This story of a boy who dared to dance has earned its place among 21st-century cinema’s most progressive works—challenging machismo and celebrating self-expression with quiet, powerful grace.

Warning: This piece discusses key themes and plot points of Billy Elliot.

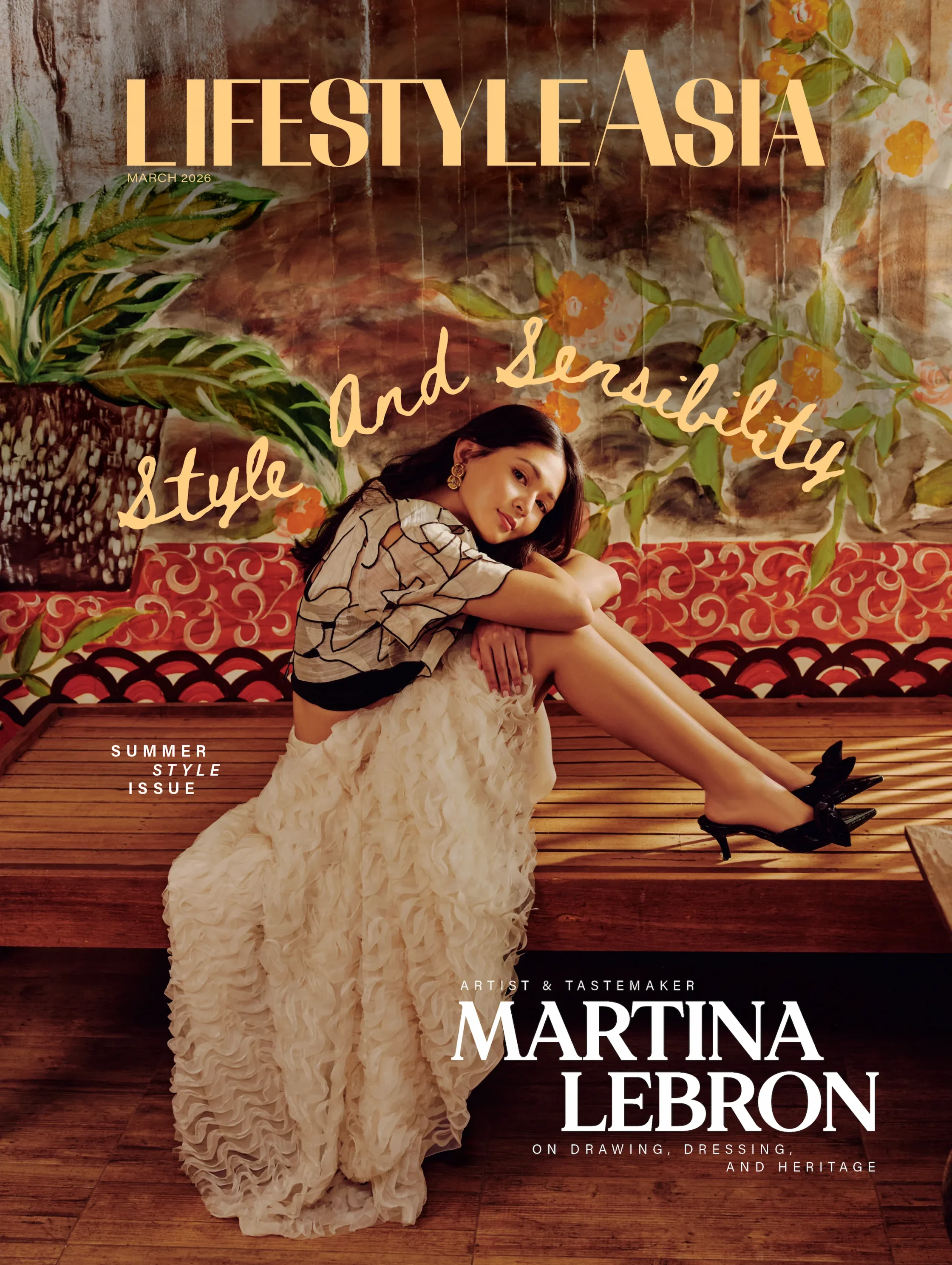

This year, Billy Elliot celebrates its 25th anniversary. Premiering in the United Kingdom in September 2000 and later in the United States on October 13, the film became a surprise box office success, earning over $100 million on a modest $5 million budget. It also became a critical darling, garnering three Oscar nominations (including Best Director for first-time filmmaker Stephen Daldry) and launching lead actor Jamie Bell into a career that has lasted for more than two decades.

Beyond the money and accolades, Billy Elliot endures as a landmark film, telling a powerful story about defying gender norms, embracing the transformative nature of art, and challenging the constraints of class. Its significance lies not just in its cinematic achievements, but also in the way it continues to spark conversations about identity, expression, and possibility across generations.

READ ALSO: The Challengers Effect: How One Sexy Tennis Movie Became A Cultural Obsession

Billy Elliot In Context

Billy Elliot is set in the fictional northern England mining village of Everington, but the struggles surrounding the protagonist and his family unfold against the backdrop of the real 1984 to 1985 coal strike, one of the defining moments in modern British history. The strikes began when Margaret Thatcher’s government moved to close 20 “unproductive” coal pits, threatening the jobs of 20,000 workers. In response, 187,000 miners launched protests that erupted into violent clashes, mass arrests, and widespread civil unrest. Billy’s father, Jackie (Gary Lewis), and his brother, Tony (Jamie Draven), are among those miners fighting for the cause. At home, the 11-year-old is left largely on his own—his mother had passed away, and his only companion is his ailing grandmother.

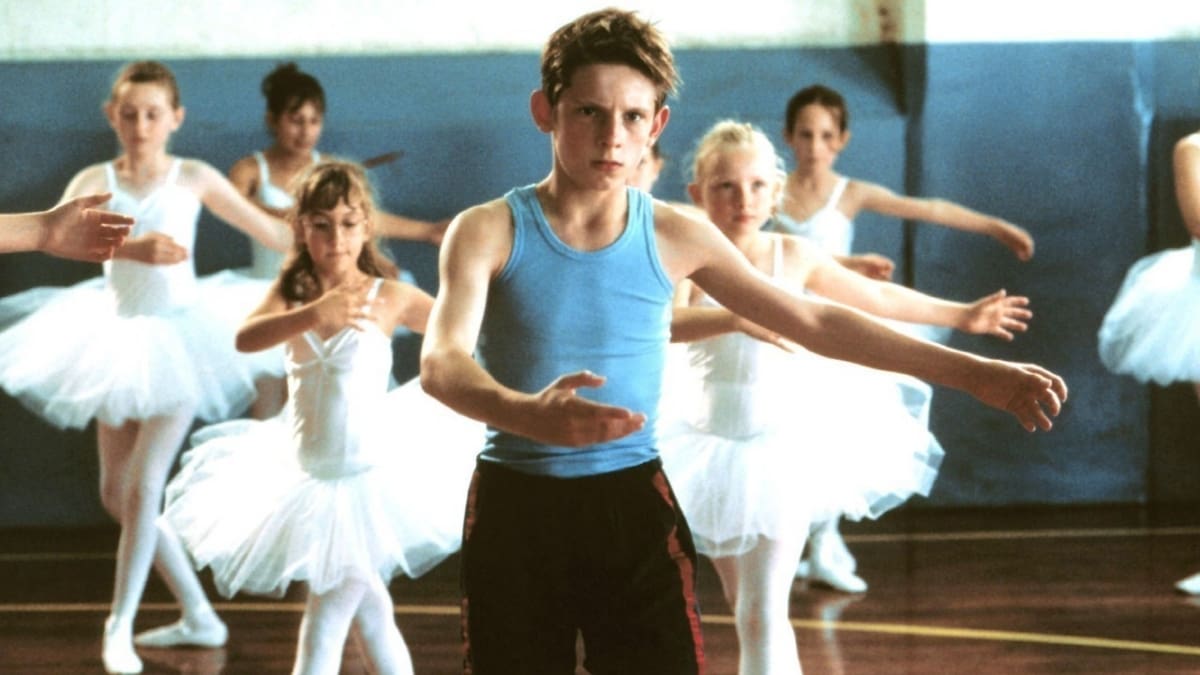

Despite their hardships, the family still enrolls Billy in a boxing class, a sport he has little interest in. However, he stumbles upon a ballet class in the very same hall as his boxing ring, and finds himself enraptured by the art form. What begins as a chance encounter soon becomes his lifeline, even if the newfound interest runs contrary to the very environment he was raised in—not just in terms of gender norms, but also socioeconomic circumstances. At the time, mining communities often encouraged their boys to pursue “masculine” activities such as boxing or football, while ballet was widely regarded as feminine, reserved for girls from elite families or at least the middle class.

Any boy who practices the art form risks being labeled a homosexual, and with the rise of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, Billy’s interest in ballet becomes an even greater taboo, prompting many to assume he’s gay and dismiss him as a “sissy.” Though it’s important to note that despite the film’s exploration of gender roles, Billy himself is not gay: he’s simply a boy who wants to dance and express himself in a world that has largely set him aside.

When Billy meets Mrs. Wilkinson (Julie Walters, in an Oscar-nominated role), the tough-talking teacher of the ballet class, she recognizes his potential and takes him under her wing, determined to nurture his talent despite the weight of their working-class backgrounds. She’s also the first character to truly treat Billy as a young man, rather than a boy, setting the tone for his growth.

Breaking Barriers With Music

As Billy continues to study ballet in secret, he realizes he doesn’t have to live inside the box his world has set for him. He isn’t destined to become a miner or remain in his hometown forever. Yet the filmmakers avoid turning this into a sudden “light switch” moment, and that’s what makes his struggle all the more compelling and believable. It shows how deeply entrenched boys can be in a system of toxic masculinity—something you can’t simply escape.

Having been raised in an environment rife with machismo, Billy struggles to fully embrace ballet at first. He questions himself, even asking his best friend Michael, “Am I a puff [an offensive slang term for a gay man] just because I like to dance?” When his curiosity pushes him to learn more, he sneaks a ballet book out of the local library, rather than reading it openly. He hides his ballet shoes under his mattress, trying to prevent his father from finding out about his dance lessons.

For an 11-year-old, Billy is remarkably nuanced and conflicted. Much of that complexity comes through in Stephen Daldry’s direction and Lee Hall’s screenplay: they not only give him meaty scenes of raw emotion, but also frame his inner life through music that mirrors his feelings. Of course, none of this would resonate without Jamie Bell, whose performance is extraordinary. At just 14, he delivered a turn so layered and affecting that, in my view, it surpassed all the male acting performances of that year. If it were up to me, I would have handed him the Oscar over eventual winner Russell Crowe (Gladiator). Frustratingly, he wasn’t even nominated, but he did receive the BAFTA for Best Actor in a surprise, historic victory.

One striking example of his talent is the sequence where Billy vents his anger through dance after a confrontation with Mrs. Wilkinson and his family, set to The Jam’s “Town Called Malice,” a song written during Thatcher-era England about the disillusionment of the working class. In this scene, we don’t just see Bell’s physical prowess as a dancer—we experience his emotions through movement. His frustration and sadness over his circumstances unfold in a performance of remarkable depth and control. It’s a mesmerizing, unforgettable scene that makes clear why he was chosen from more than 2,000 boys for the role.

Music throughout the film often serves as an extension of Billy’s emotions, perfectly capturing his inner world. Another standout moment is the “I Love to Boogie” scene, which goes beyond being a spirited bonding moment between teacher and student: it shows how Billy and Mrs. Wilkinson, who often clash, ultimately find balance and connection through dance.

READ ALSO: Jaws At 50: The Story Behind Steven Spielberg’s Landmark Masterpiece

A Dance Of Defiance

While Billy grapples with societal pressure and his own self-expression, the film also explores other dimensions of gender and sexuality through his friendship with Michael. Raised in the same community and shaped by the same working-class values as Billy, Michael’s hidden sexuality is hinted at early in the film, such as the scene where he secretly dresses in women’s clothes while his mother and sister are away. The film also suggests his subtle crush on Billy, as he playfully compliments him for looking “wicked” in a tutu. Michael eventually comes out to Billy on Christmas Day, and to his surprise, his friend accepts him wholeheartedly. They even dance together for the fun of it afterwards.

This acceptance—especially between two young boys in a male-dominated community where homosexuality is stigmatized—makes a bold statement. It resonates not only within its 1984 setting but also in its 2000 release, a period when homophobia remained widespread, particularly in working-class environments. Billy Elliot was extremely progressive for its era, offering a humane and multidimensional portrayal of a gay character at a time when such roles were often reduced to caricature or ridicule in mainstream media.

Billy’s relationship with his family shows how understanding and support can still grow within a rigid, masculine household. On the same Christmas Day, Billy’s father, Jackie, walks in on the two boys dancing. In this part, one expects confrontation, a father chastising his son through words or physical aggression. But dance, once again, becomes Billy’s primary language: a hammer that cracks the seal of emotional repression between a man and boy, a father and son. Billy performs what has since been called “The Dance of Defiance,” showcasing his talent to his father. At first, Jackie appears disappointed and angry, as though the display confirmed his assumptions on Billy’s sexuality. But the man, instead of lashing out, walks away in tears, recognizing he’s been absent from his son’s life for too long because of the strikes, and deciding to give Billy a chance at his own future.

Swallowing his pride, he briefly returns to the mines to earn some money, hoping to help Billy attend the Royal Ballet School in London. When his older son, Tony, sees him going back to work, he rushes to stop him, insisting he shouldn’t give in to the government. Jackie then breaks down in tears, finally revealing the vulnerability of a man who has long maintained a hardened exterior in a world where “real men” aren’t supposed to cry. Witnessing this, Tony softens as well. He’d been judgmental about Billy’s ballet up until that point, but this is the first crack in his seemingly impenetrable wall, one that shows how every man in the community both reinforces and becomes victim to their own hardened culture. Though in the same vein, they’re just as capable of escaping and breaking the cycle.

Together, Jackie and Tony begin raising money: collecting coins and loose change, and even selling the jewelry that belonged to the family’s late wife and mother, to ensure Billy can attend the prestigious Royal Ballet School audition and pursue his dream. It’s impossible to discuss the film without touching on the relationship between art and social class. For a boy like Billy, dance is remedy, an escape from tough times, as he mentions in the simple but touching lines: “It sort of feels good. […] Once I get going, I forget everything. I sorta disappear. Like I feel a change in me whole body. […] I’m just there, flying…like a bird. Like electricity.”

The class barrier between Billy and ballet is clearly laid out. His audition peers at the Royal Ballet School are leagues farther than him in training, with the time and resources to pursue it. When you’re trying to survive, art takes a backseat; but what Billy Elliot shows us is, two contradictory truths can co-exist. Art, in this case, is its own kind of survival. It’s not the air we breathe, but it’s the reason why we want to continue breathing, despite everything. That in itself shatters class constraints, reminding us how art is for everyone, even when societal norms say otherwise.

The Transformative Power Of Art

The film ends on a deeply uplifting note, with Billy earning a place at the Royal Ballet School thanks to his raw talent. The final ten minutes are utterly beautiful, highlighting why Billy Elliot is not just inspiring entertainment, but also an exceptionally progressive film. Billy says goodbye to Mrs. Wilkinson, who, despite being a pivotal figure in his life, accepts that she will likely remain in the small town. He then shares a tender moment with the three men who have shaped his world: his father, with whom he finally reconnects; his brother Tony, who says “I’ll miss you,” revealing unfiltered vulnerability that hits hard after two hours of angry masculinity; and Michael, who Billy kisses goodbye—a quietly revolutionary gesture for a mainstream film at the time.

The story then jumps forward a decade, showing Billy as an adult and the lead dancer in a modern production of Swan Lake. Watching from the audience are the three men: Michael, now openly gay and in female clothing; Tony, an adult who has weathered the turbulence of youth; and Jackie, sitting quietly, almost in tears. The overwhelming pride and joy he feels at seeing his son break free from the potential path of the mines and flourish on stage radiates from the screen, striking an emotional chord that never fails to move me. I cry every time.

As Billy leaps off the stage, the swelling music carrying his triumph, the scene fades back to him as a child—jumping on his bed before any of the story unfolded, recalling the film’s opening moments. This full-circle ending reminds us that Billy Elliot is more than a story of talent; it’s a testament to the courage it takes to defy expectations, to move freely in one’s own skin, and to find grace in rebellion. It stands as one of the most important films of the 21st century, a landmark piece of cinema that conveys its progressive values without ever feeling preachy. It’s a remarkable work that subtly yet profoundly influences through the transformative power of film itself.