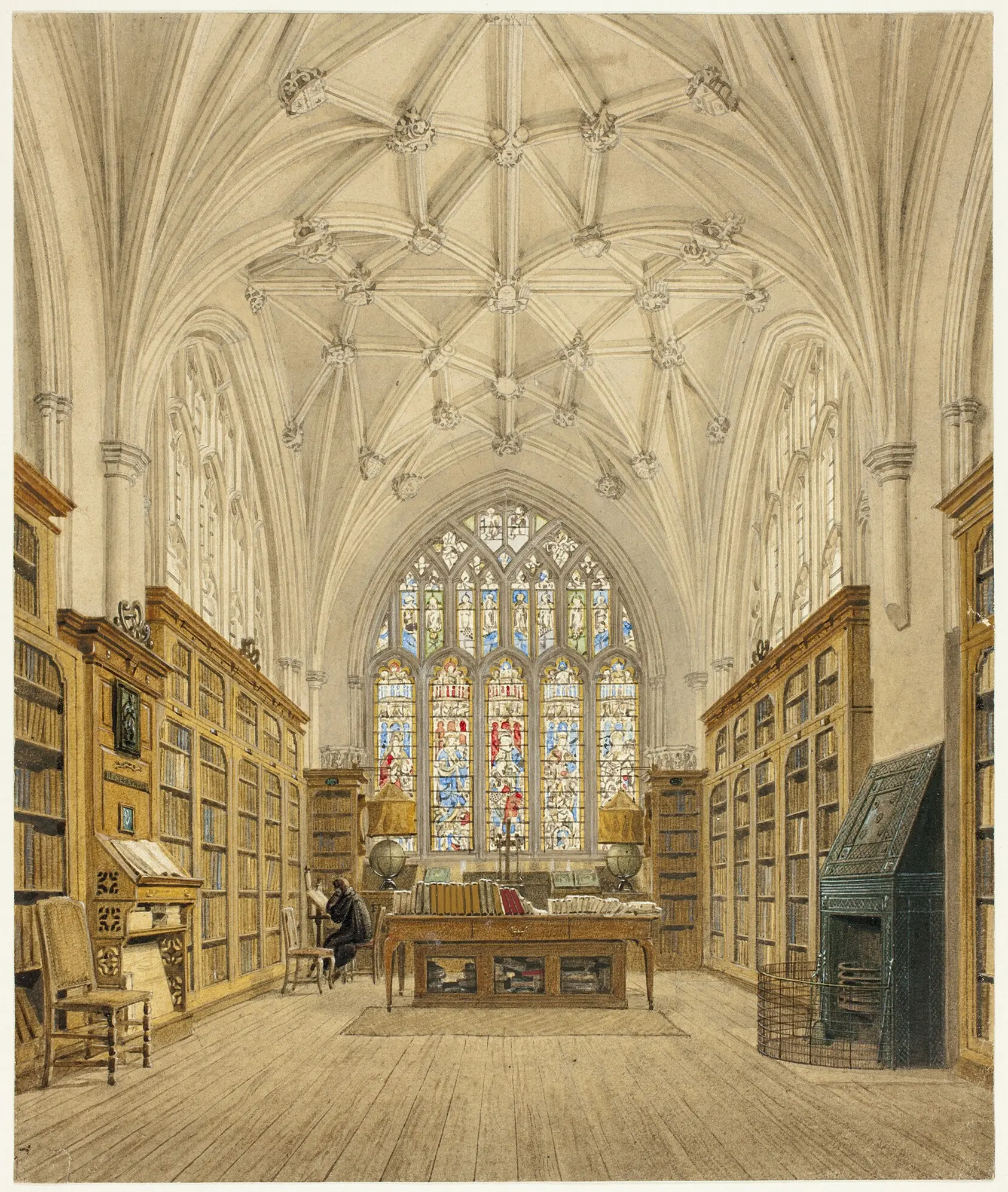

Quiet, steadfast, and perhaps the last bastions of reliability in today’s world of misinformation and AI-driven systems, libraries are far more than places that hold books.

When I try to recall some of the fondest memories of my grade school days, most of them were spent in our school’s small but welcoming library. White tiles, brown shelves, the smell of wood and paper, soft couches, and pillows. Well into adulthood, I still find myself dreaming about these images and sensations on some nights. For a young girl who didn’t know much about the world, the library was a space of both comfort and possibility. It mirrored the effect of the books it held, carrying me through the stories and knowledge of hundreds of minds without ever leaving that safe haven of quiet. Granted, it was a private space funded by tuition money, but the significance is just as true for public libraries —even more so, given how essential they are to the communities they serve.

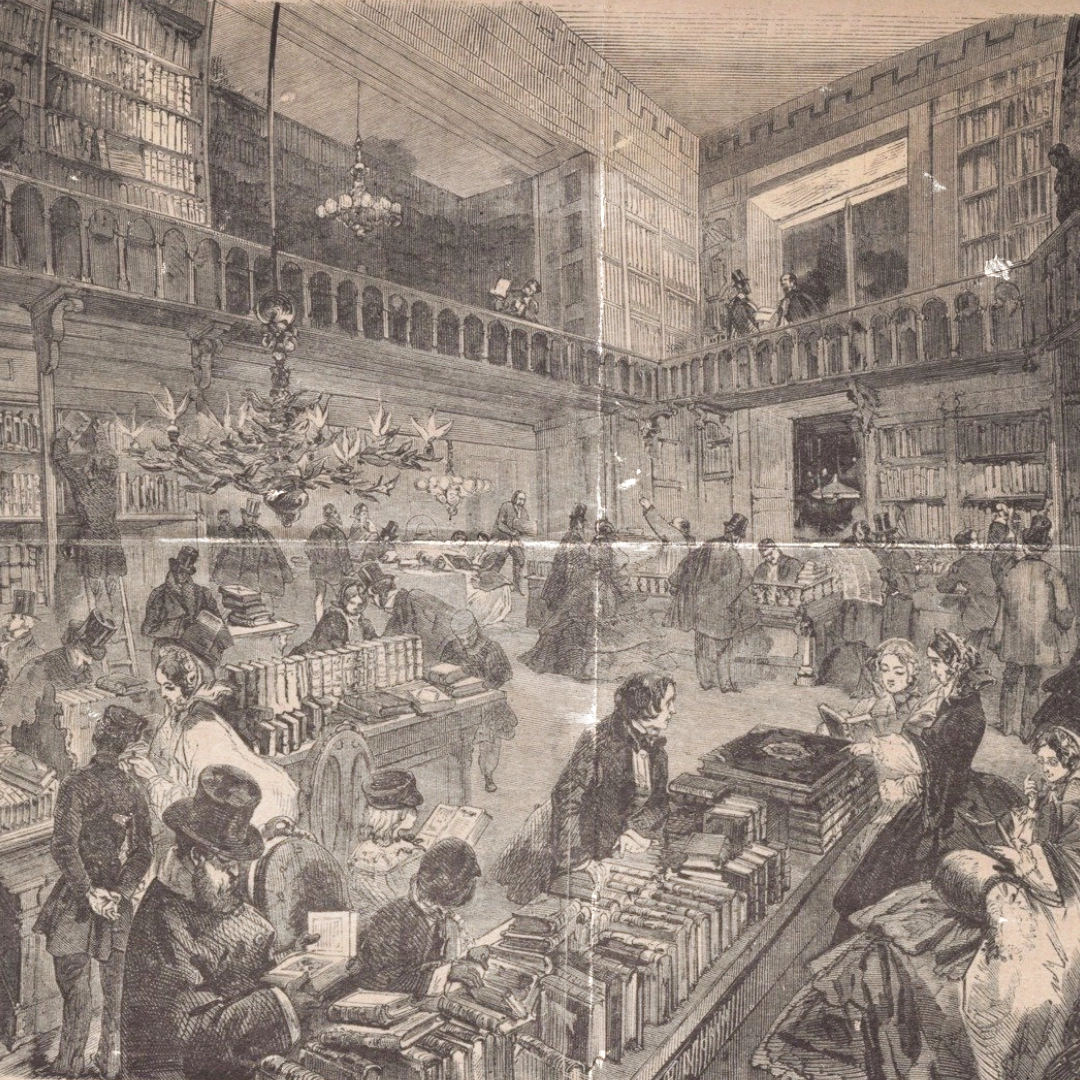

Throughout the decades, especially since the rise of the internet, the role of libraries has often been called into question. In places where fascist or authoritarian regimes impose strict censorship, their importance and security have never been more crucial. Anyone whose life has been touched by a library, even in the smallest ways, knows that they’re far more than physical spaces, though they’re still too often reduced to the image of old librarians shushing patrons or dusty shelves.

So why, exactly, do these places matter when you can just type a question into ChatGPT and be done with it?

READ ALSO: When Everything Is Short, Does It Still Pay To Linger?

An Unparalleled Third Space

You can say whatever you want to defend the superiority of the internet and AI, but there’s one thing these digital tools cannot provide: a “third space” for anyone who needs it. For those unfamiliar with the term, it refers to a location that’s neither home nor workplace, but a place where one can relax, socialize, and build community. Libraries can certainly serve as workplaces for students and professionals, but that’s only a fraction of the bigger picture, and this versatility is exactly what makes them unparalleled third spaces.

Over the years, they’ve evolved to host all kinds of communal activities, from speed dating to book clubs. They remain peaceful, inclusive points of convergence for people from all walks of life. In these zones, children experience the joy of being read a story aloud; a teen who can’t afford all the novels in a fantasy series can simply check them out for free; a mother might rediscover a book of nostalgic recipes she thought lost to time; and lifelong learners gain access to vast amounts of human knowledge, free of paywalls or barriers.

I recall the hushed conversations I shared with grade school classmates over a wooden table in our library, flipping through a gigantic coffee-table book compiling famous artworks from around the world, each of us pointing out details we found funny or weird (the many butts present in Hieronymous Bosch paintings were particular favorites).

I remember slow afternoons when classes ended early, the days of rushing to the library, lying on bean bags, and devouring novels about goddesses, princesses, and wizards. Reading day was always fun, with librarians offering lollipops for every book we borrowed and, as a treat, letting us check out three books instead of the usual two. Computers were there for research, but we sometimes got away with playing dress-up games, much to the chagrin of the library’s custodians.

It was the library—and, of course, the English teachers who worked tirelessly to make school a little more bearable for the wandering minds of their wards—that instilled in me a deep love for knowledge and reading. These may sound like the cliché ramblings of a nerd, and maybe they are, but I get a bit misty-eyed thinking about a reality where I was never surrounded by this kind of environment.

Somewhere out there is a kid, an adolescent, a college student, a full-grown adult, searching for answers to burning questions and companionship through the words of the many humans who came before them. A book, a self-education, could change the entire trajectory of a person’s life for the better. What would the world be without that sort of community and freedom?

What The Internet Just Can’t Teach You

I’ve heard a few arguments—some explicit, some implied—about the library’s place in today’s society, many of which revolve around the sheer volume and accessibility of information. With the rise of AI, all the knowledge and data on the internet is at your disposal, compressed and regurgitated with a few commands. And really, there’s a grain of truth to that. You can access Google or ChatGPT anytime, from anywhere with Wi-Fi, on any device. As a writer, I spend most of my time researching through a browser.

“Going to the library” just isn’t something people can do on a whim, especially if they lack the resources to travel to one or need answers immediately. In the Philippines, where most of the population grapples with a failing educational system and the underprioritization of public infrastructure—including libraries, which are often considered last in line behind projects like flood control (even those are neglected)—this issue is compounded.

The digital landscape isn’t the enemy; in fact, it democratized knowledge to an unprecedented degree. Yet we should still consider the quality of that knowledge and the benefits of accessing it through other means, including tangible or physical ones. It’s also worth remembering that many public libraries provide computers and internet access, not just books.

Believe it or not, there are things the internet can’t teach or provide. Niche topics, for example, can’t be reliably answered by someone on Reddit saying, “Trust me on this.” ChatGPT can streamline information from countless online sources—but the accuracy of those sources still requires careful cross-checking at best, and at worst, some are outright misinformation.

“The explosion of information online hasn’t sidelined librarians. It’s only made them more essential at a time when too few of us know how to distinguish real news from the fake variety,” writes Jennifer Howard in her essay “The Complicated Role of the Modern Public Library.”

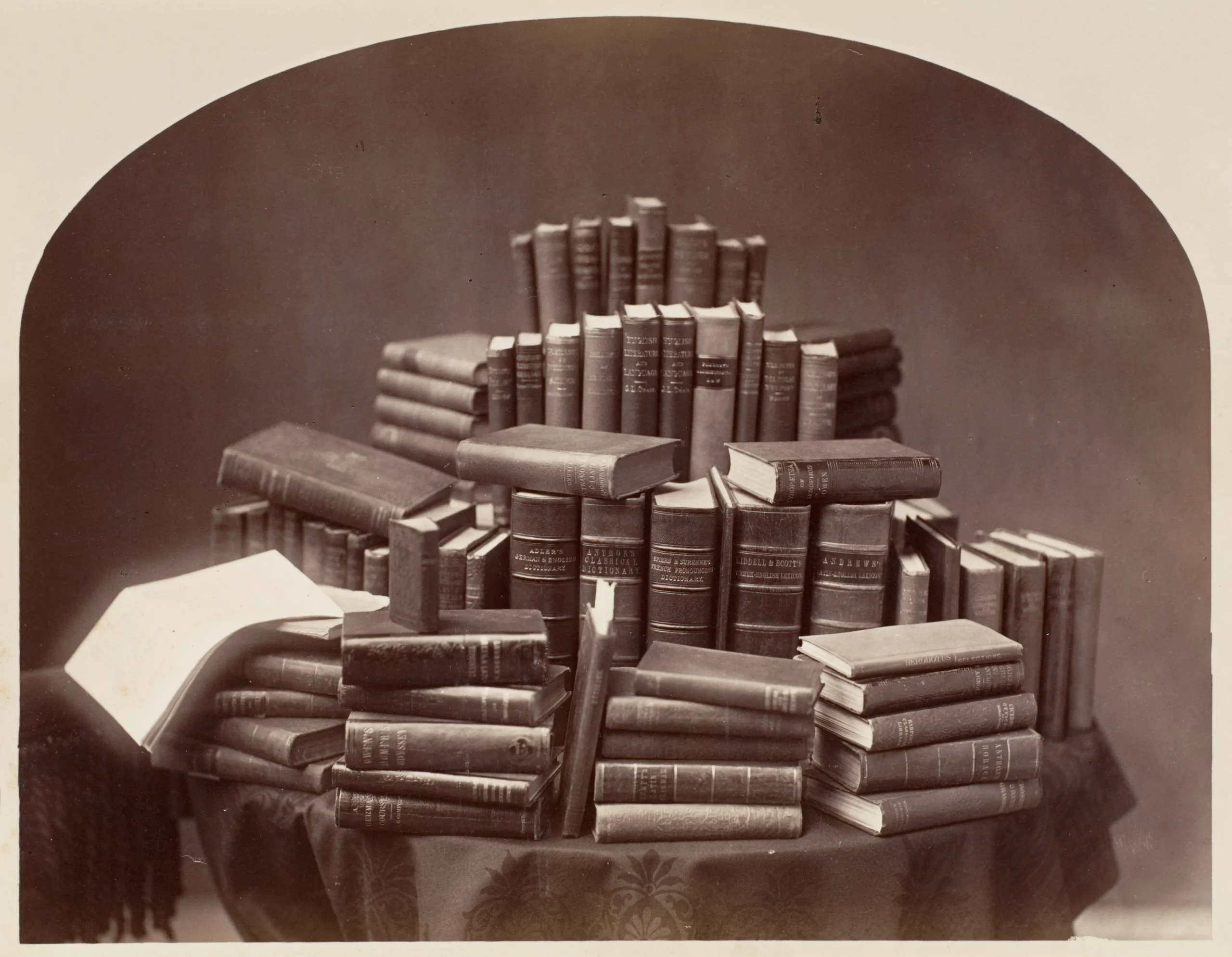

When I set out to write about the evolution of the barong Filipino in relation to our Philippine presidents, or the state of film restoration in the Philippines, what ultimately aided me were library books. Topics I once thought too specific or too obscure were all there in print. It was almost comical: me standing by the library counter or OPAC, thinking, “Surely they don’t have a book about this specific concern,” only to have a librarian—or the search results—confirm that they did indeed have exactly what I was looking for.

And in its typical analog fashion, a library teaches you to slow down and savor the act of searching for answers: looking through alphabetical lists, moving along the shelves to find the right book code or title, and delightfully stumbling upon books you weren’t searching for, but that you actually needed.

I can trust the information they present, for the most part. Unlike online posts, these works aren’t the products of someone casually sharing their opinion. Researchers, writers, and scholars spent countless hours conducting field studies, interviews, and reviews of related literature before having their work vetted by editors and published. Those are safety nets you rarely get in the process of sharing information on the internet. It’s not perfect, but it’s as close to the truth as we can get. And with libraries that work to keep their systems and collections as updated as possible, this is a priceless resource.

Libraries In Manila To Visit

And with all that said, you might be wondering: are there any good libraries in Manila? The answer is complicated. The Philippines, in general, is far behind other countries when it comes to providing comprehensive, high-quality public libraries (for reasons I’ve already mentioned in the last section).

Still, there are a few trying to do the good work, and more private ones that still remain accessible to the public. Here are a few you can consider visiting.

Quezon City Public Library

Quezon City’s public library, save for minor fees, is completely free and hosts a variety of activities for the public, alongside providing other resources like computers.

Location: Gate 3, City Hall Compound, Quezon City

Website: https://qcpl.quezoncity.gov.ph/

National Library Of The Philippines

Also free for public use, it features an expansive collection of Filipiniana materials, on top of spaces for studying and research.

Location: 1000 Kalaw Ave, Ermita, Manila

Website: https://web.nlp.gov.ph/

Ortigas Foundation Library

Hosts a collection of over 36,000 Filipiniana books, photographs, periodicals, and more, perfect for those into all things Philippine history.

Location: 2nd Floor, McKinley Parking Building (above Unimart Supermarket), Club Filipino Avenue, Greenhills Shopping Center, San Juan

Website: https://www.ortigasfoundationlibrary.com.ph/

Reading Club 2000

While not a library in terms of space, the Reading Club 2000 lets people take home books free of charge. It’s always open, situated by the ancestral house of its founder Hernando Guanlao. Everyone is welcome, and encouraged to do their part, like sorting books or giving some of their own in return if they can.

It’s a heartwarming spot that really opens itself up to whoever wants knowledge, regardless of their background, and has helped underserved members of the community gain access to information without demanding anything in return.

Location: 1454 Balagtas Street, Barangay La Paz, Makati

Website: https://readingclub2000.com/