Jolly old Saint Nick has long been a Christmas figurehead across cultures, but where did the image of the cookie-eating, fireplace-hopping, red-clad bearded man truly come from?

Santa Claus is a figure so mythic, so seemingly antiquated, that no one really stops to question his origins. It feels like he’s always been around—riding a sleigh pulled by flying reindeer, munching on a plate of cookies, bearing gifts by the sackful, and doling out coal to the year’s naughtiest. But think about it for a moment: this is hilariously specific imagery. Where did it even come from? Like any legend, he’s an amalgamation of good old marketing, a bit of Hollywood magic, human hopes and needs, and real-life histories that got caught in the mix. So who exactly is the man we’ve given so many names to, from Kris Cringle to Saint Nick? We break it down just in time for the Christmas season.

READ ALSO: Merry Christmas, Filipinos! It’s September.

In The Beginning, There Was Saint Nicholas

You’ve probably heard about this from that one friend who pushes up their glasses and says, “Well, actually, Santa Claus is based on Saint Nicholas…” before trailing off to talk about a bishop who died centuries ago, but let’s run through it again anyways.

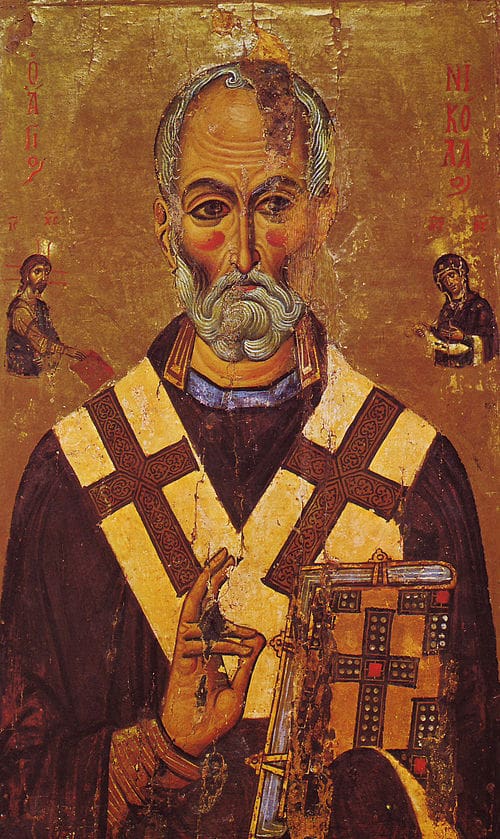

Saint Nicholas was the real-life figure who inspired the myth of Santa, an early Christian bishop born circa 280 A.D. in Myra, a place near what’s now known as Turkey. And like most figures who are recognized as saints, he devoted much of his life to serving the marginalized, his compassion known throughout the communities he served. Eventually, he came to be the protector of children and sailors, and was celebrated throughout Europe even after the Protestant Reformation that discouraged the veneration of saints.

During the late 1700s, Dutch immigrants in the United States—more specifically New York—would pay tribute to the saint during the anniversary of his death, which is December 6. His name, “Santa Claus,” is actually derived from his Dutch name, “Sint Nikolaas,” shortened to “Sinter Klaas.”

Yet it wasn’t until writers and artists began sharing their own tales and visual renditions of the saint that his presence transformed into something entirely different, a version of Saint Nicholas much closer to the one we know today.

Hurry Down The Chimney Tonight

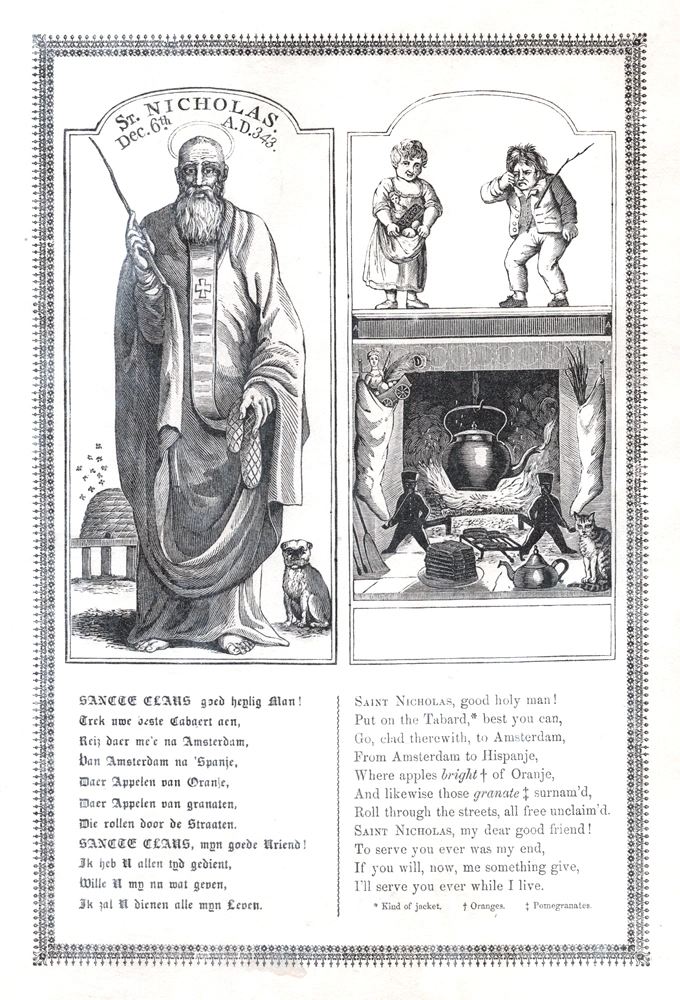

The first American image of Santa Claus—we’re using the country as a basis, since its image of the man became the most popular—happened to be an illustration by Alexander Anderson, who was commissioned by John Pintard of the New York Historical Society. Pintard requested woodcut pictures that he could distribute during the society’s St. Nicholas Festival dinner (held on December 6), the first of what would become an annual tradition that began as a way for the Americans to distinguish themselves from the English after the Revolutionary War (the latter would later develop their own myth of Father Christmas).

These illustrations featured imagery that’s still associated with Santa Claus today, namely, sweet treats by the fireplace and filled stockings. This was also the first time that his way of distinguishing “naughty” and “nice” children was introduced. The picture shows one stocking stuffed with toys, meant for the happy and obedient girl in the illustration, and another stocking filled with birch rod for her incorrigible brother (who’s very clearly upset). Coal would replace the birch rod later on, which might’ve stemmed from the landscape of the industrial revolution (who wants more coal when you’re constantly surrounded by soot and smoke?).

As it happens, writer Washington Irving would be accepted into the society, and, witnessing the feast, decided to create his own accounts of Saint Nicholas through the perspective of the Dutch immigrants. The stories stuck, making their way outside the society and into the wider culture.

By 1821, an illustrated poem titled “Old Santeclaus with Much Delight” by Clement Clarke Moore would introduce Santa’s reindeer and sleigh, as well as the idea that he visits homes on Christmas Eve, rather than St. Nicholas’ Day. “Old Santeclaus with much delight/His reindeer drives this frosty night,/O’er chimney-tops, and tracks of snow,/To bring his yearly gifts to you,” he writes. The poem would also touch upon the naughty and nice treatment, cementing the concept of the birch rod as a gift for disobedient kids.

Two years later in 1823, Moore would also write the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (though most people remember it by its first line, “‘Twas the night before Christmas…”), which gave his reindeers their famous names (Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donder, Blitzen), and Santa his distinctive characteristics: rosy red cheeks, a red nose, a white fluffy beard, and yes, his rotund stature (He had a broad face and a little round belly./That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly./He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf…).

Many of us might’ve encountered this poem in some form, either through cartoons or storybooks, but I doubt we ever knew just how influential and pioneering its depictions of Santa Claus were.

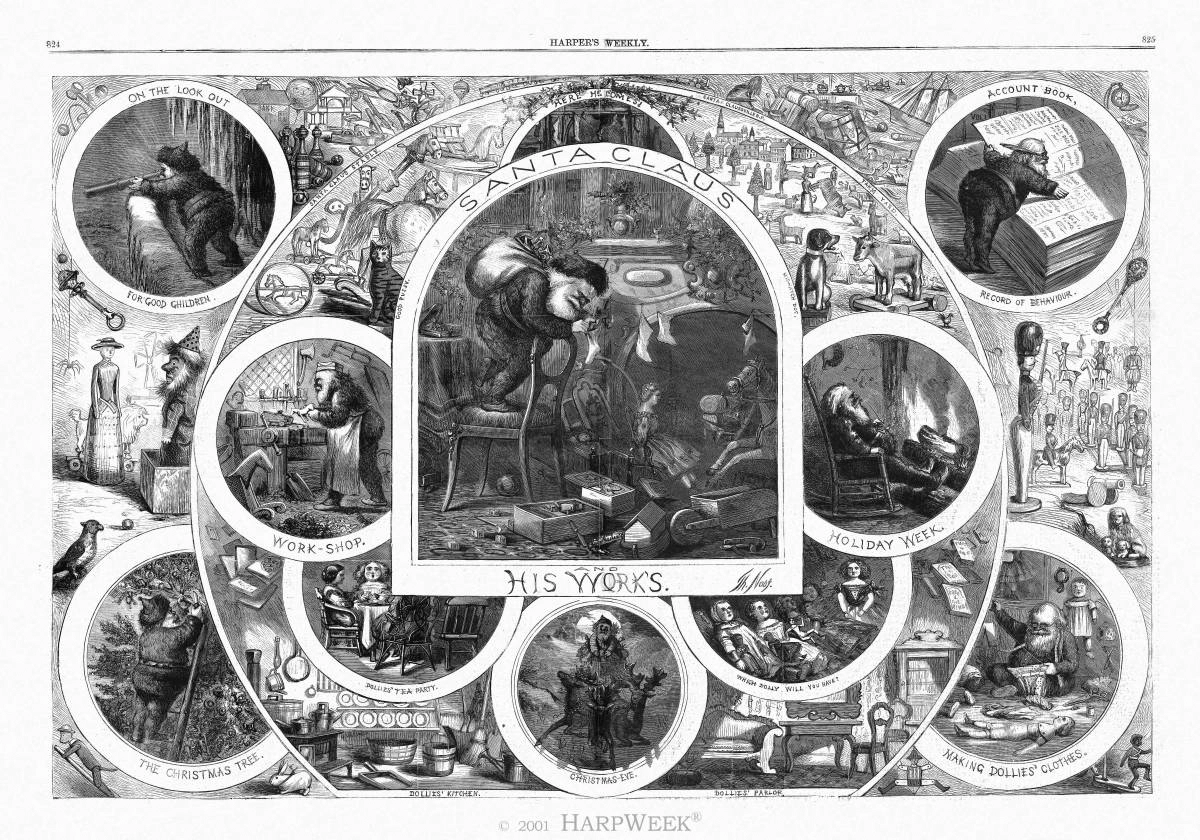

While Moore popularized the most iconic version of St. Nicholas through the written word, it was caricaturist and editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast who shaped the visual Santa Claus we recognize now, including his workshop filled with elves. He’s widely known today as the man who created the donkey and elephant imagery for Democrats and Republicans, respectively, so it’s no surprise that politics lies at the center of this myth-making.

Nast had illustrated Santa Claus, based heavily on Moore’s work, to aid in propaganda for the Union cause during the American Civil War. His drawings would appear in the political magazine Harper’s Weekly until 1866—by then, Nast had created 33 pictures that held deeper symbolic meanings connecting to the state of politics at the time. Whether or not people understood these allusions wasn’t the point: the progenitor of the modern Santa, in all his holly jolly glory, was born.

So yes, contrary to what you might’ve heard, it wasn’t Coca-Cola that invented the modern Santa Claus, though they certainly played a huge part in cementing his status in our shared Christmas culture, using him as the face of their holiday campaigns through memorable illustrations by Haddon Sundblom.

The Modern Santa Claus

It would be a great task to illustrate the entire history and evolution of Santa Claus. He’s undergone countless iterations over the years, all of which are reflections of their zeitgeists. It’s a holiday multiverse that would give Marvel and DC a run for their money, so much so that even side characters affiliated with him have entire lore of their own.

Take Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer, who was never included in Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” He came into being when Robert L. May—a copywriter at the Montgomery Ward department store—was tasked with creating a Christmas storybook for customers as a promotional stunt in 1939.

For the most part, that picture of a round, laughing, red-cheeked bearded man has stayed with us through various forms of media, especially books, holiday cards, and films. Yet every creative will add their own twists to the grand Santa canon. For instance, 1994’s The Santa Clause (probably the cleverest festive movie title you’ll find) told the world that there have been multiple people taking on the role of Santa via legal agreement—complete with a magical, physical transformation.

Though, what I personally find most interesting (and hilarious), is this fairly recent shift towards a badass, tough, and yes at times, ruggedly hot (depending on who you ask) Santa that veers far away from that grandfatherly man we’re all familiar with. I’m not talking about 2003’s Bad Santa, in which a criminal uses his job as a mall Santa to commit robberies, but rather, films that show the real guy all buffed up.

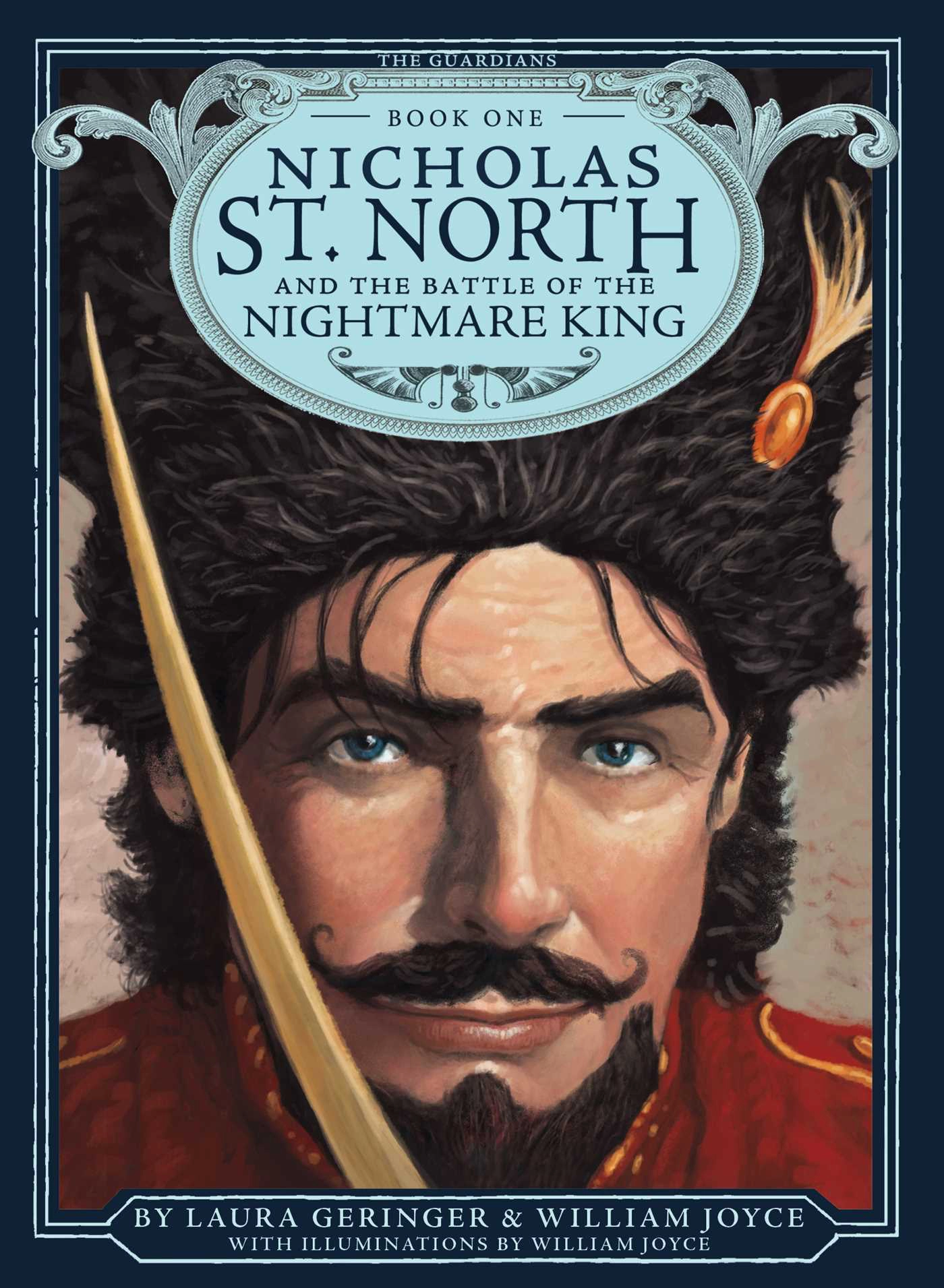

Dreamworks’ Rise of the Guardians (based on the beloved The Guardians book series of William Joyce) presented Santa as a muscular Russian warrior also called “Nicholas St. North.” And yes, excruciatingly, he’s an even younger hunk in Joyce’s illustrations! And just when you think broad Santa was going to stop there, 2019’s beautifully animated Klaus has him looking more like a majestic, towering carpenter of a man than someone whose diet mainly consists of chocolate chip cookies.

My personal theory of why this image has become more common is simply because people are searching for a man who reflects the grittier, more modern sensibilities we have today. It’s not that the classic Santa Claus is dead, but I suppose people are looking for someone who feels more “real.” Or maybe it’s not that deep, and people are just all too happy to make Santa Claus sexy the way Guillermo del Toro loves making his monsters love interests. I mean, I guess that in itself is a realistic depiction: carrying sacks of toys and driving a sleigh would give anyone some biceps.

And yes, it’s kind of ridiculous, but we love it anyway. This just proves that myths are, ultimately, fueled by the eccentricities, desires, and creativity of the human mind. Santa’s been a saint, a jolly grandpa, a wartime icon, and now a shredded fantasy lumberjack. But that’s the beauty of it: he’s whatever each generation needs him to be. And if that means he’s due for another reinvention in a decade or two, well, he’s handled stranger arcs.