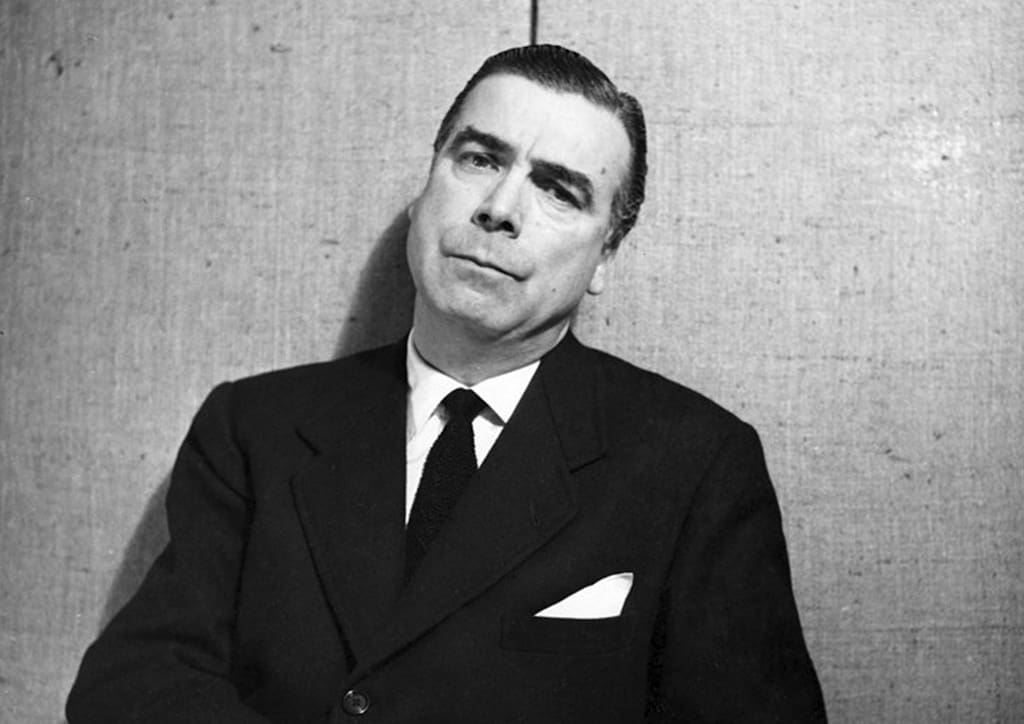

Cristóbal Balenciaga was once described by his contemporary Christian Dior “as the master of us all.” Despite living a life in the limelight through his innovative contributions to the world of fashion, Balenciaga was actually a very private person. He was a quiet genius, garnering a reputation as a meticulous perfectionist, whose mind ticked with a little bit of madness. A madness that allowed him to dream up pioneering couture that would change the scape of the fashion business forever.

The Seamstress’s Son

Last year, acclaimed filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson released Phantom Thread, a drama about a scrupulous fashion designer named Reynalds Woodcock, who dressed socialites and royals in avant-garde designs in 1950s London. Daniel Day-Lewis played the role to much effect, showing Woodcock’s perfectionist nature and often monstrous behavior towards those who worked under his House. Albeit entertaining, many viewers were not aware that the film was actually loosely based on the genius of Cristóbal Balenciaga, one of the 21st century’s most iconic designers. He was Woodcock in real life, fussing over fabrics, patterns, and the craftsmanship that goes into the work of his beautiful gowns. His reputation spread throughout the world during his illustrious career. Although fashion lovers were in awe, many found his behavior utterly dumbfounding and often, disturbing.

Balenciaga was born in the fishing town of Getaria, Spain in 1895, and just like Gianni Versace his mother was seamstress. As a child, Balenciaga was encouraged to work with her and he quickly learned her craft. Soon, the young designer was a notable town personality, even garnering the attention of the Marchioness de Casa Torres, a noblewoman, who became his patron. She eventually sent him to school in Madrid to perfect his craft.

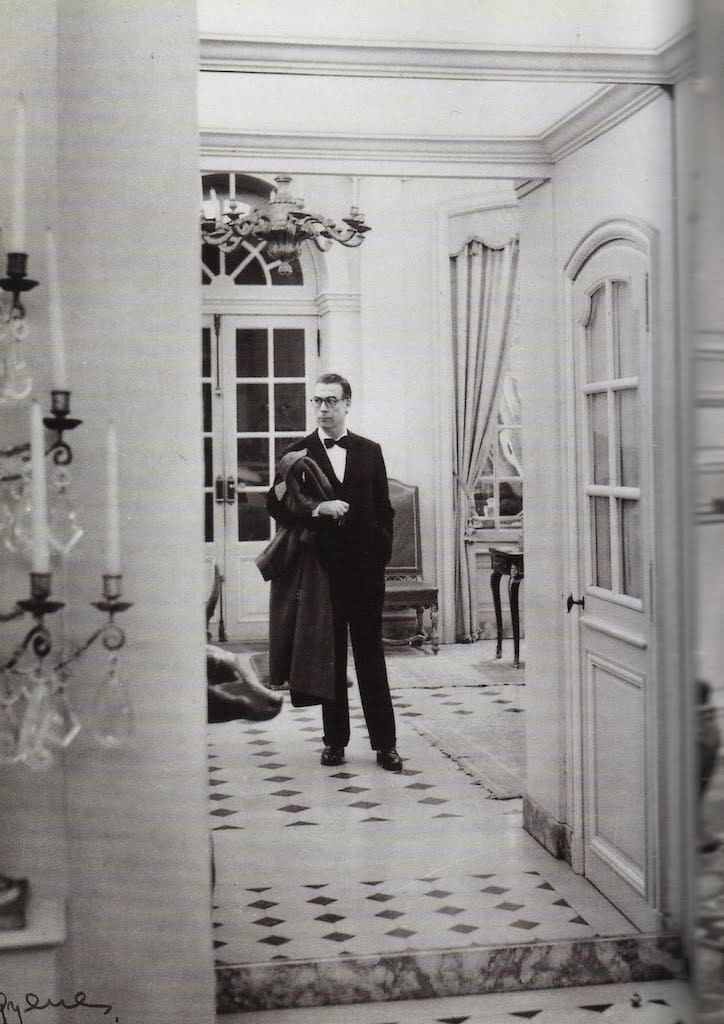

By the time opened his first shop in San Sebastian in 1919, he already had 20 years of experience in tailoring and cutting patterns. There, he opened Eisa, a more affordable version of what was to be his works inside his Paris maison years later. Members of the Spanish royal family soon started commissioning the young designer for their personal clothes, making him a sought-after couturier in him home country. He soon expanded his stores into Madrid and Barcelona, but was forced to close them during the arrival of the Spanish Civil War. Balenciaga, however, endured. Just like any wide-eye couturier, he made his way to Paris, the fashion capital of the world. The first House of Balenciaga opened on August 1937 at Avenue George V.

RELATED READS: Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn: A Love Story

A Fashionable Calling

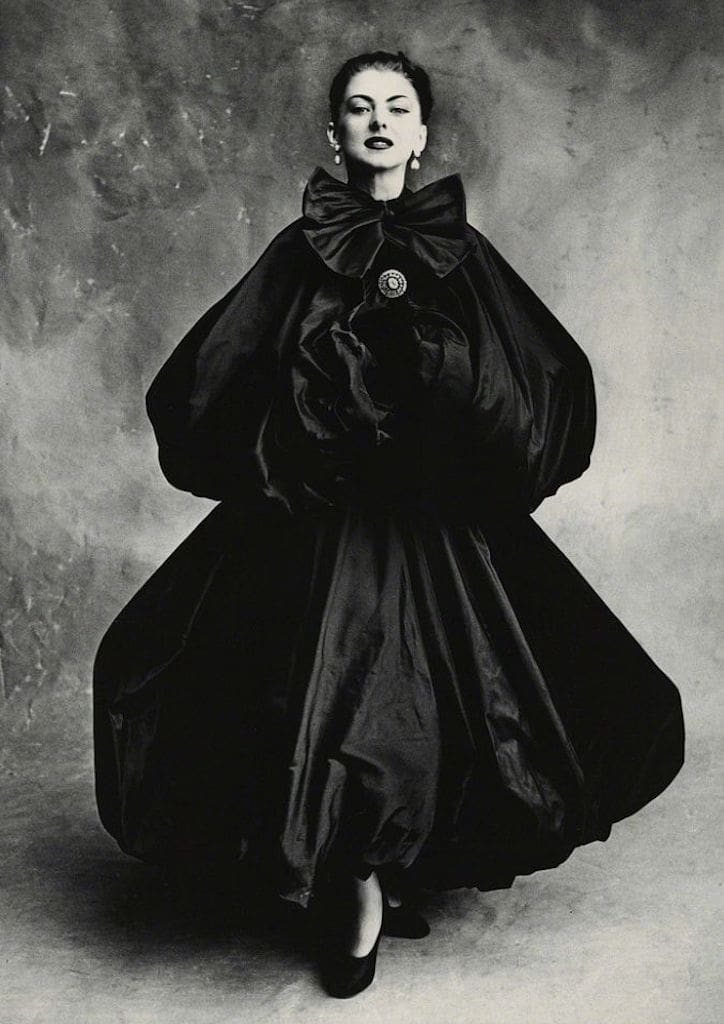

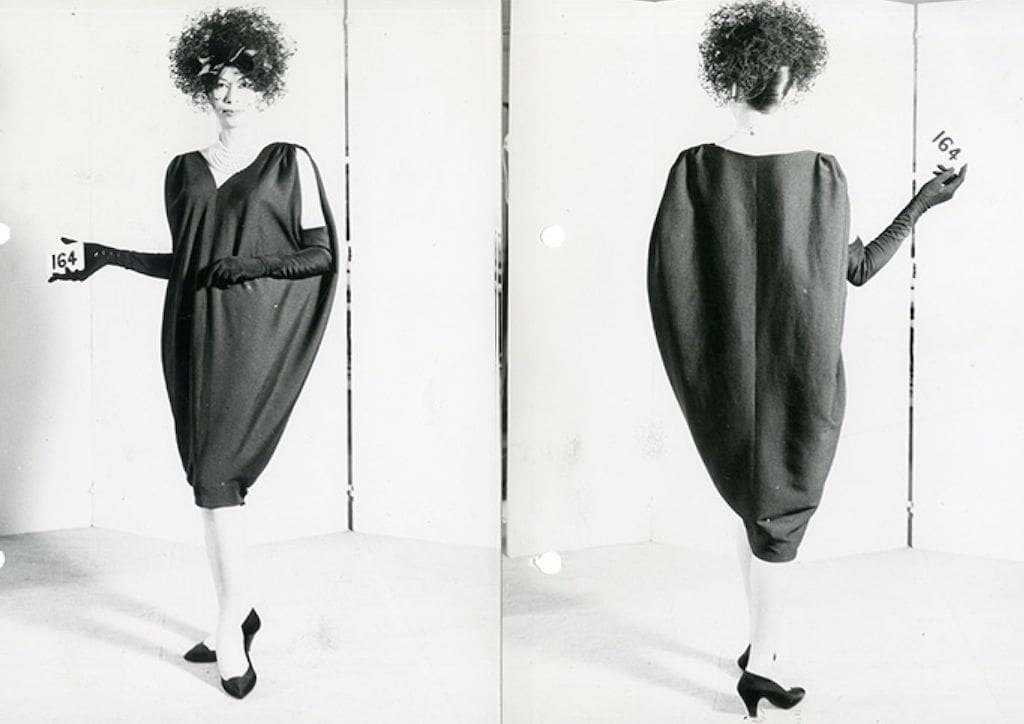

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Balenciaga was never really associated with a signature outfit. When one thinks of Coco Chanel, we immediately remember her effortless black slacks, tweed jackets, and long-strand pearls. Christian Dior is widely associated with the New Look of 1947, which launched the popularity of the tiny waists and full skirts of the 1950s. Balenciaga on the other hand, was keen on innovating. When clothes in the 1930s determined a regal grace, he preferred dark simplicity instead. In the 1950s, he changed women’s silhouettes by removing the waist and broadening the shoulders. This was a period in his life in which many fashion scholars consider truly began showing his true inventiveness and originality as a designer. In 1955 he invited the tunic dress, and in 1957, the balloon skirt. By the end of the decade he had created the Empire line, which included kimono coats and high-waisted dresses.

In the 1960s, Balenciaga conceived the radical sack dress, during a time when the popular look was still that of Christian Dior’s. With years of experience behind him, he began to step into the genre in which his fashion house would be most associated with, avant-garde structural designs. During this era, this was never before seen, and many were impressed that the Spanish designer was able to seamlessly translate his sketches into reality. Today, the brand is under the direction of Creative Director Demna Gvasalia. They are still watched closely for their radical moves in the industry that often make headlines around the world.

The Most Expensive Couturier in Paris

Many famous designers of the time studied or mentored under Balenciaga. Hubert de Givenchy, Oscar de la Renta, Paco Rabanne, and Pierre Cardin all worked studied under him at some point in time, before he closed his House in 1968, after 74 years of working. During his time, he rejected the idea of ready to wear collections. He stuck to couture, and did not like the idea of making something for somebody he did not know. He was picky about his clients and preferred his designs to dress only the sophisticated woman. This was well-portrayed in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread last year, with Reynolds Woodcock rejecting an American socialite from his service after she had made a drunken fool of herself on her wedding night.

Among his notable clients were Baroness Pauline de Rothschild, socialite and Harper’s Bazaar contributing editor Gloria Guinness, United States first lady Jackie Kennedy (the President was against the brand’s hefty price tag), Babe Paley (whose husband founded CBS), Mrs. William Randolph Hearst, and American Socialite Countless Mona von Bismarck, who was voted the Best Dressed Woman in the World during the 1930s. Bismarck only wore Balenciaga. When he died in 1972, she locked herself in her hotel room for three days to mourn. Balenciaga also dressed royals, including Fabiola de Mora y Aragon, whom he designed a wedding dress for her nuptials with King Baudouin I of Belgium. Hollywood stars such as Greta Garbo, Princess Grace of Monaco, Ava Gardner, Ingrid Bergman, Lauran Bacall, and Marlene Deitrich were also on his client’s list.

Owning one of his designs would often reflect on the women who wore them as being tastemakers of their time. They needed a considerable amount of wealth to be able to afford his bespoke creations. When the House was opened in Paris, he was known as the most expensive couturier in the market. For example, American heiress Barbara Hutton (who was referred to by the media as The Poor Little Rich Girl due to her troubled, personal life) was charged £5,376 for a gown she had ordered for a Beistegui 18th century ball in 1952. The gown was made of black velvet and had silver embroidery.

RELATED READS: Elizabeth Taylor and Her Legendary Addiction to Bulgari

Balenciaga’s Monsters

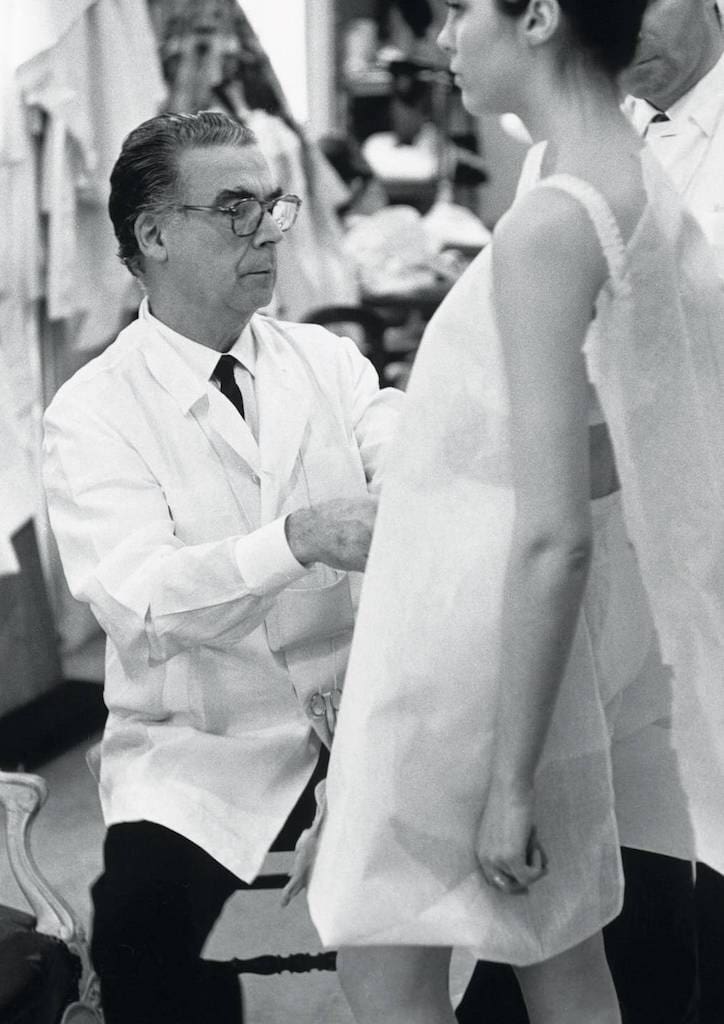

Throughout his career, all the way to his death, Balenciaga was always considered a reclusive man. He denied hype and only allowed one full interview in his lifetime. This was with Prudence Glyn, a writer for The Times in 1971, a year before his death. Glyn reported that Balenciaga said that he did not like explaining his train of thought to anybody. The House on Avenue George V was also said to have a rather strange atmosphere, dark and brooding from the outside, despite the incredible work done by Balenciaga and his team indoors. The buying experience consisted of at least three fittings in which Balenciaga would not attend (although he cut and sewed everything with his own hands). The house was run by Mlle Renée, the head directrice, who was often called the Mother Superior of Balenciaga. Hired in 1937, she kept the workers under close surveillance for the designer, making sure dresses were made and delivered on time. She sat on a desk near the doorway of the house, asking patrons for identification before entering, as if she were an immigration officer.

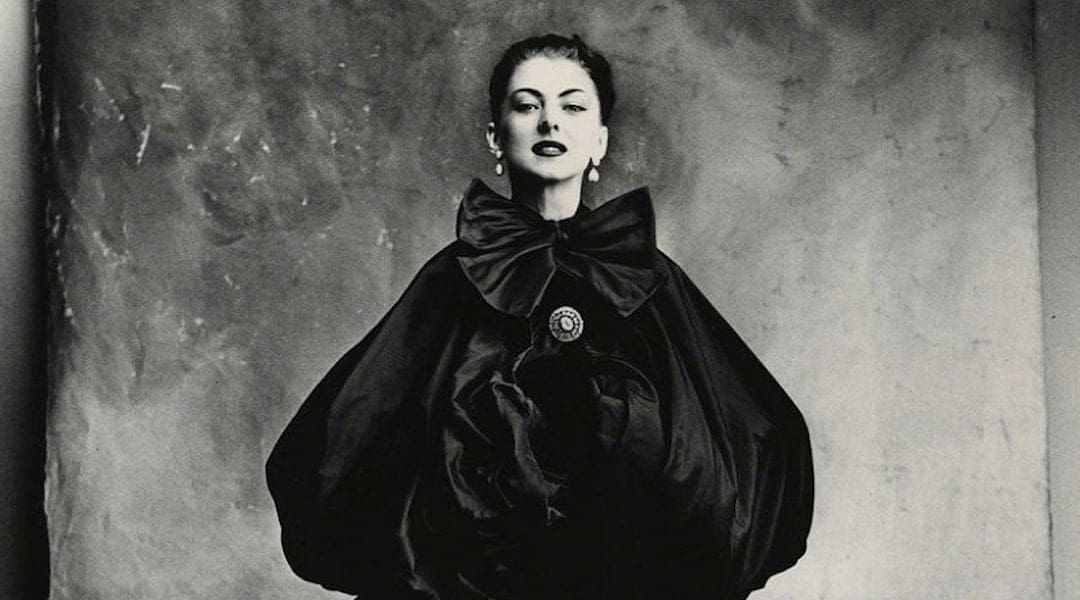

Apart from his team of creators, Balenciaga also had countless in-house models he liked to call “the monsters”. This was coined because of the way they were told to stride down the runway with empty faces and a Dracula walk. Models living in his house were under strict instructions on how they would walk and carry a Balenciaga creation. He favored models who had a little stomach, staying that it reflected the real woman that wore his clothes. To the dismay of fashion editors and photographers, Balenciaga was also the first designer who insisted that they only use his in-house models for photo shoots.

The Only True Couturier

Every season, houses would present their new collections to clients in private fashion shows. They would often run for one hour and include at least 200 new designs. Rumor had it that anticipation for Balenciaga’s collections were so high, that once, Audrey Hepburn was frothing in the mouth out of excitement. Continuing his antisocial behavior, the designer never attended the shows. He was often found backstage, peaking at the presentation via a hole in the curtains. Paul Thomas Anderson’s film portrayed the Balenciaga-esque Reynolds Woodcock in this situation as a nervous, ticking time bomb, who found solidarity backstage seeing that the models are dressed properly. He also never named any of his collections. Instead, “the monsters” would hold little number cards down the runway. If a patron was interested in buying the look, they would note it down on the provided notebook and submit it when the show concluded. These shows were often silent as well, with only the sound of rustling dresses filling the room.

Balenciaga was truly a genius of his time. Although stories of him often go back to his madness and lonesome nature, it’s what makes him such an icon. He is one of those 21st century artists that proved good work would take you far, rather than relying on PR and connections to get one somewhere. When he died in 1972, Women’s Wear Daily’s headline read “The King is Dead”, and a dark cloud was casted over the fashion world. The meticulous designer was beloved by both clientele and contemporaries alike. Coco Chanel puts it best, “He was the only true couturier, the others are just fashion designers.”