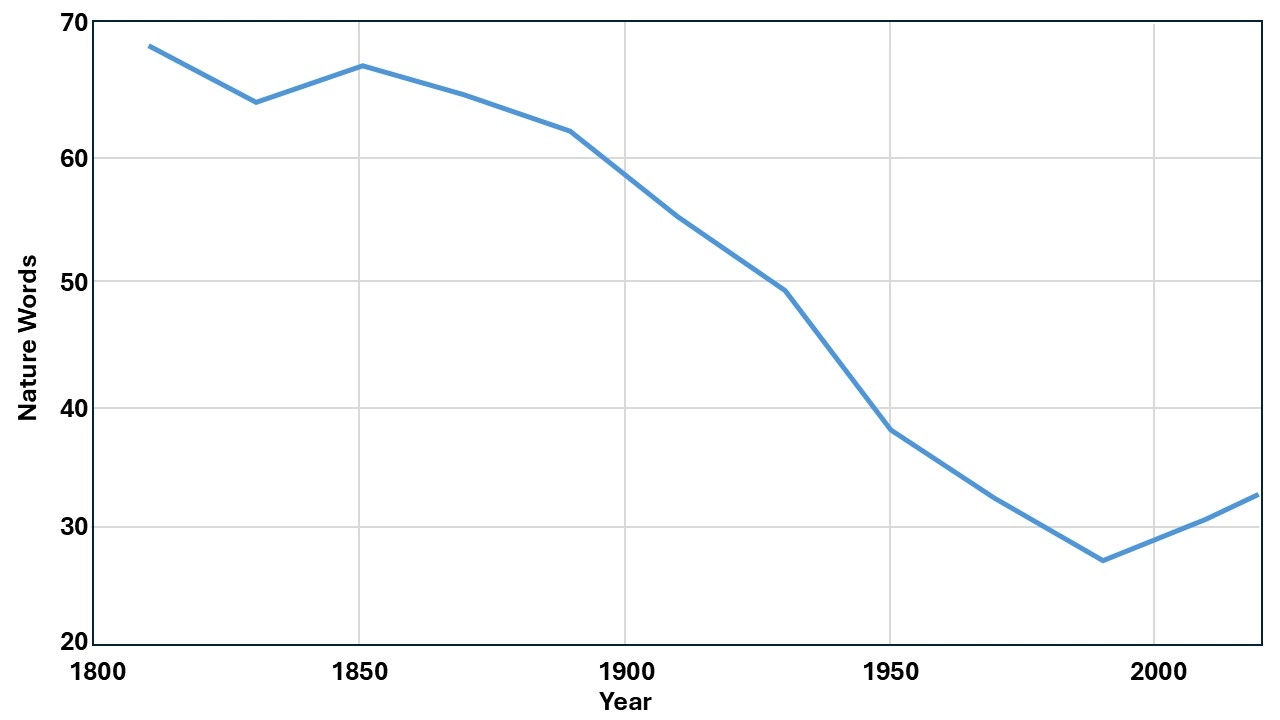

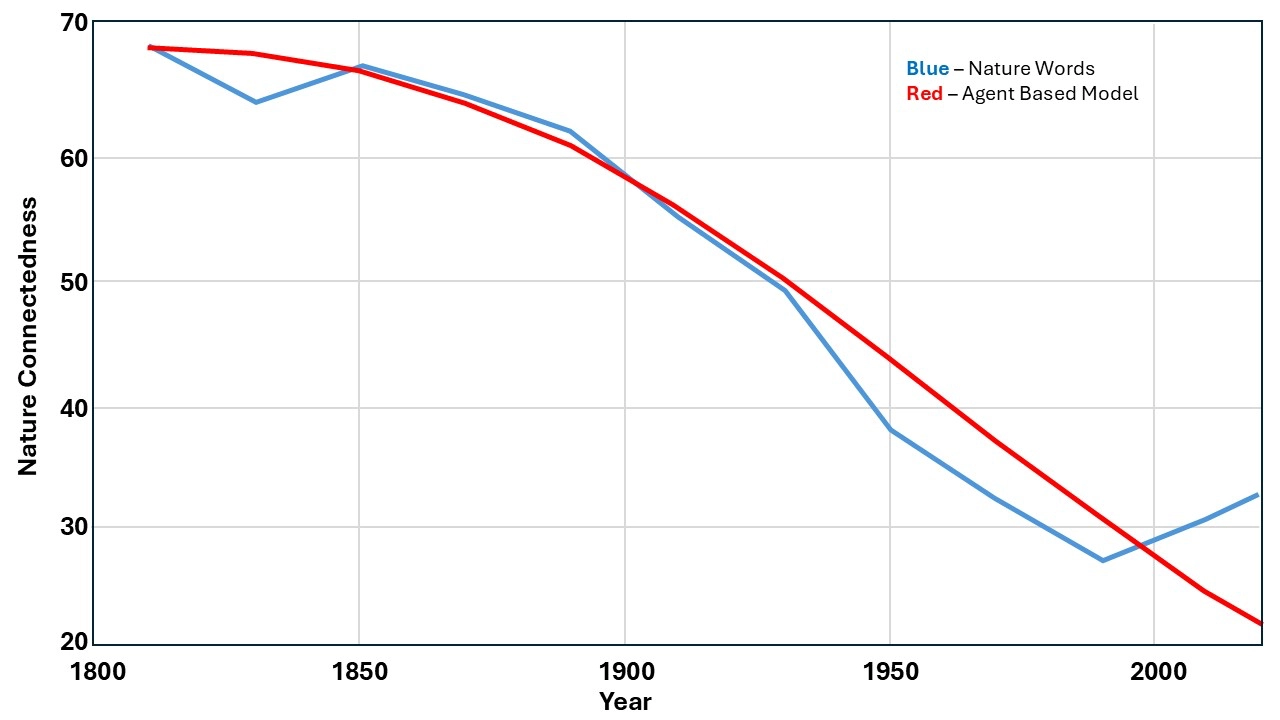

A 60% decline in nature-related words since 1800 points to a growing distance from the natural world, but it’s also a clarion call to reconnect with our surroundings.

We often take our surroundings for granted, so much so that words like “bud,” “meadow,” “bark,” “dew,” “blossom,” and the like carry little to no weight in our daily vocabulary. Granted, there aren’t many opportunities to use them, but that, in itself, is indicative of our current climate. To put it simply, we’re losing our connection to nature, and the data surrounding language and culture seem to support this. A recent study for the scientific journal Earth by Miles Richardson, professor of Human Factors and Nature Connectedness at the University of Derby, revealed that the use of nature-related words has declined significantly by 60% since the 1800s.

More specifically, Richardson tracked this decline by creating a computer model that recorded and compared simulated human–nature interactions with the use of nature-related words over time, drawing from written materials such as books. Nature connectedness went down by around 61.5% (based on a cross-sectional survey of 63 nations), while related vocabulary was at a 60.6% maximum decline in 1990. When plotted on a graph, the two models closely mirrored each other—with less than five percent error—showing a gradual yet steep decline that began accelerating around 1850, as industrialization became widespread.

READ ALSO: The Words That Told Us Everything About 2025

A Way Of Life, Passed Down And Spoken

The factors that have influenced this decline are familiar: rapid urbanization, which in turn has led to the loss of wildlife within city neighborhoods, and, just as important, the overall lack of engagement with nature, a practice that for decades was passed down from parent to child, family to family. We don’t need to be convinced with more data, because the evidence is all around us. We run around tree-lined streets, but do we really know the types of trees that surround us? The flowers and small creatures that make homes near our own?

In his study, Richardson notes that when parents already have a weak connection to nature, their children are likely to begin life with an even weaker understanding of it, and so on (what he refers to as “extinction of experience”). This helps explain why the decline has been largely continuous, marked by occasional upticks, but with little lasting recovery.

I think about my own parents, and how pleasantly surprised they are whenever I share nature-related facts with them. While they weren’t necessarily immersed in the natural world when I was growing up, they did take me to parks and animal conservation spots around my father’s university town, back when we lived in North Carolina in the early 2000s. My Korean grandmother, who spent her most formative years in a vast swath of farmland, would often take me on walks around our quaint Quezon City neighborhood whenever she’d visit, pointing to flowers and leaves, naming them in her own tongue, tending to our garden. My most treasured gift from her is a book filled with autumn leaves she picked up in a mountain, preserved with scenic landscape photos. I also remember yayas plucking bright red santan (Ixora) flowers, showing me how to taste the sweet nectar at the base of the stem after pulling out the thin thread of its slender stigma.

Still, even with this kind of exposure, my knowledge remained limited to whatever I eagerly devoured from Animal Planet and National Geographic as a child. My understanding of the local ecosystem continued to have vast gaps. It wasn’t until college, when my university offered free nature walks around campus (led by biology researchers), that things began to change.

I learned how Manila is rife with mahogany, a tree introduced in the 1900s, and how many of its species are invasive, their allelopathic effects releasing chemicals that inhibit the growth of the diverse, local vegetation. I was handed binoculars and taught how to listen for and spot the urban birds that dwell in rough tree bark and lush canopies. I learned how the survival and propagation of the tender, sweet figs that fill our mouths depend on the life cycle of wasps, the fruits serving as both birthplace and coffin.

But again, these were words and worlds I had to actively seek out, not knowledge that was handed down to me by my parents or taught in a school curriculum, and I know this isn’t a singular experience. Friends who grew up in more rural areas, provinces closer to nature, often had a far deeper understanding of local flora and fauna—but that only reinforces Richardson’s point about the effects of urbanization. I see fewer and fewer children in our neighborhood playing outdoors, pausing to look at flowers, or searching for the delightfully strange sights of bugs and animals.

Answering The Call Through Reconnection

All that said, I refuse to take a fatalistic view. If anything, the concerning drop in nature-related words and their usage should serve as inspiration—a clarion call to reconnect with the world around us. Of course, the government and other authorities must also do their part, which includes increasing green spaces in urban areas and promoting early education that encourages children to immerse themselves in the natural world.

There’s hope that people are still eager to cultivate their relationship with nature, especially as more seek digital detoxes and tranquil breaks from fast-paced city life. Last year, I wrote a piece about common birds in Manila neighborhoods, which received a warm response—a sign that Filipinos crave accessible resources to engage with these topics.

This explains why Filipina environmentalist Celine Murillo has built a strong following on social media, where she shares facts about local wildlife and plants, giving names to things many of us may never have learned to name. Even local ingredients, born from the land, are integral parts of this education: projects like Lokalpedia are creating crucial archives of biocultural assets (particularly edible species of flora, fauna, and fungi) for people to explore and reference. It’s a global movement as well, with social media accounts like Odd Animal Specimens and @goldenstatenaturalist following suit.

You don’t have to be a “tree-hugger” to appreciate the world we live in. To truly know the food you put in your mouth, the grass your feet walk on, the trees that give you shade, and the birdsong that cuts through the harshness of car horns is as essential as remembering your own name. Life has, with no exaggeration, grown richer since I started learning more about the words that constitute it; in small ways, yes, but in ways that matter. Let’s stop to smell the roses—and if we can recognize and understand them more intimately, all the better.