Originally dismissed by critics as overtly schmaltzy and historically dishonest, The Sound of Music was never meant to endure. Yet 60 years later, its positive message, unforgettable songs, and lasting iconography continue to bring joy to new generations.

60 years ago, The Sound of Music premiered in the United States—and the reviews were far from glowing. Given its reputation as one of the most beloved films ever produced for the silver screen, you’d expect critics at the time to have sung it praises. Instead, Bosley Crowther, the tastemaker of The New York Times, dismissed it as “cosy-cum-corny,” while the famously exacting film critic Pauline Kael delivered an even harsher blow, calling it “the single most repressive influence on artistic freedom in movies.” Her review was so blistering that it cost her her job at McCall’s magazine, where it appeared.

Even famous writer Joan Didion lost her column at Vogue in 1965, after writing that The Sound of Music was “…more embarrassing than most [musicals], it’s only because its suggestion that history need not happen to people like Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer. Just whistle a happy tune, and leave the Anschluss behind.”

Didion isn’t exactly wrong. The Sound of Music does reduce the Nazi invasion of Austria to little more than a looming inconvenience within the von Trapp household. It also glosses over key historical truths about Maria and the famous family, opting instead for a romanticized version seen through rose-tinted glasses: a major reason why many Austrians take issue with the musical that made their country so famous.

So why? Why, after 60 years, does The Sound of Music remain so beloved by audiences worldwide, so much so that we still watch it year after year? Even here in the Philippines—a country hardly known for its arthouse and classic cinema scene—a remastered 4K version is getting an exclusive two-day run at SM Cinemas nationwide this September. Why are the hills still so alive in pop culture? Well, despite everything I’ve just mentioned, the truth is, the film is a classic that managed to capture lightning in a bottle.

The Very Complicated Sound Of Music

In the fall of 2016, I found myself in Salzburg, Austria, on vacation with my family. As a cinephile and lifelong fan of The Sound of Music, I was ecstatic to be there, fueled by the thrill of seeing those filming locations in person. Yes, Salzburg is famous for being Mozart’s birthplace, but for me, it’s first and foremost the city where an immortal movie was made. Mozart is great, of course, but The Sound of Music is something my whole family loves and shares. It was, in fact, the second DVD we ever owned at home, and one we watched on repeat.

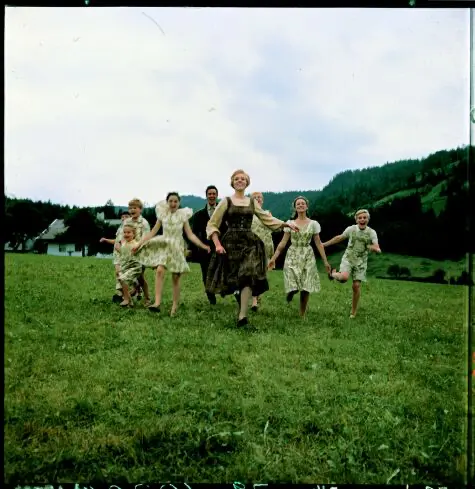

One morning, standing in the Mirabell Garden—the setting for the joyous finale of “Do-Re-Me”—I suddenly heard a voice. Someone had started singing the song. Then, one by one, others joined in. I cringed. Sure, I love the movie, but…not thissss, not nowwww, I thought. Yet before long, my secondhand embarrassment melted away as the entire crowd belted out the Rodgers and Hammerstein classic from memory. In that moment, I realized the true power of the film: it unites people, no matter who they are or where they come from.

Later on, I was surprised to learn that the movie was not particularly embraced by Salzburg’s residents, despite the fact that it contributes significantly to their economy, drawing more than 300,000 visitors from around the world each year because of its connection to the movie.

In the 2012 documentary Climbed Every Mountain: The Story Behind the Sound of Music (available to watch for free on YouTube), filmmaker Christopher Walker and host Sue Perkins explore the film’s complexities, particularly the discomfort many Austrians feel toward it. They argue that the movie sugarcoats Austria’s relationship with the Nazi Party during the Second World War, overgeneralizing by portraying the country as broadly nationalistic and opposed to the Nazis. In reality, it was more complicated than that: a great deal of the population was generally supportive of Hitler’s ideologies.

Then comes the film’s historical inaccuracies concerning the von Trapp family. The movie musical is based on the 1959 Broadway production with a score by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, which, in turn, was adapted from Maria von Trapp’s 1949 memoir The Story of the Trapp Family Singers. Like most works translated into another medium, the writers of the musical took considerable creative liberties, shaping Maria’s story into the version we now know: a kindhearted nun leaves the Abbey to become governess to a strict, former army captain’s seven children. She falls in love with her wards, then with their father, and together they flee Nazi-occupied Austria before World War II. This is generally true—but also, not quite.

Climbed Every Mountain makes a compelling case by interviewing key figures connected to the von Trapp family, most notably Maria and the Captain’s two youngest children, Johannes and Rosemarie (born in America later, which is why they aren’t depicted in the film). Both assert that the classic movie gets a great deal wrong. Dates are scrambled and an important German priest named Father Franz Wasner—who helped hone their skills as performers, escaped with them to America, and lived with them for 20 years—is erased, and certain character traits are inverted.

According to them, the Captain was in fact soft-spoken and kindhearted, while Maria, though loveable in a quirky way, was actually stern and no-nonsense. She loved to sing, but she was also strong, ambitious, assertive, and instrumental in not only making the family famous as folk singers in America, but also in cultivating their image as mythic wartime survivors and cultural icons. Perhaps the most startling revelation comes from Rosemarie von Trapp, who believes her mother may have had an undiagnosed bipolar disorder.

Other documentaries available online—including a TV special by Diane Sawyer, produced to celebrate the film’s 50th anniversary in 2015—point out more historical inaccuracies. For instance, the over-romanticized ending depicts the von Trapps escaping Austria on foot as they climb the Alps to safety. In reality, the family left Salzburg one morning, after having been asked the night before to sing on the radio in celebration of Hitler’s birthday. As non-supporters of the Nazi Party, Captain Georg von Trapp, Maria, their seven children, and Father Franz woke up at 6 AM, walked five minutes to their local train station, boarded a train, and left for the Italian border. Eventually, they received visas for the United States and emigrated there, becoming a famous folk singing group called the Trapp Family Singers until they disbanded in the 1950s.

The movie version is the kind of romanticism that Hollywood often indulges in, and it tends to rub many the wrong way—especially European audiences, who are no strangers to grittier, more realistic films thanks to fewer censorship restrictions. The 1956 German film The Trapp Family, still a musical comedy, is widely regarded by scholars and historians as a more accurate account of the clan’s story. Nevertheless, it’s The Sound of Music that endures—for many reasons we’ll explore later.

READ ALSO: The Sound Of Salzburg: Mozart And Maria Von Trapp’s Hometown Is A Majestic Travel Destination

Hollywood Performs Its Magic

In the 1950s, movie musicals reigned supreme. The strong link between Broadway and Hollywood produced numerous big-budget adaptations of stage hits, immortalized on celluloid. 20th Century Fox, once trailing behind MGM’s Dream Factory in the 1940s, was finally catching up with its rival thanks to lavish roadshow productions of Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, starting with the 1956 hit The King and I and followed by South Pacific in 1958.

Musicals continued to thrive into the 1960s, especially after the phenomenal success of West Side Story in 1961. The film won ten Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and was both a box office sensation and a critical triumph, credited with modernizing the genre for a grittier decade. Then came My Fair Lady in 1964, Jack Warner’s opulent production that also swept the Oscars—though its triumphs were somewhat overshadowed by the controversial decision to pass over Julie Andrews, the original Broadway star, in favor of Audrey Hepburn and her undeniable box office appeal.

Yet The Sound of Music‘s journey from stage to screen already began a few years earlier, when the original Broadway production starring Mary Martin premiered on the Great White Way in 1959. Although the show itself had middling reviews due to what critics called its “schmaltziness,” it was a resounding success with audiences, earning five Tony Awards including Best Musical. Hollywood was eager to adapt the prestige production with Rodgers and Hammerstein’s pedigree—especially one with a thin thread of social commentary about the Nazis, which was fashionable in films of the era.

Fox studio head Richard D. Zanuck commissioned celebrated screenwriter Ernest Lehman to develop the project. Lehman, who had watched and enjoyed the show with his wife, was passionate about stripping away the sentimentality it was criticized for: he saw its potential to become more serious in subject matter. Lehman’s screenplay restructured the original musical considerably, expanding the Salzburg setting to take full advantage of the cinematic form. He also rearranged the songs to give the score a stronger thematic shape, deleted numbers he found unnecessary (two sung by the Baroness and her friend Max), and requested two new songs from Richard Rodgers (Hammerstein had passed away by 1960). In hindsight, Lehman truly shaped The Sound of Music into what we know and love today.

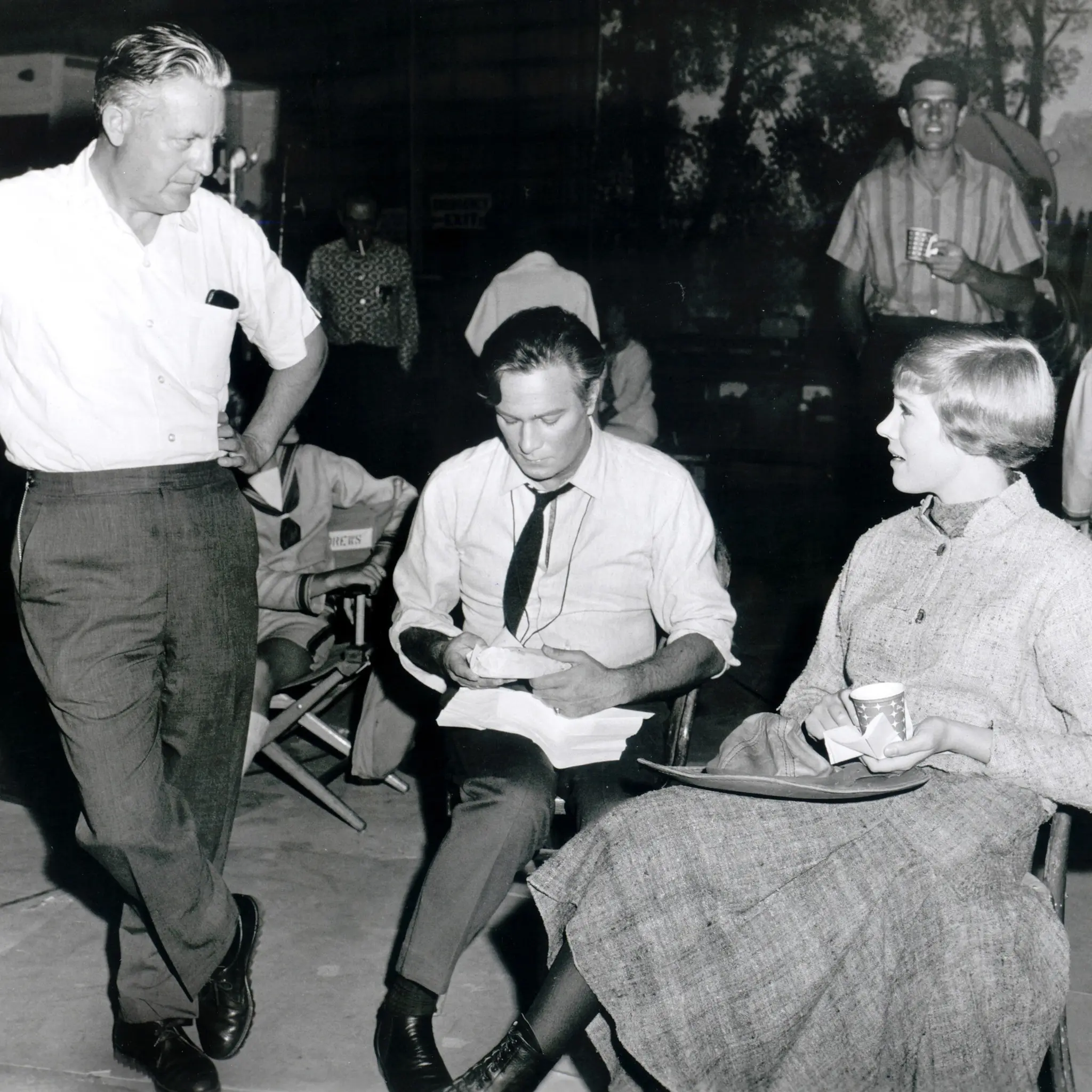

Lehman’s script attracted top talent, including Oscar-winning director William Wyler, who even went to Austria with the screenwriter to scout locations. However, due to a lack of enthusiasm for the subject matter, Wyler would eventually back out of the project. Lehman, in search of a replacement, then tapped his former collaborator Robert Wise, who had recently worked on West Side Story with him (a partnership that had earned Wise an Academy Award for Directing). Zanuck agreed he was the perfect choice for their new prestige project.

Though names like Grace Kelly and Doris Day were floated for the role of Maria von Trapp, Wise and Lehman soon realized that a newcomer named Julie Andrews was destined for the part. In 1963, Andrews had made only two films (both had yet to be released), but she was already the toast of Broadway. While searching for their Maria, the filmmakers were granted an early look at footage from Mary Poppins. Impressed by her charm and presence, they signed her before film stardom could whisk her away. Their instincts proved correct: Andrews went on to win the Best Actress Oscar for Mary Poppins, and her skyrocketing popularity played a major part in The Sound of Music’s eventual box office triumph.

For the pivotal role of Captain von Trapp, they cast Christopher Plummer: a serious, Shakespeare-trained stage actor who was reluctant to take the part. He found the role, and the film as a whole, to be overly sentimental and “gooey”. During production, he disliked the experience so much that he drank heavily during his downtime, was openly dismissive of the project, and for years referred to it as The Sound of Mucus. That said, the actor would soften his stance years later, coming to appreciate the film’s enduring charm and cultural impact. He also developed a lifelong friendship with Andrews, which lasted until he died in 2021.

Generally, production on The Sound of Music was about as challenging as one might expect for a project of such scale—especially since it was shot extensively on location—but nothing too outrageous or cursed (certainly nothing on the level of the legendary on-set chaos of Jaws or The Exorcist). The filmmakers faced their share of hurdles; but professionalism, hard work, and grit kept the production mostly on track.

Among the often-cited challenges were the difficulty of capturing the iconic opening shot via helicopter; a few minor accidents involving the child actors; and the constant rain in Salzburg, which caused repeated delays over a period of up to five weeks. Still, the cast and crew pressed on, and the set of The Sound of Music—Plummer’s moping aside—became a joyful, lifelong memory for Julie Andrews, the seven young actors playing the von Trapp children, and the rest of the filmmakers involved. If you’re interested in a more in-depth production history, I highly recommend watching the 1994 feature-length documentary The Sound of Music: From Fact to Phenomenon, which includes countless anecdotes from the cast and crew. It’s available to watch on YouTube for free.

Filming wrapped in September 1964, just three months before Mary Poppins was released in theaters and set to propel Julie Andrews to instant superstardom. Sure, Fox, Wise, Lehman, and the cast and crew knew they’d made something special in Austria, but they all moved on with their lives, returning to their respective corners of the world without knowing just how much of a cultural phenomenon the film would become. Within months, their lives would be transformed—and sixty years later, The Sound of Music continues to keep them in the public imagination.

READ ALSO: These 8 Musicals Should Be Hollywood’s New Obsession

Joy Is Immortal

The Sound of Music premiered on March 2, 1965, at the Rivoli Theater in New York City. As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, the reviews weren’t great. Critics felt the same way about the film as they did about the original stage show: they found it frivolous, overly joyous, and far too sentimental, with its singing nuns (and dancing Nazis to boot!). However, Fox wasn’t about to let their investment go to waste.

They couldn’t simply rely on the popularity of the stage production, though they were fortunate to have the newfound star power of Julie Andrews, who had become an international sensation just months earlier with Mary Poppins. Still, the studio needed insurance, and carefully planned every aspect of the film’s marketing and release. They brought in big-time publicity strategist Mike Kaplan to design striking trade ads and lasting iconography, much of which continues to be used in promoting the film today. And during production in Salzburg, they organized press junkets for American journalists—an effort that helped transform the release into one of the year’s most highly-anticipated cinematic events.

The film was also released as a traditional roadshow presentation: a common practice for prestige, big-budget films of the era, used to build hype through word of mouth. This meant it opened in a limited number of major city theaters with higher ticket prices and reserved seating, before gradually expanding nationwide. Four weeks into its limited engagement, The Sound of Music had already become the number one film at the US box office, despite playing in only 25 theaters.

By the time it was widely released in early April 1965, audience enthusiasm was soaring, and the film quickly became a pop culture tour de force. It went on to become the most financially successful film since Gone with the Wind in 1939 and remained in theaters for an extraordinary four and a half years, finally closing in 1969. By the end of its initial theatrical run, The Sound of Music earned approximately $286 million at the box office (about $2.5 billion in today’s dollars) against a budget of $8.2 million. That’s Avengers: Endgame numbers.

In the documentary From Fact to Phenomenon, the film’s producers speculated that, beyond its marketing strategy, the factor that truly fueled The Sound of Music’s box-office success was its remarkable return audience: viewers kept coming back for repeat showings. They also credited the score—memorable, accessible, and easy to sing along to—as a key contributor to the film’s enduring appeal.

This kind of victory—both as a box-office juggernaut and global pop culture moment—was too powerful for the film industry to ignore, especially those who had once dismissed the movie as a “silly little musical.” Despite tough competition from David Lean’s epic Russian romance Doctor Zhivago, there was little doubt that The Sound of Music would sweep the Academy Awards. Nearly a year after its wide release, the film took home five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. Many believe it might’ve claimed a sixth award, Best Actress for Julie Andrews, had she not won the previous year. Still, the film walked away with the top prize, and the “musical that could” immortalized itself in Oscar gold.

Sometimes, winning the Academy’s top prize is enough to secure a film’s place in history; but The Sound of Music had more going for it than the typical Oscar winner of its time. First and foremost, it was one of the most popular movies ever made—virtually everyone saw it. As a family film, it was welcoming, with an audience that spanned from young to old, ensuring no one ever felt out of place.

The Sound of Music is also a well-crafted piece filled with beautiful, iconic shots and settings; memorable songs that invite audiences to sing along; a sharp, family-friendly story (despite its artistic liberties); and uplifting themes that never feel too heavy. Fox recognized this and capitalized on its success—not only by keeping it in theaters for as long as possible, but also by turning its first American television broadcast into a national event. When it aired on NBC in February 1976, the network had to pay Fox a staggering $15 million just for the rights to show it. Today, they continue to regularly screen the film with Sound of Music Sing-A-Long events happening multiple times a year.

Beyond box office records and television ratings, the film’s true staying power lies in something far more intimate: the way it’s been passed down from generation to generation, across various families. The influence of our parents, who first experienced The Sound of Music with their own parents, is a big reason why the film continues to endure in 2025. Many millennials and older Gen Zers first discovered it through them, and continue the viewing tradition. Thanks to the power of VHS, then DVD, and now streaming (the film is currently available on Disney+), it continues to delight audiences of all ages, as long as they know it exists and have access to watch it.

Ultimately, the film belongs to that rare group of movies that feel as if they’ll be with us forever. I’ve laid out countless reasons for its endurance—awards, box-office triumphs, iconic performances, cultural impact—but at its core, it really comes down to something simple: The Sound of Music makes people happy. That joy keeps audiences coming back, even as time moves forward. And while the Oscars, the records, and the craftsmanship all matter, what truly makes a film timeless isn’t getting every detail right—it’s making people feel something they never forget.