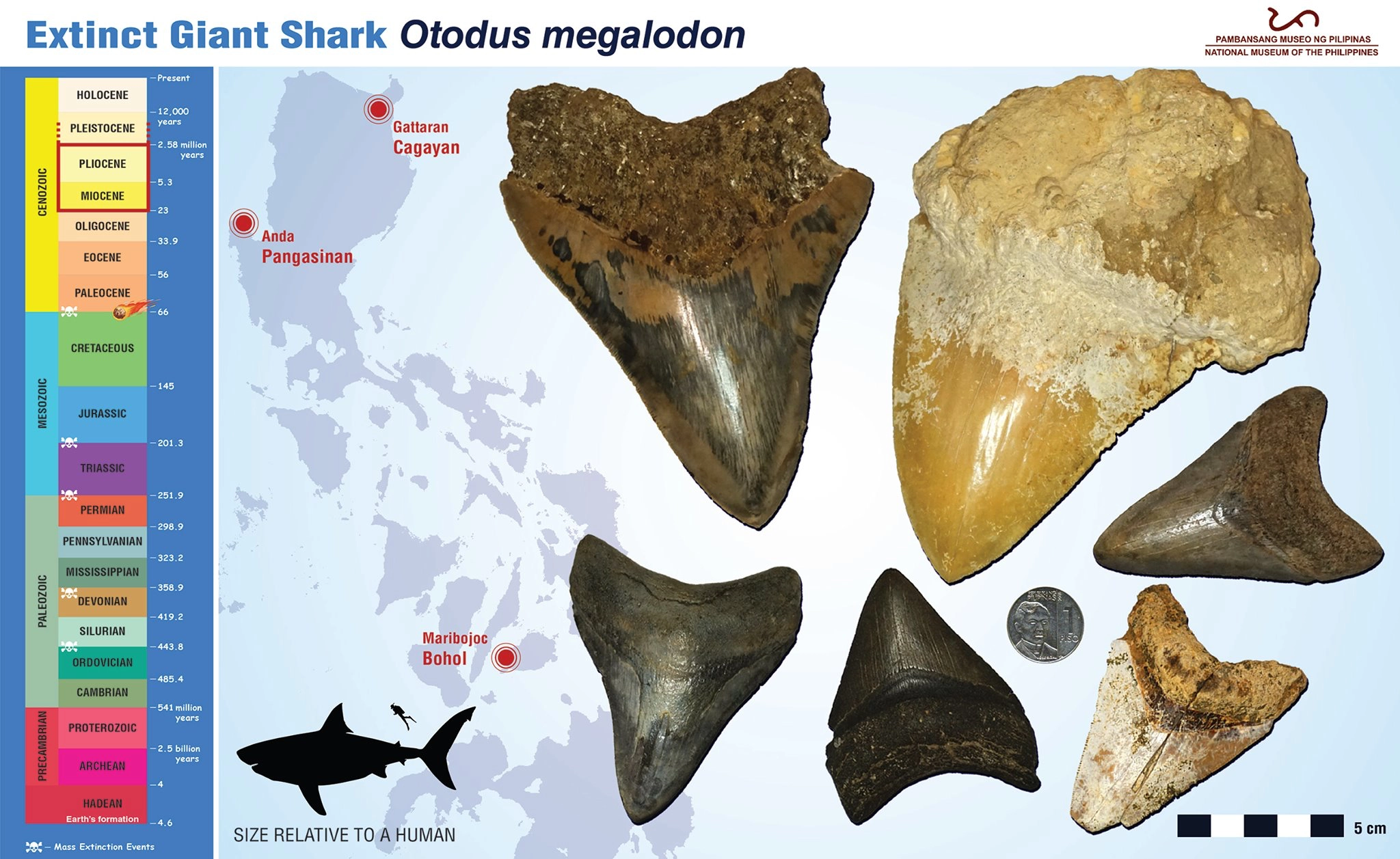

Megalodon (Otodus megalodon)

Old Brucie from Jaws would look like a piranha compared to your usual Megalodon: the largest shark and fish to have ever existed, measuring 15 to 18 meters in length. To put it into perspective, Bruce in the film was roughly 25 feet long—just a little more than seven meters. We should be thankful we never had to swim in an ocean rife with these creatures, though around 20 million years ago, these sharks were lounging around our islands and feasting. Because Megalodons, and most sharks, are made up of mostly cartilage (that rubbery material in our noses and ears), most of their remains rarely survive. We only have their huge teeth as evidence of their existence. Several fossilized Megalodon teeth were found all around our country, as the National Museum of the Philippines explains.

Some teeth found in Pangasinan measured 9 by 10 centimeters (grab a ruler and see how scary that is); while two other specimens uncovered in Gattaran, Cagayan, are around 3.6 to 2.6 million years old, one measuring 11 by 12 centimeters and another being eight by eight centimeters. Another tooth found in Maribojoc, Bohol, measured 7.6 cm by 6.5 centimeters. So how did such a huge apex predator disappear? Reasons are unclear, but scientists suspect it might’ve been the diversification of competitors (like the great white shark), or a cooling climate that forced its main source of food (whales) to travel to cold Antarctic waters that it couldn’t inhabit.

Why Don’t We Have Dinosaurs?

Now onto the bigger question: why don’t we have any dinosaur fossils?

Micropaleontologist and biostratigrapher Dr. Marietta M. De Leon explains in a 2005 article that the simplest answer is this: the Philippine islands didn’t exist when dinosaurs were alive. What would become the Philippines was still deep underwater: the archipelago only emerged during the Tertiary period (around 65 to 1.64 million years ago), a few million years after the dinosaurs had already gone extinct.

Still, the absence of discoveries doesn’t mean fossils are impossible. Dr. De Leon notes that certain areas—particularly Palawan and Mindoro—may still hold potential. After all, the Philippines’ more than 7,000 islands originated from different parts of the world, including regions like Mainland China, where dinosaur remains are abundant.

She also points to New Zealand as an example: once thought too isolated and too small to have ever hosted dinosaurs, it was later found to contain fossils of Mesozoic reptiles. Like the Philippines, its islands were formed from fragments of other ancient continents, some of which did see dinosaurs roam.

Whether or not we eventually find these fossils, we can at least say our country has long been a colorful melting pot of equally amazing creatures.