Through their food writing, Doreen Fernandez and Edilberto Alegre taught Filipino readers to better understand the nation on their plates; decades later, their works continue to nourish.

I first encountered the work of Doreen Fernandez in a specialized English class during my freshman year of college; it was a part of our syllabus, meant to be one essay out of several in a term. But, as it is with many people who read her work, the experience left more of an indelible mark than I anticipated. With its unassuming title, “Balut to Barbeque: Philippine Street Food,” I had wrongly thought it would be a plain rundown of the usual fare served by vendors sprinkled along every corner of Manila. What I found instead was the pulsing heart of a country—or at least one part of it—rendered in black text and offered up like a gift.

Fernandez isn’t just enumerating beloved staples like balut, “dirty” ice cream, taho, and banana-cue. She refuses to simply list flavors or ingredients, opting to evoke collective memory by tying our cuisine to presentation, process, people, place, history, and even linguistics. In her hands, food becomes poetry, the accessibility and elegance of her language a doorway to the things we enjoy yet often take for granted.

The writer’s exploration of street food transforms it into something more than the fulfillment of a need or the result of a lack of resources: it’s made up of, as she describes, “meals as movable as time” and “flexible feasts that make their own space, and shape their own meaning,” whether that’s in a school, churchyard, central business district, or transportation center.

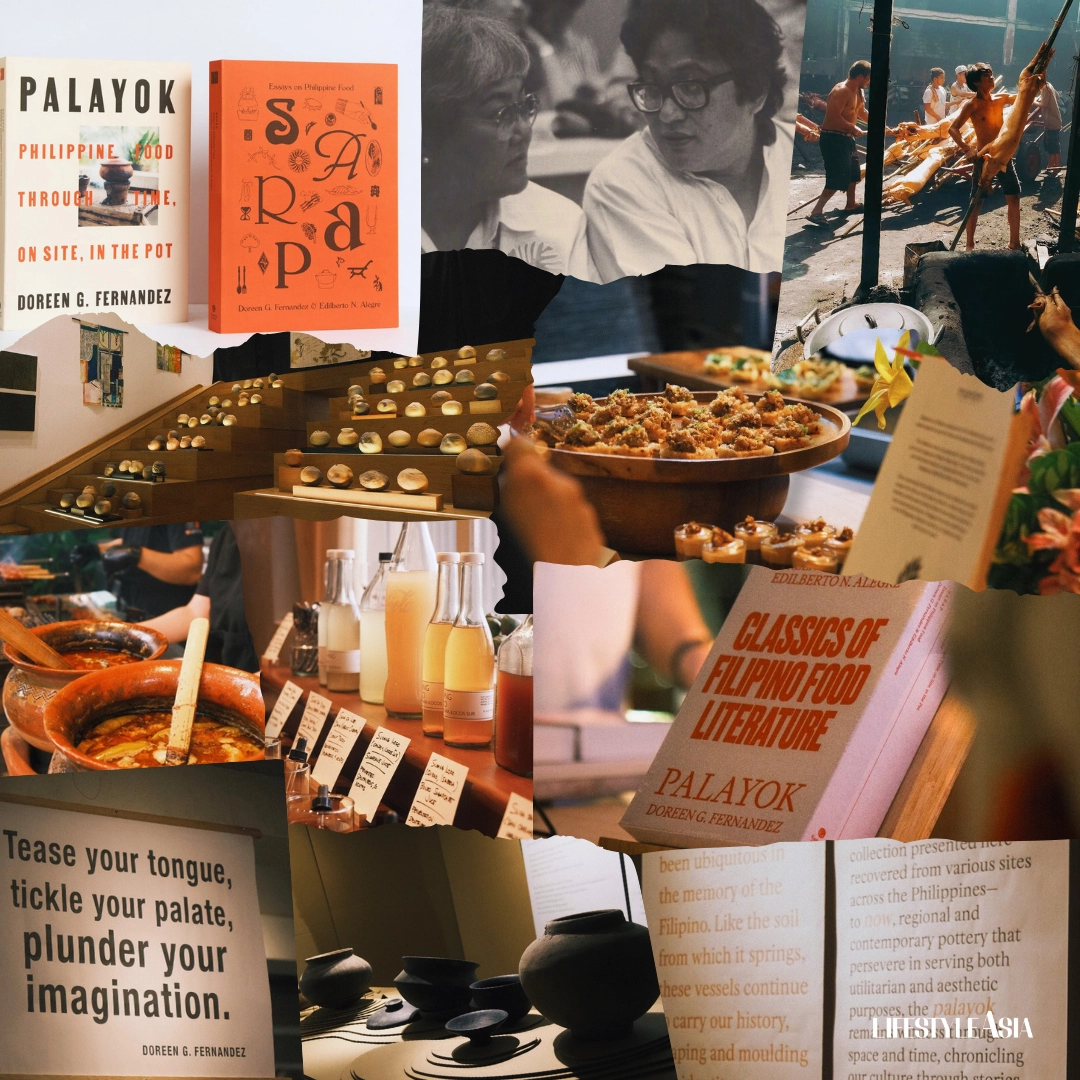

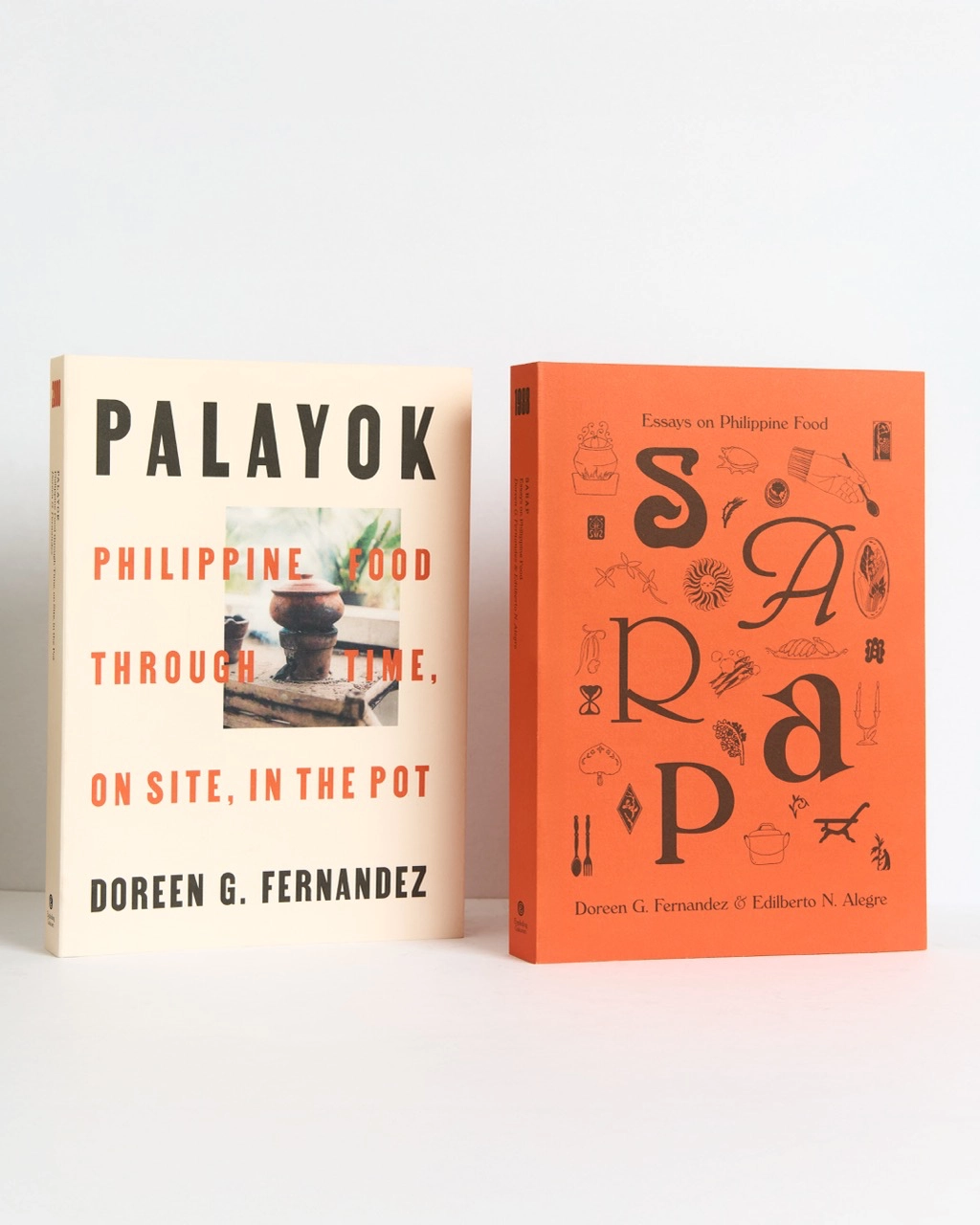

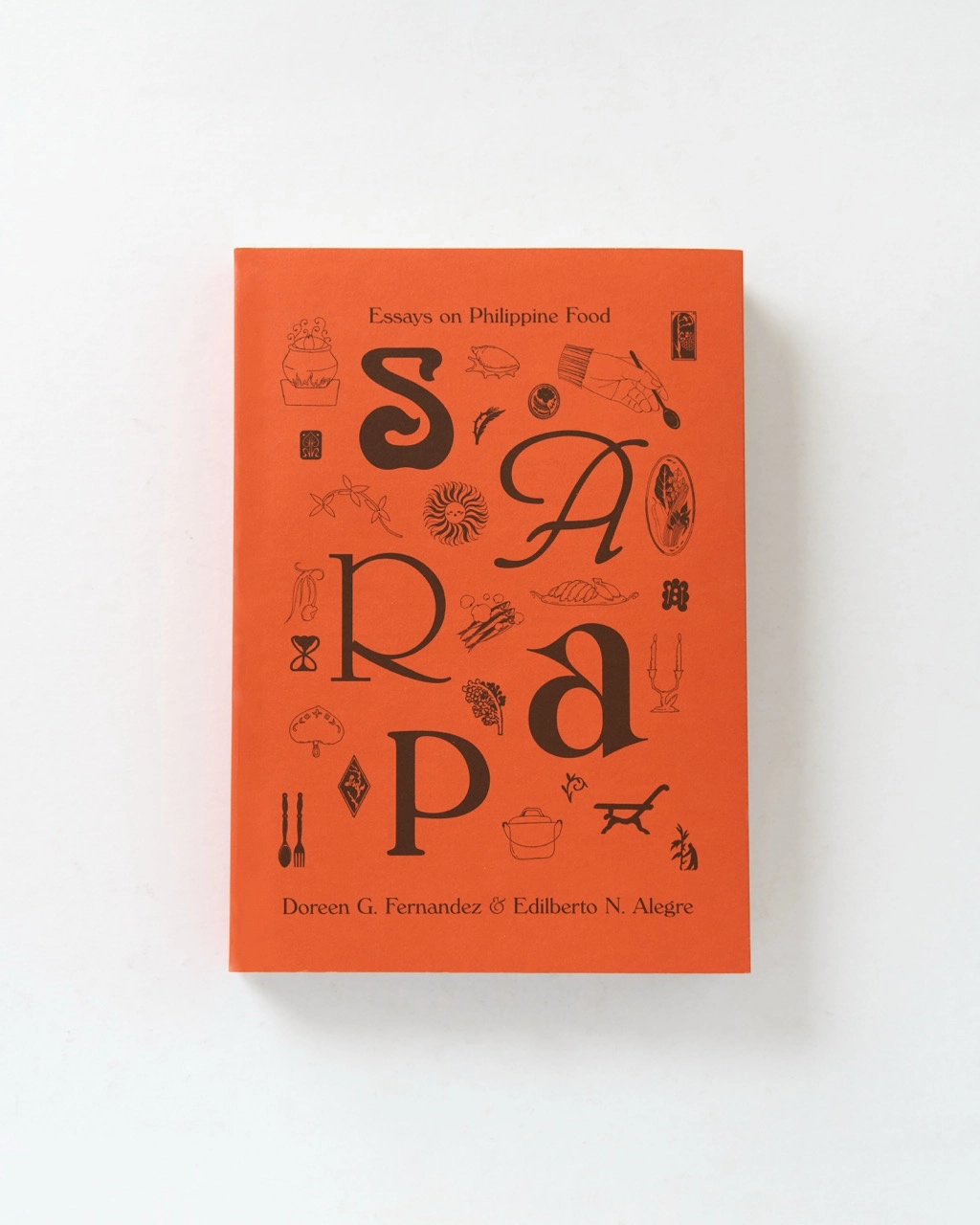

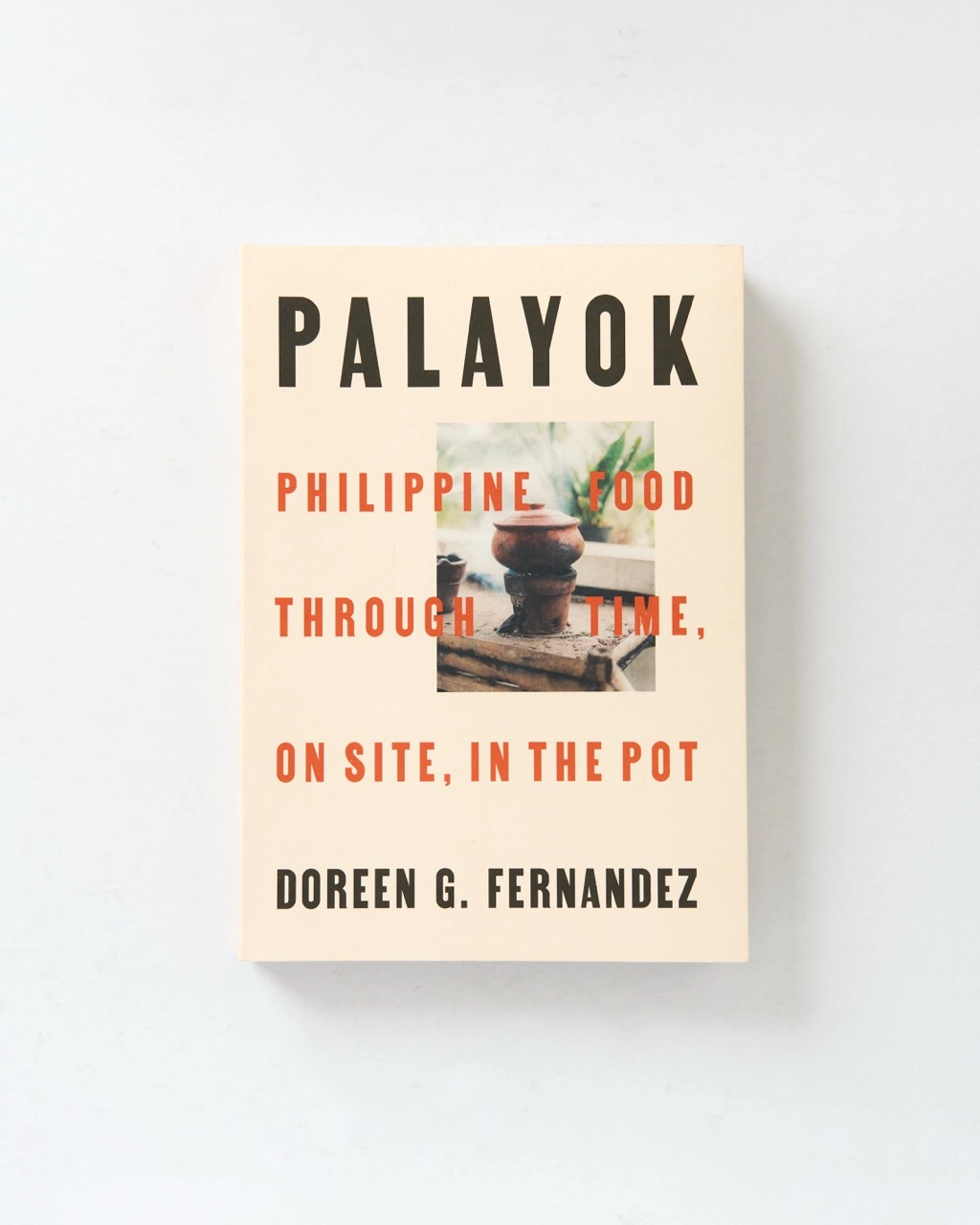

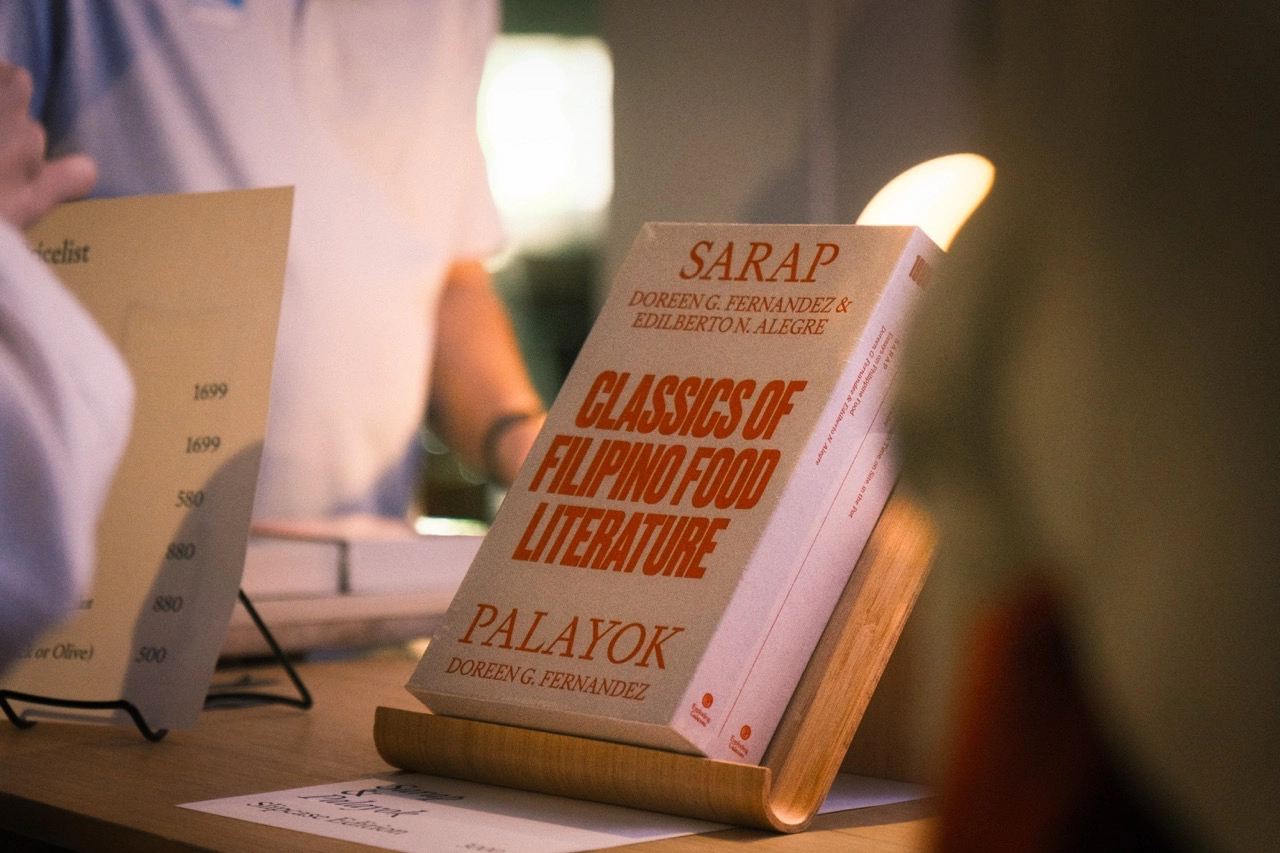

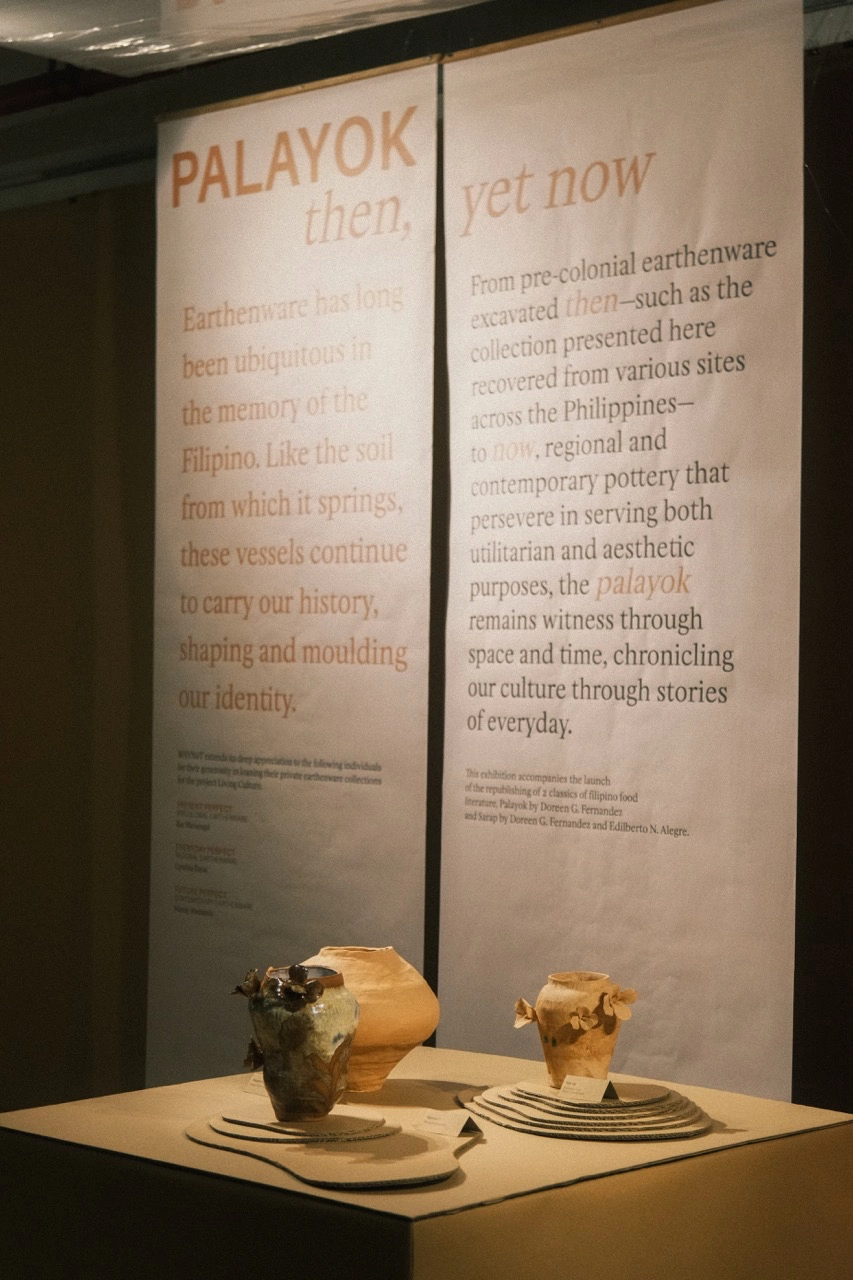

This only skims the surface of the writer’s body of work—which, alongside the equally brilliant essays of her longtime collaborator and fellow scholar Edilberto Alegre, has gotten a new lease on life. Homegrown publisher Exploding Galaxies recently reissued stunning editions of the writers’ 1988 collection Sarap: Essays on Philippine Food, and Fernandez’s 2000 book Palayok: Philippine Food Through Time, On Site, In the Pot—one of her final works before passing in 2002.

While Fernandez and Alegre are no longer with us, their words remain, and time has only deepened their significance. This is especially true in today’s landscape, where Filipino food is being appreciated and championed both locally—thanks to a flourishing F&B industry—and globally as part of a larger rediscovery of identity and heritage. Their essays remind us why these flavors matter in the first place, and how even the simplest dishes are part of a much greater story of who we are.

READ ALSO: Exploding Galaxies Republishes Filipino Food Essay Collections “Sarap” And “Palayok”

Exploding Galaxies Republishes Two Classics

Exploding Galaxies began with the goal of rediscovering and sharing the “lost classics” of Philippine literature. Its primary focus were initially works of fiction, as its founder Mara Coson explains in an interview with Lifestyle Asia. However, there was a clear and resounding demand for Fernandez’s non-fiction from readers both new and old—a testament to the devoted following she garnered over the years. Exploding Galaxies’ reissue marks the first time both Sarap and Palayok have been in print since their initial publications.

“This project has reminded me that what’s key is not the genre, but what opens up in rediscovery: so many people have been heartened by the reconnection to their writing, and in some ways, to our food,” Mara shares. “Helping make Doreen Fernandez and Edilberto Alegre’s work leap back to life is a vision already met!”

Fernandez’s books have long been notoriously difficult to find. Her earlier essay collection—arguably her most popular and accessible—Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture has been updated and republished by Anvil Publishing several times, most recently in 2020. Yet in the long stretches between reprints, copies remained elusive both here and abroad, with some secondhand sellers even pricing them anywhere from $300 to $500 (yes, there’s no mistake in the currency). Fernandez isn’t an isolated case; many works of Philippine literature have slipped through the cracks.

“Time does a lot to the chances of a book’s republication. Even with books of high significance, if their publisher folds, or shifts to another genre, or rarely looks back at their backlist, then the next thing you know it’s been decades,” Mara explains. “Sometimes the author also passes away and if a publisher is unable to locate their family, then republication is near impossible.”

Luckily, Exploding Galaxies was able to locate Fernandez and Alegre’s estates and secure the enthusiastic support of their family representatives. “I met with Maya Besa Roxas, who handles Doreen G.Fernandez’s estate [as her niece]; and on the side of Edilberto Alegre, I met Joycie Alegre and their son Lakan. They granted me the rights to publish the books,” Mara recounts.

The publisher was committed to preserving most of the original material, with very light edits. Not having access to any digital files, editors scanned, transcribed, and cleaned the essays themselves. The most noticeable change is a visual one: gorgeous, revamped designs and layouts that pay homage to the books’ past iterations while still staying recognizably contemporary for a new generation of readers.

“I had the great opportunity to work with two of my favorite designers: Miguel Mari for Palayok, and Kristian Henson (with Issy Po) for Sarap,” Coson explains. “I let them go with their instincts. Originally, Palayok had archival images; in this new edition, we have images of contemporary Philippine life by Jilson Tiu. For Sarap, the first edition had [artist] Manuel D. Baldemor’s wood cuts, so we went with four illustrators [Elle Shivers, Eva Yu, Gianne Encarnacion, and Kitty Jardenil] who made full-page photographs and flashes.”

Translating Culture Into Image

To say the new editions are beautiful would be a vast understatement. They’re fitting tributes to the complex mosaics of culture that the writers have built. In the case of Sarap, full-page, ornate illustrations in different styles are interspersed across the volume, not only providing a visual break but also added depth to the information presented: families enjoying home cooked meals, steaming bowls of comfort dishes drawn to appetizing perfection, and vibrant tapestries of intimate dining rituals. Even the glossary, usually the plainest part of a book, is brought to life through colored illustrations of dishes and objects by Kitty Jardenil.

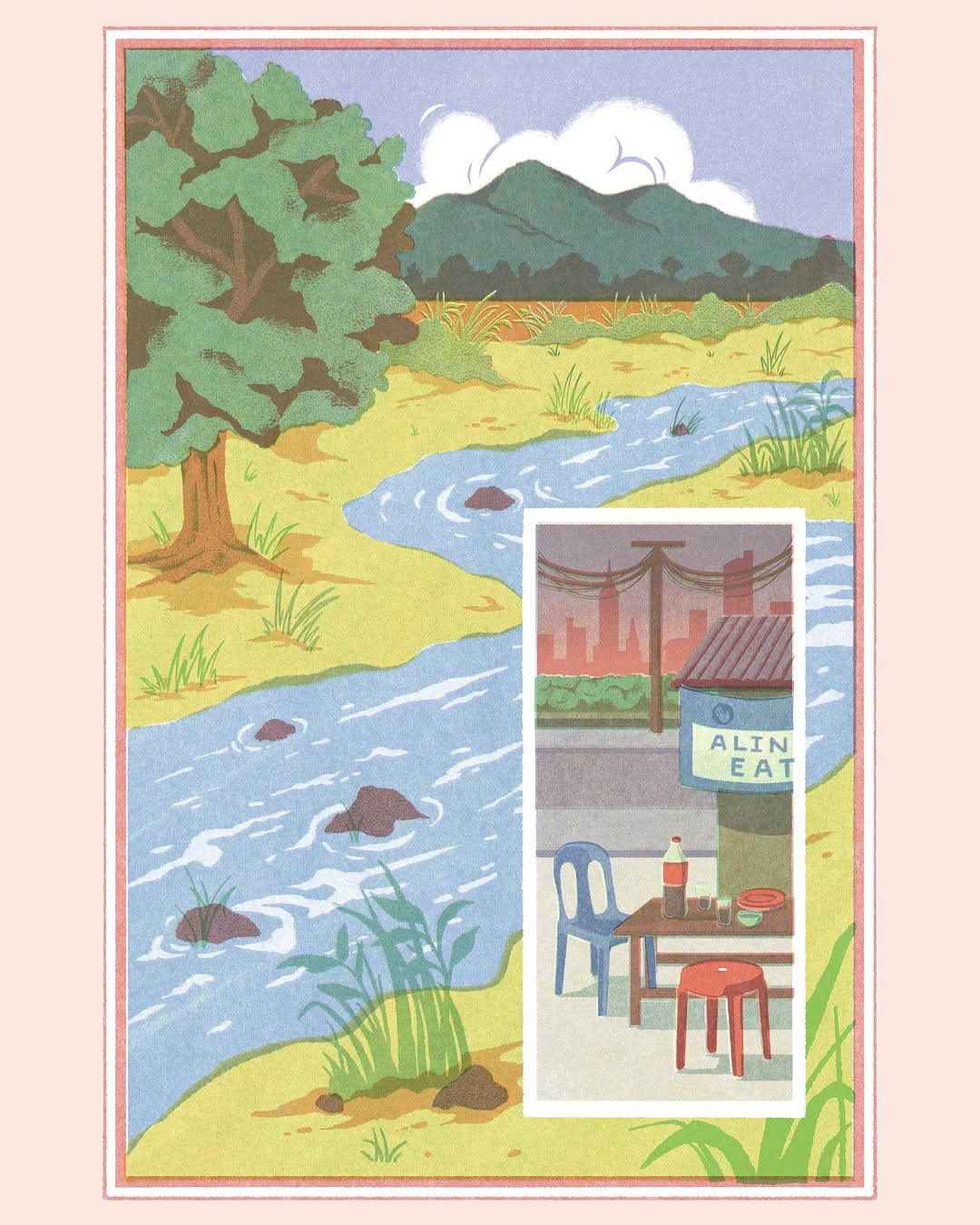

“When it came to the glossary, I did my best in making sure that the dishes and objects were recognizable. A lot of it was breaking them down to their most noticeable features, maintaining their distinct shapes, colors, and ingredients while still applying my own style and interpretation,” she shares with Lifestyle Asia. “I just hope people will point at each one of them and go, ‘Ah yes, that’s what it is!’” She also illustrated Fernandez’s essay “Poor Man’s Fare,” a verdant piece in a woodblock or risograph-like style contrasting scenes of nature and the city.

“I’ve written down a lot of quotes that struck me as Doreen’s words were like a punch in the gut, and still incredibly apt today despite the almost 40 years in between Sarap’s first publication and this edition,” she shares. “But the quote ‘The whole year the earth, the bamboo groves, the tall grasses, the trees offered food’ was what informed my illustration for the essay. Nature is reliable in providing sustenance, and knowing its systems and crevices will help keep a family fed all year round, in contrast with living in the city where food is not as rich and fulfilling. It was this stark difference that I wanted to capture with my illustration.”

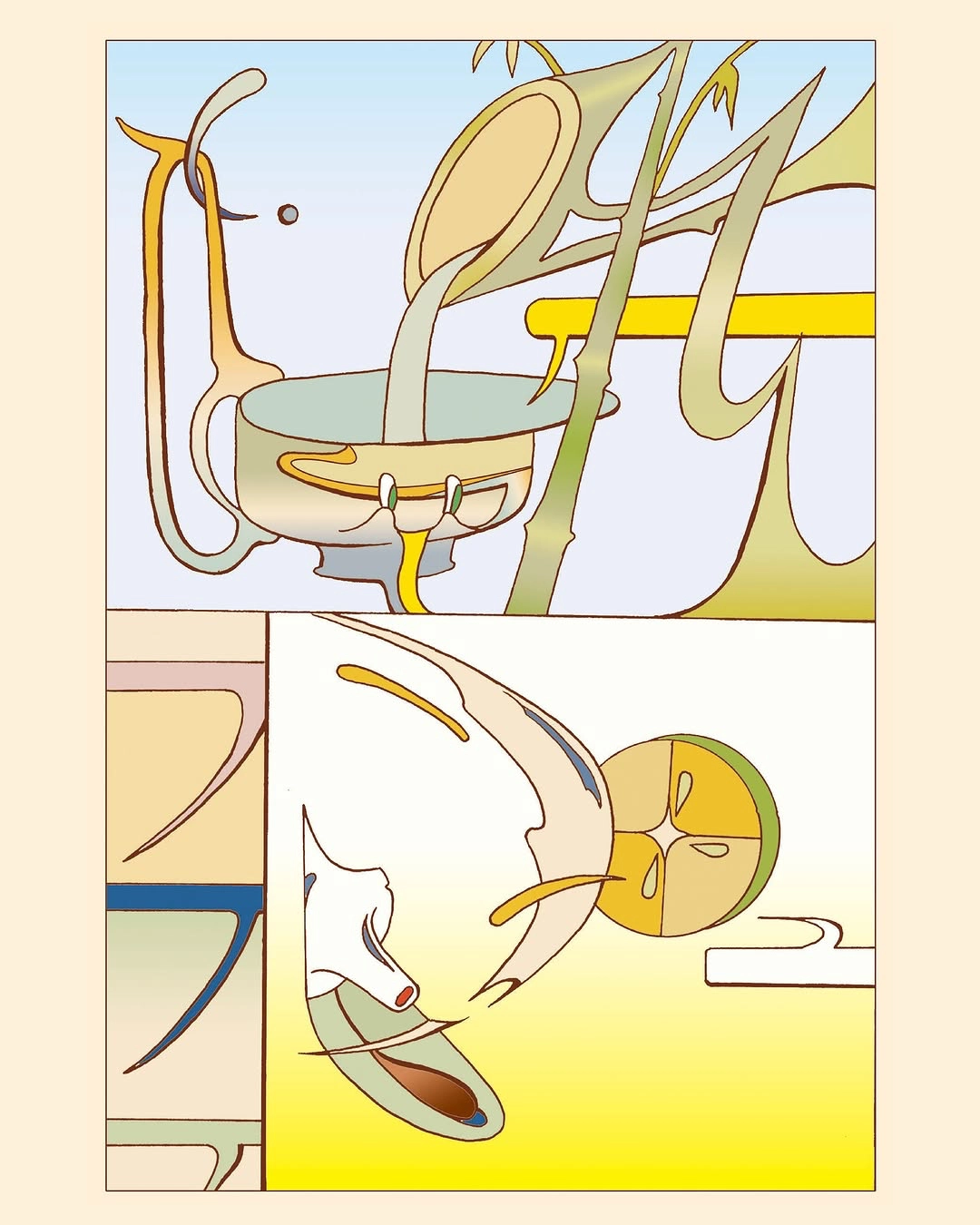

Artist Eva Yu’s motif-heavy work also takes inspiration from Sarap’s older edition. “I tried to reinterpret certain qualities of Baldemor’s woodcuts: the tight vignettes of produce, the tablescape and sharing. They all gave me a feeling of warmth and closeness. These were the qualities that inspired me to use almost cartoonish and flat images, to capture the nostalgia of luto lutuan.”

Meanwhile, photographer Jilson Tiu’s pieces take center stage in Palayok, infusing it with a sense of the “now” and highlighting the diversity of the archipelago’s culinary traditions. Glistening balut, vendors preparing raw produce in the palengke, a lechonero’s wooden cart, crowded Chinese eateries, piles of dried fish, and grains crushed against stone mortars in the mountains of Sagada, all depict how every corner of the country thrums with appetite and sustenance.

“I looked at the food heritage of Fernandez’s hometown in Silay, and took some keywords, like how important rice is in our culture, what makes Filipino food truly ‘Pinoy,’ how food is consumed in public, and how the mundane is appreciated,” Tiu tells Lifestyle Asia. “I translated her words visually by defining how food brings us together.”

A Conversation In Filipino Food

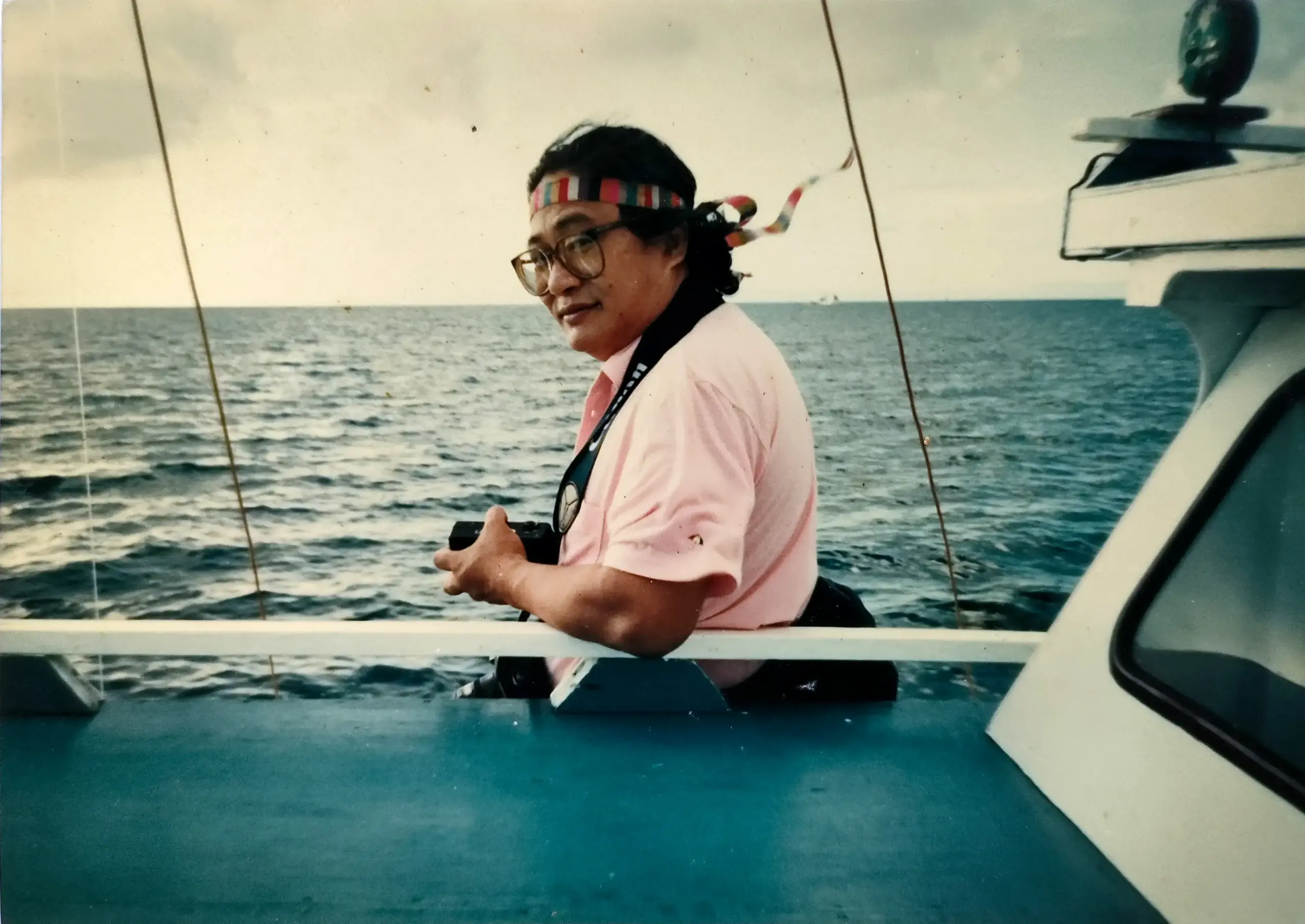

Sarap wouldn’t be the book it is without the indispensable insights and voice of Alegre, whom Fernandez collaborated with countless times, describing him as an “indefatigable editor, dear friend, and comrade of many battles.”

“I like to think reading Fernandez’s essays and then Alegre’s, as we do in Sarap, feels like listening in on a conversation,” Mara notes. “She was guided by history and he was guided by the field; they shared in the experience of deep discovery of where food comes from, how it’s made, how it tastes.”

Fernandez and Alegre devoted much of their lives to nurturing the Filipino food scene in its nascent stages, laying the foundations that would guide and inspire chefs, researchers, food writers, and lifelong learners for generations. To them, nothing was too “low-brow” to explore: every ingredient, every food stall, every seemingly simple practice, was treated with the same care, curiosity, and rigor that marked their scholarly and literary work.

Take Alegre’s meditative piece on Filipino drinking culture, “Pulutan: The Pleasure of the Changing.” He doesn’t just discuss drinking (inuman) and eating the unctuous bites that are part and parcel of the act—he expands them through the technical and figurative aspects of language itself. “Pleasure comes from a multiplicity of causes: the drink, the pulutan, the company, the talk. During the moment of pleasure, usually of extended duration, the causes are indistinguishable from each other,” he writes. “They merge, overlap, flow. Pleasure is a convergence, and ephemeral composition, a temporary intersection of the unchanging and the changing. Sensuality keen and sheer.”

Return to Fernandez’s piece on street food, or examine her essay “Why Sinigang?” The mouthwatering and versatile dish, so prevalent on our tables, becomes an elucidating case study of how the Filipino taste has been shaped—by season (sourness a refreshing break in the hot weather), land, and foreign influences—throughout history, as she argues: “Rather than the overworked adobo (so often identified as the Philippine stew in foreign cookbooks), sinigang seems to me the dish most representative of Filipino taste.”

One can’t help but admire the evident, contagious passion contained within Fernandez and Alegre’s writing—as well as wonder what they might’ve felt witnessing this glorious Filipino food boom.

“Like the best scholarly minds, they would be curious, observant, always learning, and interested in how the cultural landscape takes shape and why,” shares Fernandez’s niece Maya Besa Roxas. “Tita Doreen was also our biggest cheerleader, and I know she would be thrilled at the resurgence of appreciation and pride in the local, in what is our own—traditions, ingredients, crafts, markets, farmers and fishers, cooks, writers, our history, our stories. That we are learning to not take these for granted. That we are exploring what Filipino food means to us.”

Roxas adds: “It seems prescient, in a way. 25 years ago, Tita Doreen wrote: ‘Philippine cuisine will take on new faces and savors, but will always remain rooted in tradition, in the tastes and ways that assert its identity.’”

Bringing Something Special To The Table

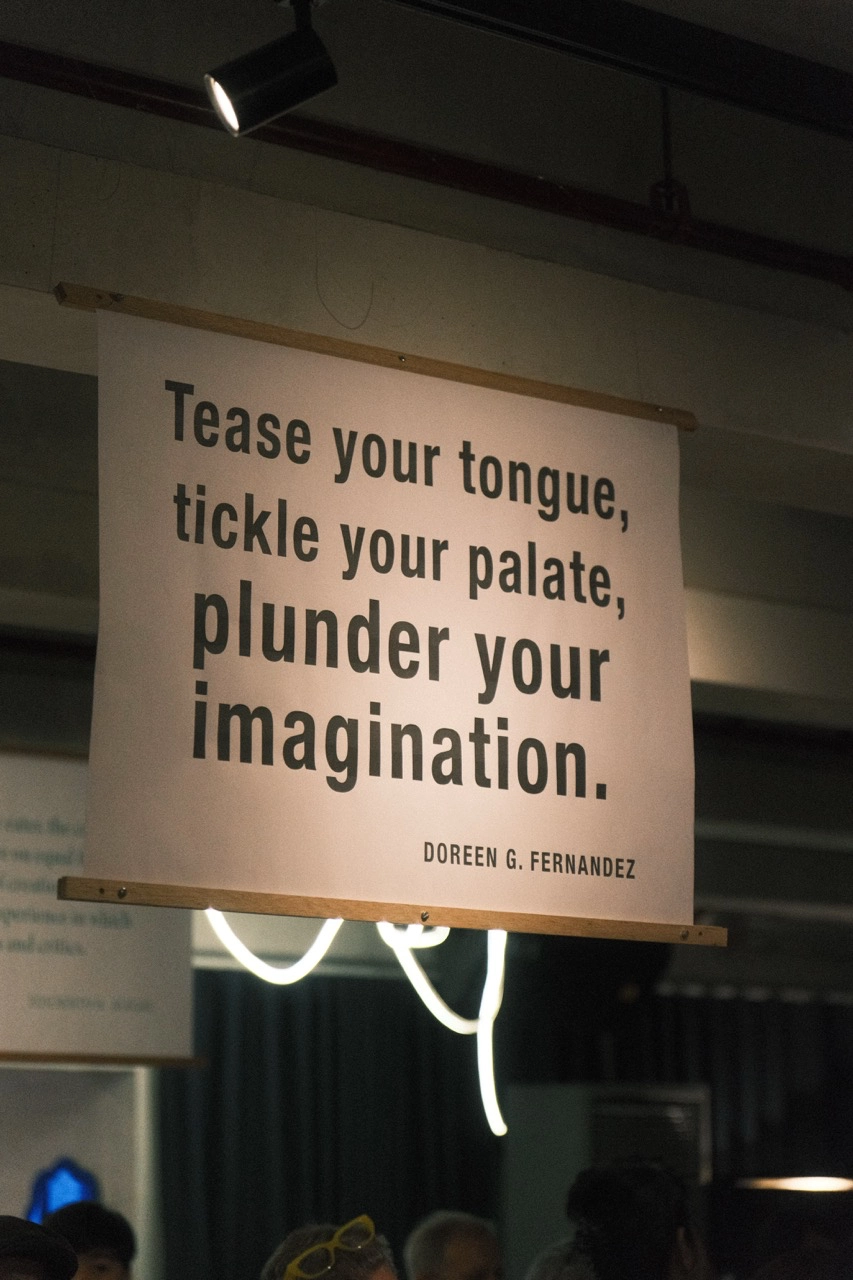

Exploding Galaxies’ two-book launch was a layered celebration of the country’s cuisine that did justice to Fernandez and Alegre’s works. Free flowing beer and wine abounded, as did classic dishes from Toyo Eatery and Manam. Scattered across the multi-floor venue at Karravin Plaza were a variety of activities and exhibitions: a fascinating display of pre-colonial pottery once used in meal preparation, an interactive tasting booth for Philippine vinegars, food-related film screenings, live readings of the writers’ works, panel discussions, and even grocery bag painting, among others.

Yet more touching than the thoughtful programming was the sheer number of visitors present that day. Students, academics, artists (National Artist for Dance Alice Reyes and photographer Neal Oshima were both present), chefs, old friends of the writers, fans of all kinds—if anything served as definitive proof of how much these two writers have given to the country’s cultural and culinary landscape, it was the sea of people who found pieces of themselves in their words. In turn, their own memories of the traditions, sensory details, and flavors explored in these books keep alive the ongoing conversation the two writers began decades ago.

This is where life imitates art, embodying the shared philosophy Fernandez and Alegre carried into their craft. “Writing about food involves mining one’s personal past, bringing memory to bear on the present,” Alegre explains in Sarap’s “Pulutan: The Pleasure of Changing.” Fernandez complements this line of thought in Tikim, writing: “Words that bear the culture within them need no adornment; they speak from the intimacy of the experience.”

I’ll end with a passage that inspired the title of this feature—also from Tikim, and one that sums up the true power, and secret, behind both writers’ enduring work: “Writing about food should not be left to newspaper food columnists, or to restaurant reporters. It should be taken from us by historians of the culture, by dramatists and essayists, by novelists, and especially by poets. […] If one can savor the word, then one can swallow the world.”

In honoring their words, we affirm that to taste, to write, and to remember are, in truth, one and the same act: keeping a culture alive by tucking its precious pieces into the personal and collective histories we carry with us.

This article was originally published in our December 2025 issue, with additional photos appearing solely in this digital feature.

Photos courtesy of Exploding Galaxies.