Slow fashion, fashion designers, and local textile artisans are intersectional parts of a tapestry called conscious consumerism.

It’s 11 PM, and you’re lying sideways on your bed, doom-scrolling on your phone. After a few funny videos on TikTok, you stumble upon a micro-influencer urging you to hop onto a fast fashion application. An over-enthusiastic voice suddenly convinces you that you need that miniskirt this summer. Before you know it, you’re on the checkout page, about to press “pay.” This seemingly innocuous moment, multiplied across millions of screens, fuels the relentless cycle of fast fashion that’s driving overconsumption and textile waste. In response to these troubling patterns, the rise of conscious consumerism and slow fashion has emerged.

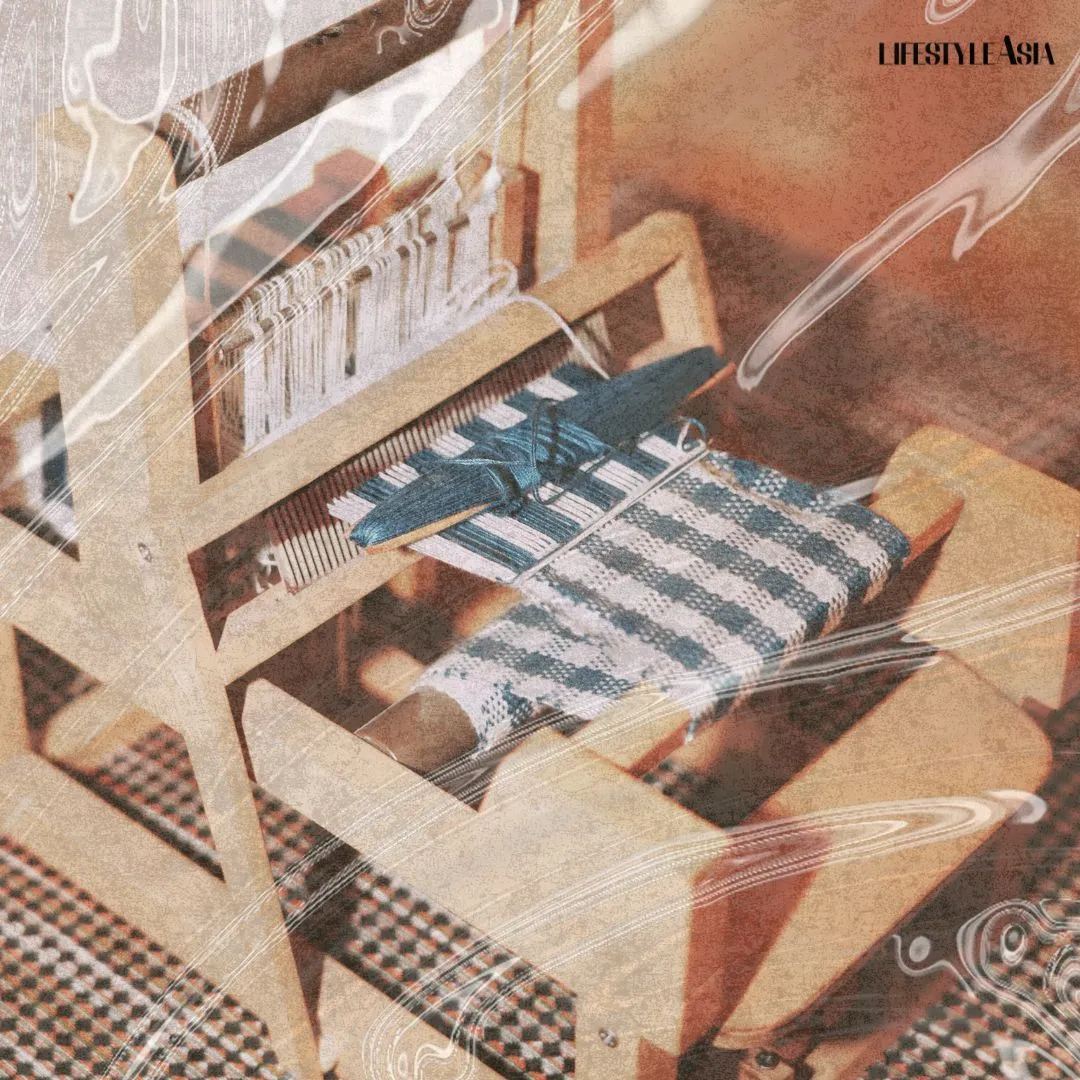

Across the Philippine archipelago, from Luzon to Visayas to Mindanao, practitioners of the slow fashion movement are collaborating with indigenous weavers and local artisans. We find representation through the work of three thoughtful designers: Paul Semira, Adrienne Charuel of Maison Métisse, and Wilson Limon of NIñOFRANCO. Embedded in these weaves are the stories and cultures of our artisans who meticulously handcraft every inch of fabric.

READ ALSO: Fashion’s Living Archives

Threads Of Fate Influencing Slow Fashion

For designers who work with indigenous textiles, firsthand experience with weaving communities provides invaluable insight that goes beyond aesthetic appreciation. This connection to craft and culture fundamentally shapes their approach to design. For Paul, Adrienne, and Wilson, fashion design is a passion-driven commitment of respect and a mission to uplift a slowly dying craft.

Initially, Paul Semira worked as a styling associate for a publication in Manila, honing his craft before taking the leap to pursue his lifelong dream of becoming a fashion designer. Today, he is the only fashion designer in his hometown of Ibaan, Batangas. His textile of choice for creating contemporary looks is Habing Ibaan, a locally-woven fabric that originates from the same municipality. Paul chose to center his collection and his identity as a designer around the textile out of local pride.

“Ang ganda ng pattern namin, yung sa Ibaan kasi may unique syang print na pag nakita mo sya masasabi mong, ‘Ah, it’s from Ibaan’,” he says. (Our woven pattern is beautiful, there’s a unique print that you can easily identify that’s from Ibaan.)

Meanwhile, Adrienne Charuel’s journey to becoming a fashion designer started outside the Philippines, attending École Supérieure des Arts et Techniques de la Mode (ESMOD) in Paris. Being immersed in an environment where fashion is regarded as a legacy and a craft gave her a deep, profound understanding of the art. This philosophy is reflected in her brand Maison Métisse, which focuses on sustainability, craftsmanship, and lasting cultural impact.

MAISON METISSE

Adrienne Charuel of Maison Métisse collaborates with in-house weavers and weaving communities across the Philippines, including from Abra and Aklan, to produce exquisite, entirely handmade pieces.

Photos by KIERAN PUNAY OF KLIQ, INC.

“I was drawn to a specific tribe in Abra because I wanted to learn about natural dyes in the Philippines, and they were one of the tribal communities that were trying to revive it,” she shares. “So I asked to do a three-day intensive course with natural dyes. And within those three days, I also managed to see the little weaving town.”

The experience deepened her love for incorporating indigenous textiles. Most recently, Maison Métisse released a collection using woven textiles from Aklan.

Another designer working to keep the craft of weaving alive is Wilson Limon of NIñOFRANCO. The Mindanao-based designer studied fashion design at the Philippine Women’s College of Davao, where he presented a capsule collection inspired by the diverse attire of 11 ethnolinguistic tribes in Davao, with a focus on the Bagobo Tagabawa tribe.

He was excited to work with the tribes, admitting that he initially knew little about them aside from seeing them during local festivals. For his collection, he connected with the community and learned more about the untapped weaves they produced. Little did he know that this college project would lead him to create his brand and present many opportunities, both for him and the local weaving community.

Winding The Resources For Slow Fashion

The collaboration between traditional textile weavers and modern designers demands respect for the cultural significance of the artisans’ lived experiences and the community that each inch of fabric carries.

In sourcing textiles, Paul’s proximity to the Habing Ibaan weavers isn’t merely convenient—it’s intentional, reflecting his commitment to place and community.

“Actually, ang maganda kasi nito, malapit lang sa shop ko, sa lugar na tinitirhan ko, yung mga habihan. So madali siyang puntahan,” he shares. (The good thing is that my atelier is close to their homes, the artisans. So I can easily go there.)

“Pag sinabing ‘Batangas,’ ang masasabi lagi balisong, Bulkang Taal. Pero ngayon pag sinabing Batangas, pwede nang sabihin ang Habing Ibaan.” (When you think of ‘Batangas,’ you automatically think of butterfly knives and the Taal Volcano. Now, when Batangas is mentioned, the Ibaan weave can be part of the conversation.)

Similarly, Wilson maintains direct relationships with the Bagobo Tagabawa tribe. “I work directly with the weaver. We don’t have a middleman,” he explains.

NIÑOFRANCO

Wilson Limon of NIñOFRANCO blends traditional craftsmanship with modern aesthetics, showcasing woven textiles from communities such as the Bagobo Tagabawa ethnolinguistic group in his contemporary designs.

Photography by BELG BELGICA Courtesy of NIÑOFRANCO

This unmediated connection allows Wilson and Paul to build meaningful collaborations, exchanging ideas with artisans and exploring ways to maximize the creative potential of the woven textiles they use.

Adrienne, on the other hand, takes an integrated approach. As a weaver herself, she brings a practitioner’s understanding to her collaborations with artisan communities. She primarily sources her textiles in-house in her atelier. Adrienne employs and supports single mothers who learned weaving through the Philippine Textile Research Institute.

“They attended some weaving sessions and resonated with it. I feel like weaving can also be psychological, sometimes, or maybe in general [it’s a form of] escape,” Adrienne says. “You’re just in the place where you’re creating something that’s between you and your art. I guess it sometimes connects with the right people.”

Why am I a weaver? Why am I telling my story?” Adrienne reflects on navigating the complex cultural contexts of traditional textiles. “Why am I telling the stories of the women and the communities around me? It’s so that they won’t be forgotten. I continue to educate and raise awareness through workshops, because I want the weaves to be remembered.”

In Mindanao, Wilson’s work with the Bagobo Tagabawa tribe shows this delicate balance between honoring tradition and creating contemporary expressions. When collaborating with T’boli weavers alongside the Bagobo Tagabawa, he met some who were reluctant to use cotton for traditional patterns. In the process, Wilson engaged in dialogue to understand cultural boundaries so he can best promote the craft in a modern way.

“When the public thinks of, for example, T’nalak or Inabal weaves, they just think of tapestry, like table runners,” Wilson says. “So I want to think of something that people can use on an everyday basis, like clothing, for more awareness that we have this kind of artistry here in Mindanao.

Weaving Through Challenges Of Slow Fashion

Even with all their efforts, local designers and artisans still need support, particularly with the obstacles that slow fashion and the local weaving industry face. Paul sheds light on the existential threat they face: the aging demographic of weavers and the lack of generational transfer.

“Kasi ang mga weavers namin dito 73 to 75 years of age, tapos pinakabata 45. Wala na mas bata sa kanila na willing mag-aaral at matutunan yung industry o kultura ng paghahabi,” he notes sadly. (Our weavers are around 73 to 75 years of age, with the oldest being 45. No one younger is willing to study and learn the industry or culture of weaving.) With fewer than 20 weavers in Ibaan, the craft stands on the brink of extinction.

PAUL SEMIRA

Paul Semira is dedicated to preserving the tradition of Habing Ibaan by collaborating with a small team of weavers, ranging in age from their 40s to 70s, and integrating this heritage textile into his modern and everyday wear designs.

Photos courtesy of The Provincial Tourism Board of Batangas and Paul Semira

Beyond these practical challenges lies the broader issue: the need for comprehensive support for all artisans across the production chain.

“That’s such an important part, of course, to support the communities. But when it comes to brands that are also trying to sustain the craft, people tend to forget the team behind the brand,” Adrienne points out. “I think people often overlook that it requires a lot of work to transmit the knowledge. Social entrepreneurship is not easy.”

These designers and their brands represent a crucial bridge between traditional artisans and contemporary markets. “That’s our lifelong vision,” Wilson says. “We want to transform a Western-minded Philippines into a culturally enriched nation that provides livelihood to these individuals because they safely keep the true art of the Philippines.”

The Power Of Consciously Choosing Slow Fashion

Part of the solution lies in shifting consumer mindsets. By making thoughtful purchasing decisions, we can help revive dying crafts and empower communities across the archipelago.

“If people support brands that do a lot of hand-weaves or support traditional weaves, they’re actually supporting a legacy beyond the brand,” Adrienne says. “You’re helping artisans thrive, and more than that, you’re helping the craft thrive on its own.”

Slow fashion is a movement that values the entire ecosystem of creation: the artisans who maintain centuries-old techniques, the designers who translate these traditions for contemporary wardrobes, and the conscious consumer who completes this virtuous cycle with their mindful choices.

Or, as Paul simply puts it: “Kailangan muna magsimula sa atin.” (It should start with us.)

This article originally appeared in our June 2025 issue.