In a life saturated with clips, snippets, and summaries, finding the space to lose ourselves in art forms that take their time has become an enriching necessity.

Because this is an article about the dangers of our modern obsession with brevity, I’ll play with irony and get straight to the point: short-form content has always existed—but its ubiquity has now become a necessity, and it’s killing the most meaningful ways we engage with art, especially works that refuse to “fit” the mold of the snappy, hooky, and bite-sized.

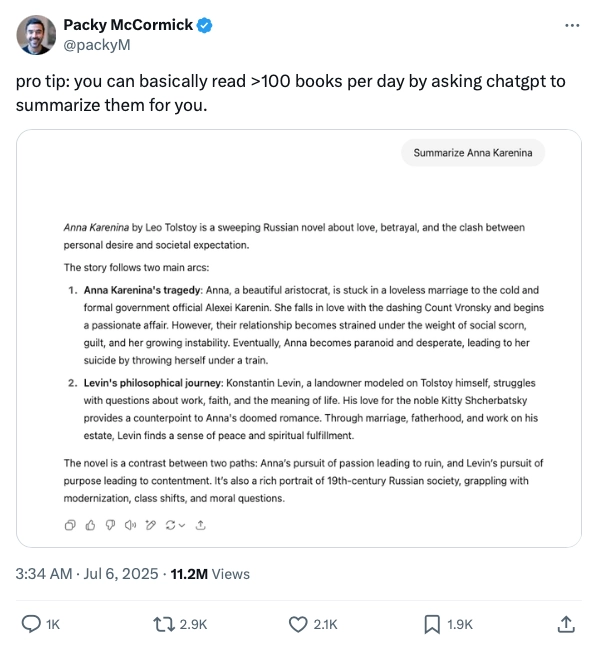

I recently stumbled upon a post on X by user Packy McCormick, who wrote: “Pro tip: you can basically read >100 books per day by asking ChatGPT to summarize them for you.” Attached was a screenshot of him prompting the large language model to summarize Leo Tolstoy’s gargantuan Anna Karenina. He didn’t stop there. In a follow-up post, he asked for a summary of The Lost Art of Reading: Why Books Matter in a Distracted Time by David L. Ulin. The mind-boggling irony made me hope it was satire, but the caption that followed proved otherwise: “This is incredible. On to the next one.”

We can’t police how people choose to interact with artistic works—this liberty, the open endedness of it all, is part and parcel of the act. So, if Mr. McCormick wants to ask a string of codes to regurgitate and spit out pieces of a larger whole, who am I to stop him? I can, however, question and examine the decision—because my main concern is how this mindset, more alarmingly prevalent than we think, ultimately affects how we approach the very details that lend art (and by extension, life, if we’re to be sentimental) its richness.

READ ALSO: Is The Internet We Knew Already Dead?

TL;DR! Just Give Me The Gist Of It

Too Long; Didn’t Read. TL;DR. It’s an acronym that’s ingrained into our everyday vocabulary, and while it was supposedly coined during the early 2000s, it turned out to be prophetic—an omen of the more streamlined world to come. I don’t need to overexplain the examples: we’re all aware of the constant demand to pare everything down to its bare essentials, “digestible” bits and pieces meant to be swiped through and glanced at during our busy daily rhythms.

There are entire YouTube channels dedicated to providing 10-minute film summaries. Short films are being reformatted vertically, optimized for mobile screens. Platforms like GoodShort churn out soap-operatic episodes under two minutes long. Even the Philippines’ own Viva Communications Inc. recently launched Viva Movie Box, which is set to deliver “Pinoy microdramas” for a nation on the go.

In an interview with the American Psychological Association, Dr. Gloria Mark—a chancellor’s professor of informatics at the University of California—reveals just how much the entertainment industry has adapted to this new age.

“I was very surprised to learn that TV and film shot lengths have decreased over the years. They started out much longer. They now average about four seconds a shot length. That’s on average,” she shares. “If you watch MTV music videos, they’re much shorter. They’re only a couple of seconds. So we’ve become accustomed to seeing very fast shot lengths when we look at TV and film.” And while Mark can’t say for sure if this is because filmmakers and editors are affected by their own decreasing attention spans, or they’re simply pandering to what they think audiences want, the fact remains that it’s a widespread phenomenon.

In publishing, book marketing has become a game of reducing entire novels down to tropes, genres, and simplified plot points: “Enemies to Lovers,” “Phantom of the Opera (But Set in Space),” “Horror with a Dash of Existential Dread.” And I get it—that’s the point of marketing. Forget the nitty-gritty; as long as it grabs attention and delivers exactly what readers might find enticing in half a second, it’s doing its job. After all, you’re competing with thousands of other messages, each crafted to be snappier, more tantalizing, and impossible to scroll past.

Yet, in doing this, you also risk misleading marketing: setting up readers for disappointment when expectations aren’t met, usually when they come face to face with the actual content and nuances of a book. It’s something sci-fi writer Ursula Le Guin warned us about in a 2012 opinion piece on the pitfalls of categorizing—and judging—entire works based solely on their genres.

“Some of these categories are descriptive, some are maintained largely as marketing devices,” she writes. “But then, how long will the publishers and booksellers last against the massive aggression of the enormous corporations that are now taking over every form of publication in absolute indifference to its content and quality so long as they can sell it as a commodity?”

It’s been a problem for a while, but it only seems to expand as the world adopts a more bite-sized approach to everything. Microfilms and trope-ified book pitches aren’t inherently bad: they have their place, especially since consumer habits won’t change overnight. But just because we’ve adapted to this way of life doesn’t mean it serves us.

Short Form, Shorter Attention Spans

And at the risk of sounding like a mother reminding you to eat your vegetables, I come bearing a few scientific findings about what short-form content is actually doing to our brains. If you’ve already heard this sermon before, feel free to skip ahead—but it’s worth revisiting the very real cognitive side effects that come with our digital diets.

One study found that heavy TikTok users had more difficulty resuming tasks after being interrupted or distracted by the app and its content—a process known as “context switching.” Other empirical studies reveal that students who spend more time consuming short-form videos tend to show lower attention spans and, consequently, poorer academic performance. While these studies come with their limitations, they all point toward a disturbing trend.

As for just how much attention we’ve collectively lost, we return to the findings of Dr. Gloria Mark, who’s been measuring attention spans since 2004. Using a stopwatch to track when people started and stopped individual tasks, she found that the average attention span then was two and a half minutes. Today, it has dropped to just 40 to 47 seconds—coincidentally about the same length as your average TikTok video, as journalist Adam Clark Estes once pointed out in Vox.

This shrinking attention span ultimately takes more than it gives. Mark’s research shows a clear correlation between the frequency of “attention switching” and stress. Put simply, the faster we jump from one thing to another, the higher our stress levels: a pattern that has been confirmed by data from her research participants’ heart rate monitors.

We’re seeing the cultural aftershocks of this phenomenon, too. In the U.S., the number of adults who read for pleasure has fallen by nearly 40% from 2003 to 2023. The Philippines, which has always struggled with low literacy rates, tells a similar story. As scholar Ambeth Ocampo notes in an opinion piece, a National Book Development Board (NBDB) survey found that while 80% of Filipinos read non-school books in 2017, that figure had dropped to just 42% by 2023.

In her guest essay for The New York Times, writer Mary Harrington argues that long-form literacy has evolved into a “luxury good,” reserved for those with the time, focus, and extra resources to sustain deep reading. This transformation, she suggests, mirrors the broader consequences of a digital culture, which privileges speed and convenience over depth. Just as cheap, addictive junk food crowds out nutritious meals, the constant influx of short-form digital content leaves our minds overfed yet undernourished.

It’s easy to dismiss all of this as alarmist noise. Here comes another writer, another saccharine person in the creative field, lamenting the effects of modern life. But the reason I write this—the reason I’m intent on holding onto whatever attention I have left—is because I want to reclaim and preserve it. I’ll admit, I’m not immune. My focus has thinned, especially with long-form works. Films, I can still manage; two hours feels like a reasonable investment with a clear reward at the end. But television series? The commitment feels heavier. Biblically thick books that I would easily devour in three days back in high school now seem daunting. Part of it, of course, is the busyness of adult life, but I can’t deny that something in my brain has changed.

When Short Form Takes Over, It’s Time To Bring Back The Old Adage

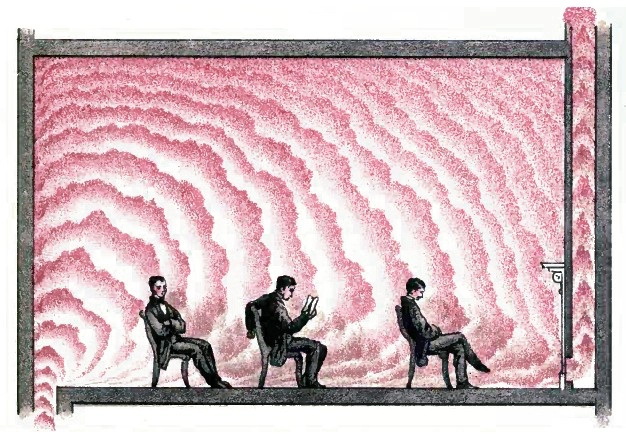

Short form content has made it more difficult to engage with anything that doesn’t offer an immediate dopamine hit of instant gratification—which means we have less and less patience to withstand material that challenges us, that asks us to grapple with complexity and savor the intricacies of human creativity.

There’s the old adage that’s been overused to the point of asphyxiation, but I’ll say it anyway: it’s the journey. Yes, a good story must have that final pay-off or well-earned ending. But what about the in-between? The odyssey of color, light, and layers of unspoken artistry someone leaves in every film frame or canvas. The textures of language (as I write this, know that I’m thinking about the placement of every word, how it changes tone and flow), the minutiae of emotions and experiences you can only understand if you took the time to feel them, to sit with a work in its entirety.

Just try this. Just try to remember a favorite book, film, TV series, or even a song. Something you absolutely adore. Something that made you cry or laugh or think. Cut it up. Remove everything until you’re left with 47 seconds worth of it. Would it really mean anything at all?

I’ll use one of my favorite books as an example: Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles. I asked ChatGPT to summarize it in a sentence: “The Song of Achilles is a retelling of the Greek myth of Achilles through the eyes of his companion Patroclus, exploring their deep bond, love, and tragic fate against the backdrop of the Trojan War.” But what that line will never give me, unless I decide to actually read the book, is the way Miller writes about devotion shared between two people. The familiarity. The etching of one life onto another. “I could recognize him by touch alone, by smell; I would know him blind, by the way his breaths came and his feet struck the earth. I would know him in death, at the end of the world,” Patroclus thinks about Achilles. How could a sentence ever capture the feeling of reading this, of reaching this point in the narrative, for the first time?

And this doesn’t just apply to what we consider as “high art” or “cerebral” work. I, and no doubt many other fans, didn’t watch (and rewatch, a sickening number of times) Princess Diaries 2 with the sole intention of finding out whether Princess Amelia Mignonette Thermopolis Renaldi (Anne Hathaway) ends up with the dashing Nicholas Devereaux (Chris Pine). No. I watch it to relish in Shonda Rhimes’s humorously offbeat, definitely imperfect, but nevertheless delicious screenplay, which simmers with the chemistry that Pine and Hathaway bring to the table. I wouldn’t trade the experience of its hour and 53-minute runtime for a billion dollars—it has nourished my soul in ways that transcend words.

I can’t speak for a lot of other creatives, but as a writer, I know for certain that I don’t practice the craft just for the sake of delivering a message; otherwise, I’d just use bullet points. Never mind if you forget the gist of what this article is even about. If you sat through this, then I’ve already achieved what I hoped for: a moment of understanding shared between us, whether or not you agree with my perspective. You stayed. You chose to experience the wholeness of my thought.

So to answer the title of this article, lingering doesn’t “pay,” really. It offers nothing but the sheer pleasure and enrichment of the act itself; but in this landscape of endless scrolls and summaries, that act of patient immersion is worth everything.