Decades since its premiere, audiences both new and old still think about the ways in which Wong Kar Wai’s classic deftly explores the complexities of the unspoken.

Warning: This piece explores certain elements of In the Mood for Love that may contain spoilers for those who’ve never viewed it.

Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love was Hong Kong’s official selection for Best Foreign Language Film during the 73rd Academy Awards in 2001—but it would never be nominated. For fans of the work, the natural instinct is to say “what a shame,” but really, we all know it ultimately didn’t matter: the film would manage to cement its place in cinema history, and the hearts of many, with or without its accolades.

It continues to dominate the top spots of “Best Films” lists, including fourth place in The New York Times’s recent “The 100 Best Movies of the 21st Century.” In 2020, it got a 4K restoration with the help of the Criterion Collection and L’Immagine Ritrovata. This 2025, it celebrates its 25th anniversary with theatrical re-releases of the 4K restoration all around the world (in China, it includes a nine-minute post-film bonus short, “In the Mood for Love 2001,” which Wong Kar Wai describes as “not an epilogue exactly, more like a letter I wrote 25 years ago–finally delivered.”)

Whether audiences are watching the film for the first or umpteenth time, the fact of the matter is it’s just as captivating as it was when it first premiered. Why? Well, everyone has their reasons for loving something. But as an anniversary tribute, let’s explore the ones that—at least to this writer—make it unforgettable.

Finding Yourself In The Mood For Love

The movie’s premise is deceptively simple: two neighbors find out their respective spouses are having an affair. It’s what this infidelity incites that serves as the emotional core of the film; it’s a slow, inexorable unraveling of the gut-wrenching, ugly truth.

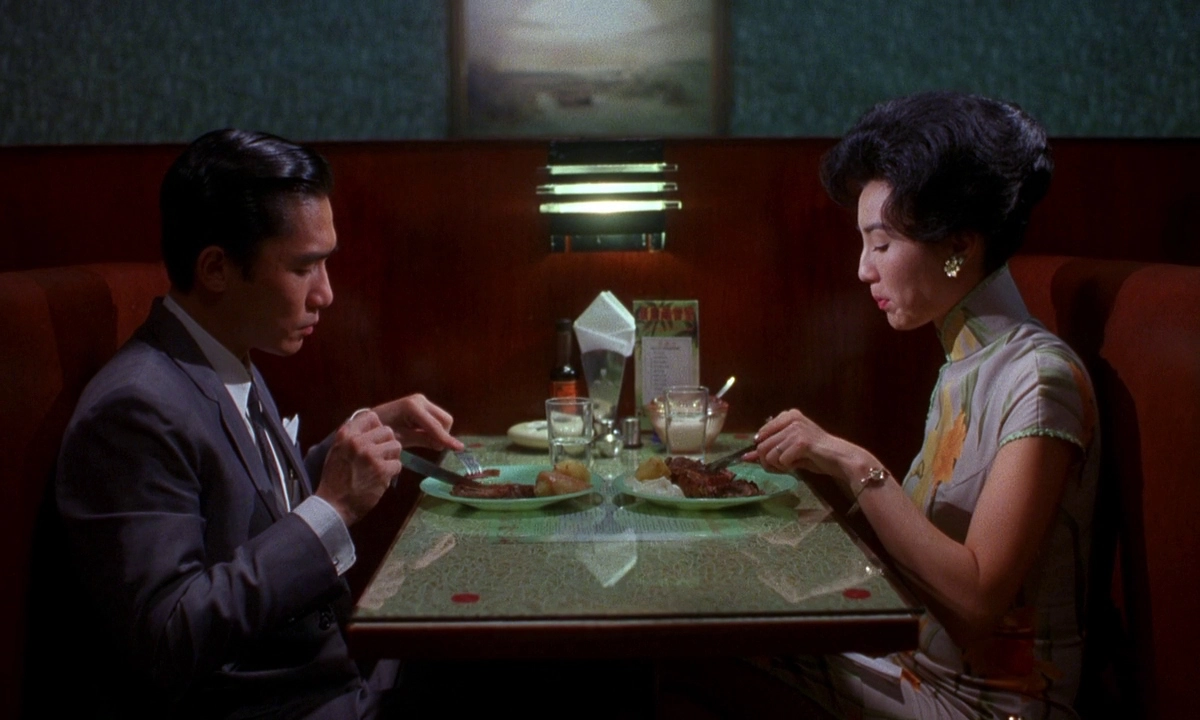

This plot wouldn’t have worked as effectively without the nuanced acting of Maggie Cheung (who plays Su Li-zhen, a woman who works as a secretary in a shipping company) and Tony Leung Chiu Wai (who takes on the role of journalist Chow Mo-wan).

The two performers carry a plethora of emotions in a single glance or gesture, something necessary in scenes where words fail—as they so often do when it comes to love. Even before they utter their lines, you can sense the unease, the quiet unhappiness and abandonment that lingers like a brewing storm as their spouses often leave them to spend evenings alone.

Appreciating this film is an act of patience and observation. See the way Su prepares a meal for Chow when he’s sick, or how the man lets her in on his dream of writing a martial arts serial. In fact, the entirety of the movie relies on subtlety: blink and you’ll miss it. A tie, a matching handbag, a series of phone calls, even a one-liner about work—nothing is inconsequential to the story’s build-up.

Simple camera movements add to this, allowing viewers to soak in all the details. This also makes the sudden, quicker shots more apparent during pivotal moments, heightening charged exchanges.

READ ALSO: Jaws At 50: The Story Behind Steven Spielberg’s Landmark Masterpiece

A Dreamy Montage Of Warmth, Suffocation, And Isolation

One of the most defining features of In the Mood for Love is its cinematography, thanks to the work of Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bing. It depicts the urban grit of 1960s British Hong Kong while still maintaining a sense of hazy, dreamlike romanticism. Its predominantly warm hues of red, orange, and yellow are practically burned into my retinas at this point, so distinct that it started an entire aesthetic wave during the 2000s, inspiring filmmakers like Barry Jenkins and Sofia Coppola.

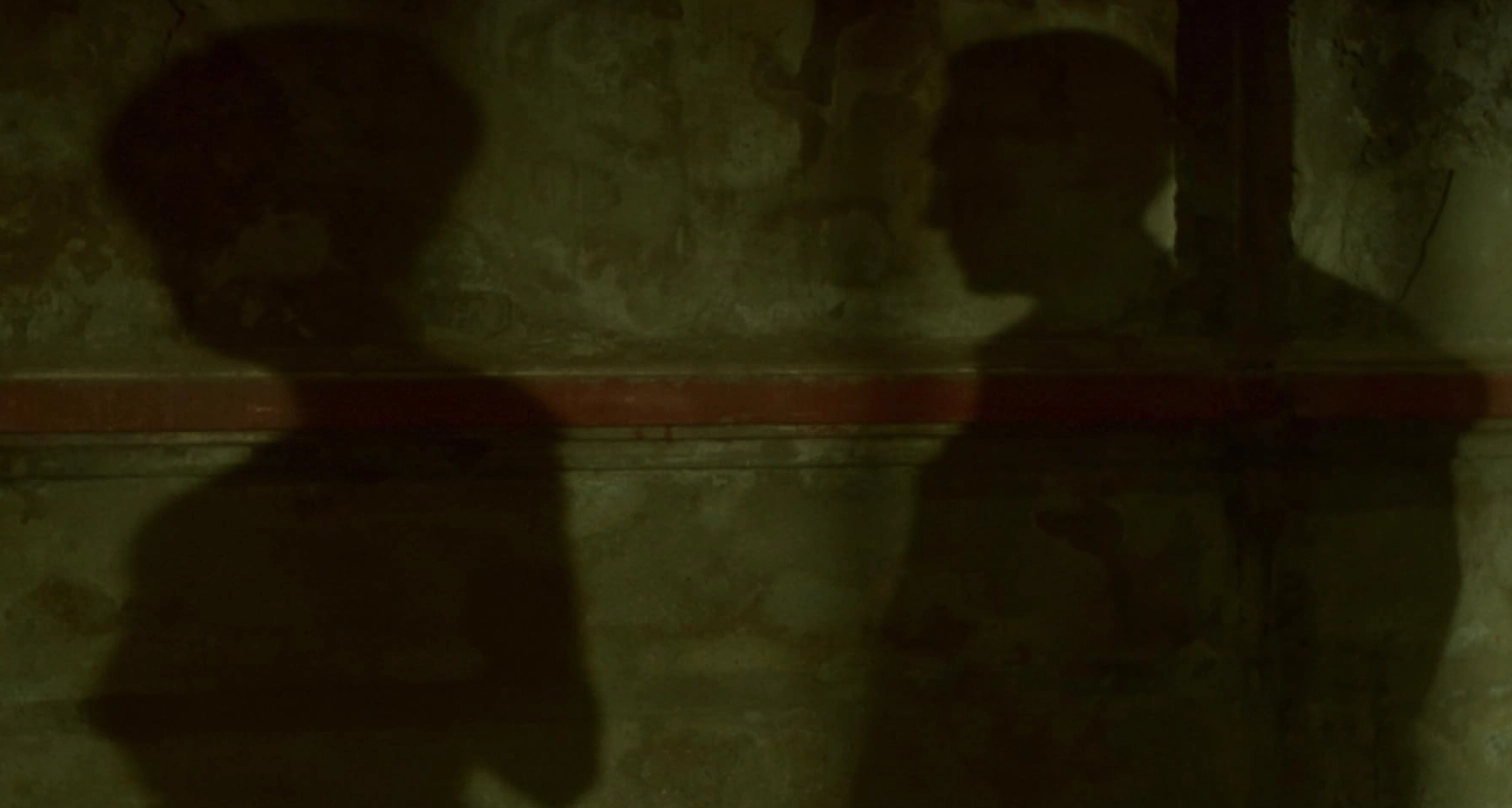

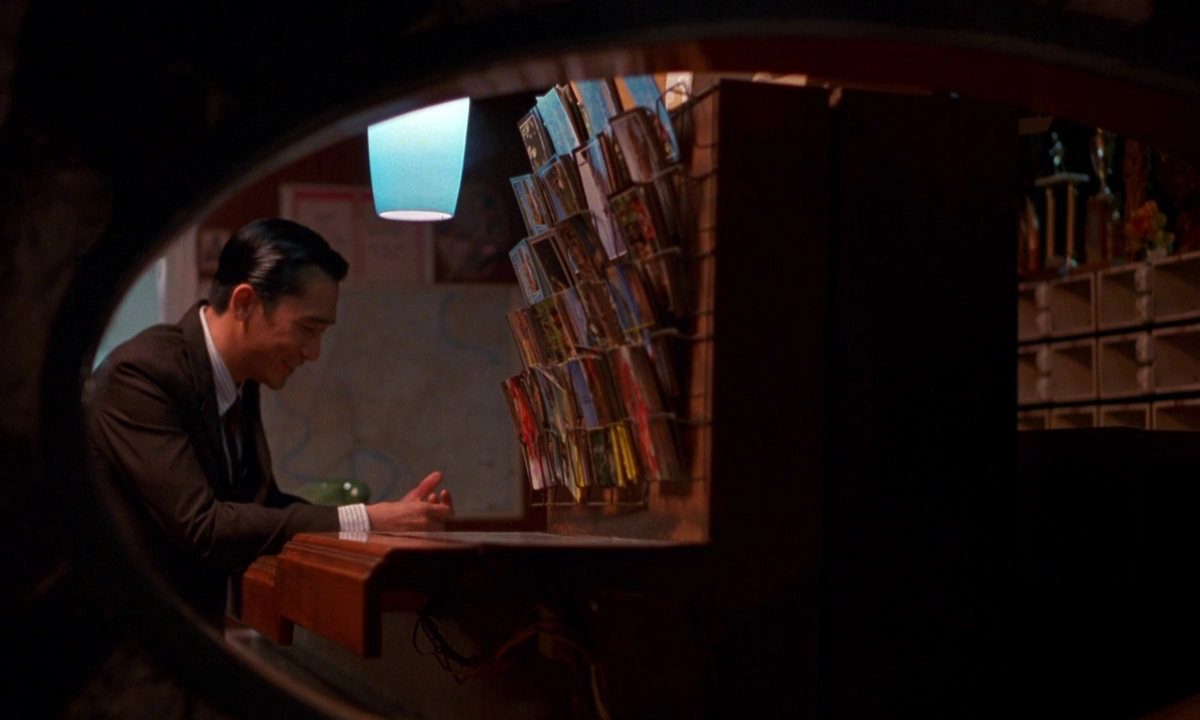

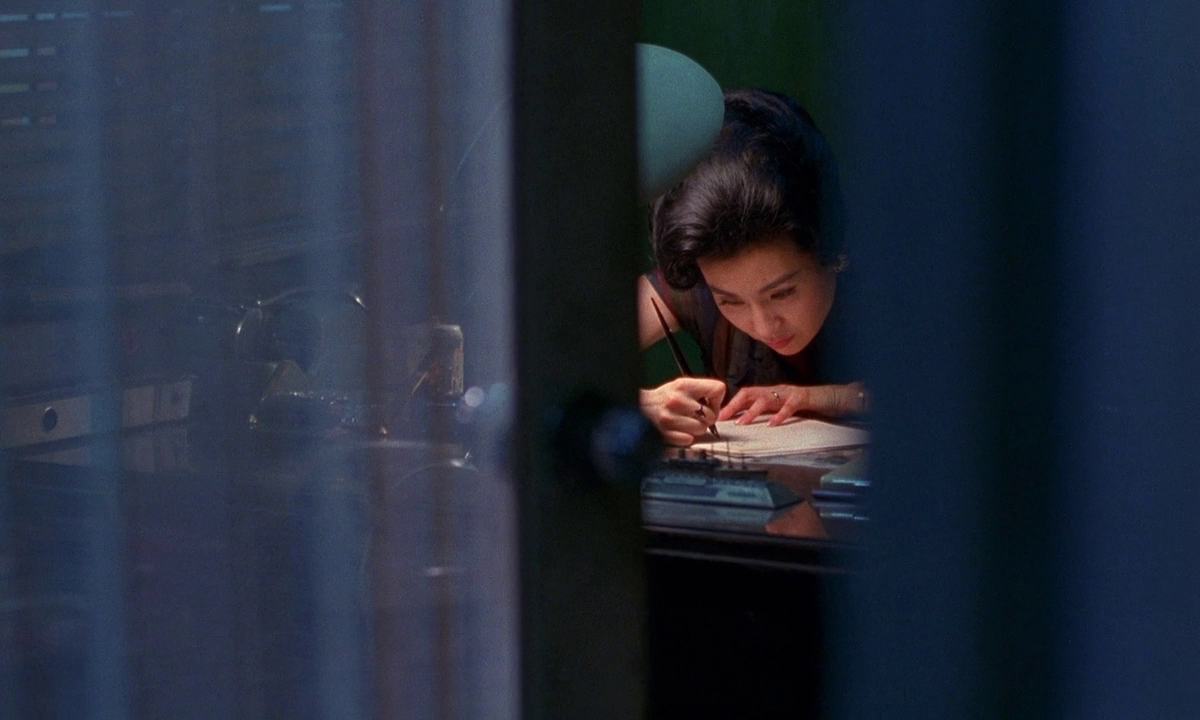

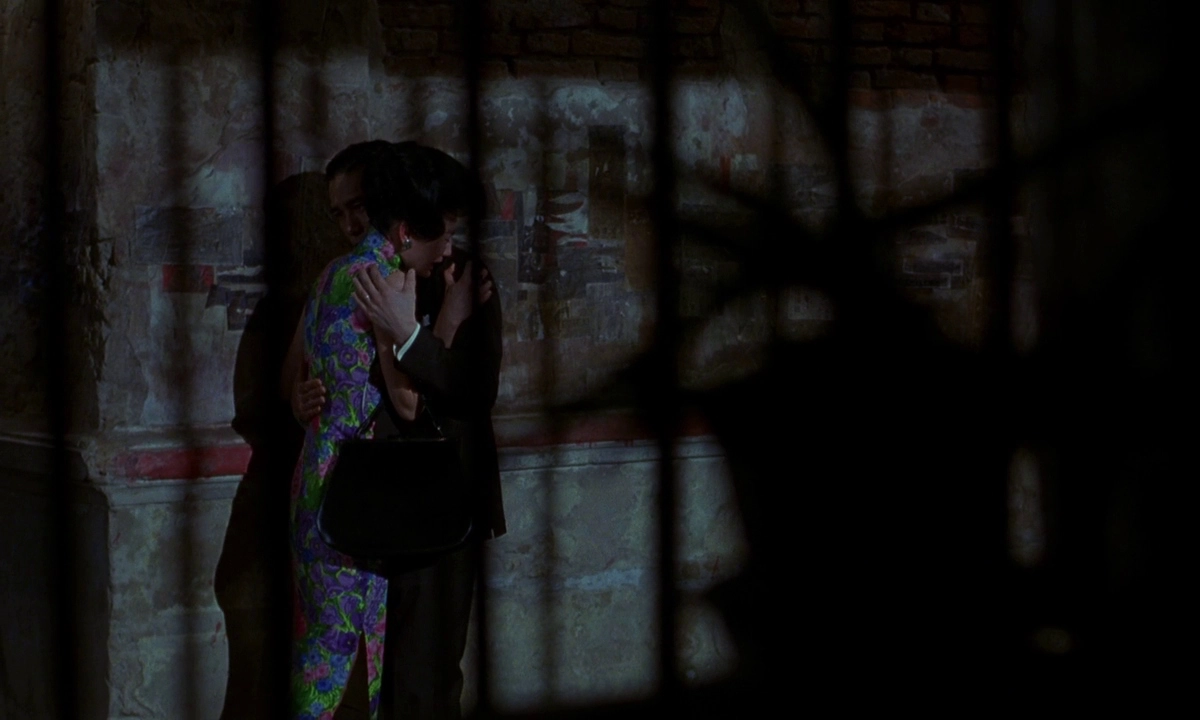

Color isn’t the only visually striking thing about the film. Its shot compositions are phenomenal, essential parts of the storytelling. Characters are framed by the structures surrounding them—be it walls, doors, narrow stairways, windows, or mirrors—creating claustrophobia-inducing imagery that reflects the suffocating, repressed emotions haunting every scene. Even when the spaces aren’t small, characters are framed in a way that isolates them from the environment, creating a vast sense of loneliness.

Su and Chow’s unfaithful spouses are specters: either cut out of the frame or shown with their faces obscured. In both a tangible and figurative sense, they become nothing but disembodied voices moving farther away until they disappear from the picture entirely. Suddenly, it’s not about the affair anymore—it’s about whatever happens in the star-crossed aftermath.

When Costumes Are Character And Sound Is Story

In the Mood for Love had to succeed on all fronts to be considered the masterpiece it is, which is why its costumes and sound design also deserve praise.

Costume is character with the work of designer William Chang. Who is Chow—that struggling, tired writer meant to evoke a sense of somber and enigmatic suaveness—without his tucked-in dress shirts, ornate ties, and slicked back hair. Even his cigarettes become a part of who he is (and a marker of a Wong Kar Wai piece), their viscous wisps of smoke choking each frame they’re in.

Su’s iconic cheongsam dresses, so tight-fitting that they limit the breadth of her movement, feel at once elegant and sensual. Even the restrictiveness of her clothing is a nod to the air of rigidity and tradition she tries to maintain, expectations set upon women during her time. This glamorous appearance is also a facade Su carefully puts together even in quotidian scenarios like buying noodles or watching movies. It’s her way of masking the dread and sadness she feels—and perhaps the only form of consistency in her upended life. Cheongsam colors and patterns signal who she is at a given time, changing to match her mood and surroundings, then later on, to complement Chow’s own outfits, showcasing their burgeoning connection.

And who can forget the sounds of the film: namely that recognizably heady, melancholic, and string-forward piece “Yumeji’s Theme” by Shigeru Umebayashi, which serves as a leitmotif for Su and Chow’s interactions, the backdrop of their fateful encounters. “Quizás, quizás, quizás” sang by Nat King Cole plays somewhere in the background too: repeating the Spanish statement “perhaps, perhaps, perhaps” to signal the emotional uncertainties Su and Chow can’t confront, and the hypotheticals they impose upon themselves.

How “In The Mood For Love” Finds Meaning In What’s Left Unsaid

The movie’s exploration of the unspoken—which perfectly captures the tension between desire, personal principles, and societal norms—is why it remains so relevant and deeply human.

At some point, in an almost masochistic manner, Su and Chow reenact the ways they think the affair began, trapping themselves in a loop of pain. Yet the more time they spend together, the harder it is to deny their mutual attraction. Eventually, it’s difficult to distinguish what’s real and what’s pretend: a graze of the hand, a hug, a vulnerable confession. Even Su finds herself caught off guard, frequently crying in Chow’s arms, unable to withstand the emotional toll of it all.

“What fascinated me wasn’t the betrayal itself so much as the reenactments: like both sides of a coin, the pair who were betrayed playing betrayers, dissecting infidelity like a crime,” Wong Kar Wai shares with the British Film Institute in a special interview for the movie’s 25th anniversary.

It might seem strange to dig your finger into a wound, but these nightly dramatizations illustrate the natural and desperate need to make sense of chaos, to find the rationale in irrationality. Or, as writer Joan Didion describes in her book The Year of Magical Thinking: “Confronted with sudden disaster we all focus on how unremarkable the circumstances were in which the unthinkable occurred.”

“I wonder how it began,” Su says one night as they walk home from the noodle stall they both frequent.

“It’s already happened. It doesn’t matter who made the first move,” Chow later responds.

The two continue to circle one another throughout the movie, Su withdrawing to avoid gossip and hide from the intensity of her feelings, Chow becoming increasingly unable to do so. In refusing to name desire, the two characters attempt to erase its existence; but the movie itself hides nothing, stripping everything bare until they can no longer ignore the glaring truth.

“I was only curious to know how it started. Now I know. Feelings can creep up like that. I thought I was in control,” Chow confesses.

It’s an ironically tragic situation. Two people think themselves immune to the unpredictability of love, hoping their sense of duty and morals will shield them—instead, they find the answers they desperately seek by experiencing them in full force.

“’For us to do the same thing,’ they agree, ‘would mean we are no better than they are.’ The key word there is ‘agree.’ The fact is, they do not agree,” writes critic Roger Ebert in his 2001 review of the film. “It is simply that neither one has the courage to disagree, and time is passing. He wants to sleep with her and she wants to sleep with him, but they are both bound by the moral stand that each believes the other has taken.”

“It is a restless moment. She has kept her head lower to give him a chance to come closer. But he could not, for lack of courage. She turns and walks away.”

The Passage Of Time And The Release

They say that in any good story, characters get what they need, rather than what they want. In the Mood for Love wouldn’t be what it is without the heartbreak that thrusts its plot forward. Chief among its quiet tragedies is seeing two people who are so painfully compatible—both in disposition and shared struggles—and somehow knowing that it’s never going to work out, even when the movie makes you think it will for a few breathless moments.

The passage of time plays an important role throughout the film: it’s the ebb and flow of emotion, the intermingling of two lives, and the dissolution of memory. Scenes are fragmentary, fading to black, jumping from one indiscernible season to the next, looping and playing in slow motion, leaving viewers unsure of exactly how much time has passed—only a few slides sprinkled at the beginning and end indicate what year it is.

By the end of it, Su and Chow part, never to encounter each other again. They come close, but there’s always some distance in the form of missed opportunities. All they have left are the memories, and the unspoken sentiments they carry with them. Years later, Chow is alone in Singapore, and Su returns to her old apartment, embracing it as a remnant of the love that both broke and nourished her during a tumultuous period of her life.

“If someone had a secret they didn’t want to share, you know what they did?” Chow tells a friend over a meal. “They went up a mountain, found a tree, carved a hole in it, and whispered the secret into the hole. Then they covered it with mud. And leave the secret there forever.”

Time passes once more, and then comes the final scene I wish I could experience for the first time again: Chow finding a hole on a stony temple wall in Angkor Wat, Cambodia, and leaning in to whisper into it. A lone monk serves as his only witness onscreen; offscreen, the viewer is pulled into this clandestine ritual. He leaves the hole covered with a clump of mud and grass. Does he want to say goodbye or preserve something precious? We’ll never really know, though we’ll certainly carry that moment with us long after the credits roll.

“He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.“