As contemporary vintage fashion commands art-level auction prices and graces modern red carpets, a new generation of entrepreneurs and enthusiasts shift the definition of luxury fashion from the latest to the long-lasting.

Clothing is one of the most intimate reflections of a time, designed as we conform and react to our environment. The flapper dresses of the roaring 1920s reflected the growing freedom of movement for women, the “New Look,” which ushered in the post-war era, reflected a desire for luxury and return to femininity after the hardships of the war, and the power suits of the 1980s were a bold statement of the ambitious woman ready to rightfully claim leadership roles.

Fashion is sewn and embedded in the seams of history and can even capture the essence of the creative visionaries who defined them. This is evident in Madame Grès’s timeless draping techniques, emphasizing the natural silhouette of women versus the traditionally constricting formal dresses, and Phoebe Philo’s deep understanding of contemporary femininity that balanced a cool aspirational aesthetic with the realities of comfort and what women want to wear. These pieces tell an unspoken story of creativity and expression along fashion history.

READ ALSO: How This Atelier Is Innovating Made-To-Order Garments With Technology

Recently, however, there has been a curious phenomenon that seemingly defies the traditional relationship between fashion and time: an increase in appreciation for archival fashion. We are talking about clothing from designers’ and brands’ past collections that hold historical or cultural significance. We see more and more influential figures embracing vintage pieces: Zendaya in Bob Mackie, Kylie Jenner in Mugler, and Bella Hadid in Tom Ford-era Gucci. The trend extends beyond celebrity culture as auction houses report record-breaking sales for fashion pieces valued not for their connection to Princess Diana or Marilyn Monroe or Audrey Hepburn, but for their inherent artistic merit, fetching prices rivaling contemporary art.

This not-trend trend seems to be signaling a shift in how we perceive fashion’s cultural capital that again can draw comparisons to how we view, collect, and buy art. To explore this shift, we talked to distinctive voices in the space: Carlos Erquiaga of Archive Market and designer Jude Macasinag, who both navigate the world of collecting and dealing with archival fashion. We also spoke with entrepreneur Steffi Cua, a contemporary figure in Manila fashion who discusses how archival pieces transcend their original context to be part of her modern wardrobe.

The Spark That Started It All

While archival fashion on the red carpet might seem like a recent phenomenon and trend, for collectors like Carlos, Jude, and Steffi, their appreciation for fashion’s past began as deeply personal journeys.

“I started acquiring pieces for myself in the wake of Phoebe Philo’s departure from Céline [at the end of 2017],” says Carlos, who had been following and admiring the designer’s work since his college days. This personal passion evolved into a business, sourcing for international clients, as well as a curatorial mission through his Instagram platform Old Céline Market, where he showcased his collection and provided fashion commentary for his followers. What began as a specialized focus on Philo-era Céline expanded into Archive Market, his current business platform offering independently sourced contemporary-vintage and archival womenswear.

While Carlos’s journey began through passionate self-study of fashion history, Jude’s path was slightly more formal. While a fashion design student in Paris, he recalls a visit to “Alaïa and Balenciaga: Sculptors of Shape.” The exhibition explored the influence of Cristóbal Balenciaga, the master couturier, on Azzedine Alaïa, who inherited a heritage of architectural silhouettes and became one of modern fashion’s earliest archivists. Alaïa’s own collection of Balenciaga pieces shaped his design aesthetic, and this relationship sparked Jude’s fascination with how historical designs speak to contemporary fashion.

“I knew then that I wanted to start collecting fashion pieces myself to be able to physically learn from the work of other designers, specifically in the scope of haute couture [considered the highest form of garment making where pieces are handcrafted to exact measurements and specifications] which I have always been fascinated by yet haven’t had a lot of information about,” Jude shares. For the pieces he was able to collect in his size, he would wear them to better understand their construction and movement, informing his own approach to design.

Like Jude, Steffi’s appreciation for archival fashion developed during her fashion education, though in a different city and context. “Living in London and having access to historical clothing was a catalyst for me,” she shares, recalling her time as a business student at the London School of Arts, followed by her career as a buyer for the iconic luxury department store Harrods.

A 1998 Spring/Summer Dries Van Noten silk blouse and skirt set for £25, along with a 1980s Thierry Mugler jacket for £40, both of which she found and purchased online, set her collection in motion. “Archival fashion doesn’t have to be expensive if you know what to look for and where to look,” she adds.

The Passion-Fueled Process of Archival Collecting

Each piece of clothing is a unique artifact. For those who deal in archival fashion, like Carlos and Jude, building a collection is an art form, from sourcing pieces to curating and ensuring authenticity.

The hunt for archival pieces takes both dealers on different paths. “I like to go in-depth online, hunt in some of the most niche stores in Paris, and battle it out at auction houses,” says Jude, who shares these discoveries with his followers through his Instagram profile Couture in a Closet.

Meanwhile, Carlos sources his pieces from around the world with a specific curatorial vision in place from the get-go.

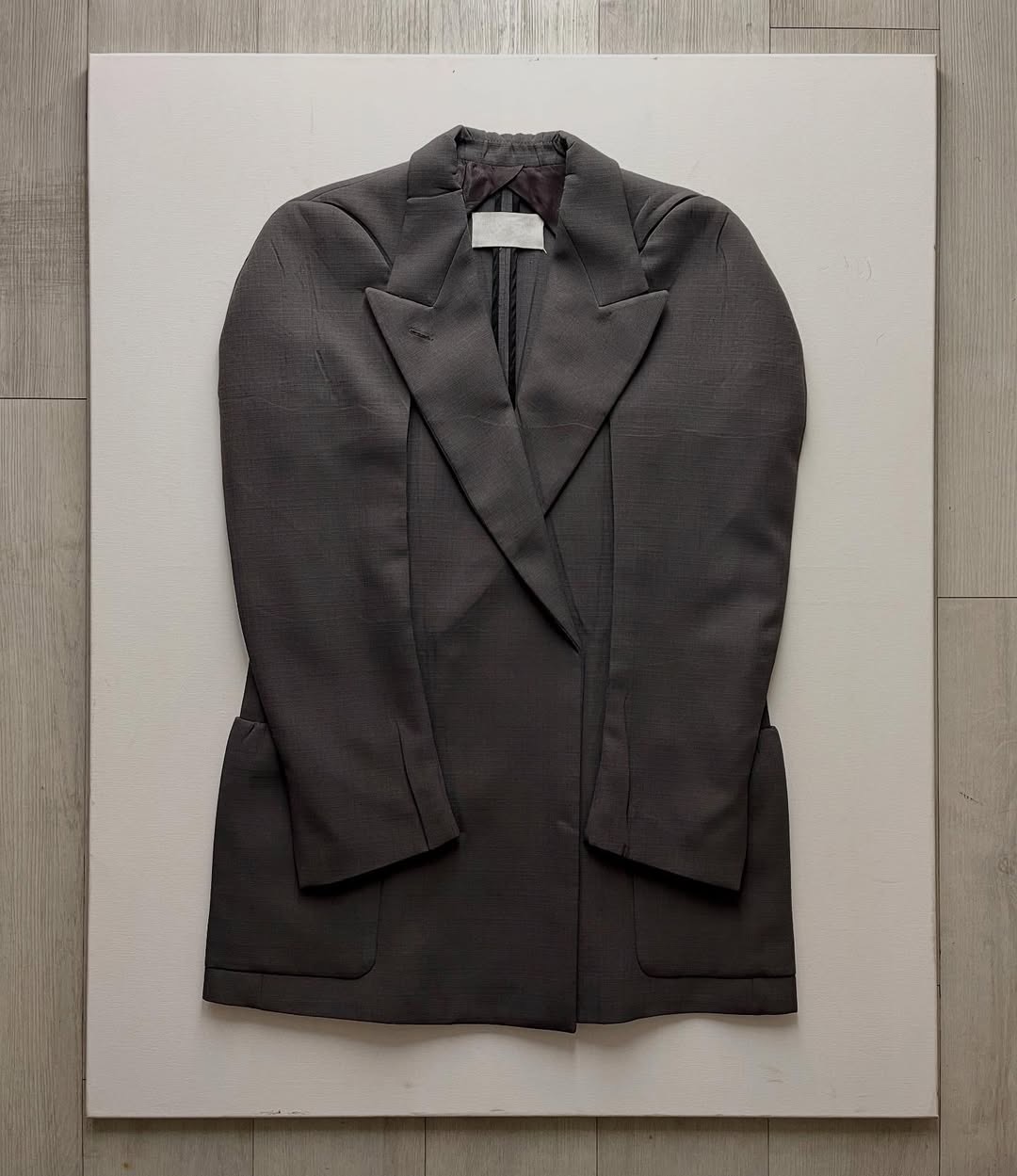

“What I find most fascinating is seeing how designers reinterpret functionality, or reference processes of making fashion in unconventional ways, with a level of restraint or sophistication,” Carlos shares. “I’ve found that pieces that possess these qualities tend to strike a balance between novelty and permanence. I feel that this allows for clothes to be equally interesting and useful, for them to exist in people’s lives on a pragmatic and wearable level.”

Jude’s curation similarly centers on craftsmanship, while also finding educational value. “I collect based on what I’m able to use for my work, whether it’s a simple 90s Yves Saint Laurent haute couture shirt made and fully lined with a layer of silk satin or an elaborate Madam Grès dress whose signature fine pleating I extensively studied,” he explains.

The authentication process reveals another contrast in their approaches. Carlos, for Archives Market, sources pre-authenticated pieces to avoid the hassle and ensure reliability for his clients. Jude prefers to build his authentication skills with experience. “Authentication is tricky,” he admits, “however, it’s a skill that is built up through years of formal or casual research. Although it’s not the case for all, it is also possible to develop an eye for authenticity just by constantly, physically seeing and comparing the works of other designers.”

The sourcing and authentication are just the beginning, as preservation is equally crucial in sustaining a collection. “The archived pieces are stored individually in their protective covers under low-humidity conditions, from which a selection is made available for purchase on the website,” Carlos notes, referring to his Archive Market platform.

Wearing Archival Fashion

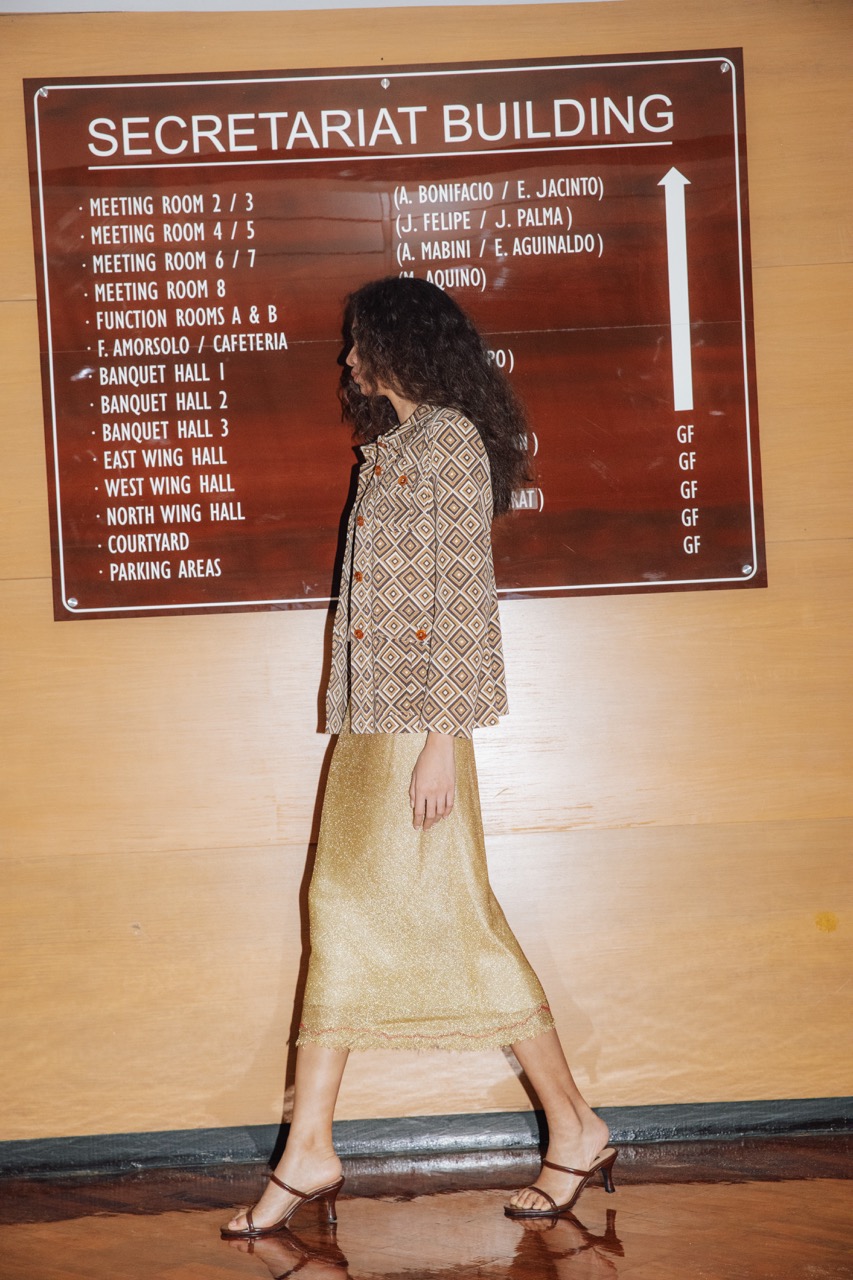

After examining the meticulous process of collecting and authenticating archival fashion, we turn to its most intimate aspect: wearing them. While some might view these garments as too precious, Steffi approaches her collection—which includes contemporary archival pieces from Alaïa, Mugler, Céline, Prada, and Miu Miu—with a balance of respect and practicality.

“I find great enjoyment in wearing archive pieces, but I treat them like any beautiful, contemporary piece. I’m sentimental about them, but not precious,” she explains. “It’s a form of expression, for sure.” While she maintains a slideshow of photos for inventory purposes, she recognizes that these are clothes meant to be lived in.

Jude shares his philosophy of bringing history into contemporary life. “It’s also about the fantasy of wearing certain clothes I once could only dream of accessing,” he reflects. “Everyone has their reasons, but for me, it’s a very personal thing to be able to wear and appreciate the jacket on my back, knowing that such a piece was made by trained hands. It creates a very special human connection and also gives a soul to an inanimate object.”

Carlos adds a similar perspective, noting how wearing archival pieces can connect us to specific moments in fashion history. They provide a retrospective glimpse into how designers approached their craft in different eras, from silhouette to textile selection, each element reflecting the cultural attitudes of their time that can be echoed and even reinterpreted by the modern wearer. He points to his clientele of “women in leadership roles with a deep appreciation or work in fashion, the arts, and related fields–from artists and gallerists to lawyers, CEOs, and designers.”

Archival Fashion As Living History

Archival fashion has evolved into a dynamic market where historical pieces live second lives. From Hollywood red carpet moments to the thriving vintage stores on the streets of Tokyo’s most stylish districts selling archival Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake. “I think, in general, whether it be fashion, furniture, or jewelry, there will always be a market for well-made things that stand the test of time,” Carlos notes.

In the Philippines, while we have museum collections and familial fashion archives—with grandmother passing on items to mother who passes them on to daughter—the market for archival fashion is still emerging. There is a slight but significant difference. While preservation through museums and inheritance maintains fashion history, an active market represents contemporary society’s broader recognition of these pieces’ worth. When archival clothing becomes a traded commodity, it transforms from a mere artifact to a validated investment, acknowledging not just its sentimental or scholarly value, but its position as a luxury good whose craftsmanship and cultural significance command real market power.

“Fashion history and archival is a form of human documentation most relative to our own bodies, and it’s time we are aware and take note of that when producing and preserving clothing culture in the Philippines,” Jude observes. Steffi adds a universal perspective: “Archival fashion belongs to no one and exists within all cultures.”

Just as the flapper dresses and power suits tell stories of their eras, today’s growing appreciation for archival fashion reveals our cultural moment. In an age of micro-trends and fast fashion’s disposable abundance, the rising market for archival fashion speaks to a deeper shift in how we value clothes. These pieces, finding their way into personal wardrobes, continue to tell their stories, now interwoven with new narratives by their contemporary wearers.

This article was originally published in our April 2025 issue.

Banner photo by Paolo Torio.