From TikTok trends to lifestyle pressures, discover how self-betterment became a performance—and why the pursuit of perfection may not even be your own.

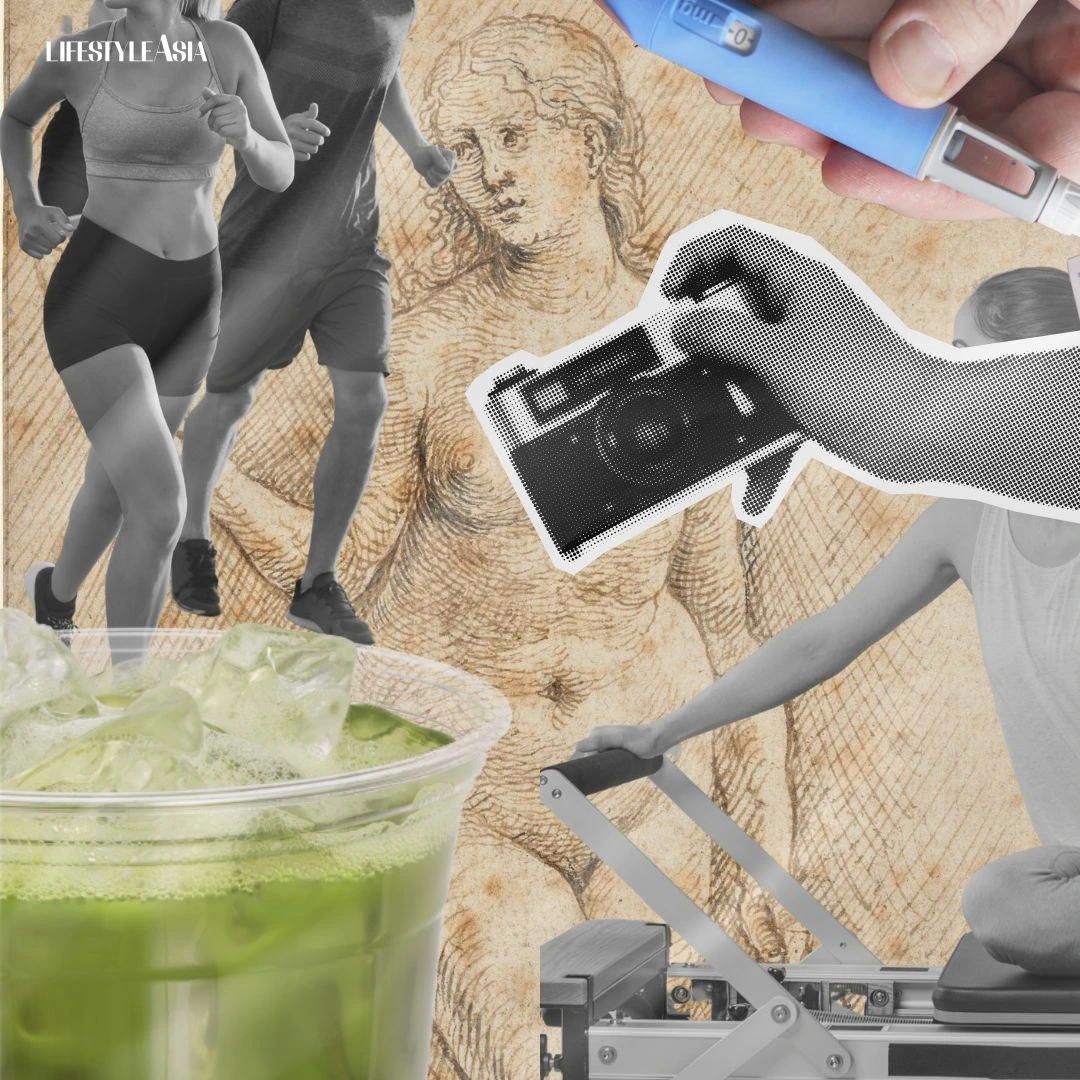

It’s Saturday and you’re having coffee by the window when you unlock your phone. The moment you open TikTok, you are bombarded with videos about run clubs, Pilates, matcha lattes, weight-loss drugs, and other self-improvement lifestyle trends recommended by the people talking at you through your screen.

You pause. There’s a feeling that starts to churn in your stomach. You feel pressured, maybe even left out. You ask yourself, “Am I not doing enough?” As you take another sip of your coffee—now wishing it were a strawberry matcha latte after watching an influencer in her Alo Yoga set order one post-Pilates—you get up and tell yourself, “I’m starting today.”

You try to follow all the workout recommendations from your feed, buy every trending skincare product, and schedule as many treatments as you can fit into a week—all signs that you’ve given in. You’re now a member of a cult: the Cult of Self-improvement.

Gone are the days when social media influencers are outright selling you a product with their promo code attached. Today, videos like “a day in the life” and “get ready with me” have shifted the paradigm—rather than selling products, the media is now selling a curated lifestyle. The strategy compels people not just to consume, but to conform.

READ ALSO: Facelift Epidemic: Timing, Feeling, And Alternatives

Why Self-improvement Is Soooo In Right Now

The idea that you need to purchase, experience, and conform repeatedly to achieve a certain level of self-actualization is rooted in capitalist origins. Through the lens of critical theory—a sociological framework that critiques societal structures, cultural norms, and power dynamics to expose oppression and challenge dominant systems—media today, especially social media, functions as an instrument for social control, driven by capitalistic gains.

Everywhere we turn, whether in the comfort of our homes or amidst the bustling anonymity of a subway commute, we are relentlessly flooded with information. This deluge, however, is not arbitrary; it is a meticulously crafted stream of promotional content, constantly nudging us toward consumption. We find ourselves living within the pervasive embrace of a promotional culture, an inescapable loop of reminders about the next acquisition we ‘ought’ to make.

“Whatever the content, all media content—whether billed as fact (e.g., news, interviews) or fiction (drama)—is advertising,” says Michelle Dillon in her book, Introduction to Sociological Theories. The consumption of advertising content disguised as “self-improvement” content has led us to falsely believe that we need to be in the same spaces, use the same products, and worse, live the same life as the people we watch. The result: a new kind of totalitarianism—cultural totalitarianism.

“Cultural totalitarianism crystallized by the creation of false needs and the attendant suppression of ideas and needs that are at odds with those mass-marketed as being necessary to the perpetuation of capitalism,” Dillon explained.

And so, when we open our phones—crowded with content selling a brand new lifestyle fad—we must ask ourselves: how many of these choices were truly ours, and how many were made for us?

Function Turned To Performance

At some point, you ask yourself, “Why am I doing this?”—as you get your blood drawn to see if you’re eligible for weight-loss drugs. Honestly, there’s nothing wrong with pursuing self-improvement. Striving to be the best version of yourself (physically and mentally) is always a worthwhile goal. However, if that pursuit is driven more by performance than by genuine intention, it may be time to reconsider your choices.

The relentless pursuit of perfection can be attributed to how we see ourselves. Sociologist Erving Goffman said: Life is a stage, and we’re all just trying to nail our roles. In his 1959 work, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, he breaks down how we all perform different versions of ourselves depending on who’s watching.

Think of it like social theater—we play specific parts, use curated routines, and lean on the right “props” (clothes, settings, body language) to sell the vibe. And just like any good performance, the reaction of the audience—whether they catch our cues or miss the mark—can make or break the whole act. Goffman’s take is a full-on dramaturgical lens: real life as one big, unscripted play.

That’s why, in an age where even running metrics are posted online, people push themselves to run faster and farther—striving for results that are “good enough” by the internet’s standards. We’re constantly performing for an audience—in this case, our followers.

In the end, it’s worth asking: are we improving ourselves, or just performing improvement for applause? When every step, every meal, every body check is shared and scrutinized, self-betterment risks becoming just another curated role we play. Goffman’s social stage has gone digital, and the lines between authenticity and performance blur with every post. Real growth doesn’t need an audience—it needs honesty.