The Smithsonian Museum is working with the National Museum of the Philippines to repatriate the remains of indigenous Filipinos who were part of the controversial St.Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

The anguish colonialism has caused, not just in the Philippines, but in other parts of the world, is still present to this day. There are cruelties that certain institutions haven’t properly addressed, wrongs that they have yet to rectify—but with the help of research and investigation, people are bringing these injustices to light.

READ ALSO: Fading Traditions: 3 ‘Vanishing’ Crafts In The Philippines

One such example is “Revealing the Smithsonian’s ‘Racial Brain Collection,’” a recent feature spearheaded by the Washington Post writers Nicole Dungca and Claire Healy. The thorough report discusses the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s (NMNH) unsettling collection of human bones and body parts, particularly brains.

The museum acquired and kept these parts for the purpose of scientific study. However, the feature reveals that the institution gathered these remains “without consent from the individuals or their families.” The most harrowing detail of the report, however, is the fact that many of these remains belonged to people from indigenous groups—including those from the Philippines.

The museum currently holds 30,700 bones and other body parts, 255 of which are brains. Digging deeper, 27 of these brains belonged to Filipinos, including four Igorots (a more general term for the diverse groups of indigenous people that hail from Luzon’s Cordillera mountains).

Dehumanizing Conditions

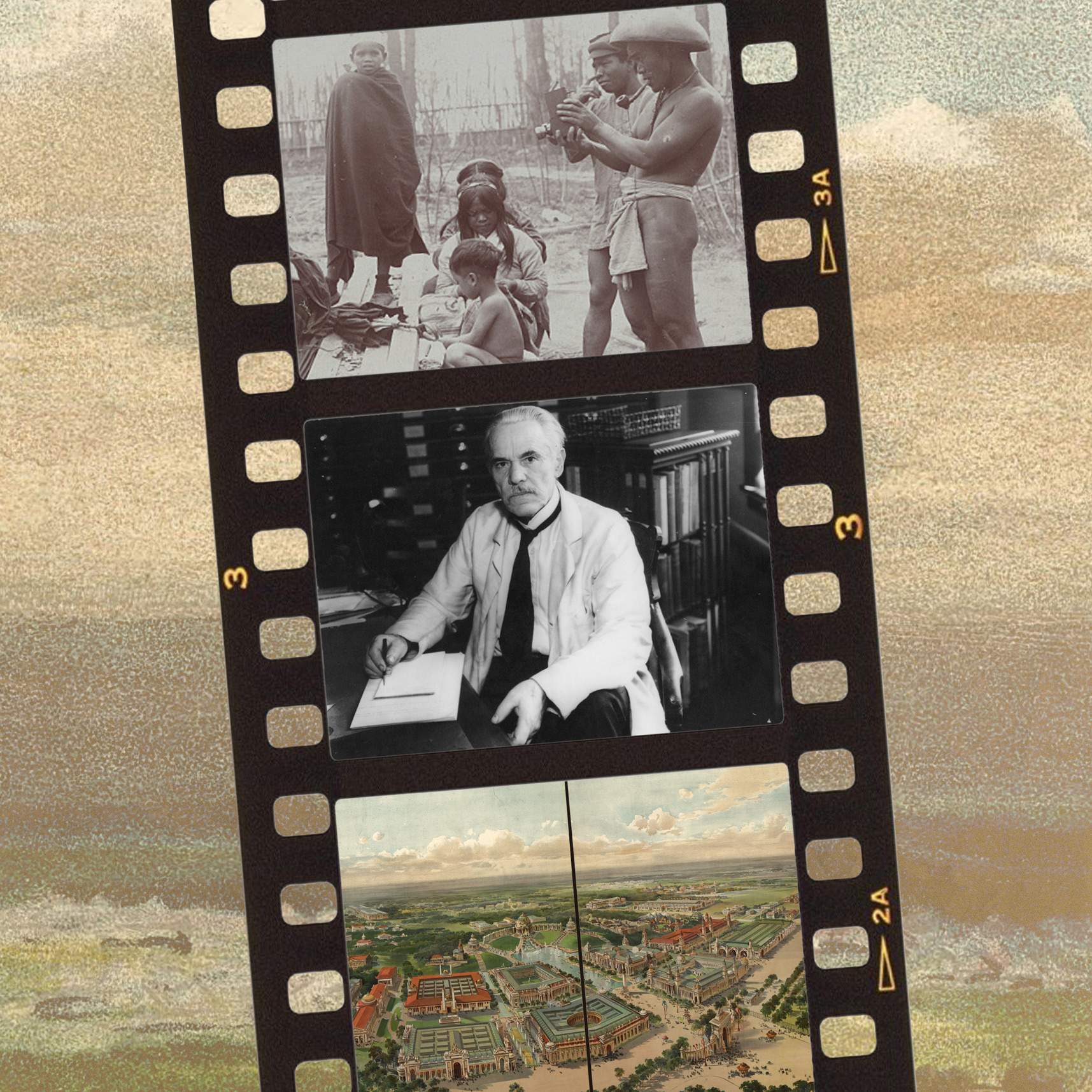

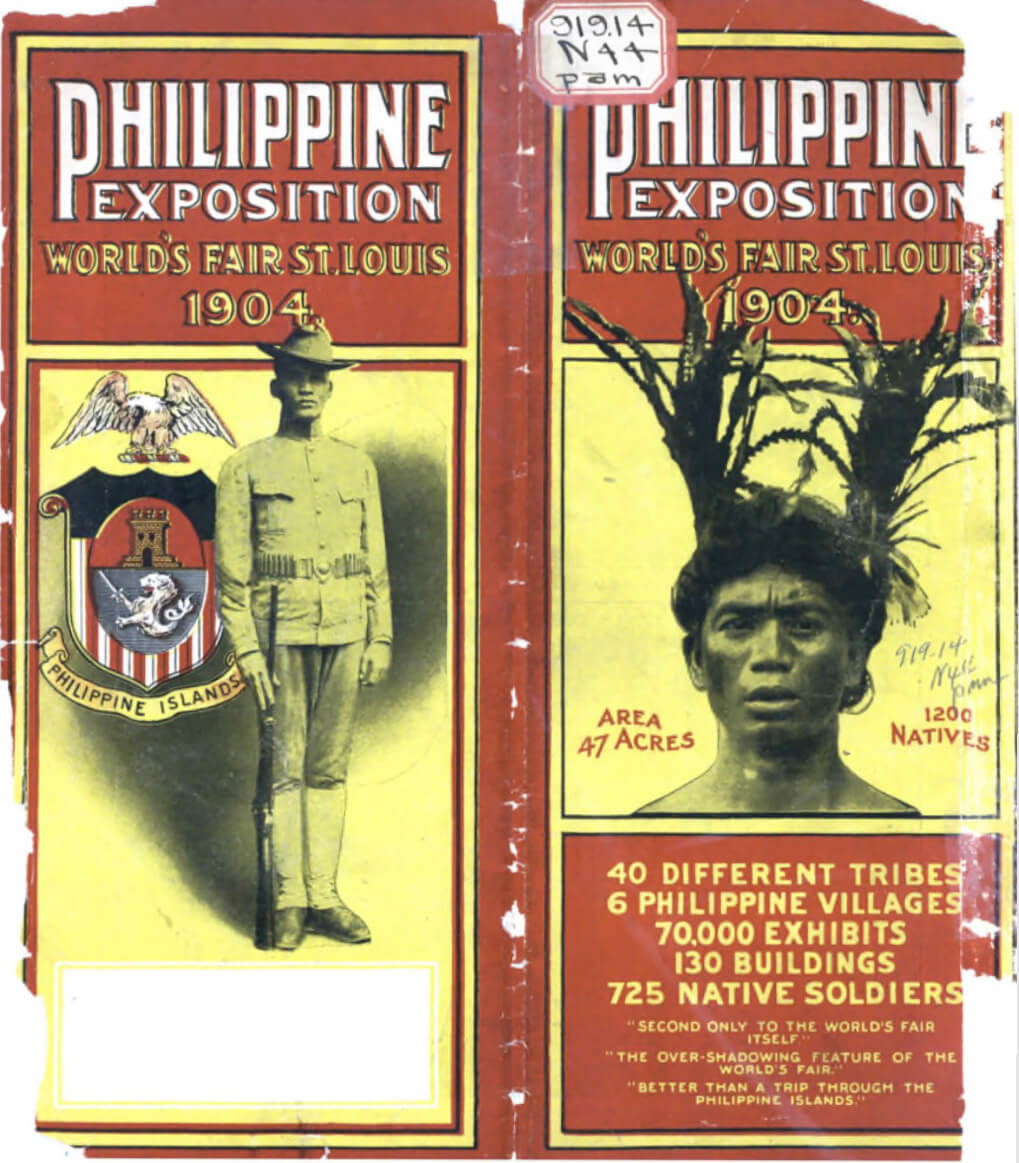

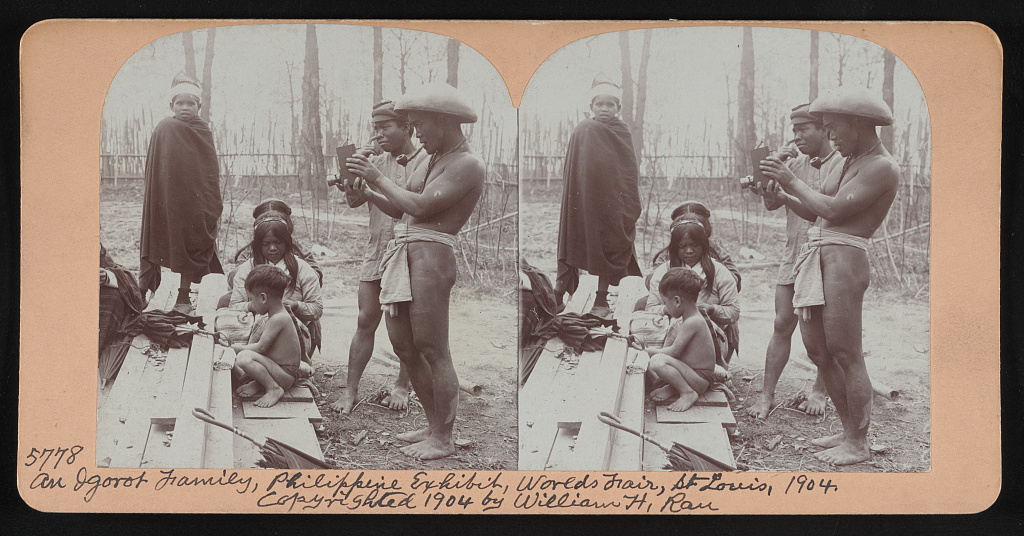

With all that said, how did the Smithsonian NMNH come to acquire these remains from indigenous people? Research points to the controversial St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, which took place just shortly after the U.S. won the Philippine-American war. William Howard Taft—then governor of the Philippines—held the World’s Fair to flaunt the fully-conquered territory.

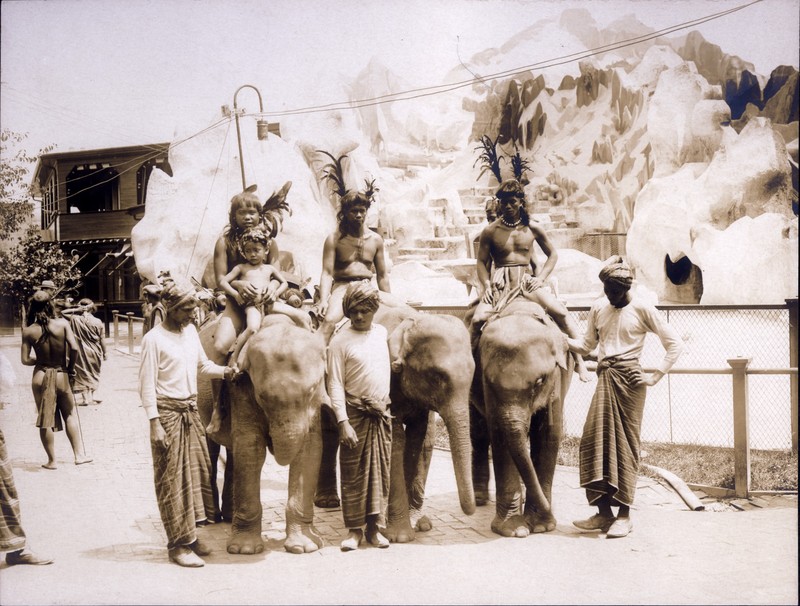

The fair’s main and largest attraction was the 47-acre, artificial Philippine village, as per NPR. Here, attendees gawked at and observed 1,000 indigenous Filipinos through a “living exhibit”—a euphemism for what was basically a human zoo. Those who ran the exhibition forced the Igorot people to eat dogs on a daily basis—something they only did during ceremonial occasions.

“They made them butcher dogs, which is really abusing [their] culture,” shared Mia Abeya—the granddaughter of one of the Igorots who were put on display, with NPR.

The Washington Post also released a separate special feature that focused on the indigenous Filipinos victimized by the U.S. and Smithsonian’s collection. According to the piece, experts are uncertain as to what exactly the U.S. offered to convince the Igorots to travel to foreign land.

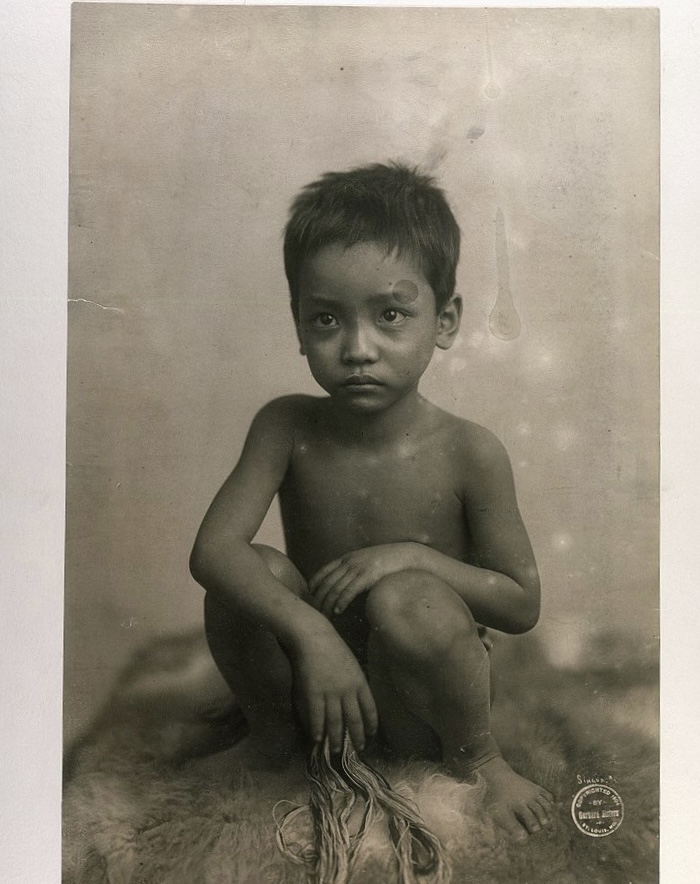

From what little documentation remains from those who were part of the trip, researchers gleaned that some Filipinos were looking for a new experience, while others had no idea why they were on a boat to the U.S.

A Girl Named Maura

The long trip to America was physically taxing for many Filipinos. The constant shift between extreme weather conditions (sweltering hot to frigid), as well as the neglect of those in charge, led to the eventual illnesses of certain members of the Filipino group. This included a young Kankanaey Igorot woman named Maura, who hailed from the mining community of Suyoc.

Historians know very little about Maura—not even a picture of her exists. What they do know is that she was from a high-status family (based on her tattoos), passed away from pneumonia two days before the exhibition, and explicitly wished to have her final resting place in the Philippines.

Upon hearing the news, fellow Igorots at the exhibition mourned for days—a ritual that the public continued to watch and scrutinize. When they visited Maura in a funeral home, they said their blessings, but couldn’t conduct the proper burial rites for her. A reporter promised them that she would return home; but, as the story goes, that never happened.

Unethical Acquisitions

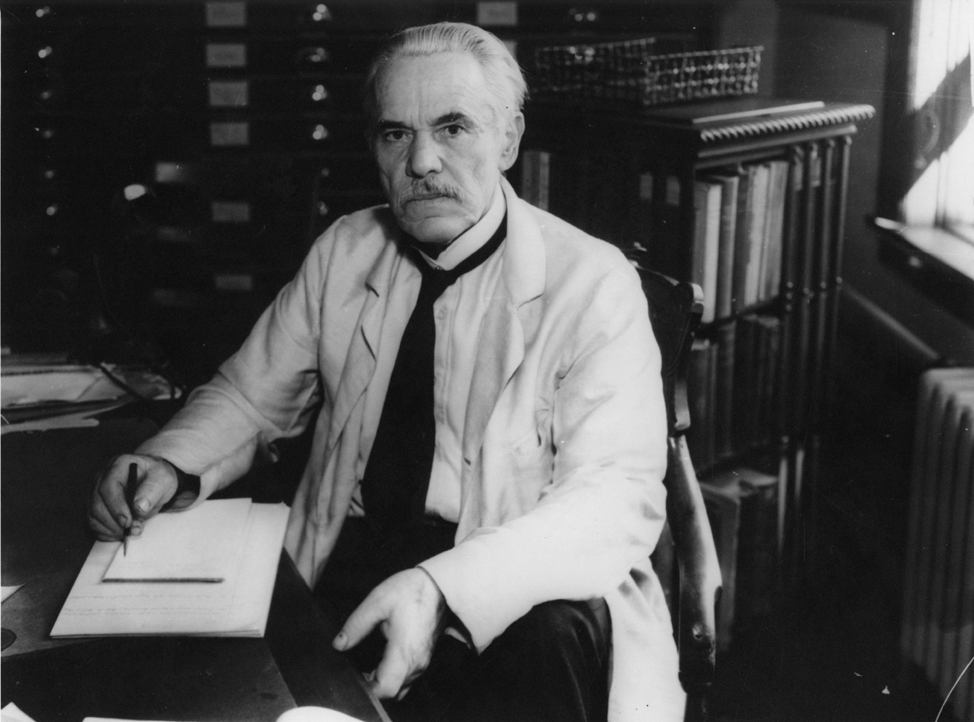

An anthropologist by the name of Ales Hrdlicka was gathering various body parts of the deceased to compose a “racial brain collection.” As he was in charge of the physical anthropology division at the Smithsonian, he aimed to “expand” its collection for use in scientific study.

The reasoning and focus of Hrdlicka’s studies, however, were highly concerning. He believed in White supremacy, and was a member of the American Eugenics Society. To him, the non-consensual collection of these parts would further his goal of proving that Black and Indigenous people were anatomically “primitive.”

When collecting these parts, Hrdlicka would often aim for “unclaimed” bodies. He closely monitored the St. Louis fair in hopes of collecting the brains of the indigenous people exhibited—including that of Maura’s. Black and Sami people were also among those whose parts were collected through unethical means.

According to the Washington Post, top Smithsonian NMNH officials knew about the thousands of body parts held in the institution, though were reportedly unaware of just how expansive the collection actually was. Information on this wasn’t fully disclosed to the public until Dungca and Healy pursued the investigation.

Rectifying Wrongs of the Past

“I know that so much of this has been based on racist attitudes, that these brains were really people of color to demonstrate the superiority of White brains,” shared Lonnie G. Bunch III, the Smithsonian’s secretary, in a recent statement of apology.

“So I understand that is just really unconscionable. I think it’s important for me as a historian to say that all the remains, all the brains, need to be returned if possible, [and] treated in the best possible way,” he continued.

The body parts are cataloged in a way that makes it difficult to trace the exact number of people in its overall collection. However, the institution reports that they’ve been making progress with dedicated staff.

“In the last three decades [the Natural History Museum is said to have] returned 4,068 sets of human remains and offered to repatriate 2,254 more. Those remains belong to more than 6,900 people, because some sets include the remains of more than one person,” wrote the Washington Post feature on the matter.

In light of the news outlet’s groundbreaking feature, the Smithsonian has engaged in talks with the Department of Foreign Affairs, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, and the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP), on the repatriation of the Filipino remains.

Giving a Proper Burial

NMP is currently spearheading the repatriation operations in partnership with its U.S. counterpart. The Philippine institution also recently released a statement on the matter.

“The NMP accepts and supports this effort of the Smithsonian NMNH to do the right thing and facilitate the return of Filipino remains home as a way of rectifying this unfortunate situation,” the museum wrote. “In all cases, the ultimate objective is to turn over the remains to the rightful lineal descendant family or community for proper appropriate action.”

Descendants of the exploited indigenous people are waiting for this promise to be fulfilled. “What happened to our sister [Maura] hurts our hearts,” shared Leonardo Padcayan Buyayao, an indigenous representative of Suyoc.

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, a Kankanaey Igorot and former U.N. special rapporteur, stated that the Smithsonian must return the remains so the respective communities can perform rituals for the dead. As per their customs, such rituals are necessary for the deceased to find peace. Hopefully, that time will come soon—it’s certainly long overdue.

Banner photo by Agatha Romero; Photos from the U.S. Library of Congress website and Smithsonian Institution Archives.