How the legendary artist brought surrealism to American cinema.

Perhaps no other artist is as readily identified with the Surrealist Movement of the 20th Century as Salvador Dali (1904-1989). Born in Figueres, Catalonia, Dali took his formal art education in Madrid and joined the avant-garde cultural movement known as Surrealism in 1929. The mission of the Surrealists was to assert the value of dreams and the unconscious through the juxtaposition of unexpected imagery; some notable names in the movement include French writer and founder of Surrealism Andre Breton, Belgian artist Rene Magritte, and American visual artist Man Ray.

As a Surrealist, Dali’s vast repertoire included painting, graphic arts, sculpture, photography, and design. In 1929, he and Spanish-Mexican director Luis Buñuel released Un Chien Andalou, a short silent film which gained notoriety for its non-linear narrative, macabre imagery, and a shocking scene depicting an eyeball being sliced by a razor blade. The two released another film in 1930, L’Age d’Or, a satirical comedy about the insanities of modern life and the hypocrisies of bourgeois society, however, the film was condemned by right-wing newspapers of the day who were outraged by its anti-religious theme.

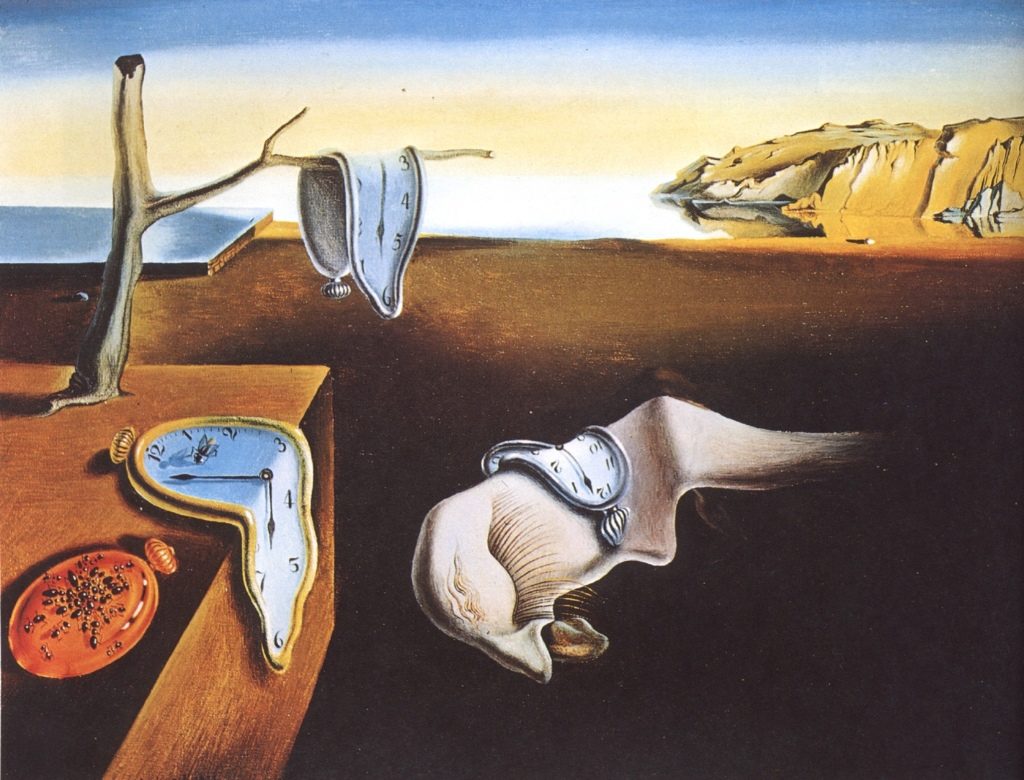

After the scandal of L’Age D’Or, Dali gained even more acclaim when he painted what is arguably his most famous work, The Persistence of Memory (1931). He went on to produce several more masterpieces in this decade, and soon, his fame as a creator of strikingly original artwork caught the attention of Hollywood filmmakers.

In 1940, Dali and his wife Gala moved from France to the United States to escape the Second World War. Hollywood soon came calling on the eccentric artist to imbue its films with his signature surreal style. His first project was to design a brief montage for the 1941 mystery Moon Tide. Dali’s sketches were deemed too bizarre by the film’s producers, and in the end, they diluted his ideas to be more palatable to American viewers. In the scene where the movie’s lead character gets drunk at a bar, Dali’s influence can be seen in the spinning watch and floating dress.

Dali’s next commission came from The Master of Suspense himself, Alfred Hitchcock. For his 1945 psychoanalytic thriller Spellbound, the British filmmaker had Dali design a fantastic dream sequence for the character played by Gregory Peck. Hitchcock explained his choice of artist to director Francois Truffaut in a 1962 interview: “I wanted Dali because of the architectural sharpness of his work…The long shadows, the infinity of distance, and the converging lines of perspective.” The dream sequence in Spellbound is brief but laden with symbolism: a curtain painted with giant eyes, blank playing cards, and an ominous shadow cast by a mysterious bird. Dali would go on to praise Hitchcock saying, “(He) is one of the rare personages I have met lately who has some mystery.”

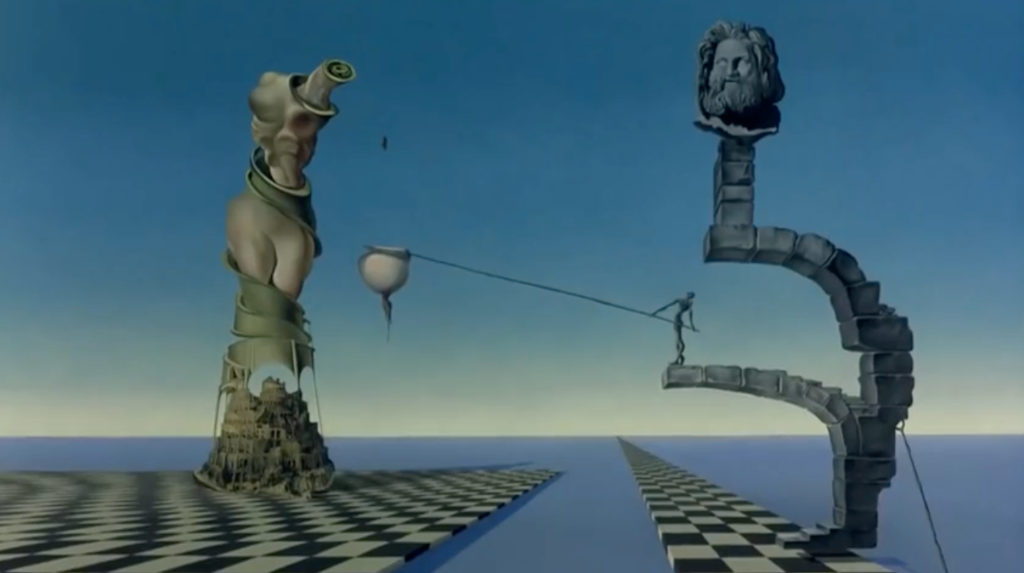

The third dream sequence Dali was commissioned to design was not for another studio-financed thriller; it was, rather unexpectedly, for a light-hearted comedy starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor. For 1950’s Father of The Bride, director Vicente Minelli asked Dali to create a nightmare montage. Although less surreal than the iconic sequence in Spellbound, this scene, with its sinking checkered floor and superimposed faces, is a dark, almost horror-like moment in an otherwise charming Hollywood product.

Sometime between Spellbound and Father of the Bride, Dali met animation pioneer Walt Disney. The two agreed to collaborate on what would become Dali’s most remarkable and recognizable work for a major Hollywood studio. In 1945, Disney hired the Spanish artist to sketch storyboards for Destino, a seven-minute animated film based on a Mexican ballad by Armando Dominguez. For this project, Dali worked closely with John Hench, celebrated for his styling work on Disney’s Dumbo, Fantasia, and Peter Pan. The two worked well together, but Disney grew increasingly exasperated with Dali because the artist would keep adding touches to the storyboard that the Hollywood mogul found too strange. When production costs soared, Disney pulled the plug on the film in 1946.

In 1999, Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew and a longtime senior executive at the company, unearthed the dormant project and decided to bring it back to life. With a story by Dali and his collaborator John Hench, Destino follows Chronos, the personification of time, and a mortal woman named Dahlia as they seek each other out across several surreal landscapes. The film premiered in 2003 and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film of that year. It is currently available to view on Vimeo.

In 1948, Dali and his wife returned to Europe. He would continue to contribute to films produced there, such as designing the sets and costumes for Don Juan Tenorio (1952). He also appeared in documentaries like Chaos and Creation (1960) and Impressions de la Haute Mongolie (1975). His participation in these films seems natural and organic; as a European himself, he is clearly at ease in this milieu. Looking back at his foray into Hollywood films, it becomes evident that the big American studios could only take this brilliantly eccentric visionary in small doses. Yet it was these small doses that introduced American and international audiences to Dali’s world, a world that is uncanny, irrational, unexpected, extraordinary…in other words, a world that is surreal.