From pioneers to rising voices, Filipino artists are reimagining textiles as powerful vessels of memory, identity, and resistance—blurring the line between craft and contemporary art.

Textiles have always been with us— wrapped around bodies, draped over windows, and tucked into drawers. Yet for much of history, they’ve been dismissed as too soft, too ordinary, too “crafty” to be considered high art. Across cultures and centuries, textiles have been entwined with ideas of femininity and domesticity. In the Philippines, textile production was once the exclusive domain of women, with handwoven cloths serving not merely as clothing or decor but as ceremonial markers.

However, colonial influence and the rise of Western art hierarchies created a split: painting and sculpture were elevated as fine art, while embroidery and weaving were relegated to the realm of “craft .” As a result, much of women’s artistic contributions were devalued and quietly tucked out of sight. Even today, traces of this distinction persist. Works that engage with thread and cloth often still carry the connotations of “textile”—domestic, decorative, and secondary—even when they are, in fact, powerful acts of art.

Still, artists have continually pushed against these boundaries. Today, many contemporary Filipino artists find the old divisions between “art” and “craft ” less relevant. What matters now is intention: how materials are used, what they carry, and whom they speak for. Techniques once confined to the domestic—tatting, embroidery, wrapping, quilting—are being reframed as central modes of storytelling.

What’s striking about this growing movement is how often textile work carries the echoes of those who came before— mothers, grandmothers, seamstresses, and weavers, many of whom sewed out of necessity rather than choice. Thread by thread, these artists reshape inherited materials into contemporary expressions of care, resistance, and identity, expanding the definition of art itself.

READ ALSO: Woven Consciousness: The Role Of Artisans In Slow Fashion

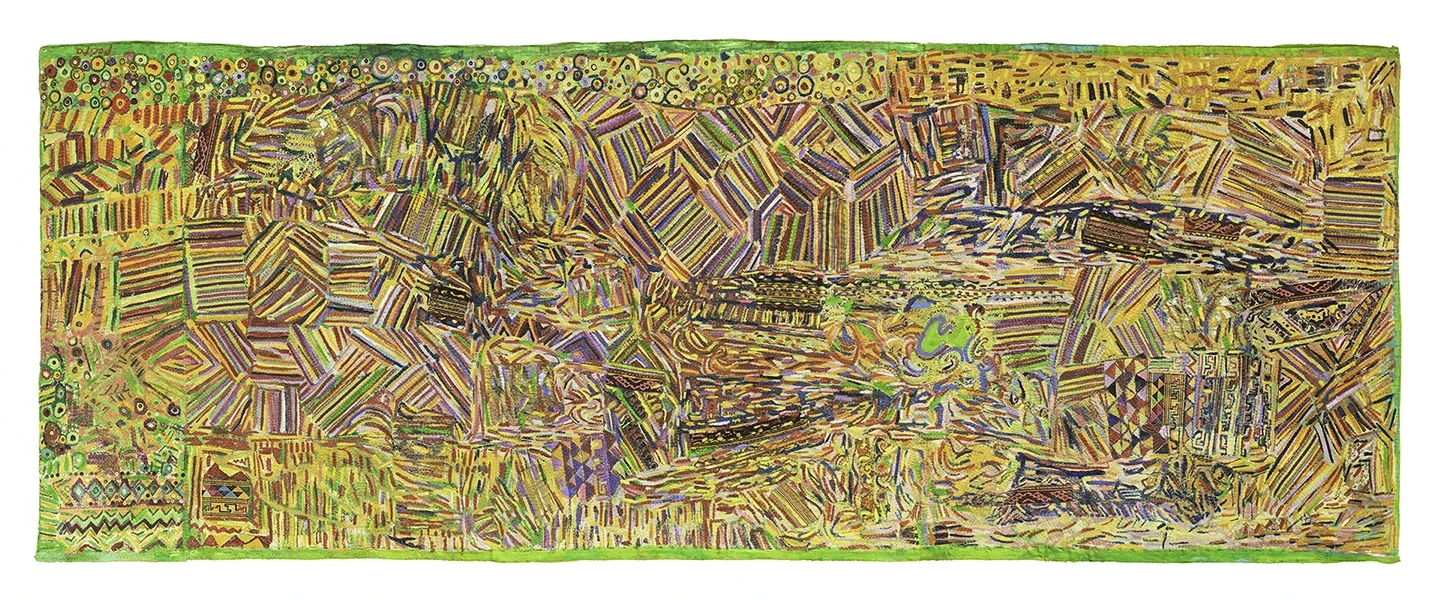

PACITA ABAD

One of the earliest and most recognizable figures to popularize textile art in contemporary Southeast Asia was Pacita Abad. Born in Basco, Batanes, her journey as an artist was shaped by experiences across continents. After leaving the Philippines in the 1970s, she traveled extensively throughout Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas, absorbing diverse cultural influences.

Known for her large-scale trapunto paintings (quilted, painted, and embroidered works), Abad embraced fabric as both a medium and a message. Her travels introduced her to textile traditions from around the world, which she incorporated alongside indigenous Filipino techniques.

“The sky is the limit” (2000) by Pacita Abad/Photo courtesy of Silverlens (Manila/New York) and the Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Recently, at Art Basel Hong Kong 2025, “The Sky is the Limit” (1996–2000) took centre stage in the Encounters sector. This dedicated platform within Art Basel showcases large-scale sculptures and installations that transcend the traditional art fair booth format, allowing visitors to experience immersive works that might otherwise be impossible to display in conventional gallery spaces. Curated specifically to create dialogue between monumental artworks and the public, Encounters represents some of the most ambitious artistic presentations at the fair.

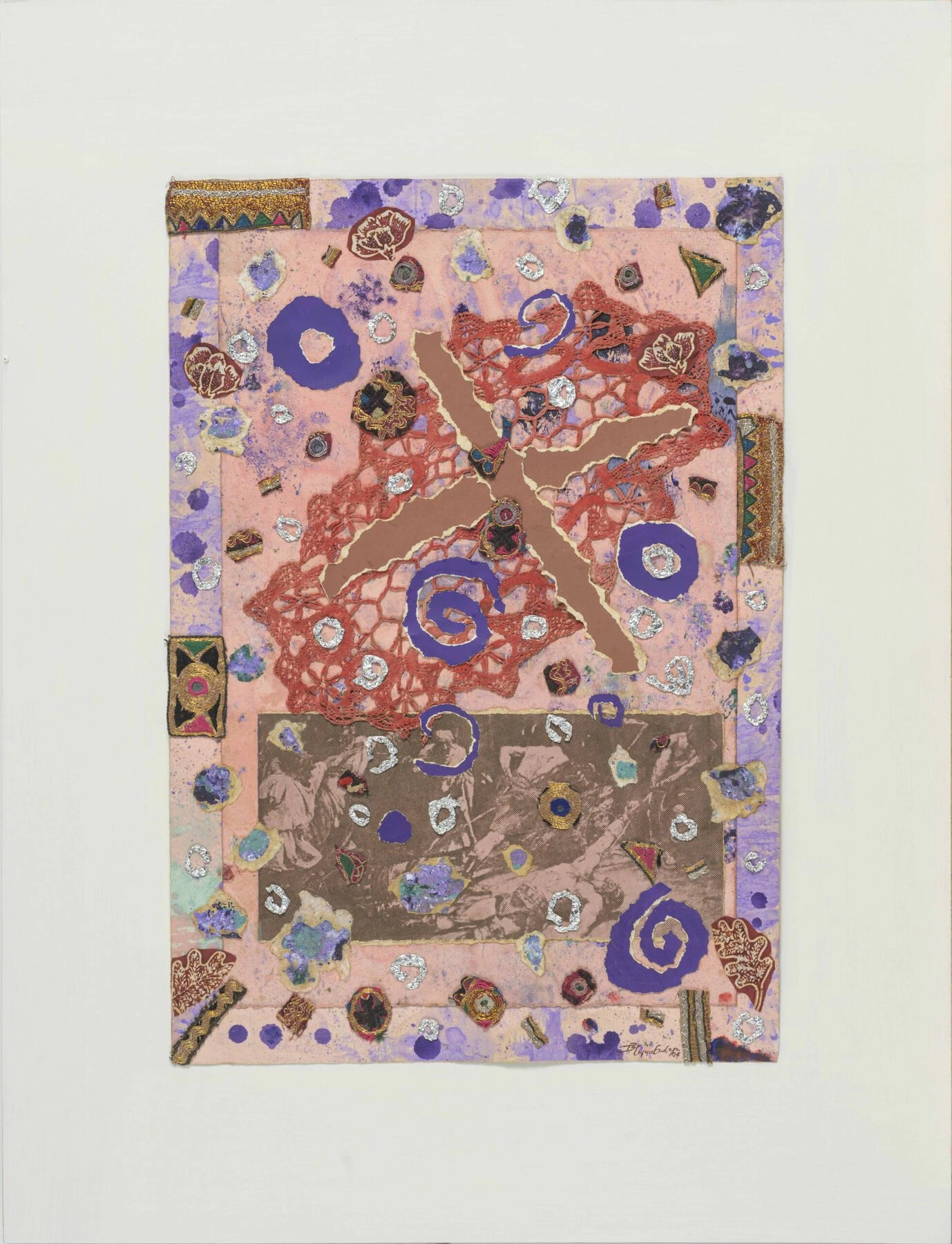

IMELDA CAJIPE ENDAYA

Imelda Cajipe Endaya is one of the pioneering Filipino artists who began experimenting with textile in her works during the 1970s. Before this pivotal shift, she was already an established printmaker and painter. Faced with rising material costs, she turned to crochet works and fabrics handed down by her female relatives, describing them as “mementos of nurturing by women in her family and the culture they passed down to her.”

In the late 1970s, Cajipe Endaya began incorporating found and domestic materials into her mixed media works. “Bintana ni Momoy” (1983) is a key example, layering a denim jacket, checkered fabric, and sawali and nipa materials taken directly from her home. In other pieces, she uses household objects like old curtains salvaged from everyday life. Her experimental use of textile helped shape the practices of later artists, including Marina Cruz, who similarly explores fabric as a medium for personal and historical storytelling.

MARINA CRUZ

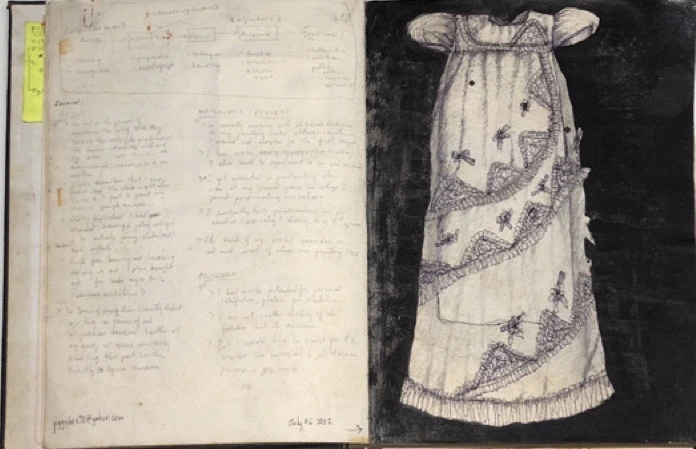

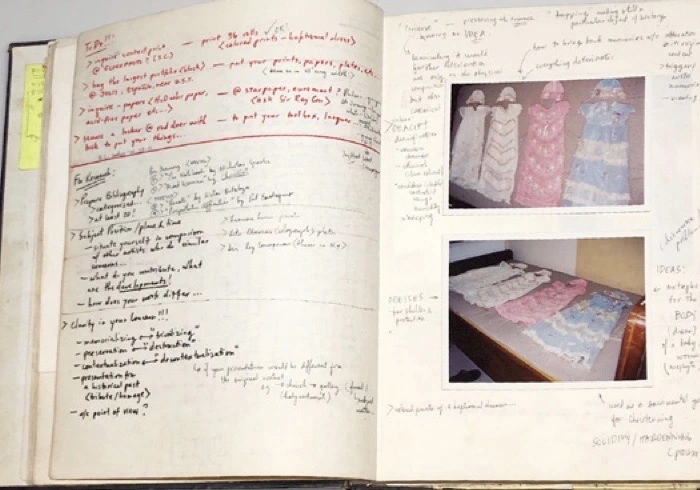

Marina Cruz’s work often evokes nostalgia and reflects on family histories. She is best known for her photorealistic paintings of baby dresses, capturing not just the shape of each garment but also the textures, folds, and stitching that give it character. Many of the dresses were sewn by her grandmother for her mother and aunt, twins named Laura and Luisa, and have become vessels of memory and emotion in Cruz’s practice.

“When I was in high school I would stare at our curtains, looking at the shapes, patterns, and the textures of the cloth. When I was doing my thesis, I was looking for something that would give me that kind of texture—a grid/weave texture,” Cruz recalls. “I looked through my grandmother’s old cabinets and was amazed when I saw the baptismal dresses. I thought, wow, I should make something different. I shifted to objectifying memory.

In “Laura II” (2008), Cruz prints a photograph of a fragile, timeworn dress and embroiders it with symbolic details: two flowers for the twins, three blooms for Laura’s daughters, a fallen petal for a miscarriage, and a bird representing a daughter who has moved abroad. Other embroidered elements, such as the irregular roof of their home and the family dog, mark the dress as both garment and map. Through these delicate surfaces, Cruz transforms clothing into quiet portraits of absence and presence.

“I want to present [textiles] in their present stage and appreciate that even if it is worn or torn with all its imperfections, it can be beautiful like a person who aged, with more character, more wisdom,” Cruz reflects. “I learned to appreciate the vulnerabilities, in the same way that you know a person.”

RAFFY NAPAY

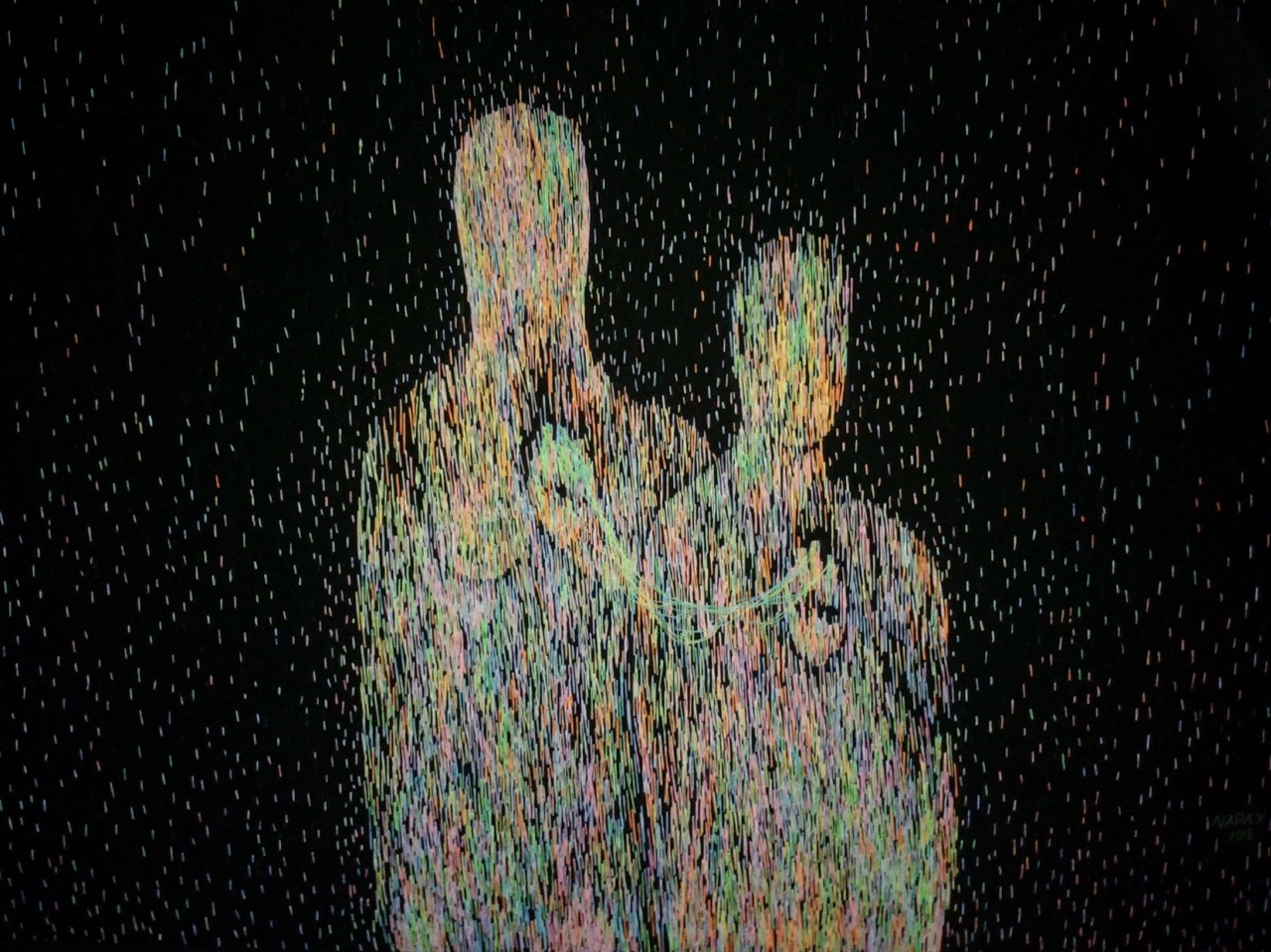

A similar thread of maternal influence runs through the work of Raffy Napay, one of the relatively few male artists in the Philippines who personally hand-embroiders his pieces. Napay turned to thread after developing an allergy to oil paints, embracing a material that had been part of his everyday life, raised by his mother who worked as a seamstress. Conscious of the inspiration he draws from her and the broader traditions of feminine labor, Napay uses thread to hold memory and emotion in densely layered, tactile surfaces.

“The machine was in the house—I’ve seen that since we were kids, she was sewing, I’d go to shops with her. She taught me everything—how to pace, how to not break thread. She used to sew my clothes,” Napay reflects. “But my mom would criticize me—I prefer the imperfect, the loose threads and stuff, not like usual people who sew. This is the difference between painters and sewers.”

“When sewing, I also feel more connected to my mother’s life,” he adds. One of his most beloved pieces, “Family Tricycle” (2003), pays tribute to his parents: his mother’s sewing helped support the family, and the proceeds from the painting allowed them to purchase the tricycle his father would drive.

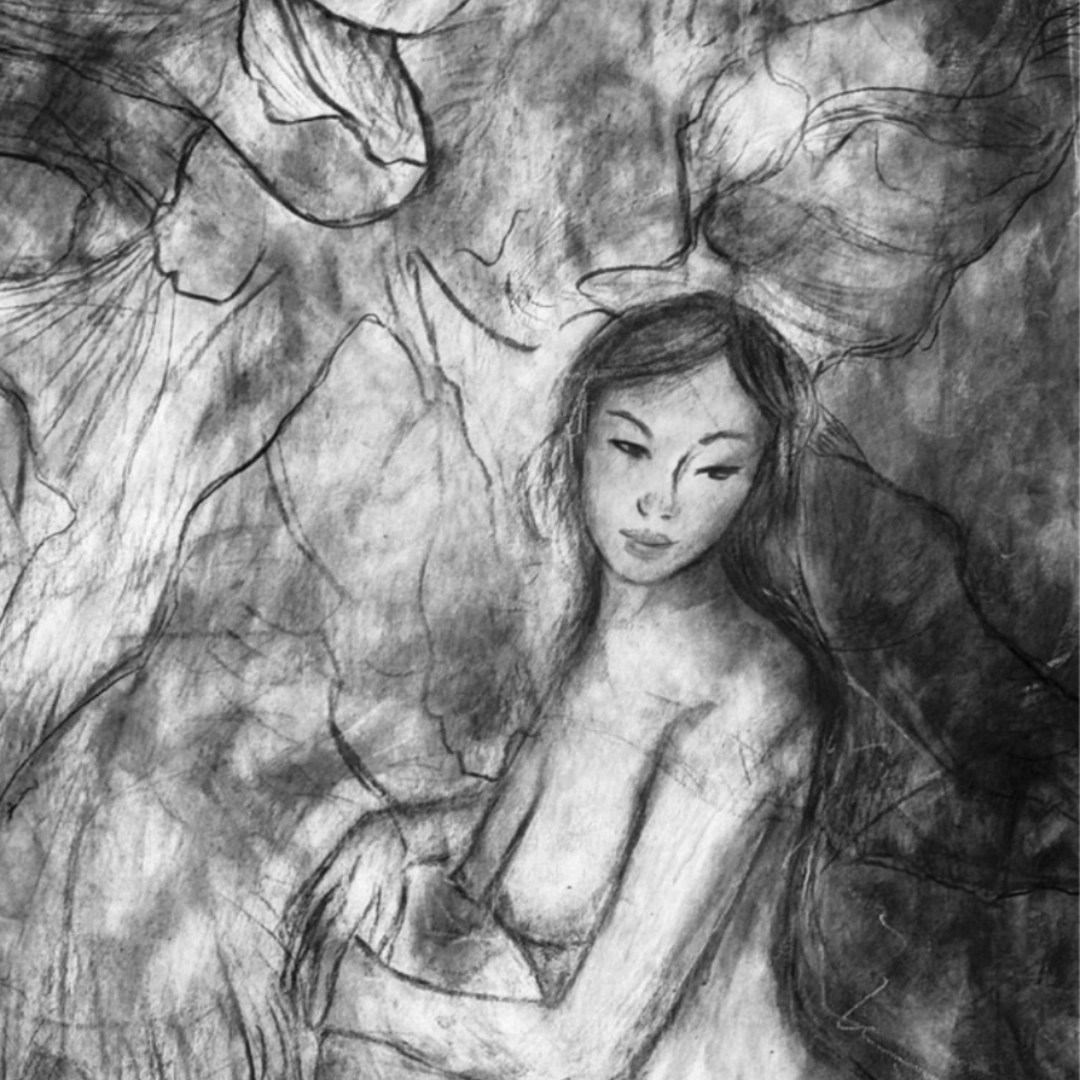

GERALDINE JAVIER

For Geraldine Javier, textile is woven into both her process and her environment. Since relocating her studio to Cuenca, Batangas, Javier has collaborated closely with her local community, training neighbors as studio assistants and ensuring that the proceeds from her works go directly toward supporting their livelihoods. Many of her pieces feature hand-tatted lace, a time-intensive form of knotted needlework, which she incorporates into mixed media paintings and sculptural installations.

Javier attributes her early interest in textiles and crafts to her mother, a Home Economics teacher, whose influence continues to shape her practice. These intricate, laborious details honor traditional domestic skills and challenge the speed and scale of contemporary production, inviting slower and more mindful forms of making.

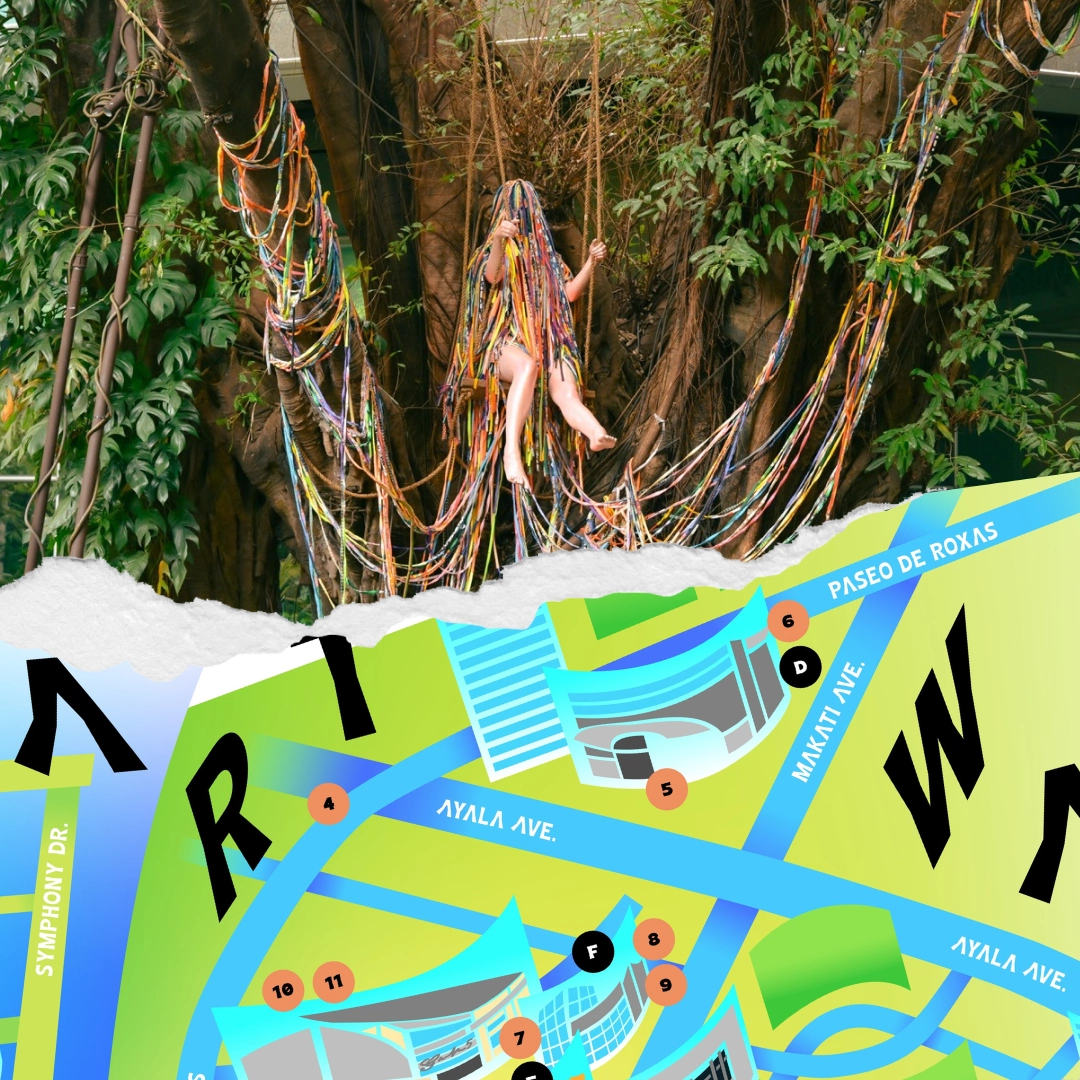

WINNA GO

Building on her earlier Puzzled Identity series, Chinese-Filipino artist Winna Go’s latest body of work positions painting as an act of weaving. In Latitudes of Being and Belonging (2025), she turns to textiles as both subject and symbol, not through fabric itself, but through paint. Presented at Art Fair Philippines 2025, the exhibition features large-scale oil-on-canvas works that trace the complex textures of woven patterns and embroidery, drawing from Filipino and Chinese traditions.

“Prior to painting, I would do extensive research on existing Chinese and Filipino textiles. I would usually go around and look for fabrics that I can draw inspiration from. I also rely on online archives,” Go explains of her artistic process. “Afterwards, I would juxtapose the fabric and play around with it in order to find the proper balance between colors, details, subject matter, and composition. Once satisfied, I then translate this onto canvas.”

Each vast canvas is fractured into a grid of squares, evoking a puzzle, an ordered framework that mirrors the layered, sometimes dissonant experience of cultural identity. Through these richly textured surfaces, Go continues her exploration of what it means to belong somewhere between cultures, languages, and generations, presenting identity not as a fixed point but as an ever-evolving tapestry.

CELLINE MERCADO

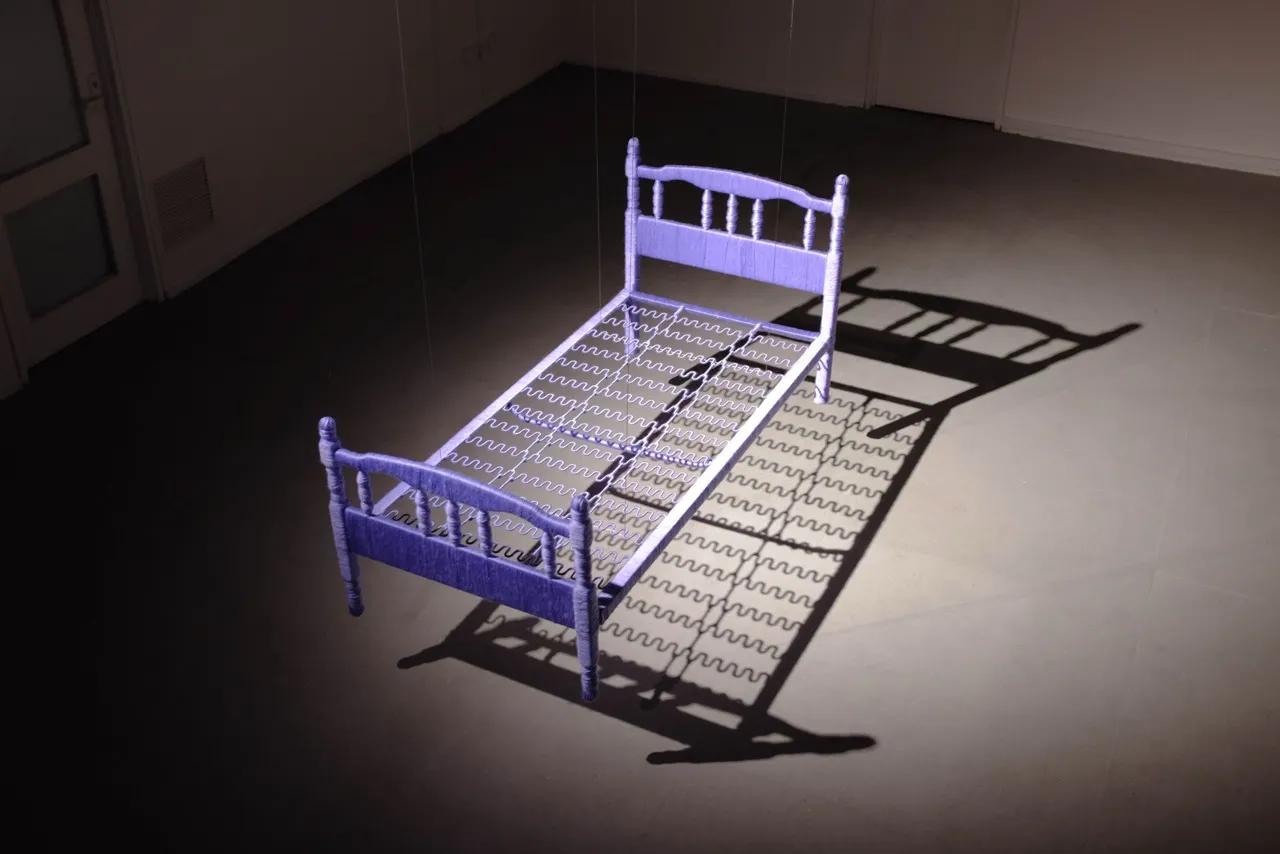

In Celline Mercado’s sculptural installations, thread takes on a more ambiguous role—both protective and confining. In Breathing Room (2024), pastel-coloured dorm furniture—a bed frame, a desk, a swivel chair—is suspended and tightly wrapped in yarn. At first glance, the softness and color palette invite warmth. But the obsessive wrapping and functionless suspension point toward psychological tension and displacement.

Born in San Fernando, Pampanga, now based in Melbourne, Australia, Mercado’s ongoing series Between the Lines (2022-present) explores her experience as a migrant navigating identity, colonial history, and cultural loss.

“The colonial overtone is implicit in my installations. It does not ever announce itself. Perhaps this serves to capture colonial mentality’s complex, systemic embedment into the Filipino psyche,” says Mercado in her artist’s statement. “After centuries, it has become invisible but remains ever present, weaving itself into the very reasons why we choose or are forced to leave.”

“Predominantly, Filipinos leave with the hopes of landing in better circumstances,” she continues. “I myself made this decision in coming to Australia. But the utopia is that I never had to leave, that to be Filipino in the Philippines was enough. This search for a soft place to land might never end, but if it does, perhaps my lamps, chairs, and beds will finally touch the ground.”

Soft wool encases hard furniture, while the process of wrapping becomes both ritual and labor—meditative yet exhausting. Her installations exist in a state of limbo, much like the diasporic self: not fully here, nor entirely there.

This article originally appeared in our June 2025 issue.