Putting on rose-colored glasses can feel naïve in an age of pressing problems, but perhaps it’s the salve we need to savor life and endure its hardest seasons.

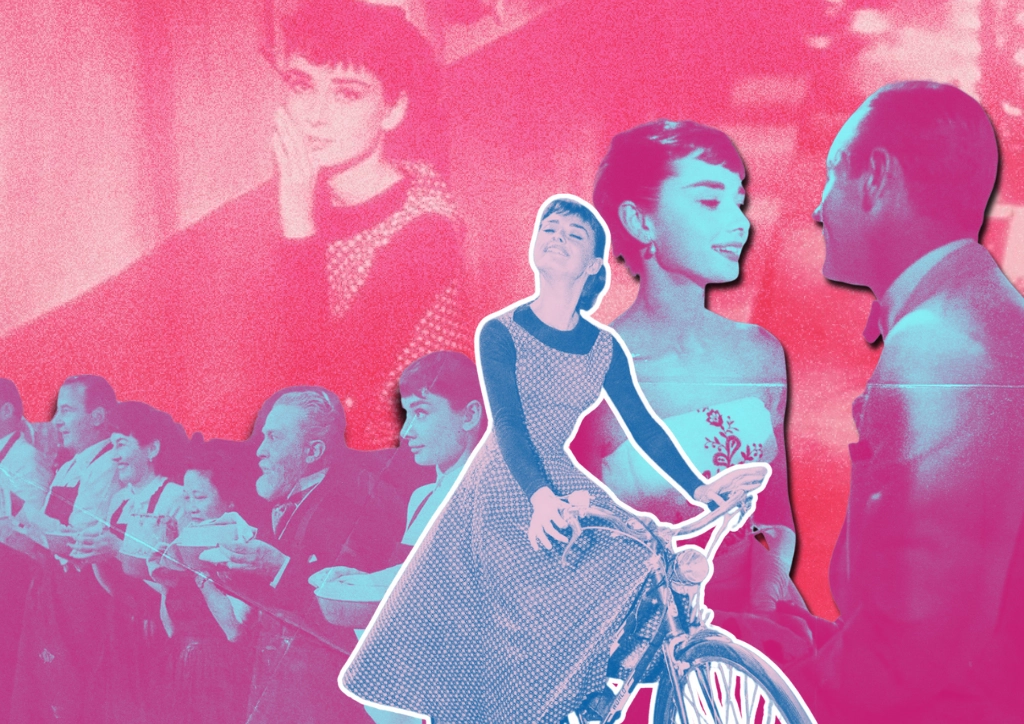

“It is late at night, and someone across the way is playing ‘La Vie En Rose.’ It is the French way of saying ‘I’m looking at the world through rose-colored glasses’…and it says everything I feel,” writes the titular character of 1954’s Sabrina in a letter. “I’ve learned many things, father. Not just how to make vichyssoise or calf’s head with sauce vinaigrette, but a much more important recipe: I have learned how to live. How to be in the world and of the world, and not just to stand aside and watch. And I will never, never again run away from life…or from love, either.” This is what I return to when I think about—and defend—the romanticized life: not as a needless delusion, but as, in trying times and in the stillness of quotidian moments, a necessary perspective

That this quote comes from Sabrina Fairchild—the shy, insecure, and, yes, suicidal daughter of a chauffeur hopelessly in love with the son of her father’s wealthy employers—is crucial. We’re not talking about a woman steeped in confidence or aflame with a lust for life. We’re talking about one who, in the wake of heartbreak, tries to end it all. What more is there? she asks. Plenty, the world replies, but she doesn’t see it until an old baron teaches her to step out of the shadows and become the main character of her own story.

READ ALSO: Let’s Be Terrible At The Things We Love

What Does It Mean To Romanticize?

You could call Sabrina’s situation melodrama (over an irresponsible man, no less!), but what if it was never really about the guy? There’s no need to read between the lines; it’s exactly as she says. It’s about learning to find and fall in love with the magic of the everyday—especially when the mundane promises nothing special, and may even feel bleak, because these are the moments when imagining something more becomes not just a way to survive, but to flourish.

By the film’s midpoint, our heroine returns transformed, changed by a simple yet seismic shift in perspective. Stepping out of the shadows, she no longer waits for life to happen; she coaxes beauty from whatever she has, and in turn, draws it back to her.

You could call it, as we say now, a kind of “manifesting”—optimism spoken aloud, shaping reality. But romanticization is its own kind of animal: a daring softness with an almost experiential element to it, one more reliant on spinning elaborations than simply viewing the glass as half full. It’s imagination in its most dynamic, alive form. The growing tendency to reach for it today is, in itself, telling of the times we live in.

Why Do We Crave The Romanticized Life?

The act of romanticizing isn’t particularly new. The Romantic movement of the late 18th to early 19th century could be called its precursor and catalyst: an aesthetic shift that valued emotion, creativity, imagination, and, as the name suggests, a “romantic” view of life. It was a direct rebellion against the industrial system and the scientific rationalism of the Enlightenment.

In the article “The Mundane Thrill of ‘Romanticizing Your Life’,” writer Christina Caron points out that the phrase “romanticize your life” became more ubiquitous during the pandemic era—and it doesn’t take much to figure out why. Undoubtedly one of the most harrowing periods of modern history, life suddenly felt stilted. Cooped up at home and grappling with the risk of a deadly contagion, we were forced to confront mundanity in a kind of Groundhog Day loop. And so, we did what we could to reclaim some semblance of control, even when, or precisely because, we couldn’t change our circumstances overnight.

Today, romanticizing life shows up everywhere, from social media feeds to late-night conversations with friends. “It’s giving main character energy,” someone will say, or you’ll turn the daily MRT ride into a scene from Before Sunrise in your head, even if the reality feels more like being stuffed into an anchovy tin.

A windswept stroll through the park can make you feel like one of those women in period dramas, taking a thoughtful walk to soothe their melancholia. Sipping coffee in an al fresco café, with shades and a cute jacket, makes you feel cool and mysterious—even though you’ve sprinkled croissant crumbs all over yourself (but that’s not the point of the exercise).

Rain-soaked streets are a musical number waiting to happen: you can choose between being Tom Holland lip-syncing Rihanna’s “Umbrella,” Don Lockwood splashing through puddles in Singin’ in the Rain, or Éponine waking up all of France with “On My Own” in the divisive Les Misérables film (if dramatized misery is your idea of soothing catharsis).

Going back to the Romantic movement, there’s nothing particularly rational about romanticizing life. It’s an inherently sentimental, saccharine act, and we live in a world where that kind of softness is often secondary. Some argue that romanticizing is just microdosing delusions of grandeur, a naïve and unserious practice that leaves you detached from reality. And why shouldn’t they? We live in difficult times: wars, a worsening climate crisis, governments that fail their citizens, people starving, killing, dying. What is there to be happy about? Wake up and commiserate. There’s truth in that.

There is a fine line between being tone-deaf and carving out an inner world of happiness from what you’ve been given, or what you’re privileged to have. We should, in our own ways, commit to actionable practices that make this world a better place, rather than live purely in our heads. But just because one thing is true doesn’t mean the other is useless or even harmful.

The Romanticized Gaze: Delusion Or An Act Of Care?

Ultimately, I’m of the belief that romanticization is a double-edged sword. Indulge in it too much, and you can tip into a navel-gazing echo chamber. But deny it, and you lose yourself in the toil of our messy world.

There’s something childlike about the practice of romanticizing life, and maybe that’s why some people think we shouldn’t make space for it in adulthood. Recall how your parents told you those little, magical white lies: they were your first brush with romanticization. Santa Claus is real; he gave you that gift and wrote you that letter in silver ink made of glittering, permanent snow. That money under your pillow was from the tooth fairy. That’s not a spoonful of mushy vegetables, that’s an airplane, or a choo-choo train. Did you hit your head? I’ll give it a kiss to make it better. See? All gone. And we believed these things because they expanded what we thought was possible, transformed the ordinary seconds and minutes into a sweet memory.

“Life is short and the world/is at least half terrible, and for every kind/stranger, there is one who would break you,/though I keep this from my children. I am trying/to sell them the world,” writes Maggie Smith in one of my all-time favorite poems, “Good Bones.” I think it sums this sentiment up better than I ever could. She ends it with this: “Any decent realtor,/walking you through a real shithole, chirps on/about good bones: This place could be beautiful,/right? You could make this place beautiful.”

We’re always made to choose extremes: if you romanticize, you don’t care enough about reality; yet if you dwell too deeply on the world’s problems, you risk losing your sanity. There’s a reason you can only consume so much bad news before feeling chest-achingly overwhelmed. Balance is necessary, and we can’t fault anyone for ploughing through life by having the audacity to find wonder in the unremarkable and even the ugly.

Romanticization, to my mind, isn’t just a tool for surviving reality: it’s also a way of reminding ourselves that, even when life takes so much, we can still be moved by what remains and shape it into something real enough to no longer need imagining.