A fairly entertaining fanfiction wet dream with a TikTok-ready aesthetic, the latest Wuthering Heights adaptation manages to stand on its own two feet, though not without wobbling (and tumbling) along the way.

Warning: This piece discusses an opening scene, certain creative executions, and characterizations within Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights,” but contains no other spoilers.

Lifestyle Asia recently had the pleasure of catching an advanced screening of Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” (yes, I’m keeping the infamous quotation marks—we’ll get to that later) at the newly renovated Greenbelt 3 cinema. I was burning with curiosity from the sheer volume of pre-emptive vitriol that erupted with the release of its “first look” images and trailer. To be fair, every book adaptation attracts its share of flack from devotees, and the people who adore Wuthering Heights really, really, truly adore it.

I can’t claim to be the novel’s most ardent fan, but I do find it a compelling and complex gothic work (far ahead of its time), one that’s been reinterpreted endlessly and misunderstood just as often. And because it doesn’t occupy the most precious corner of my heart, my vantage point is admittedly a more forgiving one.

Besides, an adaptation, whether loose or rigorously faithful, is an act of translation. It will always be an approximation of the original, a filmmaker’s rendering of their own comprehension—and that understanding will never satisfy everyone. (I will say, however, that Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice has come very, very close to perfection.)

With that in mind, this review will mainly focus on how the film stands on its own, before delving into the merits of its conversation (or lack thereof) with its source material.

READ ALSO: On The Never-Ending Discussion On Actresses And Age, But This Time It’s Valid

Is It An “Adaptation,” And Does That Matter?

Fennell’s film can hardly be called an adaptation, at least not in the strictest sense. So her move of eliminating the weight and accountability of fidelity to the text by enclosing the film’s title in quotation marks makes sense.

“You can’t adapt a book as dense and complicated and difficult as this,” she admits in an interview. “I can’t say I’m making Wuthering Heights. It’s not possible. What I can say is I’m making a version. There’s a version that I remembered reading that isn’t quite real. And there’s a version where I wanted stuff to happen that never happened.”

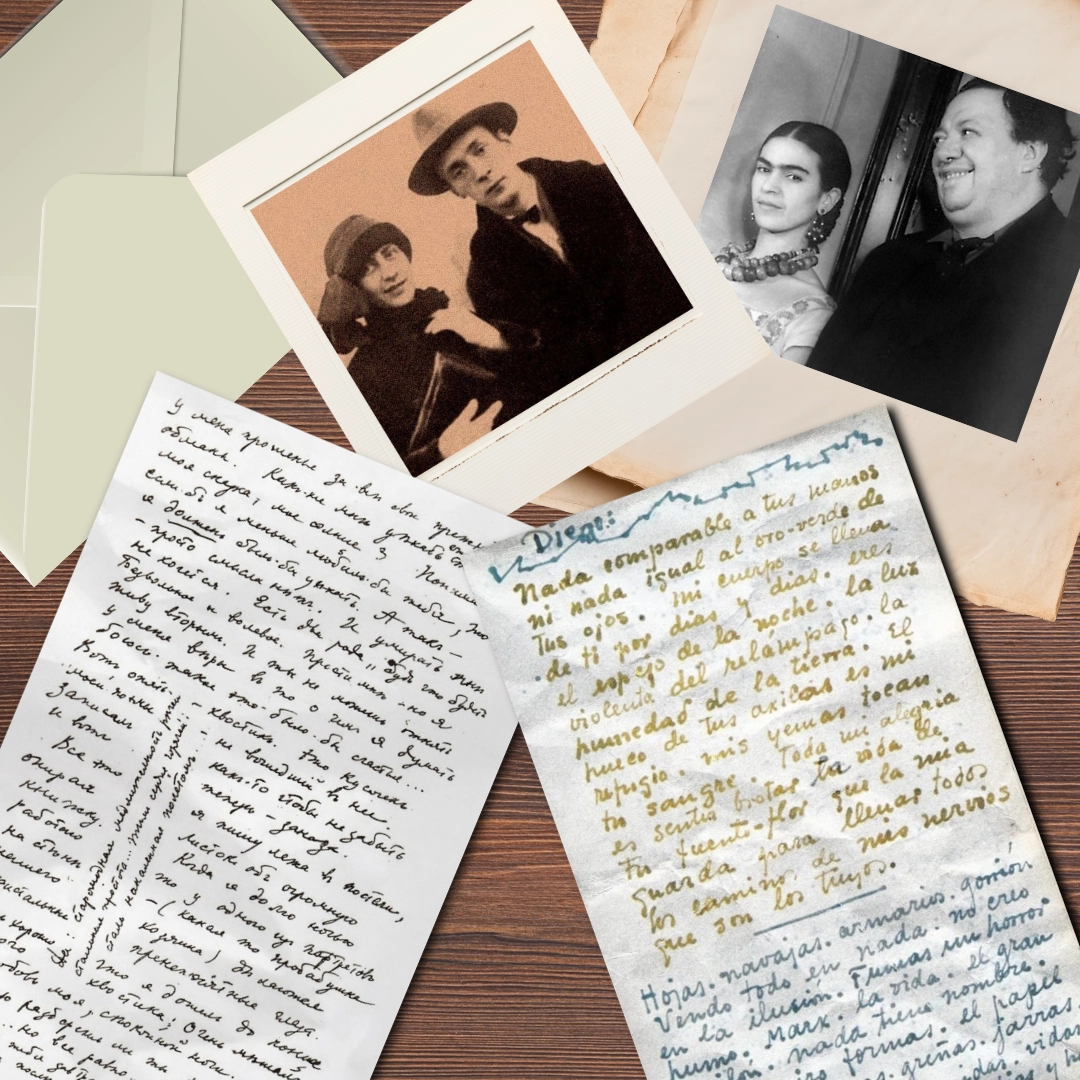

Fair. And if we’re being completely honest, no film has ever quite stuck the landing when it comes to adapting Emily Brontë’s work. Not because they were terrible, but because each carried its own merits and faults, its own gaps and omissions.

Most cinematic iterations prefer cutting out the other half of the novel that focuses on the second generation bloodline of Catherine (Cathy) Earnshaw and Heathcliff. William Wyler’s 1939 film smoothened out the unsettling elements that define the book, opting to transform it into a Golden Age of Hollywood romance; and again, it was a great film, it just wasn’t the entirety of Wuthering Heights. Even the more recent 2011 adaptation by Andrea Arnold completely cut out that latter part of the novel, though it’s the only one to ever represent Heathcliff as he was originally depicted in the book: a person of color, likely Romani or a “lascar” (referring to sailors of Indian or Southeast Asian blood), played by Black actors (Solomon Glave as a youth, James Howson as an adult).

This is a long-winded way of saying that no one has ever really “understood the assignment,” as we put it today. What they’ve done instead is create works that tease out a different facet of the text. Wyler’s adaptation managed to retain a strain of gothic melodrama, folding in the novel’s supernatural currents as best it could (still fluffy, but nothing unbearably saccharine). The 2011 version was admittedly languid and sparse in dialogue (hardly the vehicle for the feverish poeticism of Brontë’s prose), but there was a wild and primal quality to it that heightened the novel’s dark, untamable atmosphere.

The Fennell-ification Of Wuthering Heights

Before I get into the nitty-gritty and pitfalls, let’s begin with what did work, once I switched off the part of my brain that insists on some semblance of fidelity at all times. One of those things is the visuals, across the board. Were the fairytale-esque costumes by Jacqueline Durran faithful to the text? Absolutely not. But historical accuracy is already in shambles here, so we might as well abandon that metric altogether. What they were, however, was stunning. Even the more outlandish, borderline gaudy pieces were eye-catching, reveling in their excess.

Suzie Davis’ set design is just as beautiful, moody and dollhouse-like. Other than the sprawling cliffsides, there’s something uncanny and deliberately artificial about it all, yielding backdrops that oscillate between glamor and unease. Walls mimic skin, hallways glow a bloody red, tea parties unfold in pastel rooms, and moments of sex are framed by images of dampness and heaving motion. Linus Sandgren once again delivers cinematography that dazzles, keeping viewers thoroughly impressed as a welcome distraction from the narrative mess.

Fennell has always privileged style, oftentimes to the point where substance takes a detour. Like Saltburn (arguably even more so), “Wuthering Heights” feels like it was made for TikTok fancams, more a Pinterest mood board or intoxicating evening fantasy than anything else.

Some Drastic Character Transformations

Like those before her, Fennell chooses to focus on the intense relationship of the story’s star-crossed lovers. Her Wuthering Heights is perhaps the loosest adaptation to date: she streamlines the plot, omitting most of the secondary players and focusing almost exclusively on the central, doomed couple and select supporting figures, collapsing roles that were once dispersed across multiple characters into single presences.

For instance, gone is Cathy’s violent, drunkard brother Hindley, the primary source of Heathcliff’s abuse and the eventual target of his calculated revenge in the novel. Instead, he’s integrated into the originally benevolent Mr. Earnshaw (Cathy’s father), who stands as an almost Jekyll and Hyde-like figure in the film (played by Martin Clunes).

Nelly Dean (played by Hong Chau)—the novel’s narrator, servant, and fly on the wall—shifts from a comparatively neutral, maternal observer into a figure with an entirely new melancholic backstory, one that fuels soap-operatic motives and actions, and positions her less as witness than as active plot catalyst within Fennell’s film.

Cathy is played by Margot Robbie, and while the casting initially raised eyebrows due to her age, she commands attention with a performance that foregrounds something many adaptations soften: the protagonist’s cruelties. Cathy is no saint. If anything, she’s the other volatile half of this toxic power couple. Robbie brings an edge of petulance and viciousness that, in certain ways, feels truer to Brontë’s Cathy than some previous interpretations.

The younger Jacob Elordi takes on Heathcliff, now carrying the distinction of first-time Oscar nominee for Frankenstein. Which… is quite the shame, because Fennell’s screenplay doesn’t fully capitalize on the depth we know he’s capable of as a performer. In fact, it’s Heathcliff who suffers the greatest betrayal at the hands of the story.

50 Shades Of Heathcliff

Heathcliff, once again, is white. Regardless of where you stand on colorblind casting, this particular choice (rooted, as Fennell has said, in her original “vision” of him when she first read the book) erases a key dimension of the story. Heathcliff’s mistreatment isn’t driven by class alone; it’s, in large part, fueled by bigotry. To flatten that reality is to blunt one of the novel’s sharpest edges.

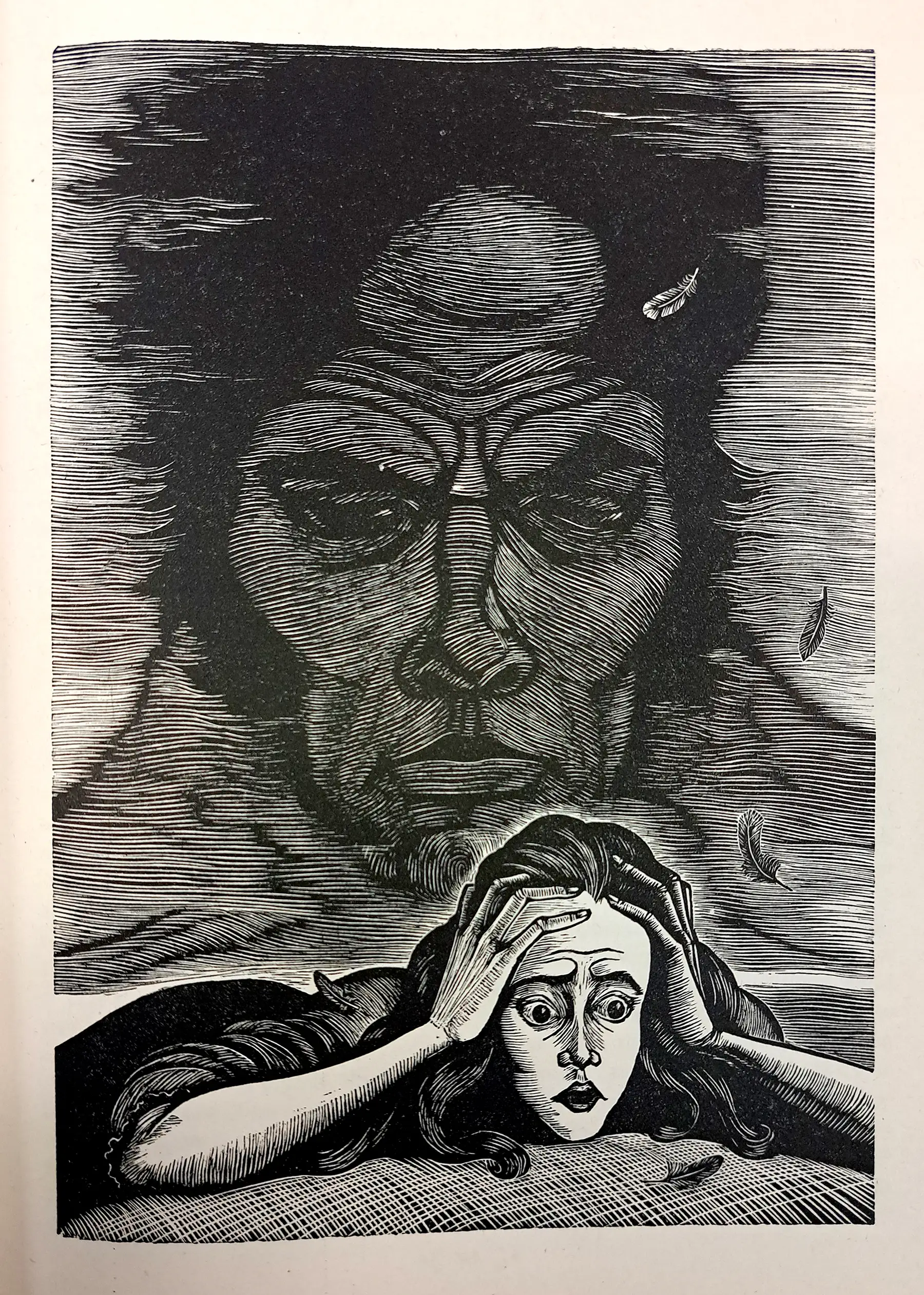

So we move on to who Heathcliff is meant to be: a man driven to extremes by years of maltreatment, someone who obsessively clings to the one woman who has ever truly understood him and offered him a deep, genuine love. His later acts of depravity and violence are not born in a vacuum, but emerge from a cycle of brutal abuse that he survives and perpetuates.

For very, very brief flashes, Elordi’s Heathcliff almost gets there. Almost. There’s a glimmer of Brontë’s leading man—a suggestion of that feral, wounded intensity—but it never quite manifests. What we’re given is a sweaty, shirtless, brooding figure fashioned after the bodice-ripping imaginations of countless teens and pulp romance lovers.

Personally, I don’t mind that he’s sad, hot, and horny, but my gripe is that he isn’t much else. It’s not that Fennell neglects to depict the abuse Heathcliff endures; she does carve out space for it, but she never quite commits to the unrelenting horror or its aftermath. The suffering feels gestured at rather than fully inhabited. Viewers that are after the rush of sex appeal and erotic charge might even love it. But it ultimately flattens what was once a more layered, psychologically knotted character into an edgy heartthrob. If that’s not your thing, consider this your warning.

There’s an S&M thread woven in the film’s many, many sex scenes (people have taken to saying it’s the fourth installment in the 50 Shades trilogy), but it rarely goes beyond surface provocation. It toys with desire and taboo without ever fully interrogating them, even when you find yourself hoping it will. The Charli XCX soundtrack, with its foreboding synths and thumping pop beats, feels distractingly anachronistic. And yet, within the context of all this self-indulgent fanfiction-esque smut, it’s oddly fitting.

Treat It As Its Own Thing On Valentine’s Day

Strangely enough, despite all its extravagance and outlandishness, there’s a restraint running through the new movie. I kept wishing it would go further with all that yummy icing layered over a middling cake. Push the grotesque even harder. Take the “forbidden” love and tension it clearly wants to wring from Cathy and Heathcliff, and turn the madness dial up. Don’t hold back. If S&M is what you’re aiming for, let audiences stare at unhinged perversion and degradation. Yet every time it teeters on the precipice, it pulls back.

The opening scene—in which a frenzied crowd cheers and revels in debauchery during a hanging, rough music blaring as a body swings in squeaky wooden apparatuses that sound disconcertingly sexual—launches the film with a macabre, chaotic intensity it should’ve fully embraced. Instead, it merely flirts with transgression and boldness, never quite sustaining either.

All that said, was I entertained? Yes, actually. I didn’t long to leave my seat, and even found myself silently giggling over scenes that were clearly Elordi fanservice. “Was this in the book?’” a friend I watched it with (who actually has read the book) asked jokingly. No, reader, Heathcliff doesn’t have steamy sex with Catherine in the novel, nor does he take off his shirt to reveal glistening pecs and chest hair (spoiler alert). I suppose Fennell, and quite a few readers, wished he did, and that’s the crazy fantasy this film tries to bring forth. It’s a fairly good time at the movies if you show up with zero expectations beyond wanting to be occupied for a couple of hours. I just wish Fennell had ditched the title entirely and leaned into framing this as its own hideous, intriguing creature.

Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” is clearly engineered as a strategic, box-office Valentine’s release, buoyed by its sanitized, more palatable rendering of Cathy and Heathcliff’s love. We can’t fault her entirely for that: she’s hardly the first filmmaker to sand down Brontë’s rough edges. It’s a spectacle best experienced if you’re willing to surrender to it and ride the waves of its chaos rather than fight them.

Photos courtesy of Kinorium (unless specified)