The piano-playing heartthrob was so loved, the fanaticism surrounding him birthed the word “Lisztomania” more than a century before “Beatlemania” became a cultural phenomenon.

There are some feelings and phenomena so overwhelmingly powerful that people need to coin a term just to capture them—maybe not in their full fervor, but just enough to paint a picture. Some time in 1963, the term was “Beatlemania”: now a part of our modern lexicon, the word was used to describe the intense fan frenzy that followed members of The Beatles during their heyday. Yet here’s a little-known fact: someone had already achieved this state of stardom more than a century before The Fab Four. Enter 19th century composer and pianist Franz Liszt, the prototypical rockstar whose fame, in many ways, played a large role in shaping the concept of the modern musical heartthrob.

READ ALSO: Paz Marquez-Benitez: A Filipina Literary Icon And Pioneer

A Classical Star Is Born

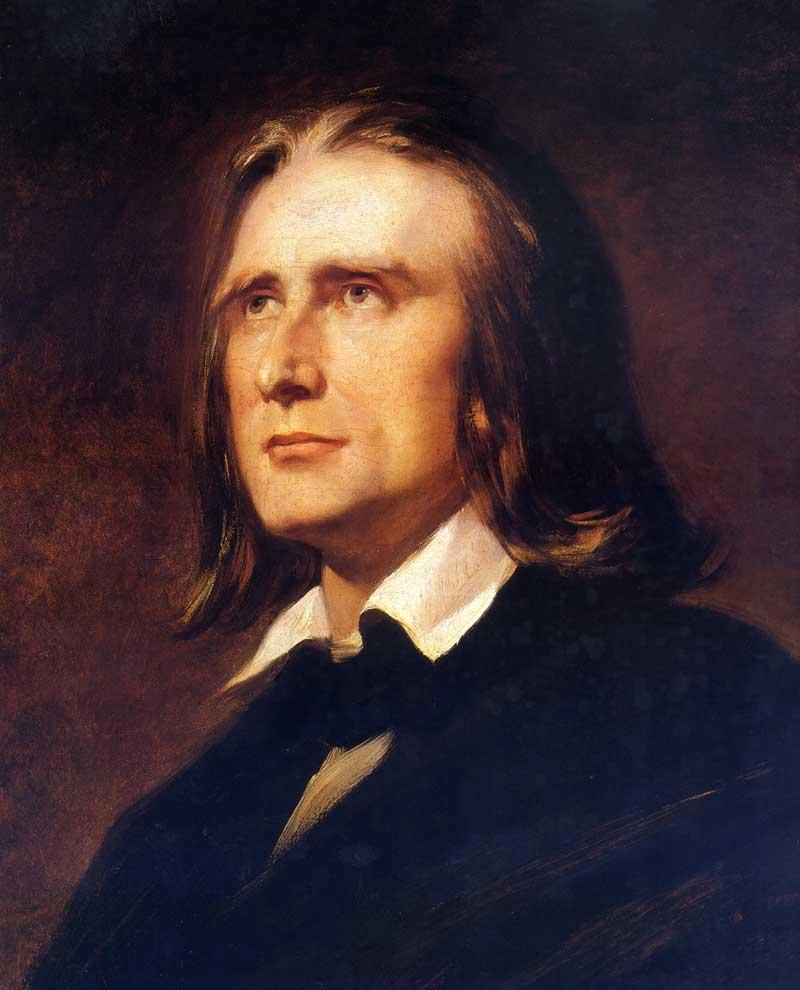

To cut to the chase, Liszt was more than a virtuoso pianist and composer: he was also, at least by the standards of his time (the 1800s), quite the looker. So it comes as no surprise that he garnered a devoted league of fans all across Europe. How devoted, you might ask? We’ll get to that later, but safe to say, those hordes of screaming, crying, swooning followers who’d kiss the ground The Beatles walked on weren’t exactly anything new.

Born in Sopron, Hungary on October 22, 1811, Liszt began his career in music at an early age, his father Adam Liszt being a skilled amateur musician and a court official of the Prince of Hungary (he played cello in the court orchestra, and piano at home). A young Liszt learned everything he could from his old man, and like any virtuoso, began stunning audiences at the ripe age of eight—composing his own pieces and performing them in public.

A few years later, his family moved to Vienna, where Liszt took lessons from classical greats like Carl Czerny and Antonio Salieri. By 1823, the young boy earned an impressed kiss on the forehead from Ludwig van Beethoven himself (which remained a point of pride for him throughout his career). His fame would only continue to grow, so much so that he no longer required travel documents to traverse from place to place and deliver his famous performances, as scholar Hannu Salmi notes in his paper “Emotional Contagions: Franz Liszt and the Materiality of Celebrity Culture in the 1830s and 1840s.”

What Makes A Musical Heartthrob?

Today, the idea of a pianist touring the world to give solo piano recitals isn’t something groundbreaking—but we have Liszt to thank for this. Scholars credit him as one of the first musicians (if not the first) to have kickstarted and popularized the practice.

That wasn’t the only thing Liszt did to make a statement. Part of his allure was the almost rebellious way in which he played the piano (truly the prototypical rockstar). As NPR details in an article, the musician made it a point to never bring his scores on stage, opting to play from memory instead.

Prior to this, it wasn’t the most favored approach—but with his chiseled features (displayed in full profile thanks to the way he strategically positioned the piano), long luscious locks, and dynamic performances (which involved plenty of dramatic head whipping), he made this once distasteful act something to behold (I guess we could use the word “sexy,” just this once).

To say that Liszt changed the way people viewed the musician as both performer and persona would be a vast understatement. During his peak, he transformed the act of playing an instrument into a spectacle that had crowds going wild, particularly the women who’d watch his concerts.

It might seem like a ridiculous thought: how titillating can a classical music performance possibly be? But it helps to remember that this was what was current at the time. Think of the ecstatic screams in recorded performances of The Beatles’s “Help!” or “Twist & Shout.” Even the band’s most avid fans today probably can’t replicate the exact reaction of those who saw it all unfold in real time during the 1960s. In other words, you just had to be there.

Lisztomania

Most of what we know about audience reactions to Liszt’s performances are based on extant written records; safe to say, they paint delightfully hilarious scenes that feel all too familiar (because fan culture is forever). If you think 19th century women weren’t unhinged, think again.

Fans reportedly fainted or passed out in their seats during his performances; threw their clothes on stage (some sources say this included underwear); and, well, pretty much tried to get every kind of memento they could from the man. We’re talking ripping bits of his outfits for keeps, saving locks of his hair, and fighting over pieces of his broken piano strings (Liszt had the habit of breaking pianos from the sheer force of his playing).

Even funnier, women would take home his used cigar butts, featuring them in wearable pieces like lockets and glass brooches, alongside his strands of hair and cameo portraits. Some fans even kept his leftover coffee in vials. Demand for his hair grew so great, he purchased a dog just to offer people some semblance of it without going bald.

Then, it happened: someone coined a term for the pandemonium. In a review titled “The Musical Season of 1844,” German poet Heinrich Heine used the word “Lisztomania” to describe what was happening as Liszt took Europe by storm.

“Truly it was not a German-sentimental, affectedly sensitive Berlin public before which Liszt played all alone, or rather accompanied only by his genius. And yet how powerful, how startling was the effect of his mere appearance! How vehement was the applause which greeted him! Bouquets were thrown at his feet,” Heine wrote. “The electric action of a demonic nature on a closely pressed multitude, the contagious power of the ecstasy, and perhaps a magnetism in music itself, which is a spiritual malady which vibrates in most of us—all these phenomena never struck me so significantly or so painfully as in this concert of Liszt.”

Women and Heine weren’t the only ones affected by Liszt’s performance; even the renowned Hans Christian Andersen once wrote in a diary entry, cited by Elizabeth Colledge in an article for Hektoen International: “When Liszt entered the saloon, it was as if an electric shock passed through it … as if a ray of sunlight passed over every face.” Yuri Arnold, a contemporary music critic at the time, also expressed his adoration: “As soon as I reached home, I pulled off my coat, flung myself on the sofa, and wept the bitterest, sweetest tears.”

The Messy Affairs Of A Celebrity

What’s a celebrity without the inherent chaos of fame and good looks? A true lover boy, Liszt had his fair share of paramours and affairs. In his 1903 book, The Love Affairs of Great Musicians, writer Rupert Hughs details: “Liszt’s life was so lengthy and so industriously amorous, that it is possible only to float along over the peaks, to touch only the high points. Why, his letters to the last of his loves alone make up four volumes!”

There were, of course, the sweet first loves like the only daughter of the Comte de Saint Criq, Caroline, whom he gave music lessons to when they were both seventeen. Sadly, the romance was stopped when her father politely pointed out their notable class differences (Liszt was by no means in the lower echelons, but his family was still noticeably less prominent).

The paramours were heartbroken, Caroline falling ill then recovering only to enter a loveless marriage—no doubt carrying Liszt in her heart until the very end. Even 10 years after their relationship ended, he wrote: “A female form chaste and pure as the alabaster of holy vessels, was the sacrifice I offered with tears to the God of Christians. Renunciation of all things earthly was the only theme, the only word of that day.”

From a young age, Liszt actually had dreams of making religion his career and entering the monastery. His parents were constantly trying to dissuade him from doing so, worried that he’d throw away his budding fame. Yet the heartbreak that came after Caroline was so great, he considered leaving everything behind, his melancholy making him a recluse. Liszt grew so sick that people were preparing obituary eulogies for him (an exaggerated gesture, but something that illustrated the gravity of his situation).

He eventually got better, as these things go; though like any young person nursing the wounds of a broken heart, Liszt leaned into the art of distraction (a glittering and busy music career laden with rebounds, hookups, affairs, and what have you). “He began a restless orgy of effort for mental diversion; all manner of theories and foibles allured him,” Hugh describes.

At the age of 20, Liszt was already touring the most artistic salons of Paris alongside his close friend, then 21-year-old Frédéric Chopin. It was around this time when the musician’s “snow-storm of love affairs” began—mainly with married noblewomen, including Comtesse Adèle Laprunarède and Comtesse Marie Cathérine Sophie d’Agoult (a woman whose beauty matched his looks and one who pursued him relentlessly).

Comtesse d’Agoult was so enamored with Liszt that she insisted to leave her husband and children and go into foreign exile with him. However, Liszt still carrying his principles, tried to dissuade her—though that didn’t stop public scrutiny, especially when d’Agoult and her husband officially divorced. Liszt married her, the two staying together until her death.

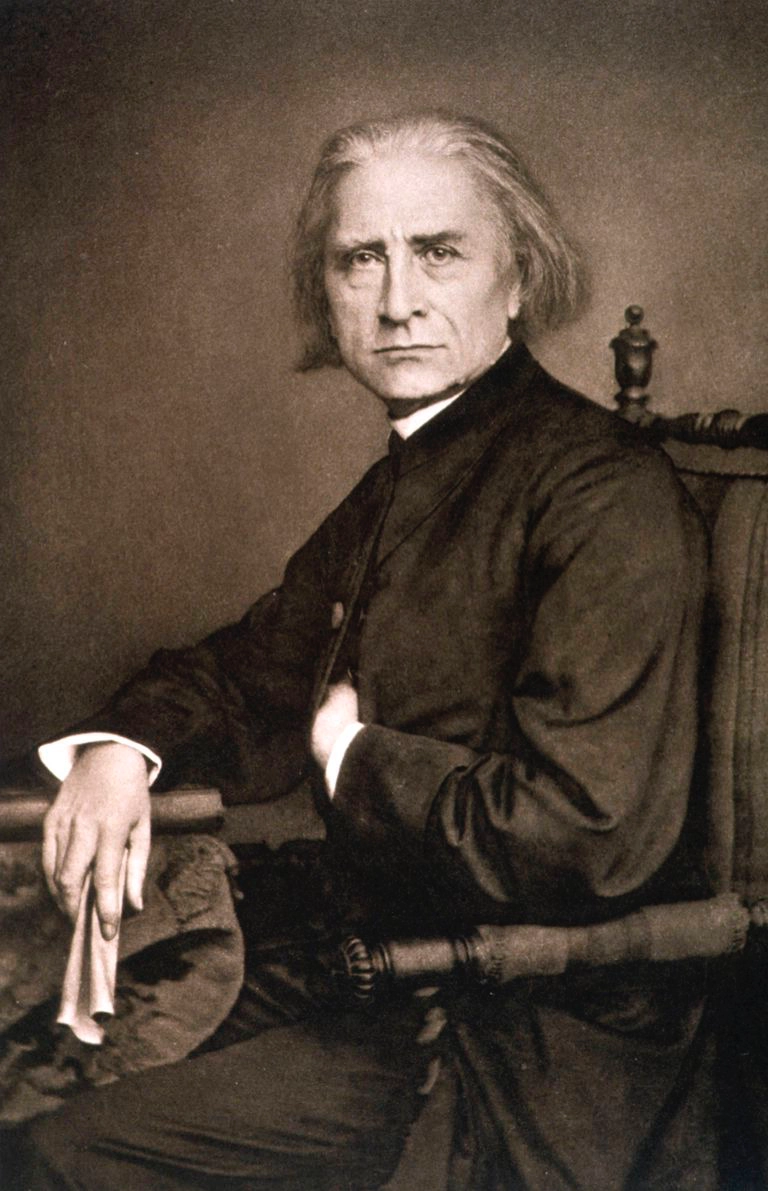

He’d later fall in love with Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein, a Ukraine-born woman of nobility who was unhappily married to Prince Nicholas von Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg-Ludwigsburg (he was seven years her senior). While she tried to get a divorce so she could marry Liszt, she was ultimately unsuccessful: they remained platonic partners, Liszt even entrusting her as “his sole heir and executrix” upon his death in 1886. Sayn-Wittgenstein would fall ill and pass away shortly after, requesting that a requiem Liszt wrote would be played during her funeral.

Trailblazer Until The Very End

Somewhere in between these affairs, and later on his music career, Liszt decided to focus more on his compositions and conducting. Yet he approached these new fixations with just as much bravado and innovation as he did his piano playing. Before he entered the picture, conductors simply oversaw performances, ensuring the orchestra stayed on beat. Liszt, however, approached the role like a sculptor or painter: shaping the way pieces sounded by adding his own artistic flair to the process, the way many renowned conductors do it today.

His roughly 1,400 compositions became shining examples of the 19th-century Romanticism that inspired him: passionate and emotionally-charged.

Liszt’s influence can be felt across pop culture, though maybe more subliminally than other artists. Those who watched Tom & Jerry might recall the 1947 short, “Cat Concerto”: the famous cat taking a seat by the piano with as much drama as Liszt did, before proceeding to play a snippet of his “Hungarian Rhapsody No.2” (one of 19 he created).

Director Ken Russell tried to adapt the musician’s heated love life into a campy 1975 musical-comedy film, Lisztomania (which wasn’t very well received, but the attempt was there). Then the composer-pianist was once again brought back into public consciousness through the hit alternative rock song of French band Phoenix, also titled “Lisztomania,” in 2009.

More recently, and the reason why this writer recalled the composer, animation students from the art school Gobelins made a stunning short tribute titled “VIRTUOSO,” which imagined what it might’ve been like to witness Liszt in action: his lithe hands flying across the piano, a crowd of excited audience members enraptured by the scene.

Clearly, Franz Liszt was more than a pretty face. It might’ve helped him gain popularity, yes, but it wouldn’t have worked without panache and pure talent—and hopefully, these are the things the world will continue to remember him for, besides being a musical debonaire.