In 1818, Mary Shelley imagined an artificial being who sought humanity through books, while we now use AI to avoid reading them. On International Literacy Day, Frankenstein’s creature offers a powerful lesson about the difference between accessing information and developing wisdom.

UNESCO’s International Literacy Day arrives under the theme “Promoting literacy in the digital age,” which feels particularly urgent here in the Philippines. The 2024 Functional Literacy Survey revealed that 18.9 million Filipinos aged 10 to 64 are classified as functionally illiterate. They lack the reading comprehension skills needed for daily life and work. While it involves complex socioeconomic factors, UNESCO’s theme highlights the digital age dimension and the questions it raises about how technology shapes our relationship with reading and critical thinking.

And when we talk about mass technology today, it inevitably becomes a conversation about artificial intelligence (AI) and the ubiquitous use of AI chatbots in the past few years. Recent data shows that over half of Filipino students now rely on AI to summarize academic articles, generate texts, and complete other tasks, bypassing the cognitive work that reading requires.

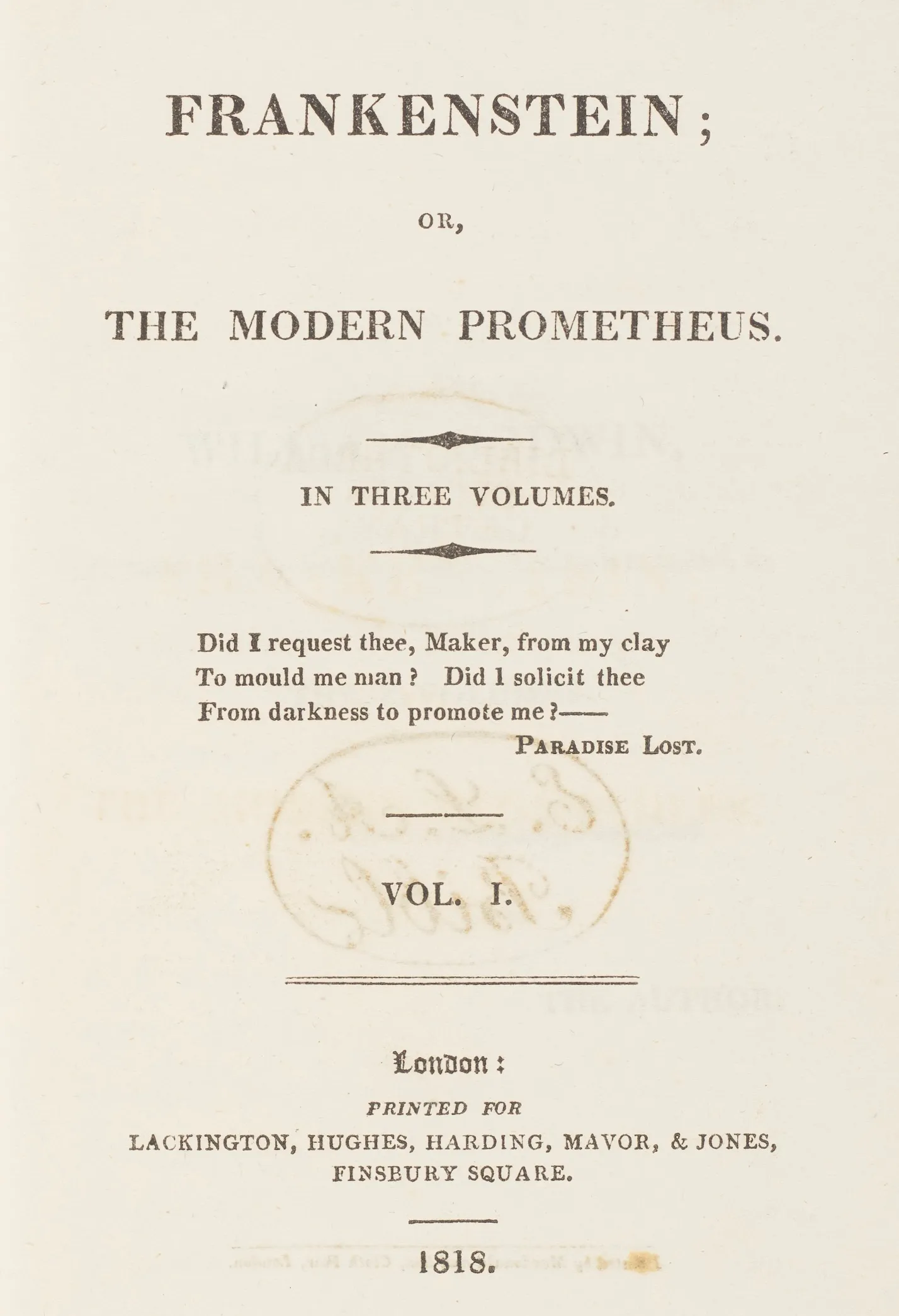

These concerns brought me back to a novel I first encountered in middle school: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (perhaps I have a penchant for the Gothic). Widely recognized as the first true work of science fiction, a genre born precisely to explore the implications of technological advancement, it offers an apt lens through which to examine technology’s effect on literacy and human understanding.

What makes this connection particularly striking is that Frankenstein also gave us one of the earliest visions of artificial intelligence. But while Shelley’s creature desperately sought to understand humanity through reading, today, we increasingly use AI to avoid the very act of reading that created understanding in her tale.

READ ALSO: Books By Female Authors To Read This Women’s Month

The Birth of Science Fiction And AI Prophecy

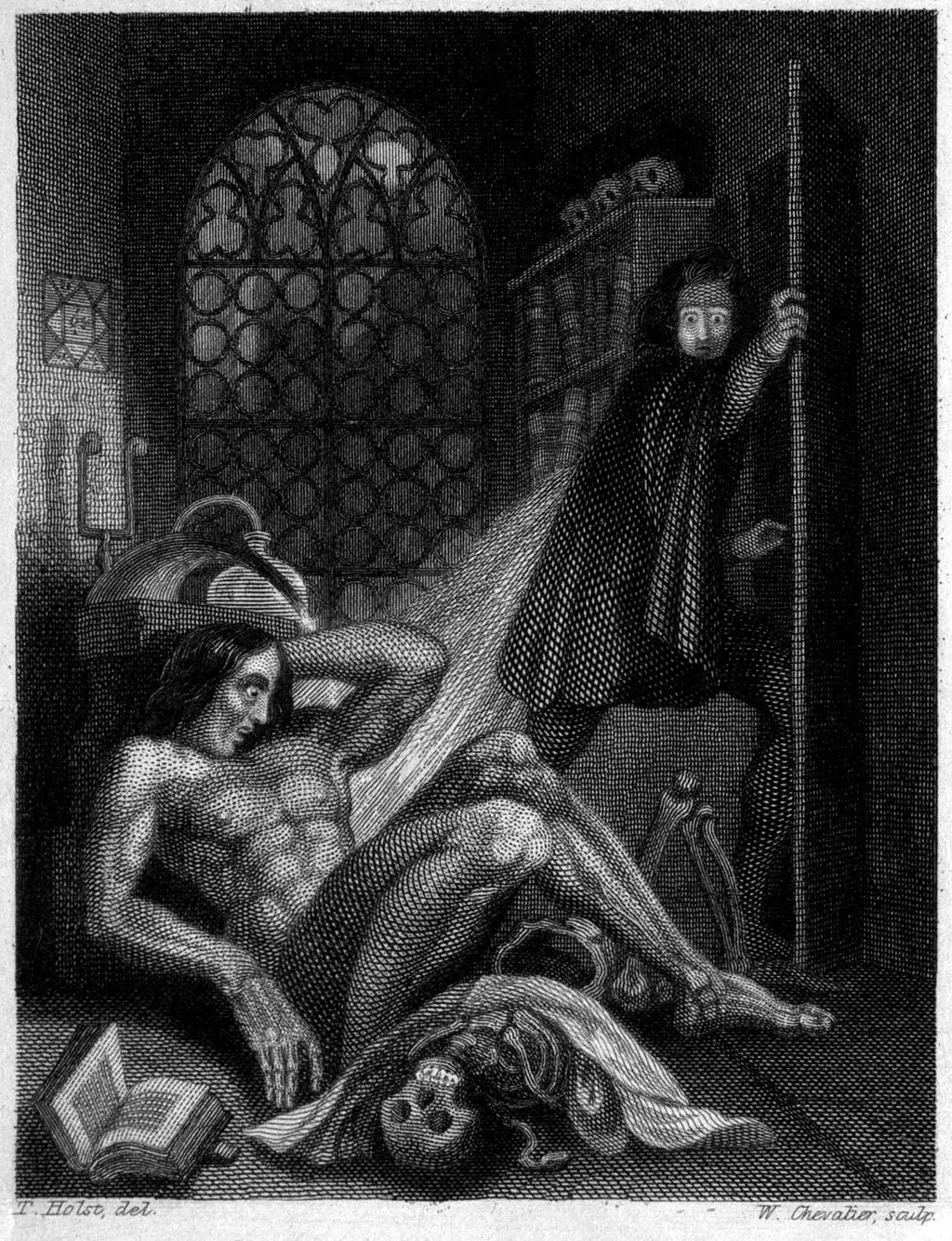

Frankenstein emerged from that famous ghost story contest at Villa Diodati in 1816, when Shelley conceived what would become literature’s most enduring technological nightmare. The novel opens on the ice caps with Arctic explorer Robert Walton rescuing scientist Victor Frankenstein, both men united in their obsessive pursuits, isolated at the ends of the earth. Victor recounts to Walton how his quest to understand the secrets of life led him to create artificial life, only to abandon his creation immediately upon animation. The nameless creature, left to navigate the world alone and repeatedly spurned by society, ultimately turns to revenge.

Shelley is widely regarded as the “mother of science fiction,” and Frankenstein represents what writer Brian Aldiss called a “triumph of imagination: more than a story, a new myth.” The novel’s subtitle, “The Modern Prometheus,” signals its central concern with the theft of divine knowledge and the consequence of overreaching human ambition. Yet as Joyce Carol Oates observed, the very name Frankenstein has supplanted Prometheus in popular usage when we discuss the dangers of pursuing forbidden knowledge. The shift speaks to the novel’s enduring relevance in our technological age, where electricity, computing, and now AI have created a distinctly post-Frankenstein world of human-made intelligence.

That is because the creature is also literature’s first conception of AI. Academic Eileen Hunt Botting observed that the creature exhibits the key capabilities we now associate with deep learning, or advanced AI: learning to recognize faces and speech patterns, translating languages, reading handwriting, developing strategic thinking, and controlling robotic prostheses. Shelley imagined AI emerging “from the flawed yet powerful image of humanity,” a prescient insight about how our creations reflect our limitations and biases.

The Creature’s Deep Learning Education

The creature’s education unfolds with what Botting describes as “the efficiency of a computer and the intensity of a child.” After his abandonment by his creator, the creature spends a year secretly observing a local family through a hole in their cottage wall, learning language, social customs, and human emotion through patient observation. His self-education through stolen books, from Milton’s Paradise Lost to Plutarch’s Lives to Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, informs him, while also shaping his understanding of morality, history, and his own tragic position as an outsider.

In his engagement with Paradise Lost, for example, he goes beyond extracting plot points to find profound personal meaning. He sees himself as both Adam and the fallen angel. This sophisticated interpretation helps him process his own experience of abandonment and marginalization while developing a framework for understanding power, justice, and his own position in the world.

“As I read, however, I applied much personally to my own feelings and condition,” the creature reflects at one point in the novel. “I found myself similar yet at the same time strangely unlike to the beings concerning whom I read and to whose conversation I was a listener. I sympathised with and partly understood them, but I was uninformed in mind; I was dependent on none and related to none.”

Crucial, also, is that the creature reveals this journey on his own terms. In the novel, the creature demands that Victor (and through him, us, the reader) listen to his complete account. The nested narrative structure reinforces how knowledge transmits and could be misconstrued if abbreviated. The creature’s own story requires the full context of his struggle with language, literature, and social understanding.

Intelligence As Cognitive Prosthetics

The creature’s educational process reveals something fundamental about how intelligence develops, not just for artificial beings, but for humans as well.

François Chollet, a leading AI engineer and researcher, explored this concept in his influential 2017 essay “The Implausibility of Intelligence Explosion,” which argued against then-predictions that AI would rapidly surpass human intelligence. Instead, Chollet emphasized how human cognition and intelligence actually work.

“The most fundamental of cognitive prosthetics is of course language itself,” Chollet writes, “essentially an operating system for cognition, without which we couldn’t think very far.” His key insight: our cognitive abilities don’t reside in our brains alone but in external systems developed over thousands of years. “Most of our intelligence is not in our brains,” he argues, “it is externalized in our civilization.”

Language, literacy, and reading represent precisely this kind of external cognitive process. It is a way of running threads of thought across time, space, and individual minds. The creature grasped this when he taught himself to read through stolen books, acquiring access to externalized intelligence of civilization.

Chollet positions AI optimistically as “no different than computers, or books, or language itself: it’s technology that empowers our civilization.” Yet what he doesn’t fully anticipate in 2017 is how AI might erode the very literacy that built our cognitive foundations. Intelligence, as Chollet notes, is adaptive to a situation.

The situation today? Information can be instantly summarized, complex arguments can be reduced to bullet points, and the struggle of interpretation can be eliminated entirely.

READ ALSO: AI Vs. Humans: Who Wins?

On Abandonment

Frankenstein anticipates our current crisis through Victor’s relationship with his creation. He abandons the creature immediately after animation, refusing to take responsibility for his education and integration into society. The creature, despite his literacy and eloquent self-expression, is continuously rejected by society.

When the creature finally confronts Victor, his literacy gives him voice and agency. When Victor refuses to provide the creature with a companion, the creature’s subsequent violence isn’t random but calculated and symbolic, informed by his own understanding of justice and revenge. Yet at the novel’s end, it’s the creature who shows growth and remorse, while Victor continues to be consumed by destructive obsession. The irony is complete: the artificial being is more human through reflection, while the human becomes machine-like in his thoughtless pursuits, first toward knowledge, then toward revenge.

We go back to Chollet’s insights about intelligence being externalized in and as civilization. The creature understood that becoming human required accessing collective human knowledge, yet society denied him the social connection that would complete his integration.

We now face a similar moment. But where the creature sought connection through patient reading, we’re collectively turning away from the cognitive work that builds understanding. Society rejected the creature despite his hard-won literacy; we’re rejecting literacy itself in favor of AI convenience.

Early research is already revealing the consequences of this choice. Studies suggest that AI chatbot usage could harm learning, particularly for younger users, with researchers noting that “as society increasingly relies upon [AI tools] for immediate convenience, long-term brain development may be sacrificed in the process.”

The mismatch between our technological power and our wisdom in wielding it echoes throughout our digital age. We possess unprecedented access to information, yet show declining reading comprehension and critical thinking skills. We’ve created artificial intelligence to handle the very processes that create intelligence in the first place.

Prayers Of The Faithful

On this International Literacy Day, with its focus on the digital era, I repeat, the stakes feel particularly urgent here in the Philippines. While the aforementioned 19.8 million Filipinos remain functionally illiterate, a complex challenge requiring a systematic solution, there’s another troubling trend that is perhaps within my reach to address: the decline in leisure reading.

Reading for pleasure is a practice that directly strengthens comprehension and critical thinking skills. This brings me back to Frankenstein, which shows us how engaging with complex texts develops not just reading ability, but the capacity for moral reasoning and independent thought. The novel endures as a cautionary tale not because it opposes technological progress but because it insists on the moral dimension of creation.

This reading of Frankenstein through our AI age is, of course, just one interpretation. And this is precisely the point. The novel rewards personal engagement and fresh perspectives. I encourage everyone to read it and form their own interpretation, developing the very literacy skills that AI shortcuts threaten to erode.

The choice before us isn’t between human and AI, but between tools that build literacy and intelligence, and those that diminish it. When we choose to read, to struggle with complexity, to sit with ambiguity, and to form our own interpretations, we distinguish human intelligence from artificial processing and thus contribute to the civilization-wide intelligence that makes all human progress possible.

Banner photo includes still from “Frankenstein” (1931) courtesy of IMDb, and Puffin Clothbound Classic edition of “Frankenstein” courtesy of Penguin official website