Guillermo del Toro’s lush, grand, and earnestly vulnerable adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein pays homage to its source material while deviating from it in surprising, meaningful ways.

Content Warning: This piece discusses key themes and plot points of both Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its 2025 adaptation.

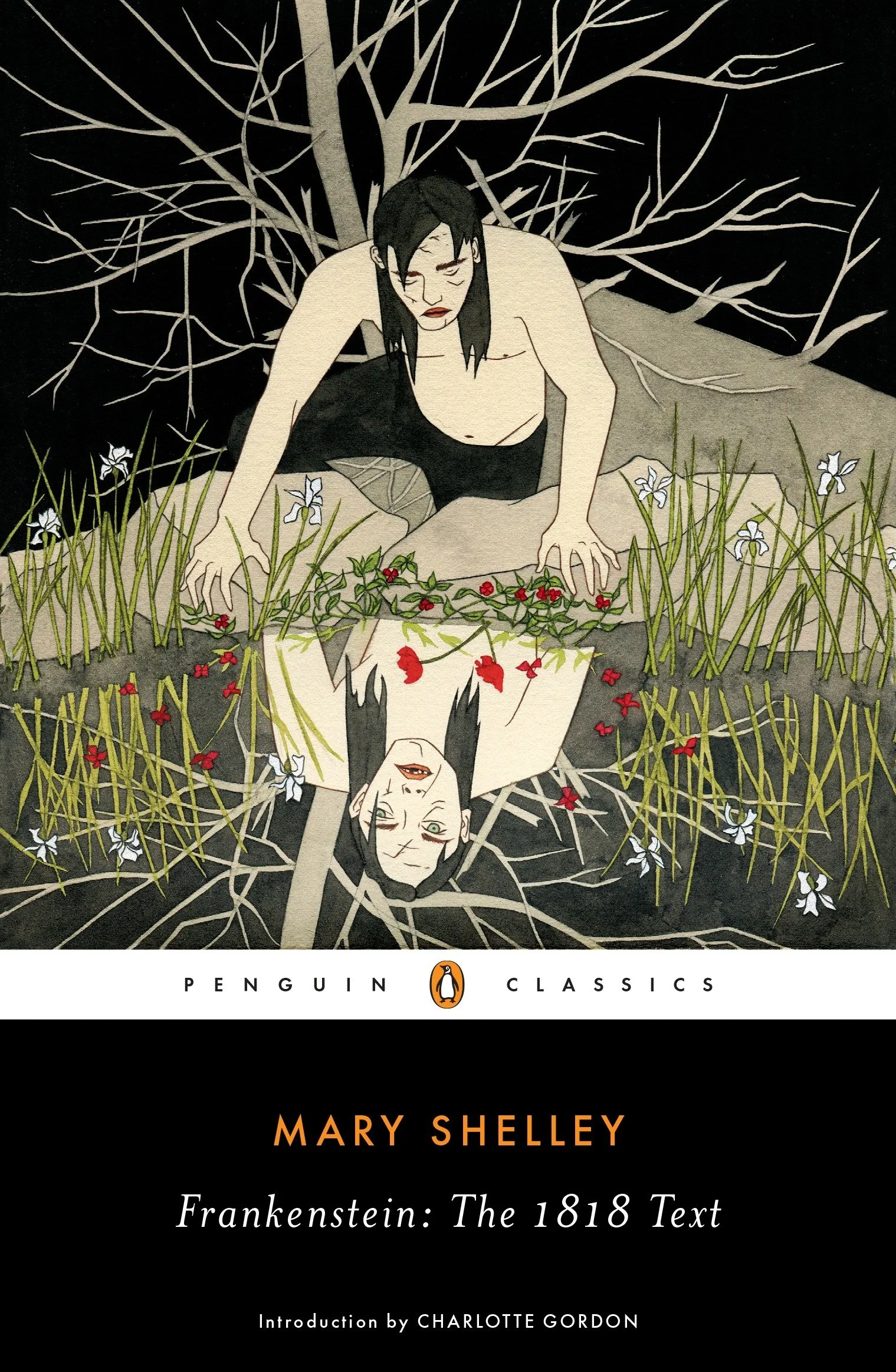

We’re fortunate to live in a timeline where, of all the filmmakers who decided to try their hand at adapting the beloved horror and sci-fi masterpiece that is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, it was Guillermo del Toro. With his abiding empathy for the monstrous and misunderstood, as well as his affinity for all things gothic, one could say he was born to helm the project—and indeed, having been a fan of Shelley’s since childhood, it’s been a passionate pursuit 30 years in the making.

I had high hopes that the film would capture the true spirit of its source material, and aside from a few small (emphasis on small, I’d even say they’re negligible, if I wasn’t putting my writer glasses on) bumps in narrative choices, I’m happy to report that it didn’t disappoint.

READ ALSO: Film Review: “Good Boy” Finds Horror In Helpless Devotion

A Human Touch

We need to mention the breathtaking technical feats of the film before anything else. Del Toro has stated in multiple interviews that he aimed to bring the handcrafted grandeur of Old Hollywood to the screen, and it’s a mission he accomplished with flying colors. Shelley’s novel begins in the barren Arctic, onboard a ship that rescues a sickly Victor Frankenstein (a role Oscar Isaac makes entirely his own), who later regales its captain Robert Walton, with his cautionary tale of creation and death.

The filmmaker stays true to that detail (though the British Walton and his fleet are replaced by a Danish-speaking captain and his crew), giving viewers a visual feast from the very first frame with a full-scale ship the production crew built from the inside out, which sails across a sprawling, icy landscape.

The director also minimized the use of CGI (save for maybe one or two scenes), sticking to his preferred practical effects and real stunts that give the film its grotesque, rough gravitas. Every frame was a morbidly stunning treat for the eyes, laden with the kind of human-made details the auteur prioritizes in his works; a very welcome act of vehemence against all things AI in today’s creative industry.

I wanted to get lost in the world of Frankenstein, much like I did when watching Crimson Peak, and found myself, during certain scenes, just admiring the sheer scope and density of the props, costumes, and sets. Bodies, chopped up and reconstituted, were disgustingly tangible—one scene with a gasping corpse being an absolute marvel to behold.

Costumes by Kate Hawley—who also designed the exquisite garments of Crimson Peak—add depth to the already richly-rendered film, once again proving that you can break the rules as long as you have a deep understanding of period piece fundamentals. Clothes aren’t strictly “accurate,” Hawley and del Toro wanting to add a modern flourish to the designs, as they reveal in the behind-the-scenes documentary Frankenstein: The Anatomy Lesson.

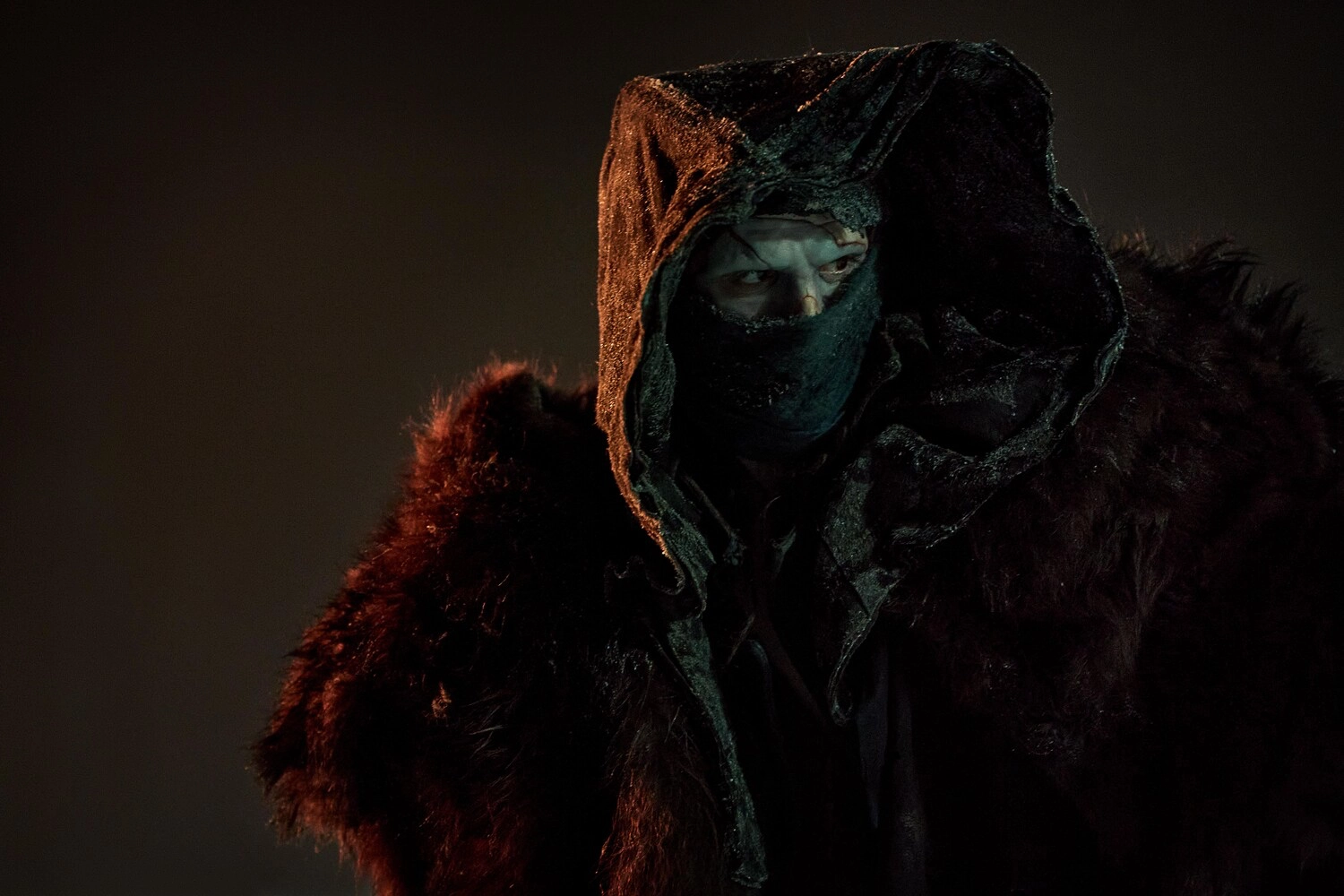

Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein has a rebellious, almost rockstar-like magnetism to him that’s reflected in loose, rugged outfits (and red gloves) that, admittedly, frame his body like fan service (not that we’re complaining, it just works). Of course, the one who gets the most gorgeous fits is Elizabeth Harlander (played by Mia Goth), Frankenstein’s soon-to-be sister-in-law and love interest. Wisps of structured yet flowy fabrics abound, her love of entomology reflected in shimmering, insect-like patterns. Even a tattered military coat worn by The Creature (an exceptional Jacob Elordi) bears skeletal patterns to showcase how it was scavenged from the remains of long-dead soldiers. It’s no exaggeration to say that Frankenstein is truly a film best experienced in theaters, where its full beauty can shine (which, for now, is sadly not possible in the Philippines, though we can hope for future screenings).

Where The Story Diverges

Del Toro expands on Shelley’s story and characters through a few notable changes, creating a narrative that infuses the text’s original themes with his own views on mortality, monstrosity, human nature, and the imperfections of love.

The movie takes from the book’s structure, unfolding in three layers much like Shelley’s three volumes. However, while the writer shifts between multiple narrators across all sections, del Toro organizes the chapters into a more clear-cut “he-said-she-said” framework: the film begins and ends in the present—The Creature chasing Frankenstein across the Arctic—while the middle section is split into two parts, the first from the scientist’s perspective, and the second being The Creature’s own story.

A few new (or reimagined) characters flesh out the film’s emotional core. Frankenstein’s siblings play a minimal role in the text, yet in del Toro’s version, his younger brother William (Felix Kammerer) becomes his only sibling and foil. Kammerer’s character is noble and gentle, willing to go to great lengths for his brother while quietly fearing his darkness.

Frankenstein’s paramour and eventual wife in the book, Elizabeth Lavenza (who happens to be his first cousin), is reborn here as “Elizabeth Harlander,” now the fiancée of William. And while blood-related incest is now out of the equation (not that the filmmaker has ever shied away from it), Frankenstein still pursues his brother’s bride-to-be.

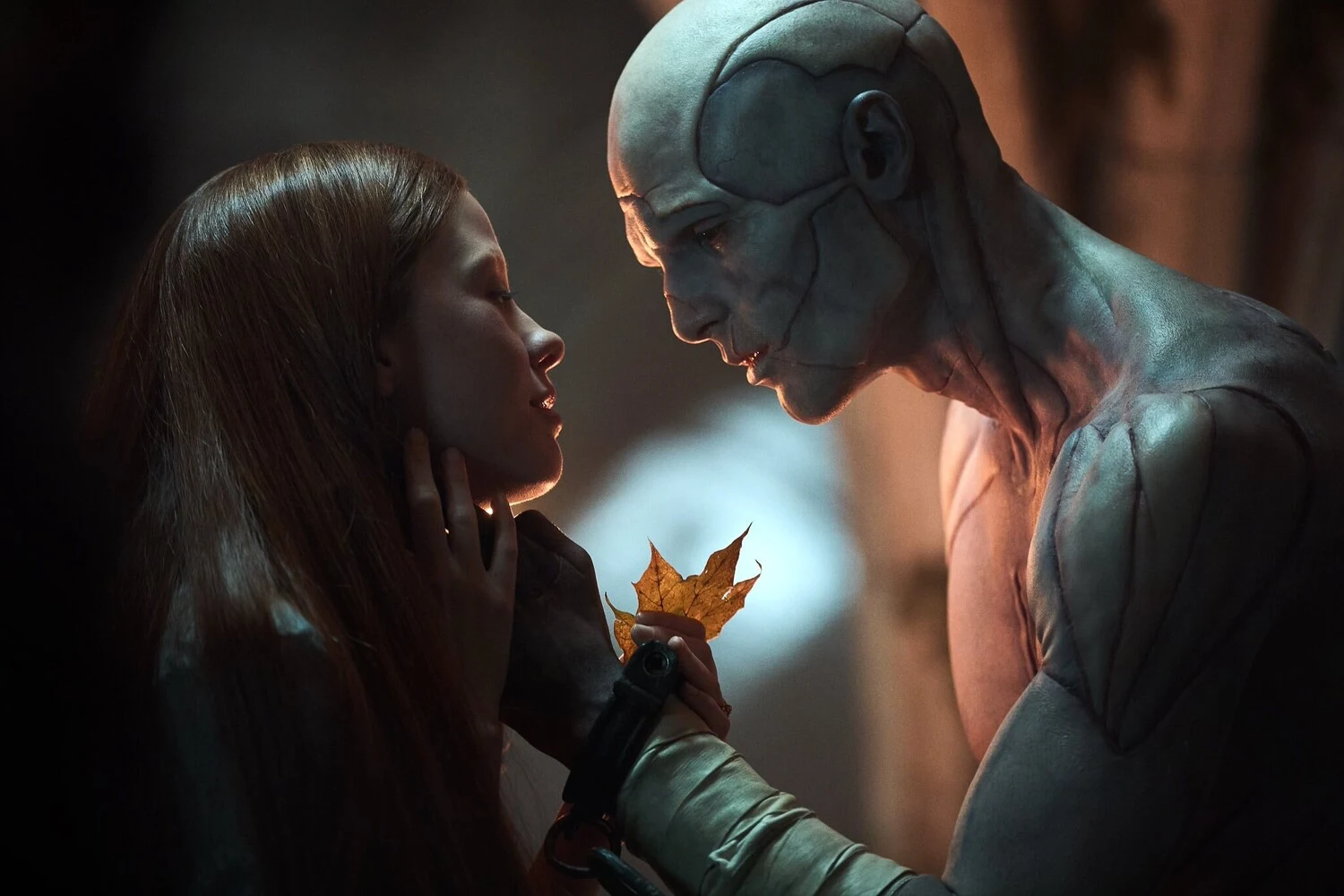

Perhaps the most interesting development is, in typical del Toro fashion, the tender bond that forms between Elizabeth and Elordi’s Creature, somewhere between maternal and romantic. Elizabeth, like her literary namesake, is pious, delicate, and gentle, the ideal female figure of her time, though Goth and del Toro also infuse a kind of repressed, electric eccentricity to the character that gives her empathy more weight. Her presence not only heightens Frankenstein’s disdain towards his creation (partly fueled by jealousy), but also highlights the paradox of his humanity (he momentarily forgets his ambitions as he falls in love with her) and utter lack of kindness; she’s both temptation and moral compass.

A new addition, completely of del Toro’s invention, is Elizabeth’s salacious and wealthy uncle Henrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz), who funds Frankenstein’s experiments for his own self-serving reasons. Admittedly, his subplot is the film’s weakest link; it mainly explains how Frankenstein can afford the materials for his experiments (his family fortune having dwindled in this version). Still, Waltz’s performance is charismatic enough to make you forget that quibble in the moment.

The Outcast Son And Prodigal Father

James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein (starring Boris Karloff) and the Hammer film series have their merits and cultural influence, but fans of the original text can’t deny that much of Shelley’s vision and thematic nuance got lost in translation. Del Toro’s version is arguably the one that understands—again, not faithfully, but with great care—the writer’s work the most. And it does this by showing us “The Creature” as she conceived him: a complex fusion of the hideous and the beautiful, intelligent yet sensitive, born with naivete before hardening into lonely, existential anguish.

The Creature in the 2025 film stands in striking contrast to the grunting, green, bolt-studded caricature we’ve come to know, a figure that has swung between stoic monstrosity and camp over the years. Elordi knocks the role out of the park, introducing the creation as an impressionable, childlike being who seeks companionship and eventually comes to detest his “wretched” existence, much like his literary counterpart. The film almost plays like a coming-of-age story: a child maturing into a lost adolescent, consumed by confusion, rage, and that sense of not belonging.

Del Toro adds a new dimension to the tale: regeneration. Shelley’s creation is immortal in the sense that he’s impervious to age and disease, but not necessarily death. In the film, however, this Creature heals from even the most grievous wounds, trapped in eternal limbo and growing angrier as he realizes he can’t even be granted the sweet release of death. “There was silence again, and then…merciless life,” he laments.

Shelley’s text has always been a creation myth of sorts—drawing inspiration from Paradise Lost and the Book of Genesis—a story of Creator and Creation, as well as a warning about the consequences of unchecked ambition. But deeper still, it’s a story of parent and child. Shelley made this explicit, referring to the Creature as “progeny” and “offspring” in her 1831 introduction. Frankenstein is, at its heart, a portrait of a parent who deserts their child, refusing to claim them despite having brought them into the world—and of that child, who never asked to be born, desperately seeking love or approval. Shelley never knew her mother, the pioneering feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, who died just 11 days after her birth. This early loss—and the many encounters with death that followed, including the untimely passing of her children and her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley—likely shaped her profound understanding of abandonment and isolation, themes that resonate throughout her work.

Del Toro’s film elevates this heartbreak through stunning performances from both Isaac and Elordi, framing the dynamic as a struggle between nature and nurture: both book and film Creatures are inherently gentle, yet shaped into violence by the cruelty the world shows them for simply being themselves. The director returns to the story’s emotional core through a fractured father-son relationship, a deeply personal preoccupation he also explored in his stop-motion Pinocchio, which could be seen as this film’s spiritual twin.

The Frankenstein of Shelley’s novel grows detached upon the success of his experiment, regretful and fearful, but Isaac’s scientist initially reacts like a new father: ecstatic, beaming with pride, eager to teach his creation about the world. The Creature knows only his creator’s name, parroting it like a toddler. Yet after achieving the impossible, Frankenstein faces a kind of post-partum despair—“I never considered what would come after creation,” he admits. That despair curdles into resentment as he grows frustrated with The Creature’s perceived lack of intellect, echoing his own late father’s disappointment in him. Here, del Toro transforms the tale into a study of generational trauma (and let’s be honest, there’s nothing quite as horrifying as parental neglect).

Shelley’s Frankenstein enjoyed a happy, privileged upbringing under loving parents who encouraged his intellect; del Toro’s Frankenstein, by contrast, is forged in loss and abuse, with a doting mother taken too soon (she passes away in the book, but during Frankenstein’s teenage years, and by catching scarlet fever, rather than dying through childbirth), and a father who could never see him as the ideal son. These wounds mirror his own cruelty toward his creation, completing del Toro’s tragic cycle.

Beyond The Freezing Horizon

Yet another surprising twist lies in the film’s ending. In both the film and Shelley’s book, The Creature confronts Frankenstein for the last time aboard the Arctic vessel. But the novel’s conclusion is far more open-ended, offering little in the way of closure, which is precisely what makes it such fertile ground for interpretation. The Creature arrives to find his Creator already dead, and, realizing he is now truly alone and without purpose (his quest of inflicting revenge on his creator now over), vows to travel to the farthest reaches of the earth and end his existence through immolation. Whether he actually does so, Shelley never specifies, leaving it up to the reader’s imagination.

The movie, on the other hand, delivers resolution. The Creature watches Frankenstein die, but just before life leaves him, the scientist apologizes for his cruelties and rejection, urging his Creation to forgive himself “into existence” and embrace the reality of his deathless life by becoming who he wishes to be. “While you are alive, what recourse do you have but to live?” he asks. In his final moments, Frankenstein even calls him his “son”—a cathartic acknowledgment that closes the film on a surprisingly hopeful note. (Though it does remove that aspect of accountability Shelley brought to the novel by refusing to grant Frankenstein closure and “forgiveness” for his mistakes.)

And after all the suffering and cruelty The Creature endured at the hands of humans, what does he choose to do? He helps the Danish ship trapped in the ice, pushing it free so its captain and crew can sail away. “Choice is the seat of the soul,” Elizabeth tells Frankenstein in the film. “The one gift God granted us.”

The 2025 film was never meant to be a 100% accurate adaptation, but it’s a highly enjoyable one that brims with heart, focusing less on page-by-page faithfulness and more on thoughtful dialogue between a filmmaker’s love for a source material and its timeless themes. Like its nuanced, otherworldly being, del Toro’s work is a chimerical creature that’s an aching reflection of all the best and worst parts of us.

“Frankenstein” (2025) is now streaming on Netflix Philippines.

Photos courtesy of Kinorium (unless specified).