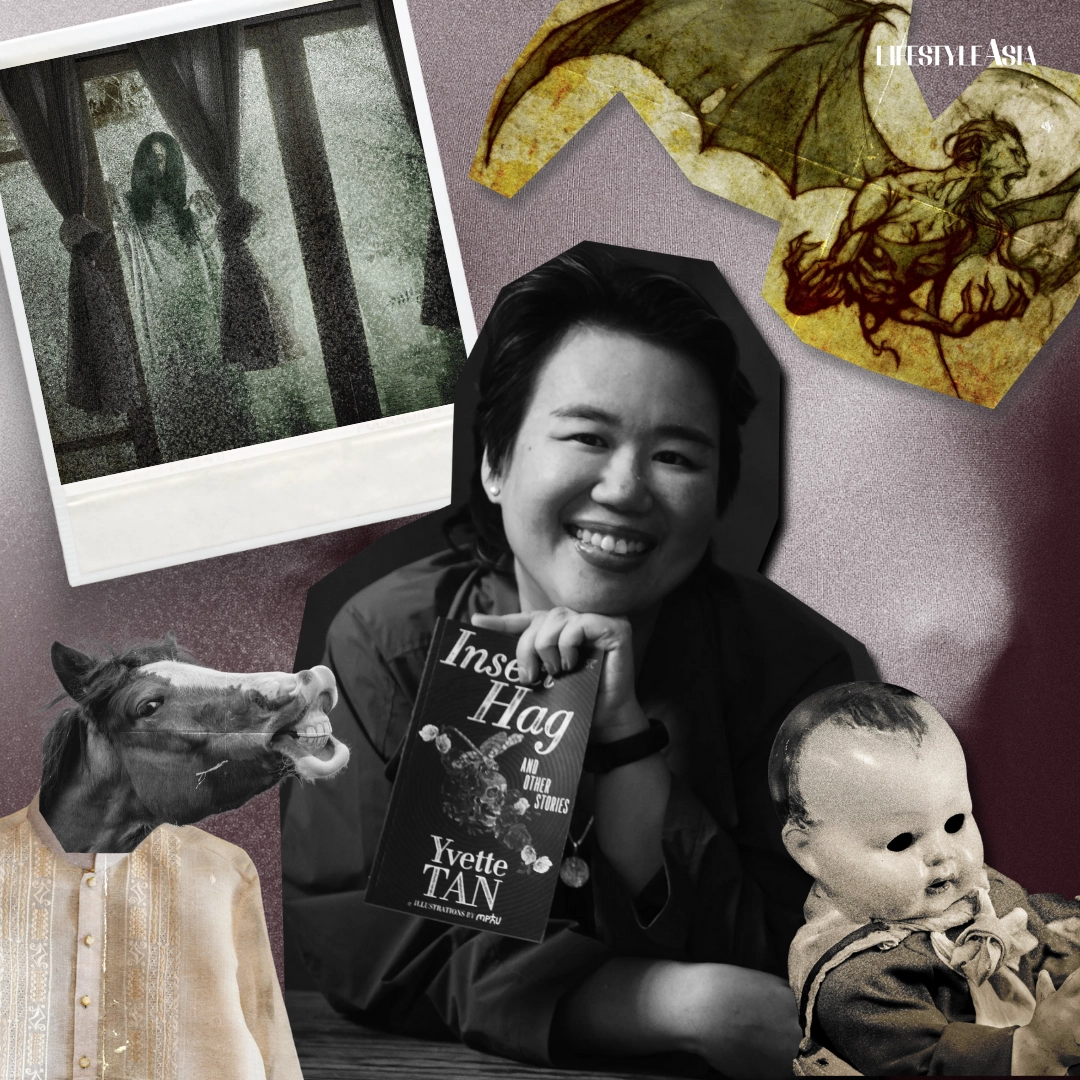

With stories that tap into the Filipino psyche and experiences that hit close to home, Yvette Tan explores the quiet, familiar terrors that haunt us, and why true horror goes beyond blood, gore, and jump scares.

“For too long, horror has been treated as a homogeneous entity, a single brushstroke applied to all of it. Horror is never, and was never, just one thing,” writes Anna Bogutskaya in her book Feeding the Monster: Why Horror Has a Hold on Us. Then we must ask: is horror really a genre, or something far less containable? The answer leans toward the latter; it’s both personal and collective, ancient and immediate, quiet and grotesque. And because it holds so many forms, horror has long been a vessel for writers, filmmakers, and artists who recognize that its power runs far deeper than the viscerality of a scare. In honor of the Halloween season, Lifestyle Asia had the pleasure of speaking with Yvette Tan, a writer best known for her stories that tap into Filipino fears, superstitions, and haunting realities.

READ ALSO: Why Is Horror Seldom Recognized By The Academy Awards?

An Interview With Yvette Tan

While Yvette is described as “one of the Philippines’ most celebrated horror writers,” her practice transcends the convenience of labels. Her stories “Kulog” and “Sidhi”—both featured in her first, critically-acclaimed short fiction collection Waking the Dead and Other Stories—won Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature in different categories in 2003. Since then, she has released lauded short story collections under Anvil Publishing, expanding her creative range to include screenwriting and ballet librettos, among other projects.

In our conversation, Yvette reflects on the enduring pull of horror, how Filipino culture shapes her storytelling, and why the most unsettling stories often spring from the familiar. What follows is an exploration of fear: not just as spectacle, but also as emotion, memory, and mirror.

If you could define horror in a sentence, how would you describe it?

Yvette: Horror is more than what scares you. What I tell people is, “Horror isn’t a genre, it’s an emotion,” to quote American horror editor Douglas E. Winter. And that’s just describing it in one to two sentences. What I mean by that is—especially in the space that I write in—people think of horror as monsters, takutan, and that’s it. But it really encompasses more than that. You don’t have to write about the supernatural to write something horrific, because war is horrific, murder is horrific. Unfortunately, in the media, it [horror] tends to be pigeonholed into one thing, when it should be so much more.

What initially drew you to horror, and do you think your relationship with it has changed over the years since that time? In what ways?

Yvette: First of all, the disclaimer I want to tell everyone—which a lot of people find funny—is that I’m super takutin. I’m a scaredy cat. I’ve always been interested in the supernatural, even though I’m very scared of everything. But growing up, I wasn’t really interested in horror as a genre, because like everyone else, I thought it was all monsters and jump scares.

But then my friend in college lent me a book that made me fall in love with horror [Wormwood by Poppy Z. Brite]—and it was really the way the words were put together. I fell in love with horror fiction because of the language. And when I started writing my own stories, I didn’t even know it was horror.

I started in college. It took another friend, who’s also a horror writer now, to tell me that the work I was putting out actually fell under horror. It’s the closest word to describe what I write, even though I don’t really think my stories are scary. We’re very used to labeling, so I just went with it.

But recently, somebody pointed me towards the term “tropical realism,” which I feel makes more sense in my writing. So what’s tropical realism? With the way I write, some people complain that it’s not scary, some people like that it’s not scary. But I write like how it is in the Philippines. Even if we live in Manila, we know somebody who knows somebody who has had a weird encounter with a supernatural thing. Like, people who have gone to school in the Philippines have always heard of their school being a cemetery, dating sementeryo, or a church. That’s why I feel like tropical realism fits my work more—but of course, for marketing purposes, everyone puts me in horror because it’s easier that way.

If you don’t mind us asking, what was the very first horror story you had ever written, and what inspired it?

Yvette: One of the very first horror stories that I wrote is included in [my collection] Insect Hag. It’s a story called “Wings.” It’s about a guy who returns to the province to see his ex-crush. I’m glad that people like it, because it was written in the late ‘90s, so it’s a very, very dark, goth, angsty, college thing. I thought that it would be this whole universe with the same characters, except that’s the only story of that character that’s been published.

Another one, which came a bit later because I wrote it in college, is “Delivering the Goods,” which is in Waking the Dead. It’s also one of my earliest publications; that was a retelling of an urban legend that was going around that time, where somebody accosted this guy holding a baby in the airport that was sleeping—and then, yun pala, the baby was dead and full of drugs.

Women have always been closely affiliated with the horror genre for different reasons. Filipino women play integral roles in a lot of your stories—what makes horror a compelling vehicle for exploring their experiences?

Yvette: The stories I tell are stories I want to tell. I took up Comparative Literature for my master’s, and that was exactly my thesis. [laughs] So I have an academic background on why that is. They usually talk about it in terms of horror cinema, but I’ve translated it into horror literature.

In horror cinema, it’s very easy for the woman to be “the other.” Thankfully, it’s changing now, but before, we looked at everything from the point of view of a straight, white man. So anything that wasn’t straight, white, or male was an “other.” It was easy to make everything that was feminine “the other.” Which is why you have a lot of themes in horror cinema that are very feminine, like the vagina dentata or “vagina with teeth” [in which women’s genitals are depicted as having teeth capable of castration; a symbolic portrayal of male fears surrounding women’s sexuality and power] or the “final girl” in slasher films—the girl who always survives has to be “pure,” she shouldn’t have sex or do drugs. It just calls back to the idea that you have to be “pure” to survive the horrors.

That’s the scholarly interpretation of it; but also, if you just want to get a bit more esoteric, women have always been more in tune with their intuitive side than men. That could be a factor as well. Not even in horror media, just regular, supernatural stories that you hear from your kapitbahay or neighbor. It’s always, yeah this house is haunted, and it’s the woman who will see it; the men always disregard her feelings or her experiences because she’s a woman, even when it’s really happening—but when it happens to them, that’s when they’re like, “Oh, she wasn’t lying.”

These cases don’t just happen within supernatural stories. I mean, for example: childbirth, abortion. I’m 100% sure that if men could give birth, abortion would be legal. Women are dismissed in every aspect of society, not just in horror. And I think that is the point, that is the horror of it all. In medicine, people only started using blood to test menstrual products super recently—I think within the 2020s. It’s super recent.

And you know how strong women were always turned into monsters over time? So the midwives became witches when Catholicism came in. Or women who could survive by themselves were always cast out, or society always found some way to take their lands from them because they had “no man to defend them.” Even the word “spinster”: now, it means a sad old maid. But before, it used to mean someone who “spun” [fabrics, garments]. These “spinsters” didn’t need men because they could make their own money—they were independent. But a patriarchal society turned this word that meant “independent woman” into someone who’s super “kawawa na walang asawa.”

So we have the scholarly part of it, and then we have what’s really happening in society. There are so many aspects to why women are associated with horror and it has to do with real life and how women are treated.

Do you think that what Filipinos consider “scary” is entirely subjective, or are there collective fears that haunt us as a nation? What are these, if so?

Yvette: Well, I think there are things that collectively scare us as a nation, which have to do with history, and also how we as a people don’t like facing history. We like sweeping everything under the rug—which I think is the scary part. I also think there are things that are universally scary, regardless of nationality: the threat of uncertainty is always scary. I guess it’s how you weave a story that will matter.

There will be things that are scary to some, or scary to all. But even if it’s a fear that’s scary to some, depending on the way you tell it as a storyteller, you can turn it into a fear that will be scary to all, because other people will be like, “I never thought of that, but now I’m scared!”

Do you think our notions of what’s frightening has vastly changed over the years? (Eg. superstitions grounded in folklore/myths vs. modern horror that reflects our increasing globalization, urbanization, climate crisis, etc.)

Yvette: Going back to the scholarly study of horror, especially horror cinema: there’s a school of thought where horror is a direct reaction to what’s going on in society at the time. It’s easiest seen in American cinema, like the examples I gave.

In the 1950s, American cinema was all about big creatures, radioactive creatures that become big and start attacking people. It was also the same in Japan, because we were all fresh from the war. Then before World War II, it used to be classic creatures: Dracula, Frankenstein, so on and so forth.

In the ‘60s to ’70s, because there was a sexual revolution in the [United] States, a lot of their movies centered around lesbian vampires, that sort of thing. In the 70s, there was a fear of the collective: this is where we get zombie movies or killer movies. Then in the ‘80s, because there was a shift to the conservative, we had all the slasher films where only the pure final girl gets saved.

In the Philippines, my theory is that, until now, our fears have remained the same. It’s always the White Lady, the mananangal. The biggest shift was in the ‘80s, when Peque Gallaga and Lore Reyes were super active and introducing monsters like the tiyanak through the Shake, Rattle, & Roll films [a Filipino horror anthology series].

It’s always been the same—and that’s because our concerns haven’t changed much. It’s 2025 and we’re still surviving as a country, trying to get by day to day. Our worries are floods, corruption. It hasn’t changed, and maybe that’s why our monsters haven’t changed. That’s why people try to import—import talaga—foreign monsters and try to bring them into the Philippine soil, but we’re still stuck in survival mode; so the monsters that still resonate with us are still the ones from our past.

But even though our concerns remain the same, they’re slapped on top of all the things that are happening globally. The floods are getting worse; there’s the climate crisis to contend with; we still have corrupt politicians stealing our infrastructure money.

And this doesn’t mean our folklore has stopped. For example, in the call center industry—it’s fairly new, right? Most of the call centers are in new buildings, but they have their own folklore revolving around supernatural things. It’s still very Filipino, very organic. Folklore is ongoing, it’s evolving—but it’s evolving in a very Filipino way that doesn’t deviate from our reality of just trying to survive.

What are your thoughts on “internet horror” or “digital horror” (horror centered on current technologies), and how it fits into our current milieu?

Yvette: I’m super interested in that—how the supernatural will use whatever is there to show itself. Even before the internet, there’s always been an intersection with the supernatural and technology. Phone calls from people who aren’t with us anymore—that’s super analog, right? One of my stories [“Daddy”] involves getting phone calls from my dead father through my cellphone. When the internet was new, it wasn’t even the internet, we had Ring (1998), which was super popular, and that was through television.

I don’t think there’s a distinction, really, between technology versus “spirit of the glass” type things—if you think about it, that’s a type of technology, it’s just not high-tech.

I’ve experienced it firsthand. I was in Romblon, and I overheard the caretaker of my friend’s beach house talking to her son. He said that he got a mass text saying that a group of aswang had escaped from police custody and were making their way to our island, and she was like, “Yeah, I got that text also. We’re going home early tonight!” And I thought that was fascinating. [laughs] Now you don’t have to wait for your kapitbahay to run to you and say, “May mga dumadating!” Now it’s just texting, “Uy, magtago kayo!”

What, to you, are the elements that make up a truly unforgettable horror story?

Yvette: I think it has to have heart. It can’t just be for the scares. The horror stories that I’m drawn to are the ones that are crushing. I like to tell people that behind most ghosts—not every, because some ghosts are created by happy circumstances—is a story of heartbreak. It’s always about an emotion, and two, it’s political.

Why is the spirit stuck on earth, what happened to them? Good or bad? Usually it’s bad. What were the circumstances that created this horrible thing for the spirit to be stuck on Earth? And it usually has to do with something political. Actually, it’s always something political. Is it patriarchy, is it a societal thing, is it current events that caused this?

So yeah, for a powerful story, a lot of the horror comes from the “living on earth,” human part, versus the gulatan part.

Off the top of your head, could you give three recent horror films, shows, books, or any form of media that you’d recommend to our readers this Halloween season, and why?

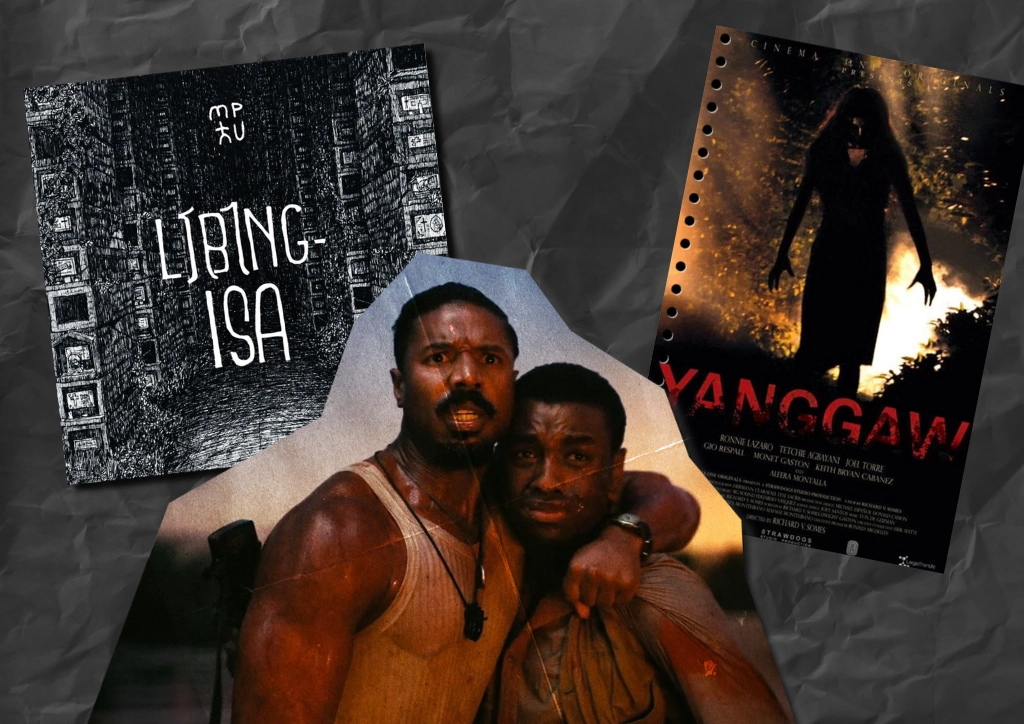

Yvette: I really like [the comic] Libing-Isa by Malayo Pa Ang Umaga, who, coincidentally, illustrated Insect Hag. And that wasn’t on purpose—I was a fan before my publisher recommended them.

And Sinners (2025)! I think it’s definitely my favorite movie of 2024, but also one of my top favorite movies ever, because there’s so much meaning to be drawn from it. On the surface, it’s a fun vampire film. But if you get into the history of why certain choices were made in terms of the writing, the era, the costumes, everything was planned in minute detail. Everything is a commentary on how black people and Asians—non-white people–were treated in that specific era. I think it’s a great example of how something can be entertaining, but also very scholarly, very deep, very entrenched in history and politics.

The third one isn’t new, but my favorite Filipino horror film has always been Yanggaw (2008). It’s by Richard Somes, it’s an Ilongo film about a yanggaw—Ilongo for a newly-turned aswang. This film is what I mean when I say what draws me to a story is the humanity in it. Because more than just being a story about somebody who just became an aswang, it’s also a family drama.

Photos courtesy of Yvette Tan (unless specified).