As Steven Spielberg’s Jaws celebrates its 50th anniversary, we look back at the making of the pivotal film and how it unexpectedly became a pop culture phenomenon in the hands of a 26-year-old director.

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is a film so beloved and enduring that it continues to resonate as one of the most influential motion pictures in history. While fascination with the movie (and its famously troubled production) has never faded, interest is surging again as it celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2025.

In the upcoming documentary Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story (set to stream on Disney+ starting July 11), Spielberg and his team at Amblin Entertainment, including his longtime friend and biographer Laurent Bouzereau, who directs the film, revisit the behind-the-scenes chaos, creativity, and determination that brought Jaws to life.

Ahead of the documentary’s release, Lifestyle Asia revisits the conception, production, and cultural impact of Jaws: an unlikely smash hit that not only invented the modern summer blockbuster, but also marked a turning point in Hollywood history—ending the era of New Hollywood and, despite its massive commercial success, initially dividing critics and the industry alike.

READ ALSO: What Watching Every Steven Spielberg Film Taught Me About Life

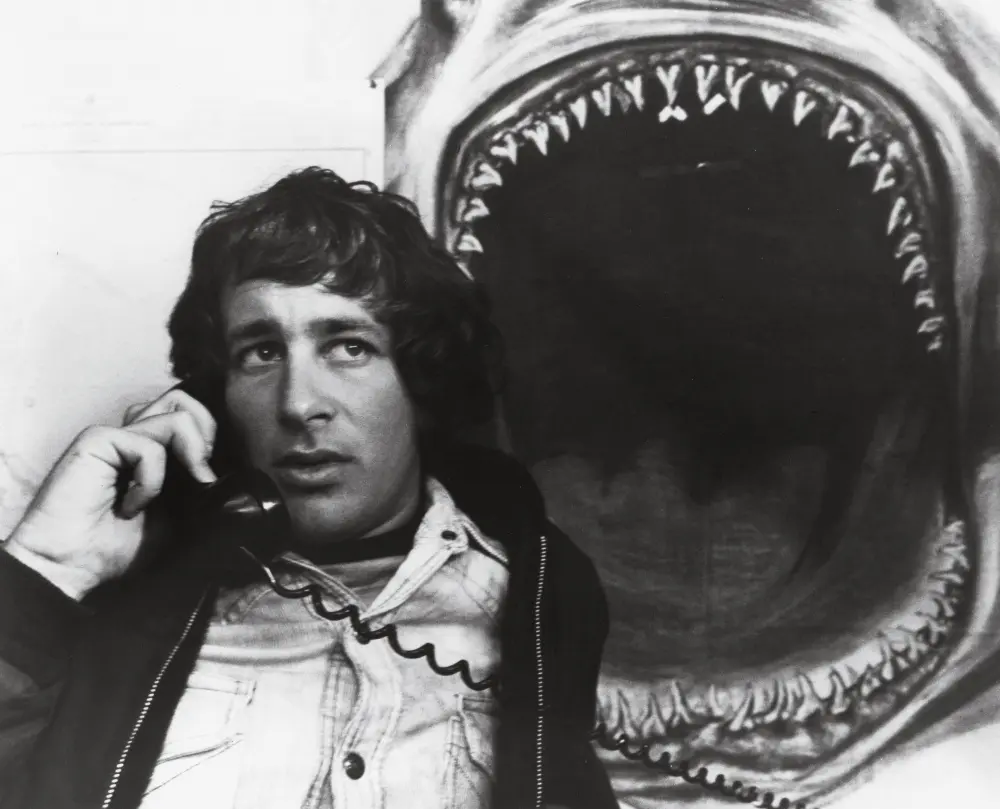

Steven Spielberg, Boy Wonder

In 1968, a 21-year-old Steven Spielberg moved to Hollywood with dreams of becoming a film director, driven by nothing but his love for cinema. His big break came when he impressed Universal Studios’s then-Vice President, Sidney Sheinberg, with a short film he had made at home with friends. Recognizing Spielberg’s potential, Sheinberg offered him a seven-year contract with the studio. Spielberg’s first professional gig was directing Hollywood legend Joan Crawford in the made–for-television film Night Gallery.

He followed this with other TV projects such as episodes of Columbo and Marcus Welby M.D. Impressed by his work ethic and dynamic visual style, Universal assigned their promising new director four major television films—the most notable being 1971’s Duel, which told the story of a psychotic truck driver relentlessly pursuing a man down a long stretch of highway. The film showcased Spielberg’s natural flair for suspense and storytelling, transforming what was essentially a simple car chase into something gripping and cinematic. Duel became a surprise hit, earning praise from both critics and audiences. Its success gave the studio the confidence to green light Spielberg’s first theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express.

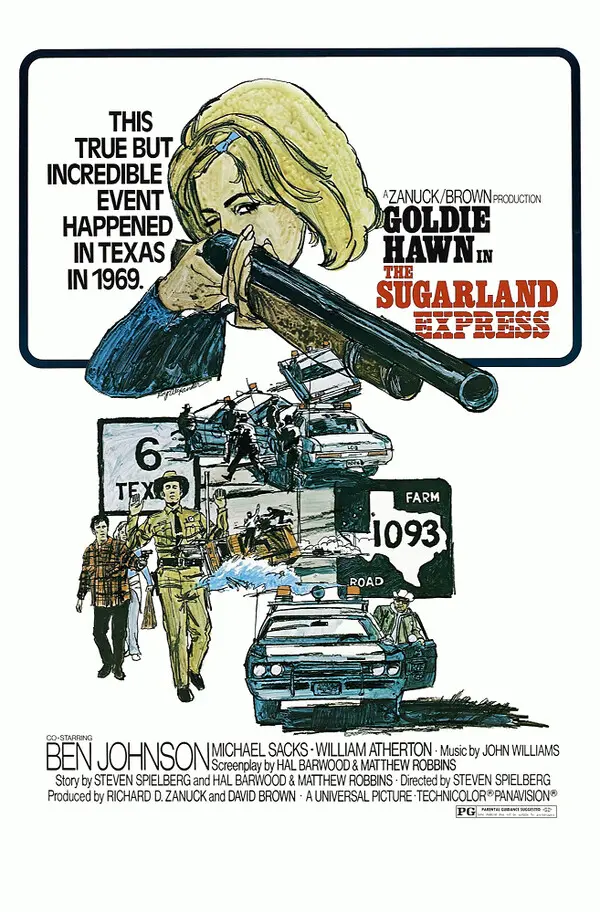

The Sugarland Express stars Goldie Hawn as a convicted felon who breaks her husband out of jail to retrieve their son from foster care. Their cross-country journey turns chaotic when they take a police officer hostage. Much like Duel, The Sugarland Express unfolds as an extended car chase, once again highlighting Spielberg’s talent for crafting dynamic and suspenseful action sequences. The film ultimately earned Spielberg and co-writers Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins the Best Screenplay award at the 1974 Cannes Film Festival.

Meanwhile, in America, The Sugarland Express received mixed to middling reviews. Famed critic Pauline Kael wrote: “The Sugarland Express is like some of the entertaining studio-factory films of the past (it’s as commercial and shallow and impersonal), yet it has so much eagerness and flash and talent that it just about transforms its scrubby ingredients. The director, Steven Spielberg, is twenty-six; I can’t tell if he has any mind, or even a strong personality, but then a lot of good moviemakers have got by without being profound. He isn’t saying anything special in The Sugarland Express, but he has a knack for bringing out young actors, and a sense of composition and movement that almost any director might envy.”

Kael’s review neatly captured what many critics would continue to say about Spielberg for years to come: that he was “entertaining” but “shallow,” “commercial” yet “impersonal,” “talented” but “not profound.” Despite the mixed critical response, The Sugarland Express performed impressively at the box office, earning four times its initial budget, much to Universal’s delight. Suddenly, the 26-year-old boy wonder director was a hot commodity… and he was just getting started.

A Famously Troubled Shoot

Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws landed at Universal Studios almost by accident, when producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown stumbled upon the manuscript before it was even published. Recognizing the material’s commercial appeal, they bought the rights on a whim, and quickly got to work on a screen adaptation. Spielberg, who had just worked with the producers on The Sugarland Express, saw the book at their office and asked if he could read it.

In an essay titled “Jaws: The Groundbreaking Summer Blockbuster that Changed Hollywood, and Our Summer Vacations, Forever,” writer Sven Mikulec goes in-depth with Spielberg’s eventual involvement. He writes: “Noticing certain thematic parallels with his highly praised TV debut film Duel—the fact the story was about ordinary people battling dangerous, unreasonable predators—Spielberg expressed his desire to direct the film. His wish came true as Zanuck and Brown convinced the studio that Spielberg’s relative inexperience might bring the freshness such an unprecedented project just needed.” Mikulec further notes that both the producers and their director were “very concerned” about “the film’s potential success,” given the challenges of shooting a story centered on a man-eating shark. Nevertheless, they set their doubts aside and moved forward with production.

What followed, however, was a famously troubled shoot. Spielberg began filming without a finished script. When the original screenplay by author Peter Benchley was deemed unsatisfactory by the studio, the director took it upon himself to make revisions. Eventually, screenwriter Carl Gottlieb was brought in to assist him, and the two would spend their evenings writing pages to be shot the very next day. Adding to the production’s complexity, Spielberg insisted on filming at sea, off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, rather than using a controlled studio tank on the backlot.

“I was naïve about the ocean, basically,” he told Ain’t It Cool News in a 2011 interview. “I was pretty naïve about mother nature and the hubris of a filmmaker who thinks he can conquer the elements was foolhardy, but I was too young to know I was being foolhardy when I demanded we shoot the film in the Atlantic Ocean and not in a North Hollywood tank. But had I to do it all over again I would have gone back to the sea because it was the only way for the audience to feel that these three men were cast adrift with a great white shark hunting them.”

The shark rarely worked as intended, causing endless frustration for the cast and crew throughout the production. The mechanical props, nicknamed “The Bruces” during filming, were designed by legendary special effects artist Robert A. Mattey, best known for creating the giant squid in 1954’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. While the shark’s appearance was convincingly menacing, operating it proved to be a constant and costly challenge for the filmmakers.

“The Bruces were continually damaged by the harsh salt water during filming,” states one writer from the Central Rappahannock Library, in a July 2021 article titled “Summer Movie Magic: A History of Blockbuster Films.” “At one point, the mechanical arm the shark was suspended from broke off, dropping a Bruce right to the sea floor.”

Faced with constant technical problems, Spielberg was forced to troubleshoot quickly. The production was already months behind schedule, and the budget had nearly tripled. Under mounting pressure from the studio to deliver the film, he chose to continue shooting scenes without showing the shark at all. “I felt like Alfred Hitchcock,” Spielberg told Ain’t it Cool News. “When I didn’t have control of my shark it made me kind of rewrite the whole script without the shark. Therefore, in many people’s opinions the film was more effective than the way the script actually offered up the shark.”

If you’ve been living under a rock for the last five decades, here’s a quick recap of the plot of Jaws: Roy Scheider plays Brody, the police chief of Amity Island, a small beachside community off Long Island. When a great white shark finds its way into the island’s waters, the townspeople—and especially the hardheaded mayor—refuse to close the beaches, fearing economic collapse. With the help of a young marine biologist (played by Richard Dreyfuss) and a tough seafarer (Robert Shaw), Brody sets out to hunt the shark before more lives are lost.

Watch any Jaws making-of documentary, and you’ll see just how tense the set truly was. In nearly all surviving behind-the-scenes footage, Spielberg, while trying to stay upbeat, appears visibly distressed. In numerous interviews, including one conducted at the premiere of the upcoming documentary Jaws @ 50, he admits how unprepared he felt during filming and how he genuinely believed Jaws might be the last movie he’d ever make. Yet despite delays, equipment failures, and endless logistical nightmares at sea, production finally wrapped in October 1974.

The Summer Of Jaws

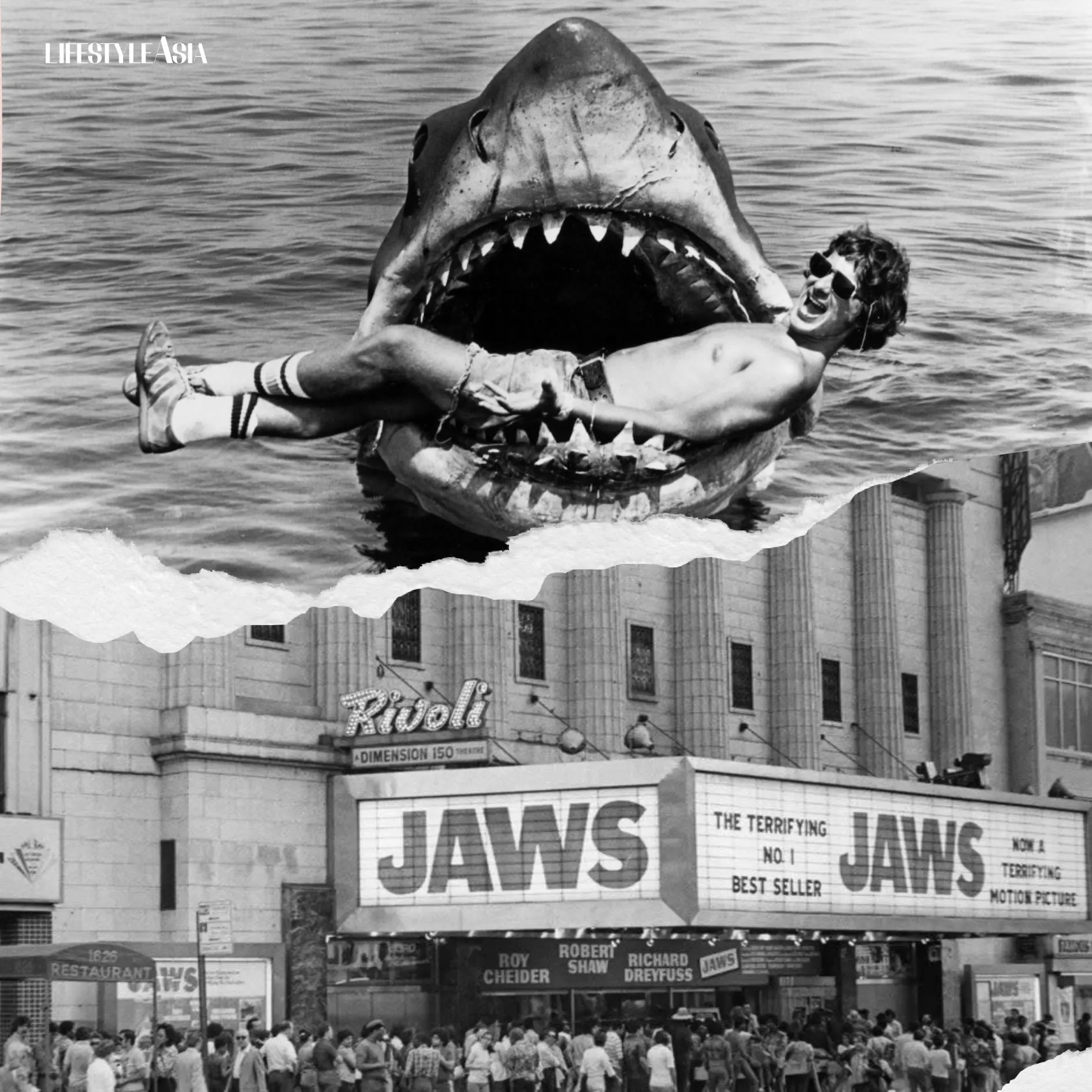

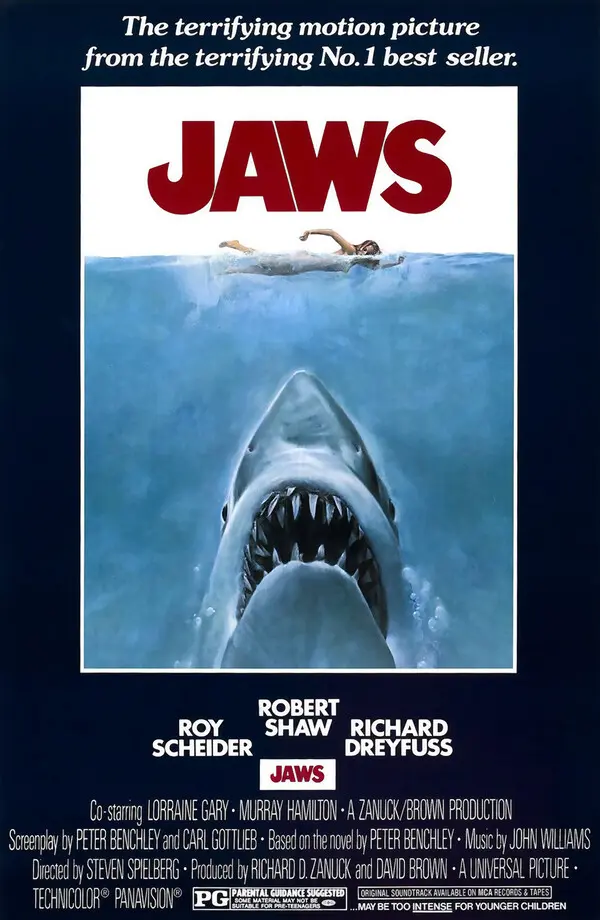

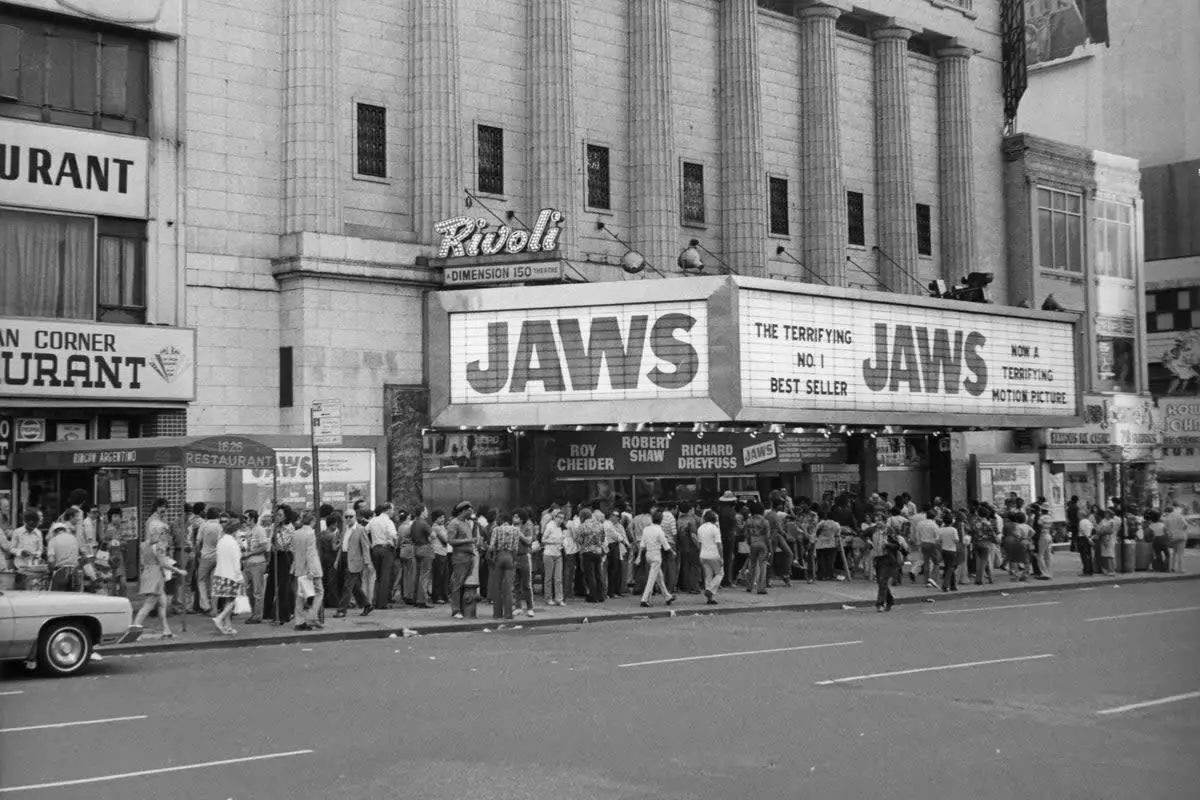

The summer of 1975 would come to be known as The Summer of Jaws. After an early screening, studio executives immediately knew they had a massive hit on their hands. They launched what was, at the time, the most ambitious marketing campaign Hollywood had ever seen. Copies of the novel were mailed to key tastemakers, money was poured into official Jaws merchandise, the press was courted with nationwide media tours, and millions were spent on 30-second TV spots that aired during primetime in the three days leading up to the film’s release. While such strategies are standard today, they were groundbreaking in 1975.

The studio also designed a new distribution model that would change standard movie practices forever. They opened Jaws in over 400 theaters, at a time when most films would premiere in a single location for three months before slowly expanding to other cities. The effort paid off. In just 78 days, Jaws dethroned The Godfather as the number one movie of all time. After 14 straight weeks at the top of the box office, Spielberg’s once-troubled film became the first movie to gross more than $100 million. It would go on to earn nearly half a billion dollars in cinemas around the world. Not bad for a film that only cost $9 million to make.

One of the major factors behind Jaws’ s success that year was its summertime release. Before the 1970s, the warmer months were considered the worst time to go to the movies, largely because theaters didn’t have air-conditioning. During this period, studios would offload their lower-quality films, saving their more prestigious projects for the end of the year—partly because the weather was cooler, and partly to align with Oscars season. Even The New Yorker’s renowned critic Pauline Kael would take summers off.

However, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, as more and more theaters were equipped with air-conditioning, studios saw a major opportunity to boost box office earnings. Jaws capitalized on this brilliantly. Audiences were not only more comfortable in cool, dark theaters: they were also too terrified to go near the water after witnessing the film’s brutal shark attacks.

Sven Mikulec writes, “The same summer it came out, the United States recorded a visible decrease in the number of people enjoying themselves on American beaches, while at the same time the number of phone calls to police regarding possible sightings of sharks rose drastically.” This led many people to see the film a second or even third time—choosing the safety of a cool theater over a swim in the ocean. And with that, the modern blockbuster was born.

Surprisingly, the success of Jaws also marked the beginning of the end for the New Hollywood movement that Spielberg had once been part of. Emerging in the late 1960s as the old studio system was fading, New Hollywood encouraged young filmmakers like Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola (among others) to create a new kind of cinema: something grittier, more personal, and artistically daring. This led to a renaissance that produced some of the most enduring films in history, free from the restrictions of the Hays Code and the tight chains of major studios. However, with the massive box office returns of Jaws, studios started shifting back to the old ways, where big-budget productions promised big financial returns.

IndieWire’s Eric Kohn writes in his article “Critics Notebook: Putting Steven Spielberg on Trial”: “The popular history proclaims that Spielberg’s Jaws helped put an end to that streak in 1975, with the assistance of Star Wars two years later. Rejuvenating Saturday matinee appeal with a combination of shock, suspense and wild imagination, these movies showed that classic Hollywood formula could still translate into box office dynamite.” By 1980, after a string of major auteur-driven flops like Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, the New Hollywood movement had officially come to an end. The decade that followed was dominated by blockbusters from directors like Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, Ivan Reitman, and others.

Jaws As A Misunderstood Masterpiece

Despite the overwhelming audience reaction, Jaws and its director (who became an overnight sensation) were not fully embraced by the top critics of the time. To be fair, they didn’t trash the film, but many dismissed it as little more than a frivolous adventure romp, much like Pauline Kael had done with The Sugarland Express. While critics praised the film as a technical marvel, they criticized the young director for what they saw as an inability to bring his characters to life.

Charles Champlin of the LA Times wrote, “Young Steven Spielberg, who was the director, shows as he has before an uncommon flair for handling big action. He, and the script, are much less successful in the man-to-man confrontations than in the man-to-shark meetings. Intimacy is not yet his strength.” Vincent Canby of The New York Times said, “If you think about Jaws for more than 45 seconds you will recognize it as nonsense, but it’s the sort of nonsense that can be a good deal of fun if you like to have the wits scared out of you at irregular intervals… It’s a noisy, busy movie that has less on its mind than any child on a beach might have.” Molly Haskell was less forgiving, saying the film felt “like a rat being given shock treatment.”

Today, Jaws has been reevaluated by critics and recognized as the masterful classic that it is. Many consider it one of the finest films ever made. It’s amazing what time, and a solid reputation, can do for a movie. Still, the hesitation to fully embrace it extended to the Academy Awards, where Spielberg was notably snubbed for Best Director, despite the film receiving four other nominations, including Best Picture.

By the time the Oscars ceremony rolled around, Jaws took home three awards: Best Sound, Best Film Editing, and Best Original Score. We’ll never know the exact reason Spielberg was left out of the Best Director category, but we can certainly speculate. Based on the original reviews, Jaws wasn’t widely regarded as the artistic achievement of the year. It was seen as too “mindless,” too “fun,” too “commercial.” Compare that to the eventual Best Picture winner, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which not only tackled more “serious subject matter,” but was also a major box office success. The Academy’s directing branch is also famously auteur-driven. Spielberg was the new kid on the block, and they likely felt he hadn’t yet earned his stripes.

The idea that Spielberg was merely a “commercial director” with “no nuance in his films” haunted him for the next two decades of his career. Still, he powered through, creating crowd-pleasing films that captivated audiences around the world. Following Jaws (and the notorious flop 1941), the trifecta of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial helped shape modern pop culture into what it is today. While all three shared the commercial appeal of Jaws and were each nominated for multiple Oscars, none took home Best Picture or Best Director. Sadly, earning massive box office returns wasn’t enough—Spielberg simply wasn’t in Oscars’s “wheelhouse.”

By 1985, Spielberg began to move away from commercial blockbusters and ventured into more “prestige” dramas. He directed a film adaptation of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, widely regarded as his first “serious” work. Although the film was expected to earn him an Oscar nod, he was shockingly snubbed on nomination morning. He would finally break through with the Academy in 1993 with Schindler’s List, which explored the horrors of the Holocaust. Spielberg at last won the long-elusive Best Director Oscar, and the film also took home Best Picture. But that’s a story for another day.

Long before Schindler’s List, and decades before anyone would dare call him a legend, Spielberg had already changed cinema forever with Jaws. At just 26, he cemented his place as a force to be reckoned with, shaping pop culture not through heavy-handed messaging or arthouse tropes, but by tapping into pure imagination. Jaws wasn’t just a hit, it was a phenomenon that redefined what movies could be. It proved that a young filmmaker with guts, vision, and a camera could hold the entire world in suspense.

Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story will begin streaming on Disney+ this July 11, 2025.

Jaws (1975) is currently streaming on NETFLIX Philippines.

A version of this article was published in video format in the author’s YouTube channel. It has been re-written and updated as a tribute to “Jaws” on its 50th anniversary.

Banner photos courtesy of The Daily Jaws and Kinorium.com