Everything dies, but pets—living only a fraction of our lives—have us saying goodbye, again and again. So why do we still choose the inevitable pain?

Content Warning: This article contains mentions of pet illness and death.

A quote from C.S. Lewis that always resurfaces whenever I think about the kind of pain that loving a pet inevitably demands—or already demands. “There is no safe investment. To love at all is to be vulnerable,” he writes in The Four Loves. “Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal.”

It’s true. We can hide behind our walls and distractions, build shells to keep ourselves safe—and yet, we don’t. We choose the harder path when we choose to live with pets. We know the lifetimes of most domesticated animals will only ever be a fraction of ours, and still we take them in. We set aside the knowledge that it will all end sooner than we’d like for the chance to care for something other than ourselves.

We try not to think about deterioration. The way time passes is quicker than we thought possible. We crave stasis, play mental games, insisting our dogs are still puppies, our cats still kittens. If we believe hard enough, maybe we can stall the eventualities, even erase them—and on most days, we wish we could.

But it always ends the same way: you lose them within your lifetime. If you live with multiple pets or have had one in every season of your life, this becomes a cycle of goodbyes, and it hurts every time. There’s no easy way out. It feels almost masochistic. Why would anyone run themselves through the heartbreak machine? Do we never learn? Why do we insist on attaching ourselves to loves we can never keep?

Well, if I knew all the answers, I wouldn’t be here writing this. I wouldn’t have pitched this feature to my editors, knowing full well I’d end up crying at some ungodly hour, thinking about why we choose to pay the steep price of loving a pet, and still not finding a definitive answer. I can try, however, to give an honest one.

READ ALSO: In Defense Of The Romanticized Life

It Feels Like I’ve Known You Forever

Let’s paint some vignettes. This is a tale you know quite well. You’re in it. I’m in it. It’s a mirror, as much as it’s an elegy.

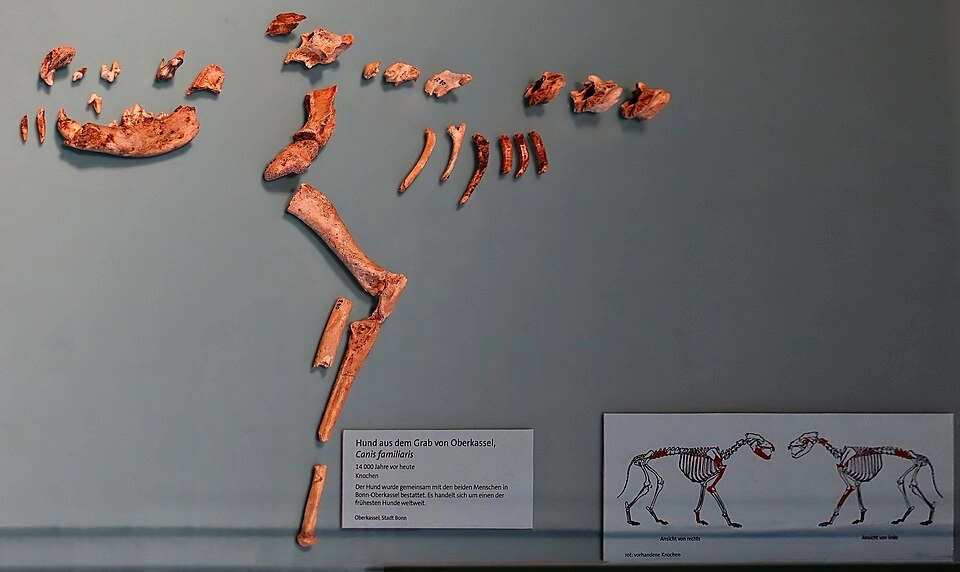

In 2018, the remains of a 14,000-year-old canine showcased one of the earliest examples of dog domestication and bonding. They called it the Bonn-Oberkassel dog, a puppy living among pre-Holocene hunter-gatherers. Remember this, it’s important.

Our domestication of wolves seems purely utilitarian. We feed you, you protect us. Easy. Transactional. But this puppy, which scientists suspect might’ve suffered from canine distemper infection (morbillivirus)—marking a long and painful illness between 19 and 23 weeks old—was useless. Absolutely, utterly useless. Likely twisting in pain, feverish, dehydrated, lethargic, expelling diarrhea and vomiting. The most resource-efficient thing to do in this situation is to let nature run its course.

So how did the pup survive long enough to outlast a disease with such a high mortality rate?

Because someone, maybe several someones, chose to nurse it through those bouts. Not once, not twice, but as many times as it took. Someone kept it warm and clean. In a world where pausing could mean death, that gesture speaks volumes.

Archaeologists unearthed the graves of more than 600 cats and dogs in ancient Egypt, one of the oldest pet cemeteries ever found. The animals were “laid gently in well-prepared pits,” wrapped in textiles or placed inside pottery like miniature sarcophagi. 90% were cats, many still wearing collars or necklaces of iron, embellished with glass or shells. Someone took the time to do all this.

In ancient Greece and Rome, owners were creating epitaphs for their pets.

“I am in tears, while carrying you to your last rest place as much as I rejoiced when bringing you home in my own hands fifteen years ago,” a person writes.

“[Myia] never barked without reason, but now he is silent,” one expresses.

Yet another epitaph: “My eyes were wet with tears, our dear little dog, when I bore thee [to the grave], a service which I should have rendered thee with less grief three lustrums ago. So, Patricus, never again shalt thou give me a thousand kisses. Never again canst thou lie contentedly in my lap.”

It’s strange that centuries later, the words still reach out, as if to say: we have always chosen to love, despite knowing how it ends. Remember this, it’s important.

A high school friend once had a rabbit she adored. She scraped together her savings for toys, enclosures, and treats. She sent videos and photos that, if stitched together, could probably stretch the length of this entire country. The rabbit got sick. She did everything she could, but it passed away anyway. I’d never seen her so distraught. She cremated the bunny like something sacred and kept its ashes in a small metal pendant.

A family friend, a towering doctor with the stature of a man who could hold up the sky if he chose to, was reduced to tears when their Mini Pinscher died. His wife described the scene: the imposing man kneeling, shoulders shaking, body heaving as he cradled the tiny creature in his arms, shirt soaked in tears.

To me, such situations resemble a tiny pin dropping onto a city and somehow leveling it completely. But how does this happen?

Tell Me Why It Hurts

Grieving a pet is complicated. It’s at once earth-shatteringly legitimate and, at least from an outsider’s view, illegitimate. Let me explain.

The thing about loving an animal is that it’s ridiculously simple. Maybe that’s why we grow so attached, and why their absence destroys us more than we can ever prepare for. In an essay for The Atlantic, Tommy Tomlinson describes the situation immaculately; though he writes it from the perspective of a dog owner, his ideas can be applied to most pets. The article’s subhead is a jarring revelation: “I loved my mom more than my dog. So why did I cry for him but not for her?” Hear him out.

“Dogs, especially, live to please us. It is the way they have made themselves essential to our lives. Dogs don’t fight at the dinner table or have obnoxious political viewpoints. They don’t slam the door when they leave the house. They don’t ask why you’re not married yet,” he writes. “When we mourn a dog, we mourn a life we often witnessed in full, and a source of something close to an unadulterated good. When we mourn a human, even one we love deeply, our emotions are messier. That does not make our grief lesser. It just makes it part of a bigger experience, like an egg mixed into batter. At some point, you can no longer separate it out.”

There’s nothing to detangle. Suddenly, this source of pure light disappears, sucked into a void, the rug pulled out from under you. It’s why studies show that owners experience the same level of grief over a pet’s death as they do a human’s, including a family member.

Yet it’s difficult for those who dislike pets, or those who’ve never owned one, to really empathize. It’s not their fault—it’s simply something that must be experienced to be understood. Phrases like “But it’s an animal” or “Just get a new one” still make an appearance. Consider this: people are more likely to excuse you for spending a month grieving the death of a grandparent than they would, let’s say, that of a beloved dog.

They won’t say it explicitly, but it’ll be implied; mourning an animal, at least publicly (you can keep the ugliness behind closed doors), has an invisible expiry date. There’s an unspoken rule that expects you to “recover” faster from a pet’s death than a human’s.

When this happens, people tend to go through “disenfranchised grief,” a situation where a loss is “unacknowledged” and the bereaved can’t properly express their sentiments, as Breeanna Spain, Lisel O’Dwyer, and Stephen Moston explain in a paper on the topic. This, in itself, hurts. It compounds the sadness, pressing on a raw wound. You feel more alone than ever. Personal loss is already an isolating, myopic lens that sees your grief as unprecedented—what more when people can’t seem to understand why your pet mattered so much?

Dog Days

I’m fluent in the language of goodbyes. For as long as I can remember, we’ve always had at least one dog in the house. Our first Labrador, whom my mother calls her first child, would eat cookies out of my pudgy toddler hands while watching me on lazy afternoons. I can’t remember him, but my parents say he loved me. When someone poisoned him while they were away on a trip, my mother was inconsolable for more than a year. The portrait she painted of him, his face somber and noble, still hangs in her room.

Then came our English bulldog, who saw me grow from toddler to child: stinky, wrinkly, slobbery, sweet, and clumsy. But bulldogs only live about eight years; it was a brief friendship. Bone cancer got to him, spreading too fast to stop. His howls of anguish tore through the house each night until my parents finally did the most humane thing they could—but humane never means easy.

Our Pekingese, the companion I wished for in lonely grade-school years, was a bit of an ass to everyone except me and my mother (he carried a special hatred for my father). Still, I loved him, difficult as he was. An immunodeficiency sickness took him at the age of nine.

Within that time, there were two others. Another Labrador, rambunctious and fond of leaping into the fountains along High Street, was both a source of embarrassment and laughter. He died of leptospirosis, suddenly and fast, gone by morning. I remember waking up and wailing like a wounded animal myself. Then a golden retriever who came to us late in life. She belonged to a family friend whose children developed severe allergies. Passed from one household to another, she finally found her home with us. Gentle and startlingly intelligent, she helped my sister overcome her fear of dogs. She taught me what it meant to love a creature that’s seen better days.

Years later, uterine cancer took her. I remember lying in bed with a fever the day my mom brought her to be put to sleep, unable to go along, crying until it felt like I was burning a hole through my face. Why, I thought. Why her? She’s a good girl. Good girls shouldn’t die—but if owners had a say, our pets would live forever. We buried her with her favorite tennis ball in my uncle’s garden in Pampanga, next to all our other dogs. There’s a banana tree there now; its fruits are so sweet I shed tears while eating them.

They say there’s always that one dog who changes you irrevocably. I’ve loved all our pets, but my Jack Russell is that dog for me. He wasn’t easy as a puppy—wild, stubborn, hair-yanking, he was destruction incarnate. Once, he bit me by accident during a fight with another dog. It left a deep scar, though even that eventually faded. Nine years later, he still gets himself into trouble, but I love him the way I’ve never loved anyone or anything, not even myself. And I know he feels the same. He hates it when I leave. He follows me everywhere. When I’m away, he waits by my door, hobbles to the gate every night, ears perked for the sound of my steps.

“That dog really loves you,” my dad says. I know. I know.

A few years ago, he was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer: hemangiosarcoma. He underwent surgery to remove a life-threatening tumor. It was successful, and with maintenance medicine, the vet said he might still live a long life. But the threat looms each time I sit in a fluorescent clinic, waiting.

The day of his surgery, the vet walked me through every possibility—including the one where he wouldn’t come back. That night, I lay in bed crying until my skull felt hollowed out. My mother lay beside me, crying too.

“I don’t want my heart anymore,” I told her. “I’m so tired. I feel too much. Why is it so hard to love another living thing?”

She said it never gets easier. I know. I know.

Two years later, I count each month like a miracle. I hold my breath. I walk my dog. I bathe him. I kiss and hug him. I persist knowing that one day, it’ll stop—that I’ll burn that hole through my face again. That a part of me will die a little, again, will lay beneath the soil of that banana tree. But for both our sakes, I choose the side of the living, until the day comes when I can no longer do so.

In 2024, we adopted another senior dog. Her owner, an elderly woman, had passed away suddenly. I know this little one will go too, one day. When you take in a senior dog, it’s no longer about how much time you have left with them—it’s about how much time you have left to make them feel like the most loved dog in the world. And that’s the easiest part, because being with you is all they need for that to be true.

What Is Real Loss?

Here’s how the rest of that C.S. Lewis quote goes: “Wrap it [your heart] carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket–safe, dark, motionless, airless–it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable.”

Somewhere in this string of eloquence is some semblance of an answer to the question of why we do this. While the world feels like it’s ending each time we lose a pet, the greater loss would be never opening ourselves to heartbreak at all; it’s proof of our capacity to make another creature’s life just a little more beautiful while it walks this earth.

Pets don’t leave much of anything behind, nor do they have much to offer in the grand scheme of this physical world. No seat of power, no great fortune, no memories of heated passion and romance. Even children will carry your legacy through their last name and genetics. Yet for every animal that comes into your life, you inherit a bit of their unadulterated goodness. Loving a pet gives you nothing, really, other than the love itself. I wish I had a better answer than that, but if you know, you know. I think I’ve learned to love better because of every dog I’ve owned. I hope I make them proud. I hope every person I care about feels an amalgamation of their love through me.

I’ll end with a small memory. One evening, I caught my mom lifting our two dogs up, their faces pointed toward a starry sky.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

She smiled. “I don’t think they’ve seen stars like this before. Isn’t it nice to let them see the sky?”

Whether or not they understood didn’t really matter. I took our Jack Russell from her arms, and held him the way she did, his heart—slow with age but still steady—pressed against my palm. In what will hopefully be many years from now, I will be crying in a veterinary clinic, or within the comfort of our home, with him beside me but off to some other world where I can’t follow him just yet. Still, I wouldn’t have traded that moment under the night sky for anything.