Behind the works of renowned artists like Pablo Picasso and Édouard Manet were women who were not only muses, but also skillful and accomplished creatives in their own right.

The concept of the muse is an old one. In Greek mythology, nine muses served as inspirational goddesses of the arts, sciences, and literature. They produced artists of all kinds, either by birthing them or granting blessings to great heroes and poets. The ancient Greeks worshiped and respected these divine sisters, and they continued to influence artists’ works for centuries. The word “Museum” even traces its origins to the word “Mouseion,” meaning “seat of the Muses.”

READ ALSO: Golden Muse: Picasso’s Portrait Of Marie-Thérèse Walter Is Expected To Fetch $40 Million At Auction

Much like their godly namesakes, human muses also served as sources of inspiration to many renowned artistic figures—so much so that the very concept of “the artist and his muse” has become a common trope.

Then there’s the more unspoken stereotype behind the trope: the languishing muse. A woman whom society either objectifies or underestimates, throwing her under the shadow of a male artist—who, more often than not, is her lover too. The most famous example of this would be Pablo Picasso’s many partners and muses, whom he often exploited and hurt through his philandering ways.

Muses and So Much More

In 1921, Audrey Munson, an American artist’s model, once wrote: “I am wondering if many of my readers have not stood before a masterpiece of lovely sculpture or a remarkable painting of a young girl, her very abandonment of draperies accentuating rather than diminishing her modesty and purity, and asked themselves the question, ‘Where is she now, this model who has been so beautiful? What has been her reward? Is she happy and prosperous or is she sad and forlorn, her beauty gone, leaving only memories in its wake?’”

Indeed, when one hears the names Picasso, Rossetti, or Manet, the specific women in their lives are seldom the first thing that comes to mind. People might think of their genius or skill, but not so much the names of their artistic and romantic partners.

However, these women have always played a significant role in the world of art. Without them, we wouldn’t have many of the paintings we celebrate today. What’s more, there were muses who were great artists in their own right. Some received recognition for their talents during their time, while others received it posthumously.

To simply relegate them to the stereotype of a passive and despondent subject would be a disservice to both their memory and legacy. These muses had autonomy, and were active collaborators as much as they were creators. It’s important to acknowledge the pains and challenges they experienced, but it’s equally paramount to discuss their identities beyond the title of “muse.”

Let’s start by exploring the stories of three women who’ve left a lasting mark on the world of art in their own ways:

Françoise Gilot

Françoise Gilot is arguably one of the most influential female artists out there. She recently passed away on June 6, 2023 at the age of 101. The world remembers her as one of Picasso’s muses, as she experienced a tumultuous 10-year relationship with him.

However, Gilot was an artist in her own right, long before meeting Picasso. She started an art education very early on, and was already making a name for herself during her university days, as revealed by Emma Brockes in a 2016 interview for The Guardian. Gilot developed her own distinctively vibrant and geometric style, making a successful career out of her work even after breaking things off with Picasso in 1953.

A Fiercely Independent Woman

As per Art News, Gilot refused to give into Picasso’s usual manipulative and exploitative behaviors, and fought back in her own ways. She set up a studio in their home in southern France and would go on to paint sentimental and portraits of herself and her children.

In 2021, her oil on canvas painting of her daughter Paloma, entitled “Paloma à la Guitare” (1965), sold for $1.3 million in a Sotheby’s London auction.

“I was not a prisoner. I’d been there of my own will and I left of my own will,” she shared in her interview with The Guardian. “That’s what I told him [Picasso] once, before I left. I said watch out, because I came when I wanted to, but I will leave when I want. He said, nobody leaves a man like me. I said, we’ll see.”

A Successful Career of Her Own

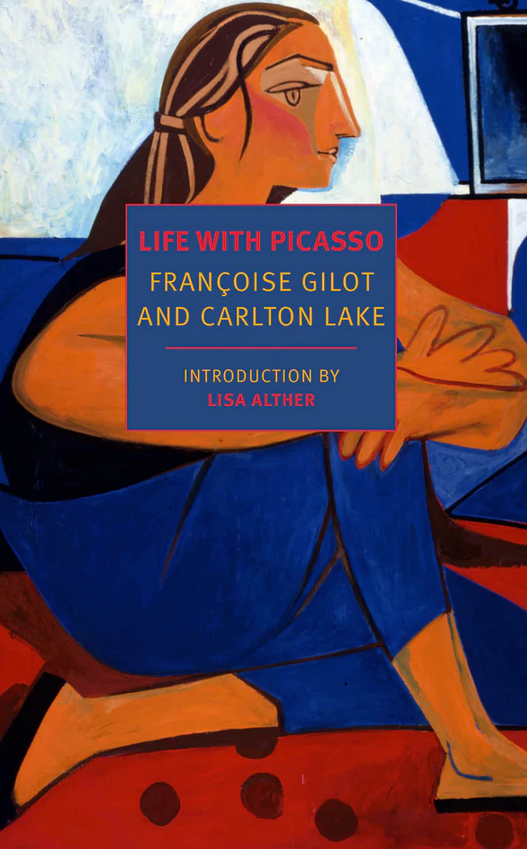

After separating from Picasso, she would go on to write a bestselling and candid memoir of her life with him in 1964, entitled Life with Picasso (now considered a significant piece of literature in women’s art history).

Gilot continued her artistic endeavors in a small studio she established toward the end of the 1970s. Some of the world’s greatest artistic institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, have exhibited her pieces, according to Smithsonian Magazine. In 2009, President Nicolas Sarkozy made Gilot an office of the Legion of Honor, France’s most prestigious honor of merit, as per The Art Newspaper.

“To see Françoise as a muse [to Picasso] is to miss the point,” shared Simon Shaw, Sotheby’s vice chairman for global fine art, to the Associated Press. “While her work naturally entered into dialogue with his, Françoise pursued a course fiercely her own—her art, like her character, was filled with color, energy and joy.”

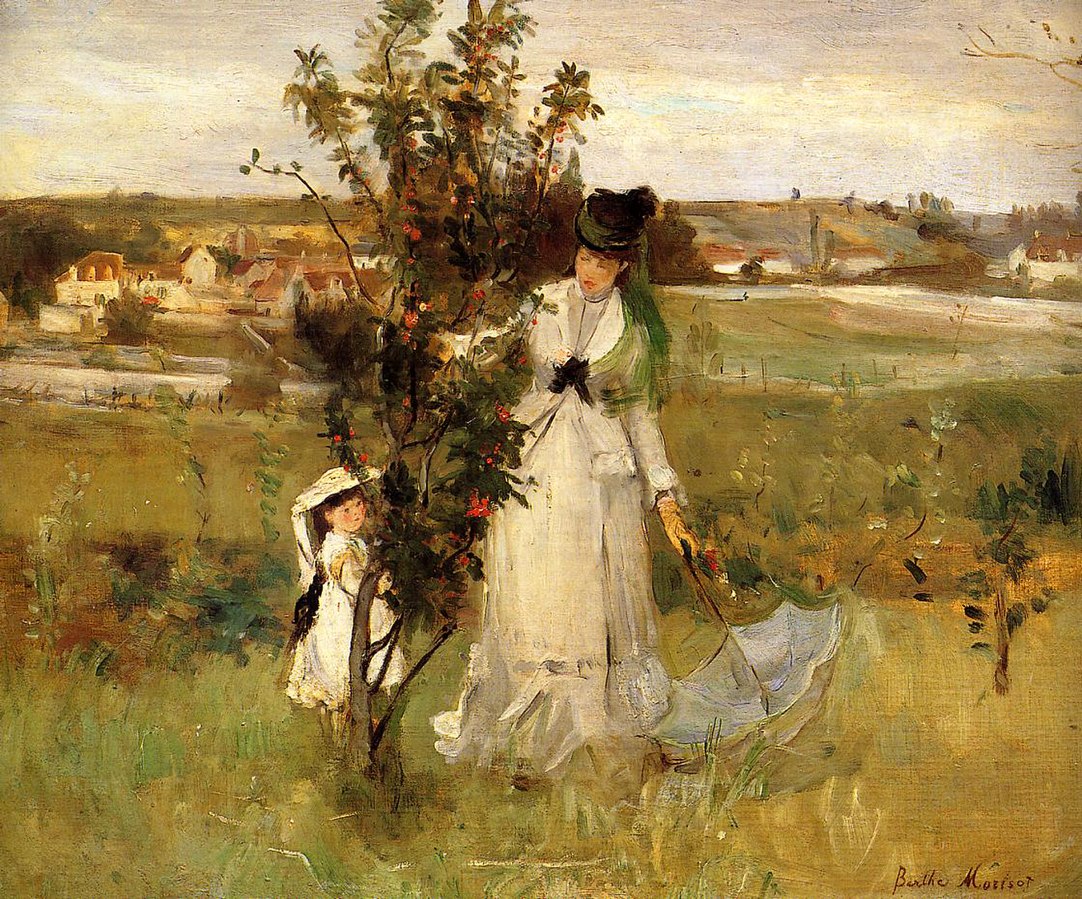

Berthe Morisot

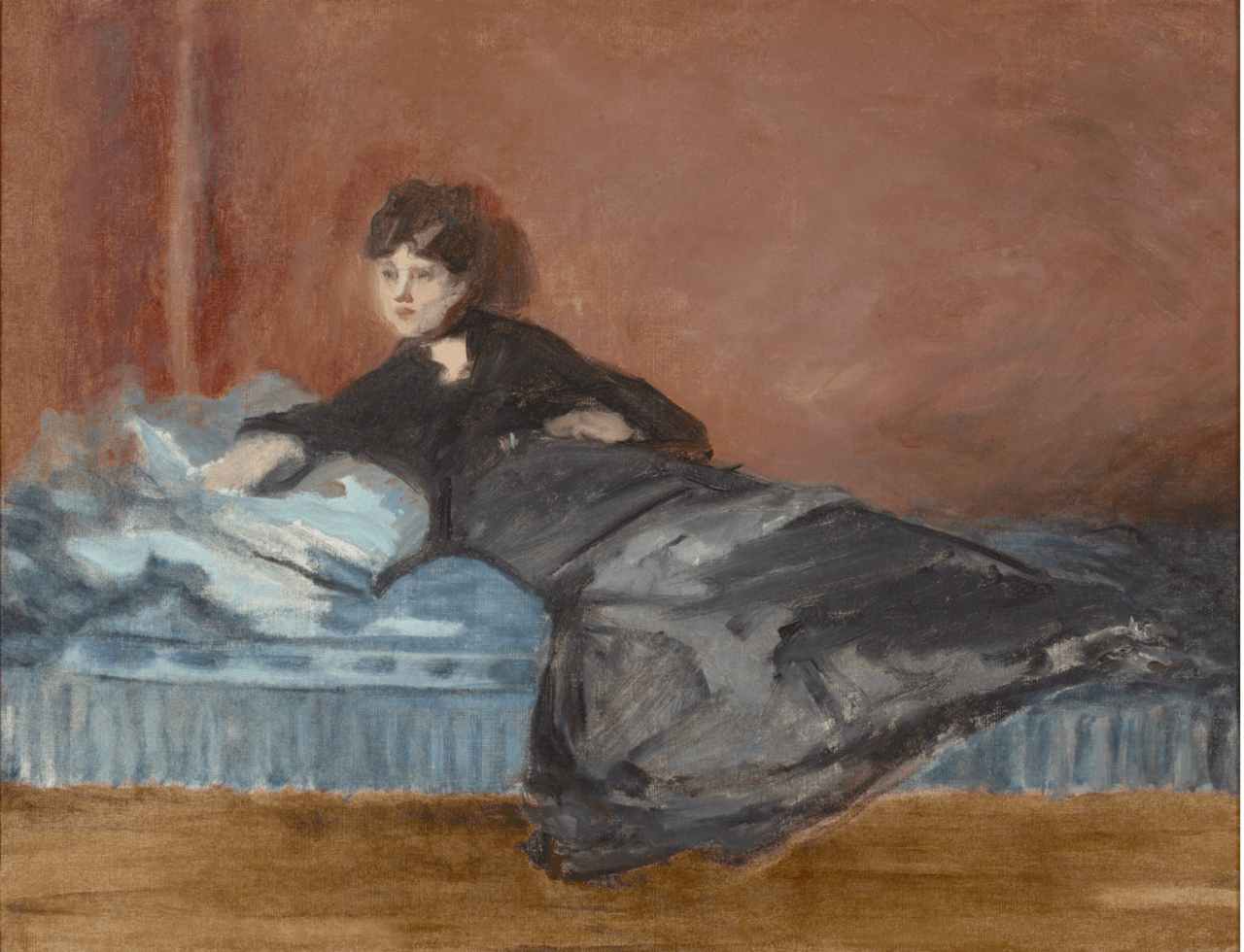

Berthe Morisot served as the inspiration behind many of Édouard Manet’s paintings. In fact, the artist had painted her more than any other model he’d known—11 times, to be more specific. Manet had her model for two among his most popular pieces, namely “Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets” (1872) and “Repose” (1871).

Pushing Boundaries

Morisot was born to an upper-middle class family in 1841 France, yet went against the decorum expected from a lady of her status to model for Manet. At the time, society considered a career in artistic modeling as highly inappropriate, as per an article from France Today. Still, the young woman continued the endeavor, partly due to her personal admiration for the artist.

Morisot wasn’t just a model, but also a highly-skilled painter. She was one of only two women who were members of Paris’ Impressionist circle (the other being Mary Cassatt). She also got to exhibit her work in the prestigious Société Anonyme des Artistes-Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs—the first show that featured works of the Impressionists, as per The National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Making a Name for Herself

Morisot’s mother had supported her daughter’s love for the arts since she was young. Later on, she would cross paths with the renowned Manet.

For years, they had shared a close professional relationship—as to whether it was romantic, experts are unsure. Certainly, the older artist regarded Morisot with tenderness and respect, as portrayed through his portraits and correspondences.

Morisot’s work was limited to what society deemed as “appropriate” for women to paint at the time. These included feminine, intimate, and domestic scenes and portraits. Critics praised her pieces for their “intuitiveness, spontaneity, and delicacy.”

Some of Morisot’s most famous works include “The Cradle” (1872), “The Mother and Sister of the Artist” (1869–1870), and “Woman at Her Toilette” (1880).

A Lifelong Pursuit

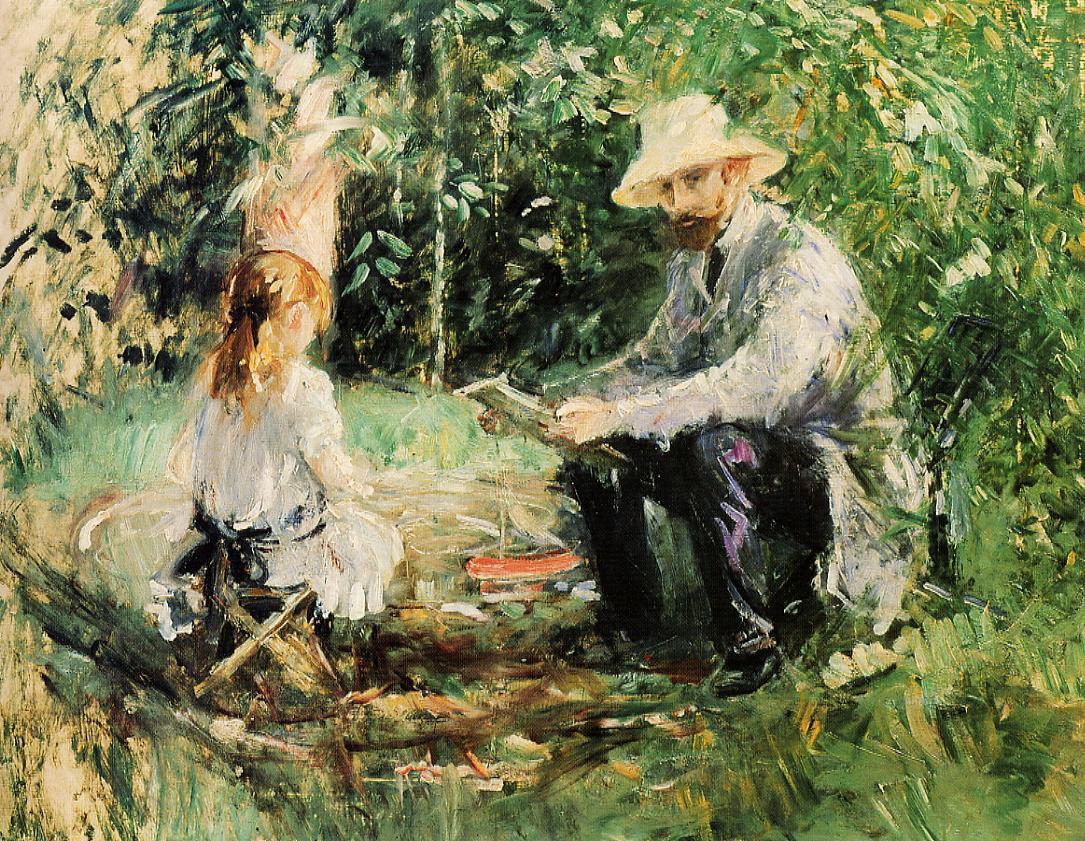

Morisot remained unmarried until the age of 30—an unusual circumstance, though she appeared unperturbed by it. That said, experts believe that Manet wanted to provide a secure future for his collaborator and muse by marrying her to his brother, Eugène. Conveniently enough, Eugène revealed his feelings for Morisot in 1874, and the two wed.

Manet would stop painting the married woman, though he did create one last portrait of her in 1874, “Berthe Morisot with a Fan,” depicting her wearing her wedding ring. Morisot’s later portraits would often feature her husband Eugène and her only daughter, Julie.

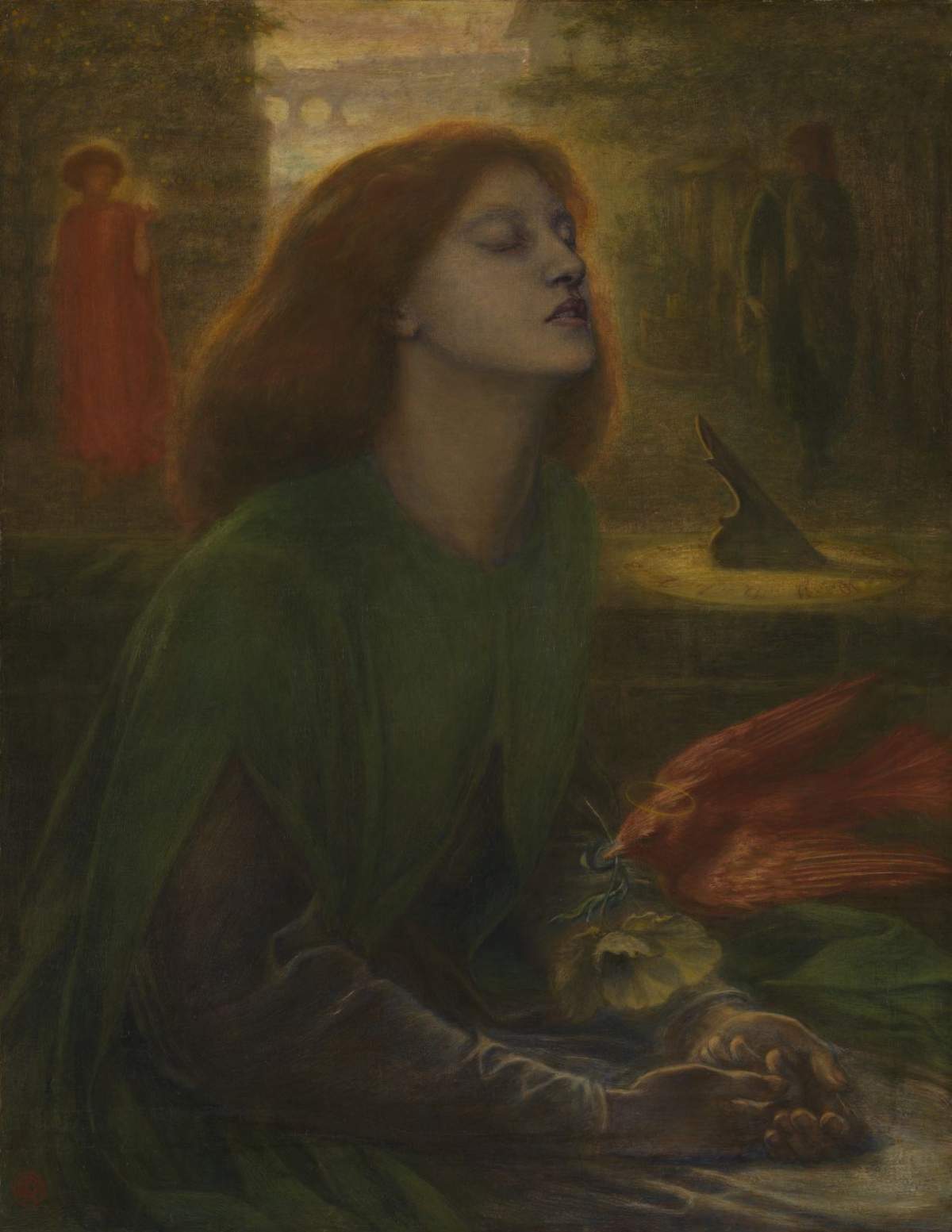

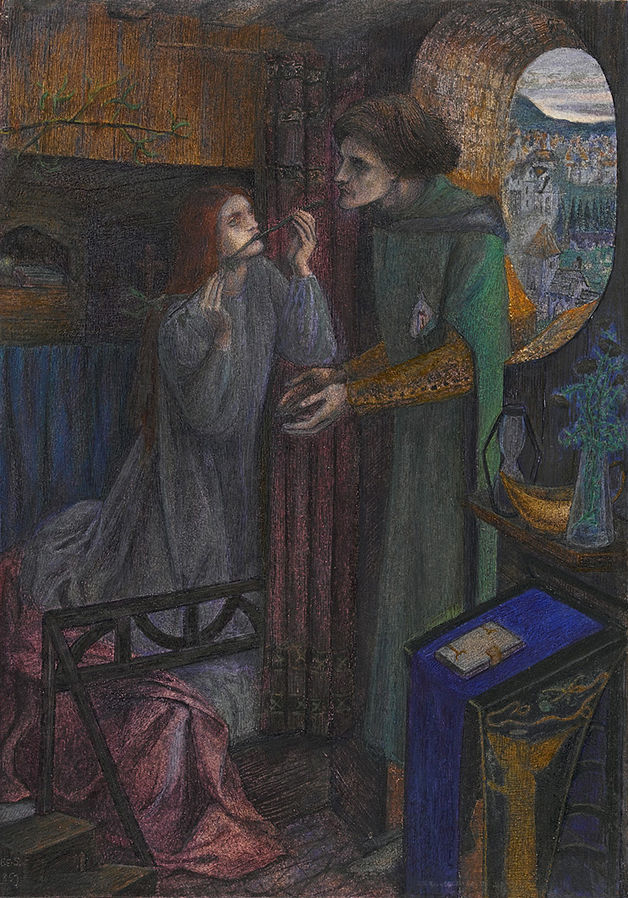

Elizabeth Siddal

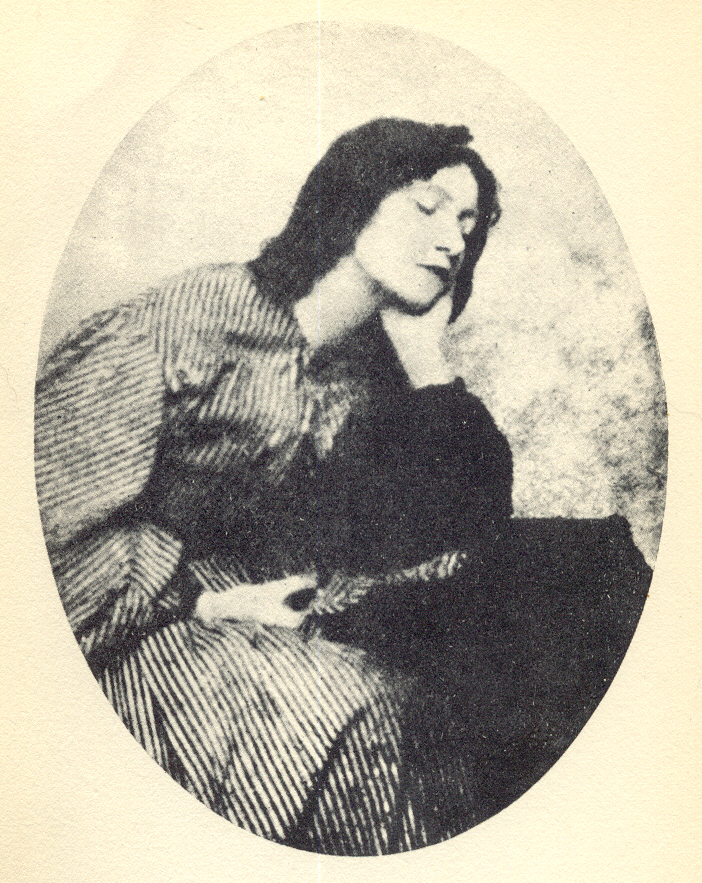

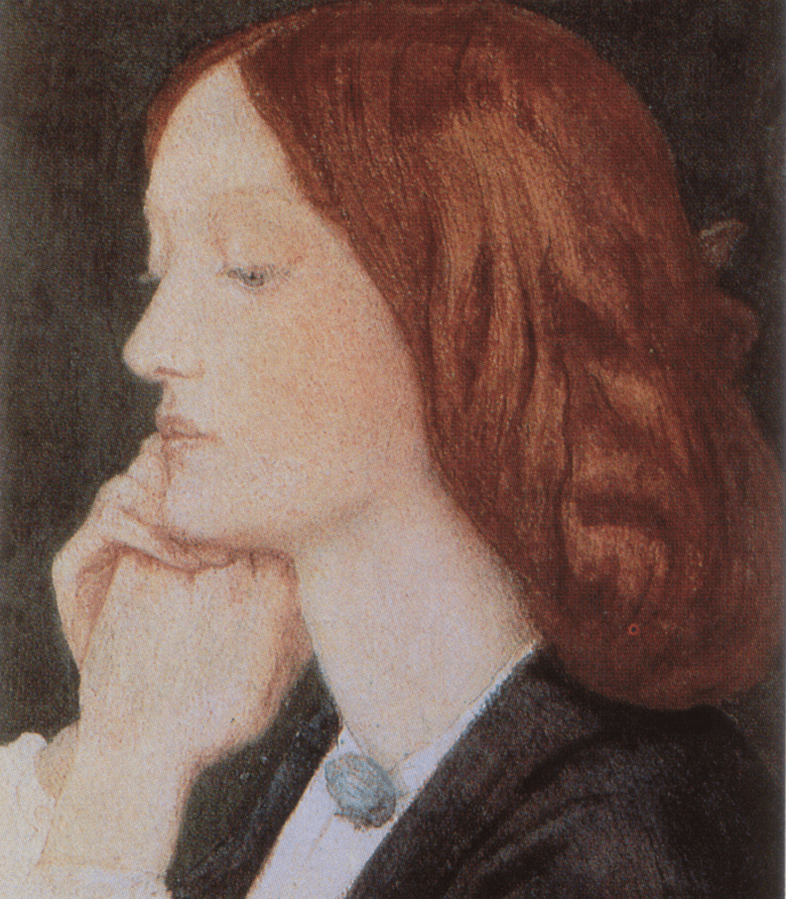

Great works of art wouldn’t exist without the face of Elizabeth Siddal, the wife and muse of English painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Siddal took up a job as an artistic muse to escape the poor working conditions in a milliner’s shop.

Siddal worked part time in a hat shop while modeling for members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—an elite secret society composed of artists like Rossetti. Eventually, she made enough money to quit the hat shop altogether, according to Lucinda Hawksley in an article for BBC Culture.

A Recognizable and Inimitable Face

Rossetti painted Siddal thousands of times, according to the same BBC Culture article.

Siddal also worked as a model for Sir John Everett Millais’ “Ophelia,” which was what shot her to fame. The macabre yet captivatingly elegant painting features Shakespeare’s Ophelia, a noblewoman from Hamlet, who lies partially submerged in a brook, glassy-eyed with colorful flowers floating around her.

Ophelia’s wispy frame, copper red hair, and pale complexion can be attributed to Siddal, who sacrificed a lot to model for the piece. She had agreed to lie in a tub for hours—long after its water turned icy cold, which resulted in her falling ill.

Talent Amid Turbulent Times

Siddal married Rossetti after a decade-long engagement, though the relationship (like many artists and their muses) was one filled with challenges—namely Rossetti’s consistent unfaithfulness, a stillborn child, and Siddal’s addiction to laudanum. The latter would end up resulting in the suspected suicide of Siddal, who passed at the young age of 32.

Despite the tragedy of her death, Siddal was determined to make it on her own as an artist when she was alive. In 1854, she began a painting career under the tutelage of Rossetti, creating works that patron John Ruskin deemed as “genius.”

Siddal was the only woman whose work was displayed in an 1857 Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition. It was here where Charles Eliot Norton, a famous US collector, purchased her painting entitled “Clerk Saunders.”

Shortly after, she enrolled in the Sheffield School of Art. Sadly, what transpired during these years of her life remains a mystery, according to BBC Culture. One thing’s for certain: though Siddal’s legacy is hidden beneath the famous works she’s modeled for, it’s no less significant.

Britain’s Tate Museum recently opened an exhibition called The Rossettis, which features Siddal’s works alongside those of her husband and sister-in-law Christina, and will be running until September this year.

Banner photo by Françoise Gilot from the Sotheby’s website.