From humble Alfredo pasta sauce to rubber gloves, trace how love gave way to enduring objects and artworks.

“There once was a very great American surgeon named Halsted. He was married to a nurse. He loved her—immeasurably. One day, Halsted noticed that his wife’s hands were chapped and red when she returned from surgery,” writes Sarah Ruhl in her play The Clean House. “And so he invented rubber gloves. For her. It is one of the great love stories in medicine. The difference between inspired medicine and uninspired medicine is love. When I met Ana, I knew I loved her to the point of invention.”

History is full of stories like these, both big and small: moments when someone cared enough not to stand idly by, but to create and leave behind a tangible memento born of love and devotion, one that outlives even its creator. In many cases, the stories behind these unassuming inventions and artworks ebb away, leaving only the thing itself, its mythology lost somewhere along the way. Still, if you look closely enough, dig a little deeper, you begin to notice the vestiges of these narratives woven into each object’s very fabric. So before Valentine’s Day comes around once more, let’s take a moment to consider these wonderful proofs of love.

READ ALSO: The Vanishing Language Of Nature

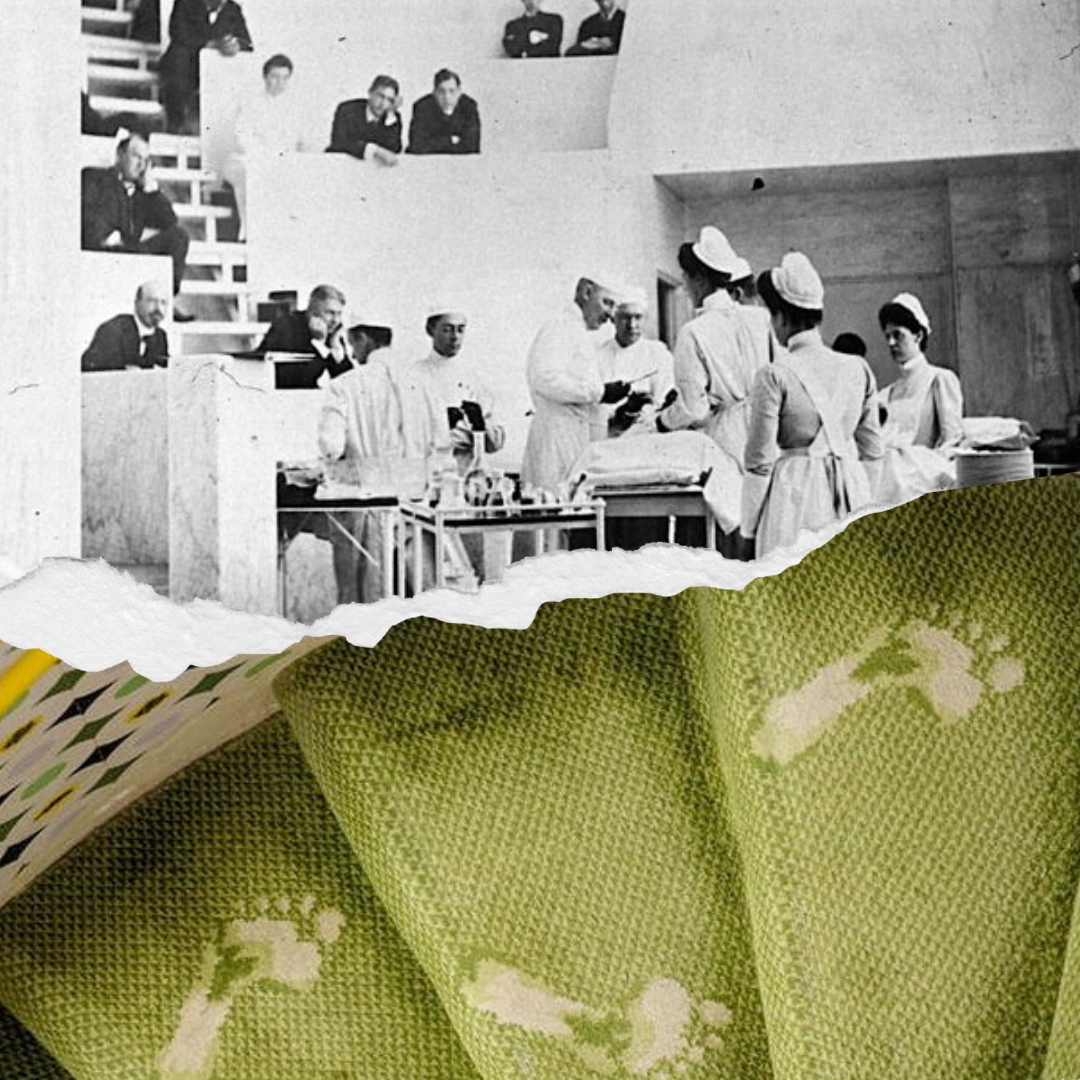

Rubber Gloves

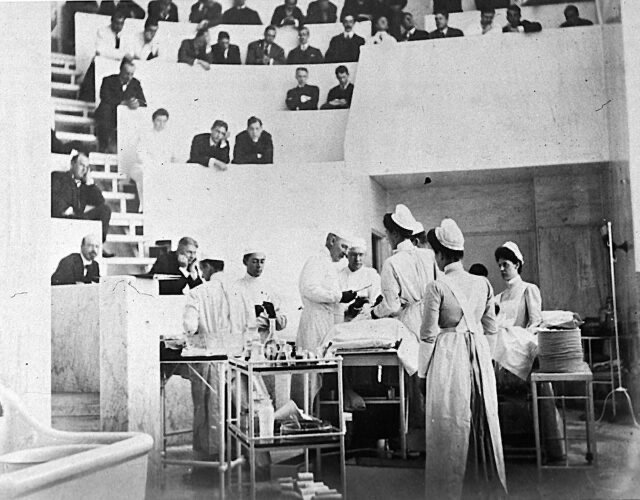

We’ll begin with the opening anecdote of this feature: the invention of rubber gloves. As Ruhl recounts, it started when famous American surgeon William Halsted took notice of a concern raised by his nurse, Caroline Hampton. She approached him to say she was planning to resign; her hands had become painful and raw from allergic reactions, a common affliction among medical staff at the time. Before operations, hands were routinely immersed in a strong antiseptic (carbolic acid) which often resulted in severe dermatitis.

Not wanting her to leave, Halsted asked the Goodyear Rubber Company to create a pair of thin, sterilized rubber gloves for her. He ordered more for himself and his staff and the rest, as they say, is history—and yes, Halsted and Hampton married just a few months after he gifted her that first pair. More than a product of his care and desire to keep her by his side, rubber gloves went on to revolutionize hygiene in medical practice, undoubtedly saving countless lives by preventing infections that were once frequent.

Alfredo Sauce

Pasta lovers are familiar with the creamy white Alfredo sauce that’s often topped on heaps of noodles, traditionally a mixture of butter, parmesan cheese, and pasta water (though some modern versions incorporate heavy cream). But what some may not know is that the beloved sauce was a fairly recent invention from the mind of Rome-born Italian chef and restaurateur, Alfredo di Lelio.

His namesake “fettuccine Alfredo” wasn’t just something he came up with while conceptualizing a menu, but what he felt to be a comforting necessity for his wife Ines in 1908. After giving birth to their eldest son, Armando, Ines felt incredibly weak; her husband decided to make a sauce that was nourishing yet easy to digest while she was recovering. She loved the new sauce so much, she asked Alfredo to put it in the menu of their quaint trattoria.

Years went by, and he opened a new restaurant, Via della Scrofa, where Hollywood stars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks took notice of the dish and praised it highly. Their endorsement led a slew of other stars to make Via della Scrofa a must-visit culinary stopover in Rome. From there, the recipe passed from husband to wife, and small kitchens to cookbooks across America, before eventually making it onto plates around the world.

Telephones

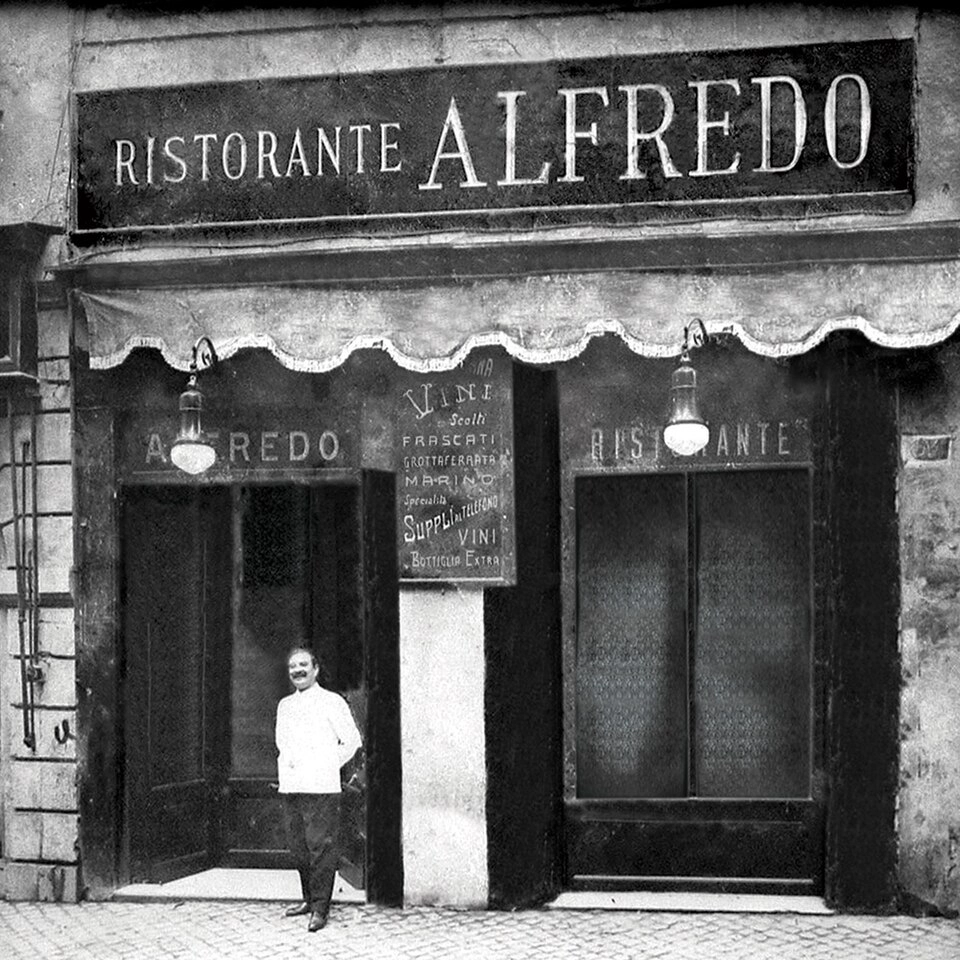

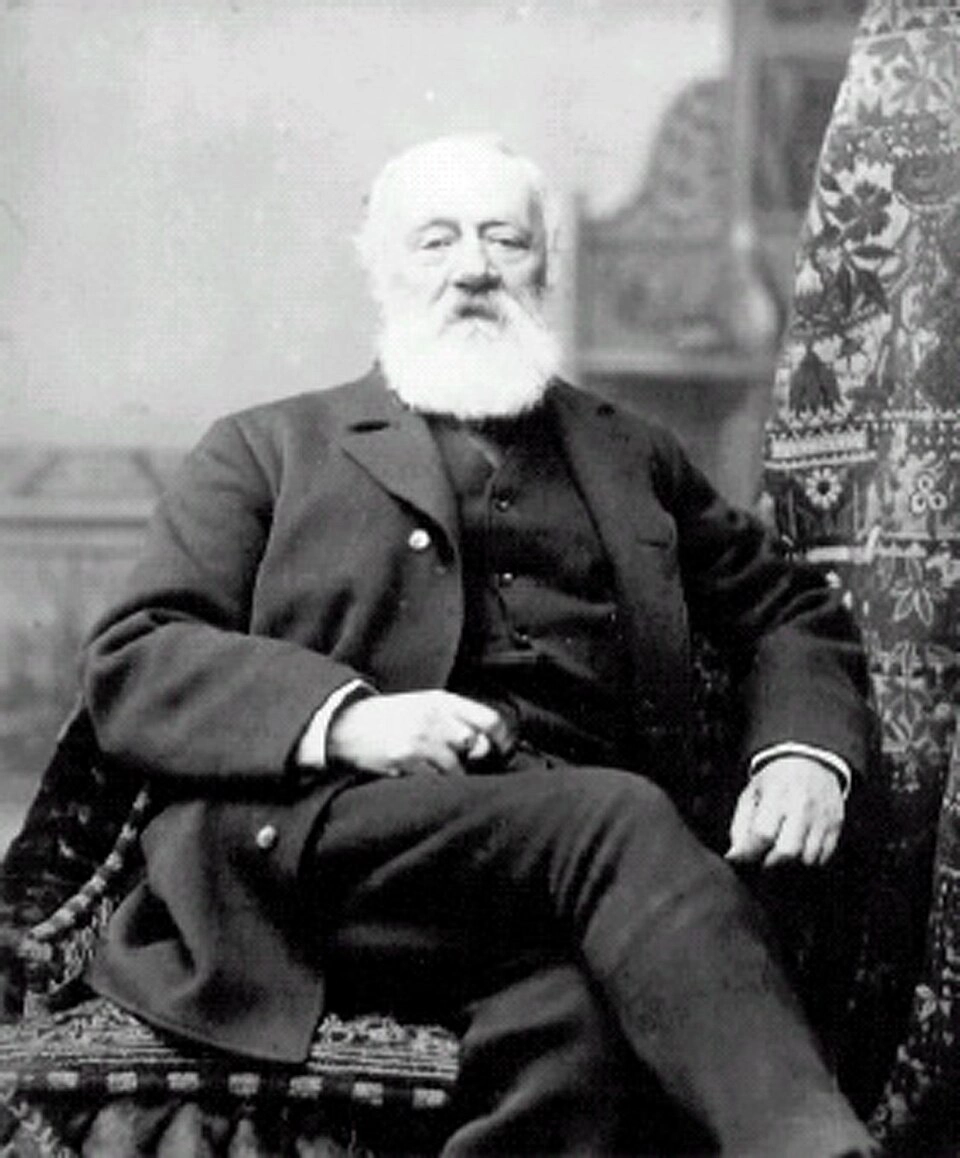

While Scottish immigrant Alexander Graham Bell is largely credited with the invention of the telephone, it was Italian immigrant Antonio Meucci who planted the seed that would become one of the world’s most important inventions. The engineer made a home in the United States with his wife, costume maker Esther Mochi, both of whom enjoyed some relative wealth from their respective occupations.

While Meucci was often investing in various experiments, it was his wife’s illness that would push him to develop a prototype of the telephone. An aggravated case of rheumatoid arthritis led Esther to be bedridden on the third floor of their home, unable to go out for the most part. Meucci decided to create a “speaking telegraph” for her that would allow them to communicate while she lay in bed.

He went on to develop more models, refining existing designs and carefully recording the results of his experiments in Meucci’s Memorandum Book, a 63-page volume that stands as definitive proof of his contributions to telecommunications. By the mid-1800s, he had arrived at designs he considered satisfactory and began searching for backers. Sadly, most investors failed to see the vision—one that would only be recognized much later, through Bell’s work.

Before that could happen, Meucci suffered a devastating accident when a boiler exploded on the ferry he was aboard, leaving him with severe burns across his body. During his recovery, Esther was forced to sell many of his models for a pittance, and they lived in relative poverty. Even when interest in his work resurfaced, he could afford to renew his patents only a few more times before they expired, ultimately allowing them to be issued to Bell. While it’s a bit of a sad tale, the United States House of Representatives did eventually pass a resolution in 2002 that honored Meucci’s work.

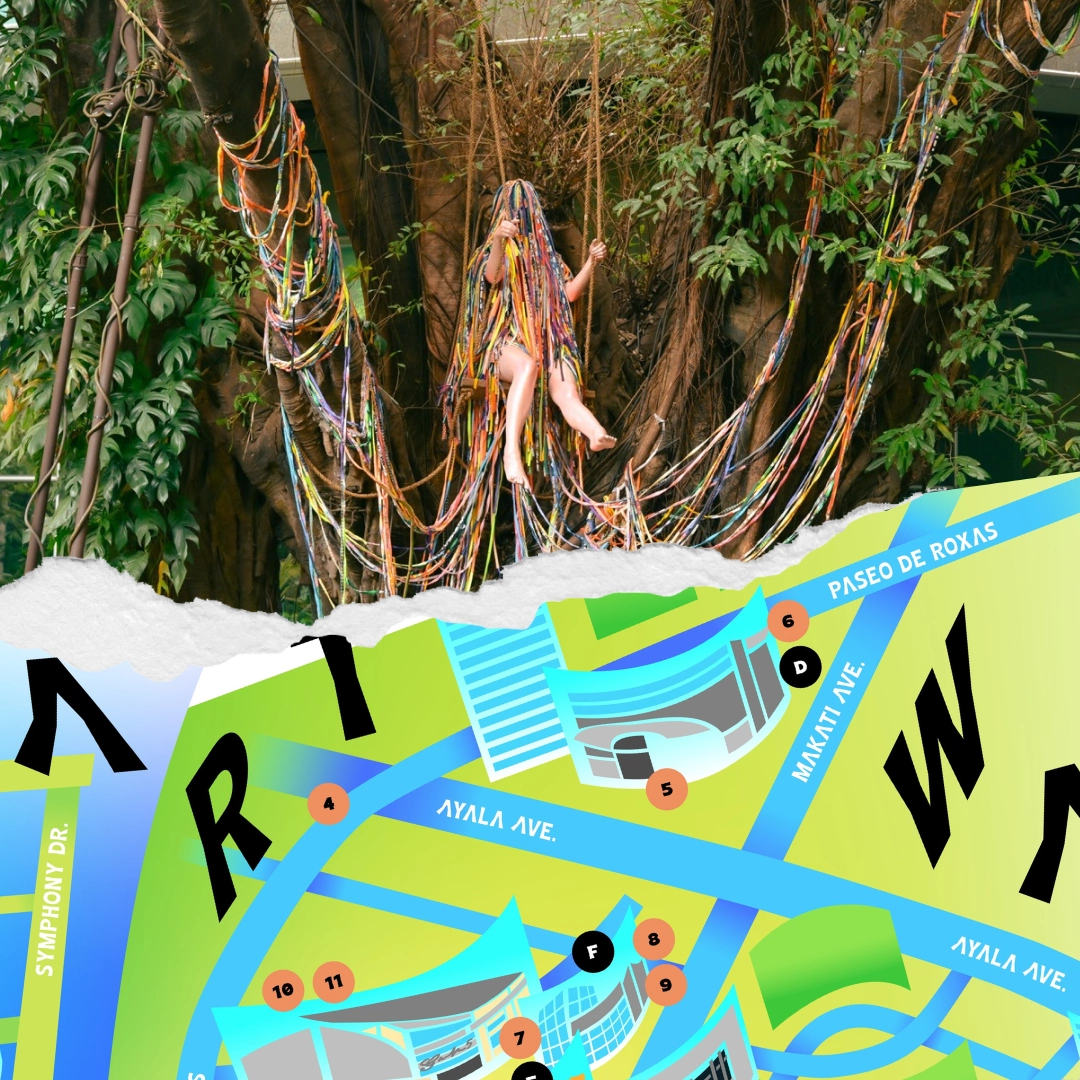

The Tilly Losch Footprint Carpet

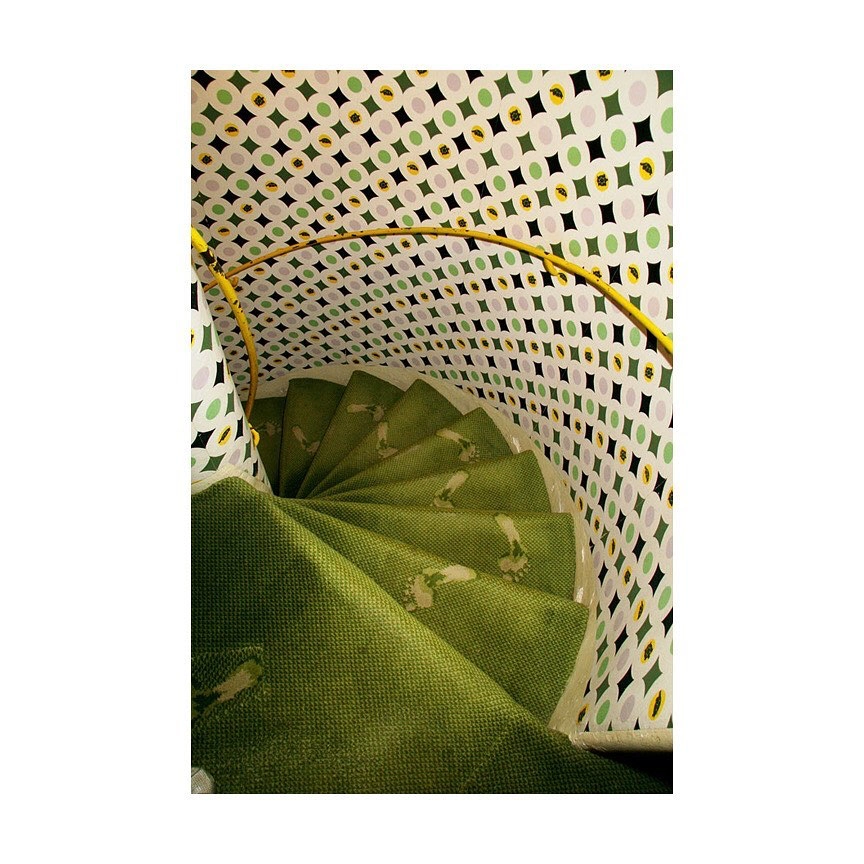

Moving beyond inventions and into lesser-known objects and works of art, we come to the stairwell carpet of British poet Edward James, millionaire and influential patron of the Surrealist movement. First situated at Monkton House on his estate—a home he shared with his former wife, dancer Tilly Losch—the carpet stands as a permanent reminder of their creative partnership and the admiration he held for her.

In the 1930s, Losch emerged from their bathroom and climbed the spiral staircase to their bedroom, her wet feet leaving prints on the soft fabric. James chose to have those fleeting marks sewn into the carpeting itself, creating a striking visual echo of her steps. Though the couple later divorced, the piece moved to his West Dean House (now a college), it remains a lasting token of love and memory.

The Grave of Fernand Arbelot

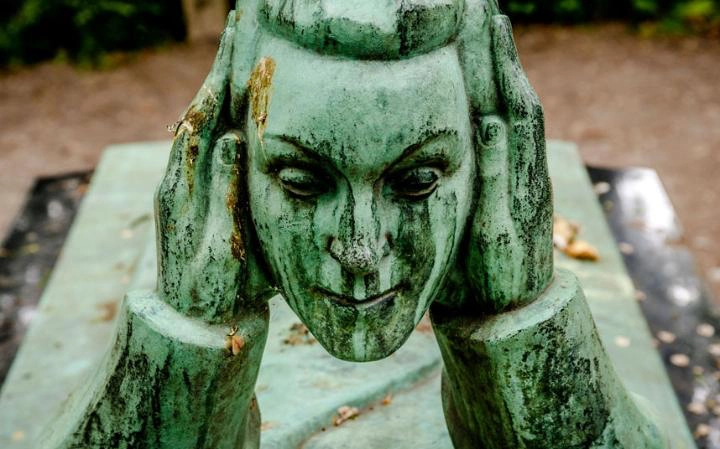

Cliché as it may be, some romances are said to transcend death itself. One object that embodies this idea is the grave of French musician and actor Fernand Arbelot, who died in 1942 during the German occupation of Paris. While he never achieved widespread renown and died in relative obscurity, Arbelot drew posthumous attention for the mysterious (and faintly macabre) design of his tomb.

Located in Paris’s Père-Lachaise Cemetery, the grave is marked by a sculpture of Arbelot reclining and cradling the severed head of a woman, who gazes back at him with a gentle grin. Though the identity of his beloved remains elusive, one grave-record site identifies her as Henriette Marie Louise Gicquel. Designed by Belgian sculptor Adolphe Wansart, the tomb bears an epitaph that reads: “They marveled at the beauty of the journey that brought them to the end of life.”