From admiring an artwork, a digital image, to a video, you can now buy ownership of these works—but it comes with risks and at the cost of the environment.

During the 93rd Academy Awards, social media was abuzz for many reasons. One of which was on account of the NFT (non-fungible token) of the late Chadwick Boseman. The 3D digital tribute to the Golden Globe Best Actor was given as a gift bag to the Oscars’ nominees and guests.

Distinctive Assets, the company that supplied the tribute created by animator Andrea Oshea is not affiliated with the Academy. Yet they all received backlash online. Oshea’s intention was to “immortalize an artist… with art” and announced to auction a copy of the NFT. Fifty percent of the proceeds will go to the Colon Cancer Foundation. However, Twitter users expressed this move is triggering and commodified Boseman’s struggle with cancer and death.

Beyond the issue surrounding this tribute, NFTs have been prominently heard of lately. But what are these? Are these merely digital artworks? How come many express concerns over these?

ALSO READ: Token Explanation: Still Confused About Bitcoin? An Enthusiast Demystifies Cryptocurrency

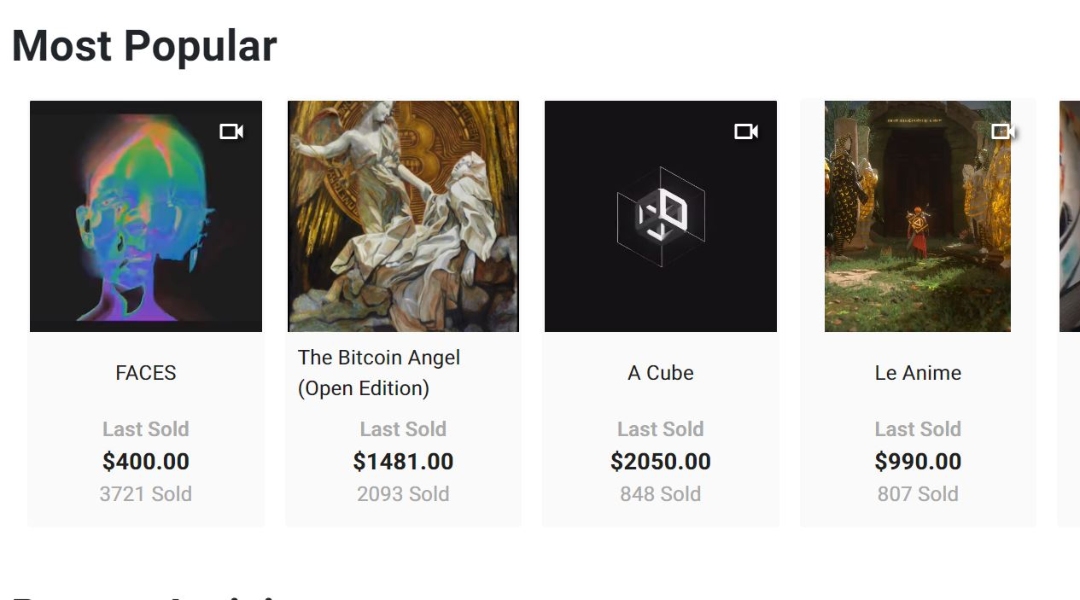

Can be worth millions

NFTs are assets with unique properties that can’t be interchanged like money. One can sell and purchase these but in the virtual space. Meaning, they have no tangible forms. These are similar to certificates of ownership for digital or physical assets.

Last February this year, the animated image of a flying cat with a Pop-Tart body, known in pop culture as Nyan Cat, was sold as an NFT for $590,000 in cryptocurrency. Similarly shocking is when Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s first ever tweet fetched $2.9 million in an auction.

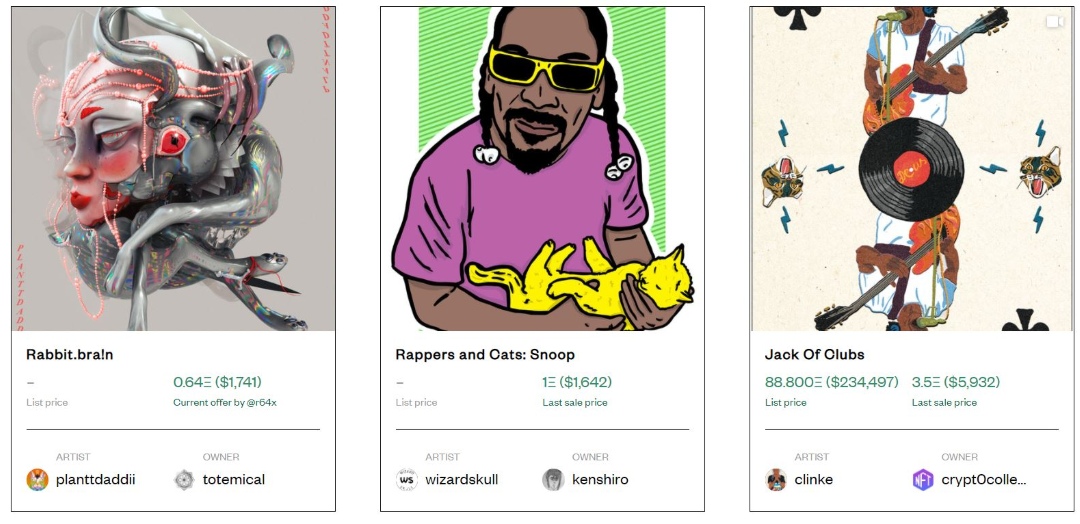

These assets can take the form of images, video clips, digital and physical art, and other collectibles. Buyers of NFTs receive tokens proving they ‘own’ the ‘original’ work. In some cases, artists can maintain the copyright over their work. They only have to sell them in cryptocurrency to allow others ownership of these pieces.

The transactions work similarly to bitcoin where records of ownership are stored in a public ledger known as a blockchain. This means records will not be forged as thousands of computers across the world validate this ledger.

Authenticity of creation

While selling NFTs can seem beneficial for an artist, these tokens bear issues including securing rights. For instance, stolen art on social media is not unheard of. But with the introduction of non-fungible tokens, artworks can be continuously reproduced without the artist’s consent and sold as NFTs. This allows more people to buy tokens, claiming ownership of the original works.

What makes this increasingly complex is there is no way to trace the identities of those involved. As with bitcoin, users are anonymous. Even when there is an honor system that allows a user to ‘mint’ an NFT and be acknowledged as the original artist, verifying authenticity is difficult.

To put it briefly, having someone ‘mint’ first doesn’t mean they are the original creators. This reinforces the long-time risk of using the internet: once you release something online, it is already subject to replication and distribution without consent and a multitude of security issues.

ALSO READ: What We Can All Learn From Tessa Prieto-Valdes’ Bout With An Instagram Hacker

A vulnerable market

Like any other online transactions, NFTs are prone to hacking. Multiple users of Nifty Gateway, one of the largest digital art marketplaces, reported getting hacked. Their accounts were used to sell their NFTs, buy more, and transfer to another account. The value of these tokens ranges from $10,000 to $150,000.

In their official statement, Nifty Gateway blamed the affected users for not setting up a two-factor authentication. In other accounts, a lost or hacked password for a digital wallet or credit card is possible to retrieve with the cooperation of the company, bank, or site owner.

The problem with NFT transactions, however, is their decentralized nature. There is no government, bank, or any other central authority overseeing this ledger. If one loses their account, then it is almost impossible to regain control.

Adding to the climate crisis

The largest impact of non-fungible tokens is, unsurprisingly, on the environment. Similar to cryptocurrency exchanges, a network of computers works by ‘mining’ or using cryptography to validate transactions. This uses a great deal of energy or electricity, estimated to reach 70 percent of power by clean sources.

Some crypto art collectors claim NFTs don’t have much impact on energy as there is only a tiny community of artists and collectors. However, transactions are not limited to buying and selling. Even artists release multiple ‘editions’ of their works. One may have released only four NFTs but have a total of 51 editions. Doing so equates to high power usage.

Ethereum, the second-largest cryptocurrency after Bitcoin, is the platform of marketplaces like SuperRare and Nifty Gateway. In turn, Ethereum’s total electricity usage is equivalent to 26.5 terawatt-hours or as much as the entire country of Ireland.

Artists and collectors alike don’t see the environmental cost. Many are unfamiliar with how miners use high-powered computers to convert fossil fuel-based energy into wealth. While cryptocurrencies like Ethereum are proposing solutions for this, its decentralized nature make it difficult to move people, especially miners, en masse to a more efficient process.

For now, it remains a matter of debate of who should lead and how to implement an eco-conscious system—if this is possible in the first place.