Film preservation is a relentless pursuit—futile yet necessary, it’s a defiance of time in the face of inevitable decay. In this special feature, we explore its past, present, and future in the landscape of Philippine cinema.

Most viewers rarely think about film preservation when watching a movie, even if they have seen phrases like “4K Restoration” or “Digitally Restored and Remastered” printed on DVD covers or in streaming captions. But the language doesn’t begin to capture the immensity of what they describe—or the hundreds of hearts, hands, and minds behind a single motion picture’s survival.

Why resurrect the reel?

“These are snapshots of years past that are brought back to life for a new generation,” shares Manet Dayrit, CEO of Central Digital Lab, a prominent player in the landscape of Philippine film restoration, in an exclusive interview with Lifestyle Asia.

Beyond entertainment, films are microcosms of entire histories and cultures, uniquely able to capture the spirit and movement of life in ways no other medium can.

READ ALSO: The Power Of Style: A Story Of The Barong Filipino’s Evolution

Celluloid Memories

“We have to really take good care of what’s left—everything, from the acknowledged masterworks of cinema to industrial films, home movies, anthropological films,” shares auteur Martin Scorsese, who founded the nonprofit organization The Film Foundation in 1990 to protect motion picture history, in a special feature on film preservation with Turner Classic Movies. “Anything that can tell us […] who we are, and who we’ve been, and who we’re becoming; the miracle of cinema is that it gives us that common image, that common idea, in time and motion, shot by shot.”

Scorsese’s statement on film being both identity and history is particularly salient in the Philippine context. As a country that relied on oral traditions for most of its precolonial history, the arrival of film marked a new form of record-keeping that captured the nuances of our lived realities to an unprecedented degree. Take Ibong Adarna (1941), a production from the influential but now defunct Filipino studio LVN Pictures, which adapted the 19th-century Filipino epic poem of the same name, transforming it into an iconic spectacle with its use of old Hollywood film techniques.

“By preserving the verisimilitude of contemporary life, it [cinema] has given us a mirror with which to view the past or a means to project ourselves into the future. Its widespread acceptance only proves its universal popularity,” states Filipino film scholar Nick Deocampo in his introduction to Keeping Memories: Cinema and Archiving in the Asia-Pacific.

Few things let us move through time as fluidly as films. Lino Brocka’s acclaimed Maynila, sa Kuko ng Liwanag (1975), offers an incisive portrayal of Metro Manila’s dark underbelly during the 1970s. Ishmael Bernal’s Himala (1982) offers a similarly raw and unflinching depiction of privation, shifting the focus away from the city and toward the barren, isolated fictional town of Barrio Cupang in the 1980s. Peque Gallaga’s Oro, Plata, Mata (1982) portrays the unraveling of two affluent haciendero families during World War II.

The reason why we can access and discuss these films is that a conscious decision was made to preserve them. The alternate scenario is one that’s painful to imagine: a loss so deep and irrevocable that we wouldn’t even know what we’re missing.

Rewinding History

The Philippines—having been on the receiving end of numerous wars, political upheavals, natural disasters, and colonial conquests—is no stranger to experiencing the frequent erosion and erasure of its narratives, both in a literal and figurative sense.

It doesn’t help that government institutions have been struggling with weak archival infrastructures. A lack of funding, bureaucratic red tape, and inconsistent policy implementation have prevented the creation of accessible, centralized archives for vital cultural and historical records. In a country where environmental conditions like high humidity and intense heat are antithetical to the preservation of delicate materials like film, the establishment of temperature and humidity-controlled facilities is crucial.

The history of film preservation is marked by the constant, tumultuous rise and fall of touchstone institutions—a journey that Bliss Cua Lim recounts in her book The Archival Afterlives of Philippine Cinema.

The first National Film Archives, formed under President Ferdinand Marcos in 1981, lasted only five years. What followed, according to Lim, was “25 years of state neglect:” a period that irreparably damaged the nation’s film heritage. In that vacuum, non-government group Society of Filipino Archivists for Film (SOFIA) kept the flame alive.

By 2011, the National Film Archives of the Philippines (NFAP) was revived and placed under the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP). Yet the archive continued to face challenges, especially after the FDCP de-prioritized it in 2016. Come 2018, the NFAP was rebranded as the Philippine Film Archive (PFA)—though by then, the pace of its preservation and restoration projects had greatly stalled.

The Motion Picture Division of the Philippine Information Agency (PIA-MPD) also had a prominent film laboratory and library, which was ultimately shuttered in 2004, reportedly due to “ineffective use of state resources” amid government costcutting and the transition to digital media.

Archival Silences

How much have we lost? The numbers are difficult to measure: cultural voids are often unquantifiable. Yet scholars like Lim have produced disheartening statistics. PIA-MPD’s library consisted of an “extensive but derelict” collection: 2,373 titles that encompassed experimental cinema, award-winning works, government media productions, and films from donor countries and agencies.

Lim adds that of the 350 films produced before World War II, only five complete feature-length Filipino films from the American colonial period remain (which feature the official national language, Tagalog-based Filipino). This doesn’t even begin to account for vernacular filmmaking from other regions like the Visayas—often considered “lost cinema”—with only a few titles still known to exist. These include Leroy Salvador’s Bisayan melodrama Badlis sa Kinabuhi (1969): set in the seaside town of Danao, Cebu, it follows a woman’s struggle to hold her family together as her husband spirals into alcoholism and infidelity.

The fate of Ibong Adarna (1941) is yet another example of the precarity of Philippine archival infrastructures. It’s the country’s last known nitrate film: a fragile and highly flammable medium widely used from the late 19th century through the early 1950s. When the film was restored in 2005, its contents were transferred to a safer cellulose acetate print (safety film). Yet no institution could store its nitrate duplicate negative—a backup of the original master copy—due to safety concerns. Either the facilities had shut down or were unwilling to house such a combustible hazard alongside other valuable materials, and so the copy was destroyed two years after its restoration.

Though the film remains available online (along with the ABS-CBN documentary Ang Pagbabalik ng Ibong Adarna, which chronicles its restoration), the destruction of its duplicate negative has left its future preservation uncertain; a sobering reminder of how ephemeral cultural memory can be once its physical traces disappear.

How One Institution Paved The Way

Despite the obstacles, film preservation in the Philippines has seen crucial wins, many of them thanks to private institutions like ABS-CBN. Filmmaker and scholar Clodualdo del Mundo Jr. even called the media giant the country’s “de facto national film archive,” and for good reason.

Since establishing its audio-visual collection in 1993, ABS-CBN became a major archival player, one of the first to build controlled environments for its film materials. In 2011, the ABS-CBN Film Restoration Project launched Sagip Pelikula, which has since rescued over 200 culturally significant titles—many available for free on YouTube.

However, its progress was disrupted by political headwinds. The 2020 franchise denial under former President Duterte limited resources and staff, forcing a shift from full restorations to simpler digital enhancements. Sagip Pelikula officially ceased operations in March 2025, following ABS-CBN’s earlier shutdown in July 2024. Thankfully, its work continues through Star Cinema and CineMo!, under the banner of the Sagip Pelikula Advocacy.

Being a large-scale endeavor, film preservation comprises several complex processes that are never done in isolation. It would take a separate article, or a book, to fully capture the amount of work involved. Much of Sagip Pelikula’s efforts were made possible through partnerships with international labs like L’Immagine Ritrovata (Italy) and Kantana Post-Production (Thailand), and most notably, local partner Central Digital Lab, which helped restore iconic titles like Oro, Plata, Mata and Himala.

Founded by Manet Dayrit, Central Digital Lab’s story is one that’s closely tied to ABS-CBN. Dayrit began at Roadrunner—a subsidiary of the conglomerate responsible for editing many of its films and advertisements—eventually acquiring its advertising arm and forming the post production company. Central Digital Lab remained a steadfast partner of Sagip Pelikula, helping the group restore 191 titles from its library while also working with other institutions like the Film Development Council of the Philippines, Viva Communications, Inc., and GMA Films.

The Unsung Heroes Behind The Screen

“Film preservation” is a loaded set of words that can mean something different to various professionals in the industry. Though for simplicity’s sake, we can borrow scholar Karen F. Gracy’s definition: “the effort to keep a film in a viewable form.”

Under the act of preservation are practices like conservation and restoration. Conservation usually requires no physical copying or alteration of a film, referring to any steps taken to ensure its care, including proper storage (which is why some scholars refer to it as “passive preservation”). Restoration, on the other hand, goes beyond safeguarding or copying a film: it’s an active, hands-on process that reconstructs it.

“When we do restoration, it’s fixing the impairments that are there, because these films have not been stored properly in the past, and there’s a lot of degradation happening,” Dayrit explains. “We try to bring back colors, fix scratches, and all the different impairments that might be there, to return the film to its original state.”

The restoration of Oro, Plata, Mata—Central Digital Lab’s first major project with Sagip Pelikula—began with a lengthy research and development process (10 years, to be exact). It took roughly 1,700 hours of work (more than 70 days), as Dayrit’s team had to search for missing scenes and remove mold that had developed on the film prints in their possession.

This was followed by the restoration of Himala: its process took a little over 500 hours—a considerably smoother endeavor, due in large part to the film’s shorter runtime. This, by no means, meant that the process was any less intricate.

The Art Of Fidelity

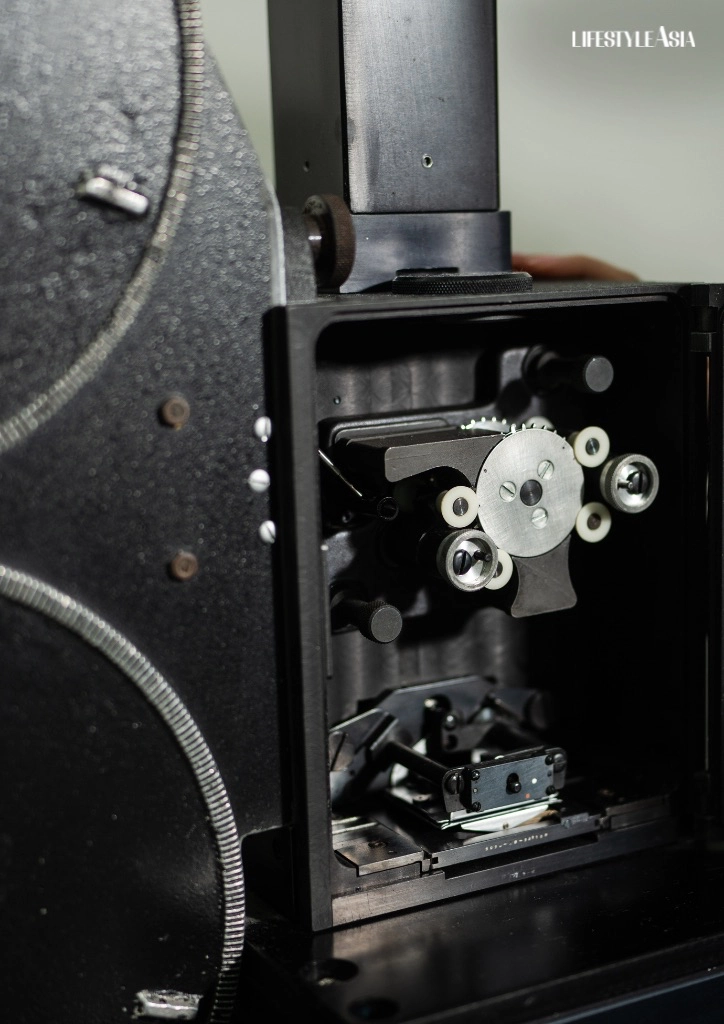

Dayrit breaks down the restoration workflow into digestible steps. First is locating and reviewing all available source material. “Sometimes, if we’re lucky, there’s more than one—whether it’s several prints or the negatives. We view and clean all of them, then see which versions can be used for restoration. Once we figure that out, we scan the film,” she explains.

One common sign of damage is “vinegar syndrome,” a chemical decay in old acetate film that gives off a strong acidic odor: an indicator of disintegration already underway. “It might take us some time to air it [the film] and clean it before we can even put it on our scanner,” Dayrit shares. “Sometimes the vinegar syndrome is so bad, a film might not even be usable for scanning.”

After scanning, the team begins restoration on two fronts: picture and sound. “Faded footage is common in older films, so we color correct them. And if they’re still around, we consult the original cinematographer and director to stay true to their vision,” explains Dayrit. Digital tools help automate dust and dirt removal, but manual work is still essential.

“Issues like scratches, mold, splice marks, or warps need to be fixed frame by frame,” she notes. On the audio side, the team eliminates unwanted noise such as pops, hisses, and wows (slow, wavering distortions caused by aging tape or damage).

Once restored, the film is exported into theatrical, streaming, or archival formats, depending on its intended use. For Dayrit and her team, one guiding principle remains constant: fidelity to the original work.

She recalls a moment with filmmaker and friend Carlos Siguion-Reyna (Hihintayin Kita sa Langit, Hari ng Tondo, Azucena). “He was watching one of his early films and said, ‘Oh my gosh, I want to change this.’ I told him, ‘No, you can’t. That was you back then. It’s a snapshot of who you were as an artist; now you can see how much you’ve grown!” Dayrit recounts, laughing at the memory. “I told him we will preserve the way it was, based on how you intended it to be at the time—not how you feel about it 30 years later.”

Fast Forward

Despite growing awareness, film preservation in the Philippines still faces steep challenges—chief among them, funding. Private institutions often fare better because they own the rights to the films they restore, making it easier to market and recoup costs.

The same can’t be said for many older titles, especially those in the public domain. “Investors will ask, ‘Why spend that much when people can pirate it?’” Dayrit explains. “But even then, we still need to preserve these cultural products.” She credits the Film Development Council of the Philippines and Philippine Film Archive for stepping in to handle many of these older, more vulnerable works—efforts that require ongoing government support.

New technologies like AI are increasingly being used to streamline restoration. While Dayrit and her team embrace these promising changes, which could greatly cut down costs and speed up processes, she also cautions against overreliance. To her, AI tools are like photo filters—too much, and you lose the essence of a work.

“When you make a film go through AI in its entirety, you end up having to undo some work. It tends to overdo things,” she explains. “We still need the human eye and touch to make sure we don’t overlook important details.”

For her, the most urgent task now is digitizing film materials before they deteriorate beyond repair. “Restoration is becoming more accessible,” she notes, “We’re hoping that even the institutions that don’t have the funds to restore their films fully will, at the very least, scan them so we can preserve them at the state they’re in, before they degrade completely.”

The Cyclical Act Of Love

One line from Karen Gracy’s book Film Preservation lingers: “Indeed, the physical structure of motion picture film carries within it the seeds of its own destruction.”

It’s a tragic statement: how can you persist when every fabric of your being insists otherwise? Film will always be frangible, whether it’s stored or used. When run through a projector, elements like heat, friction, and tension invariably cause wear and tear. The ever-changing landscape of media also exacerbates this sense of impermanence. “Digital” is not synonymous with “immortal,” which is why restoration is a never-ending endeavor.

“Resolutions are getting higher and higher,” Dayrit elaborates. “Technology changes so quickly, you have to keep doing research and development. You need to have redundancies, upgrading hardware, and constantly migrating material to a more stable format.”

In Lim’s The Archival Afterlives of Philippine Cinema, cinephile, curator, and archivist Teddy Co likens this situation to the Greek myth of Sisyphus: a cunning king who, after cheating death twice, is punished in the afterlife—made to push a massive boulder up a hill for all eternity. He never reaches the hill’s peak, condemned to watch the rock roll back down again and again. Philosopher Albert Camus once described Sisyphus as an “absurd hero” who exists to accomplish nothing. Those who work in film preservation understand his cyclical task more than anyone. Still, they continue to push the figurative boulder, defying the odds.

“I’ve been working in film for 30 years and I feel this is my giving back to the industry that I love,” Dayrit explains. She recalls seeing Himala playing on screen during the recent memorial of National Artist Nora Aunor (who played its main character Elsa), and remembers how she felt: grateful. “Thank god we were able to do that. Even with Nora gone, for years to come, new generations will appreciate her brilliance.”

Somewhere out there, people are experiencing the impossible. A budding filmmaker is learning all he can from a movie that should’ve been lost to time. A young woman is visiting a section of Manila that no longer stands. To ask why people continue the painstaking work of preservation is like asking why we attempt to make something out of our lives at all, even in the face of death’s inevitability.

Why does Sisyphus persist? Because the effort itself—that constant uphill climb—is where existence finds its meaning.

This article was originally published in our September 2025 Issue.

Photography by Kim Montes