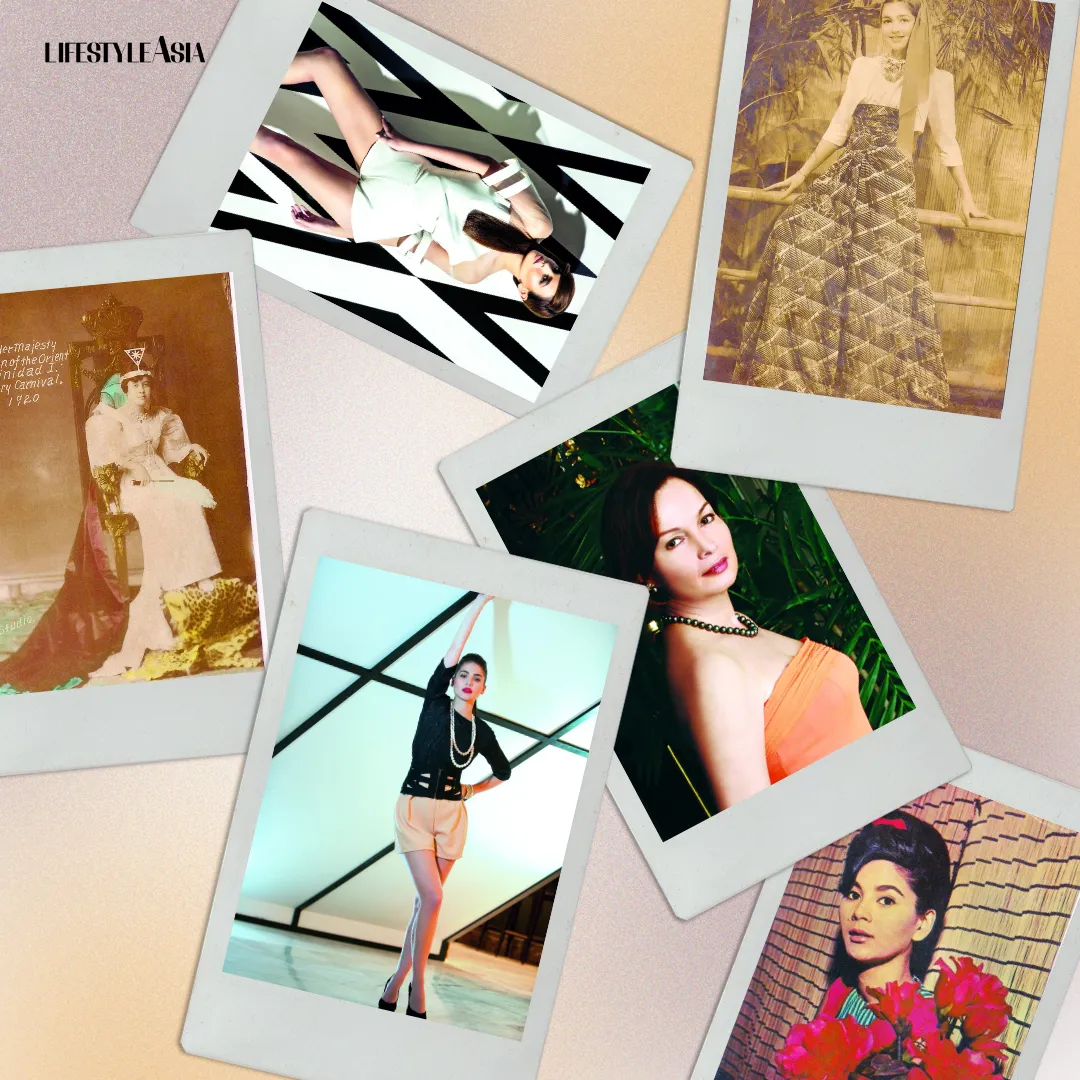

In our September 2013 issue, Jose Javier Reyes explored the changing meaning behind the term, and the faces of, the Filipino It Girl. From carnival queens to broadcast stars, what does it mean to have It?

We are defined by what we perceive or deem as beautiful. Who we are in the here and now is so completely different from who we were, say, five or even three years ago. There is nothing mind-boggling about that. Times change. Fashion (as an idea or an industry) keeps itself alive through and because of changes. We metamorphose not only because of our selves but as a result of everything that surrounds us.

This is why how we define and describe what is beautiful cannot be simplified by equations. What we marvel at and adore now is the product of so many growing and evolving expectations that are not only a matter of personal taste but also of social and cultural expectations. If we see the face and body of Anne Curtis on the covers of magazines, creating a continuous barrage of impressions on the big and small screens, or even filling the horizon while driving down EDSA, then it is because she is IT. Ms. Curtis has become the personification of the here and now—as she is our IT GIRL of this fleeting moment.

As we go down our history of popular culture, we realize that the It Girls are not merely pretty faces. They form that select club of particularly beautiful women hailed by the machinery of media and raised to the highest echelon of popularity by social clamor.

READ MORE: Rocio Zobel and the World She is Cultivating Back Home

The It Girl also points to what society and popular culture have become at that given moment. More so, she points to why we have become that way and what it is about her that has entrenched her persona into that revered and adored stature.

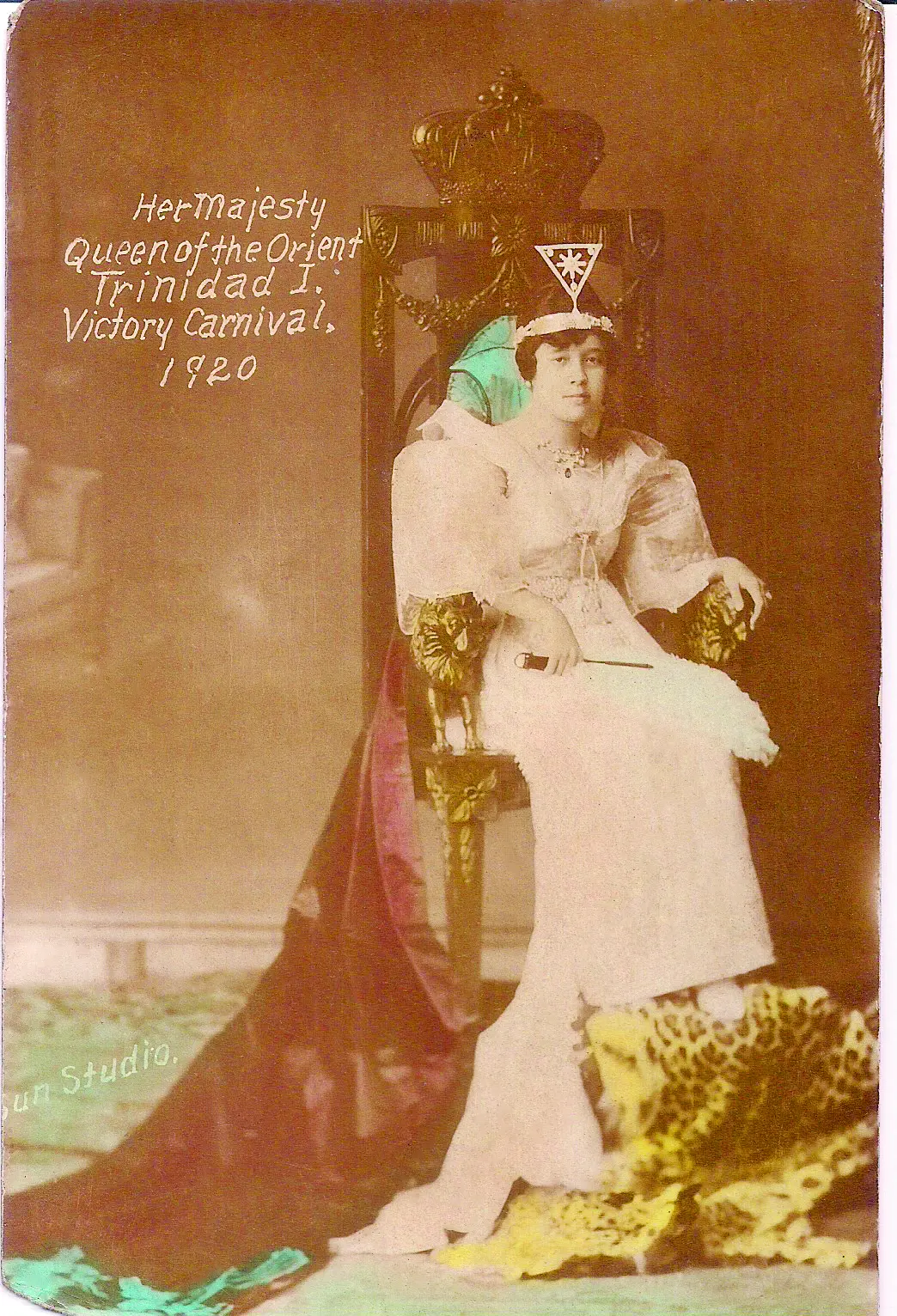

The First It Girl

During the first decades of the 20th century, the most celebrated young women boasted family names that spelled pedigree. Young ladies who come from families who matter—the next generation of illustrados to emerge from the process of Americanization—were crowned as the Reinas de las Carnivales (The Carnival Queens). Glamorized in their native baro’t saya and crowned with tiaras in fashion during the American Jazz Age, our It Girls were not the flappers from the other side of the continent but fair-skinned, well-educated, and respected mestizas who were the best and brightest (and therefore the most popular) debutantes of the country.

The earliest It Girls who were talked and written about, photographed, and sought-after were the most eligible bachelorettes whose premium went beyond a pretty face but the significance of their family names. Understandably, in a Manila that was more refined, genteel, and still living under the influence of very strong and marked class distinction, the It Girls were from the de buena familias (the good families) with aquiline noses, porcelain skins, and if not, the attitude and breeding that only came with education and wealth.

This tradition continued as Manila created legendary beauties like Susan Magalona, sister of the debonair movie star Pancho. Susan came from a clan associated not only with patrician good looks but also affiliations in politics and business. For it is in this gem of a beauty that the National Artist Nick Joaquin cited in an essay as the personification of society and beauty during Peace Time. Susan Magalona’s unmatched charisma represented those innocent and even frivolous years right before the trauma of the Japanese invasion. It is the benchmark of her beauty that became a turning point for a devastating change in the Filipino character, never to be regained or restored after the Second World War.

Model Citizens

The most popular ladies of the ’50s still came from the most revered families in society. However, the rise of cinema and the eventual birth of television changed the way people defined their lives as well as their priorities. A movie queen like Gloria Romero, then later on Barbara Perez, were launched and made into esteemed movie queens by their home studios, but were eventually picked up and made as ramp and photographic models by the fashion designers who dressed up the best and the finest in Manila’s society.

The crossover of movie and television personalities to the domain of society pages revealed the natural progression of media’s influence, cutting across strata of the population. There was still that very fine demarcation, however, between the popular artista and the alta sociedad (high society) icons who were idolized. In other words, there was the masa or the crudely termed bakya crowd with their movie goddesses, and there was the country club circle who dined at Nora Daza’s Au Bon Vivant, and found themselves dressed in specially designed clothes by Ramon Valera, Ben Farrales and Pitoy Moreno, immortalizing such names as Elvira Ledesma or Conchitina Sevilla or Joji Felix.

Even the models who graced the ramps were mestizas and mastizillas who came from the ranks of the audiences who filled the ballrooms of the Manila Hilton or Manila Hotel. Filipino couturiers used the daughters of their patrons and patronesses to emphasize the tradition of class distinction as far as expensive elegance was concerned. Gloria Romero possessed the looks and demeanor of the high society mestiza, and, well, Barbara Perez was already branded as the Audrey Hepburn of the Philippines: their inclusion in the exclusive circles of debutantes as fashion mannequins was more of an exception but already indicative of the culture of media celebrities yet to come.

This pattern continued all the way to the 1960s, when the It Girls were the likes of Pearlie Arcache and the entire sorority of Pacifica Models that toured the world with Joji Felix-Velarde as their organizer and mentor. The familiar names were still daughters of privilege, wherein fashion modeling was not considered a career but more of an on-the-job finishing school course for poise, elegance, and the art of meeting people.

Queen of Beauty

A turning point came when the daughter of Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil became the first Filipina to win an international beauty crown.

There was a time when beauty contests were also popularized by the daughters of the educated and the privileged. Gemma Cruz shall, to this day, remain an icon and an It Girl representing a generation that has long been replaced by loudness of volume brought about by the emptiness of substance. It was in Gemma Cruz’s victory as the country’s first Miss International that young ladies sent to represent our country in such pageants came from the well-schooled illustrados.

Beauty contests were college-bred kolehiyalas who were sponsored by top-name designers, groomed and presented to these competitions with the sincere hope of representing our country in the international arena.

Thus, it was not surprising to find winners like Aurora Pijuan, Gloria Diaz, and Margarita Moran wear their prized crowns. Their intelligence, charm, and elegance were not products of training but were inherent to their breeding and upbringing.

The It Girls of the 1960s to the 1970s were still junior socialites who managed to penetrate national media to gain a much wider popularity than the otherwise limited exposure provided by a single page covering high society events, photographed and essayed on broadsheets. Their national stature—the fact that they became more than beautiful faces but representatives of Filipino pride—somehow broke the lines that marked social and economic barriers. As made media became more encompassing and the members of the once reserved and highly exclusive stratum of society made themselves more accessible to television and print, the equations slowly but surely changed. Suddenly, it was no longer déclassé or baduy for the scion of a rich family to be featured on television or to make it to the pages of popular publications. As a matter of fact, magazines were born precisely to give space to the members of the special enclaves who were made accessible to the larger public.

To be rich and famous is to become a brand. In an age where there is only so much room available in media space, branding is all that really matters.

Turn of the Century It Girl

It was, after all, Anna Wintour of Vogue who had the foresight to understand the cult of the celebrity when she replaced beautiful but relatively anonymous fashion models as covers of the magazine she ruled over. By helping create the cult of the Supermodels, Wintour defined the It Girl as a product of hype and marketing. With the aid of designers like Versace, Valentino, and all the rest of the pillars of the international fashion scene, Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Cindy Crawford, and the rest of this bevy became brands to sell not only clothes but all forms of merchandising.

Suddenly, to be It is to be able to sell. You are the Girl of the Moment if you can push sales, promote ideas, but more so, become a product yourself. What followed was Wintour’s decision to put movie stars on the cover of Vogue, thus fusing popular culture with fashion—and the idea that good taste in the finer things is accessible to everybody because media says it is so.

The same phenomenon has happened in our country as a kind of permutation of the changing manner by which trends and tastes are shaped and created abroad.

The power of media—specifically television—has spawned an entire assortment of celebrities who are created within the confines of promotions and marketing machineries then sold to the public as media figures and celebrities. When television networks developed their own stable of contract stars, the It Girls no longer came from a spontaneous discovery amid the crowd but rather the packaging of a beautiful face supported by the complex machinery of numerous platforms of multi-media companies.

This also means that faces that defined the moment are no longer spontaneously found to flourish. They have all become part of the marketing machinery that is oiled to find the exact time when someone is launched, how she is sold to the public, and how he presents herself as a representation of a moment in the evolution of a generation. The moment can be split-second quick (as when the It Girl is a discovery of a reality show, a successful turn in a TV program, winning in a high-profile contest) or may take years and years of development and gestation.

Everything is now a matter of timing. And selling.

Selling the Drama

Anne Curtis, for instance, is not an overnight sensation. She has been around since she was 12 years old, appearing in tween roles before being prepubescent was fashionable. After more than 10 years, however, Anne Curtis came into her own not only by selling alone but because she was the right girl at the right time. The sweet little kid grew up to be this spunky young lady in short shorts and high heels, who can cater to the fantasies of the masa and enter the world of Republiq with equal confidence and aplomb.

Together with leggy ladies like Georgina Wilson and Solenn Heussaff, Anne Curtis has refined what It-ness means. No longer is she about being sexy and pouty: what is important is that whatever product she endorses (whether they are schools or condominiums) has greater chances of selling.

And that is what IT is all about. The power of the beautiful face to be a marketing force is what celebrity power has become. The charm is no longer to become an inspiration or aspiration: it is to wield power by just being who you are.

This article was originally published in our September 2013 issue under the title “Being It,” written by award-winning film director and cultural commentator Jose Javier Reyes.