As the legendary animation studio turns 40, we reflect on how its films shaped not just pop culture, but the way we understand ourselves and the world’s quiet complexities.

SM Cinema recently joined Studio Ghibli Fest 2025, celebrating some of the studio’s most beloved works as it turns 40 this year. Though a few personal favorites were missing, I finally saw what I consider Hayao Miyazaki’s masterpiece, Princess Mononoke, on the big screen. Hearing the narrated introduction, seeing Ashitaka ride his red elk through the forest, and listening to Joe Hisaishi’s soaring string score gave me goosebumps—it was a sensory reminder of why Ghibli moves us so deeply. And so I put it all into words in celebration of the works that’ve undoubtedly changed pop culture and the lives of those who hold these stories close to their hearts.

READ ALSO: Jaws At 50: The Story Behind Steven Spielberg’s Landmark Masterpiece

The Universal Appeal Of Studio Ghibli Films

Studio Ghibli is often associated with Hayao Miyazaki, but it began as a collaboration with filmmaker Isao Takahata and producer Toshio Suzuki in 1985. Backed by publisher Tokuma Shoten, they launched Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, a dystopian tale of a princess saving a dying planet. Its success set Ghibli on a path of nuanced storytelling, complex themes, and breathtaking animation that speaks to audiences of all ages.

Not all Ghibli films are hits, but here’s one thing most people can agree on: there’s going to be at least one movie that’ll change the way you see yourself, the world, and animation’s limitless power as a medium.

Like Real People Do

Ghibli doesn’t lean into dichotomy. If its films share one common thread, besides a distinct visual language, it’s their propensity for avoiding black and white storytelling. And that makes sense: life is seldom categorized into good vs. bad, us vs. them.

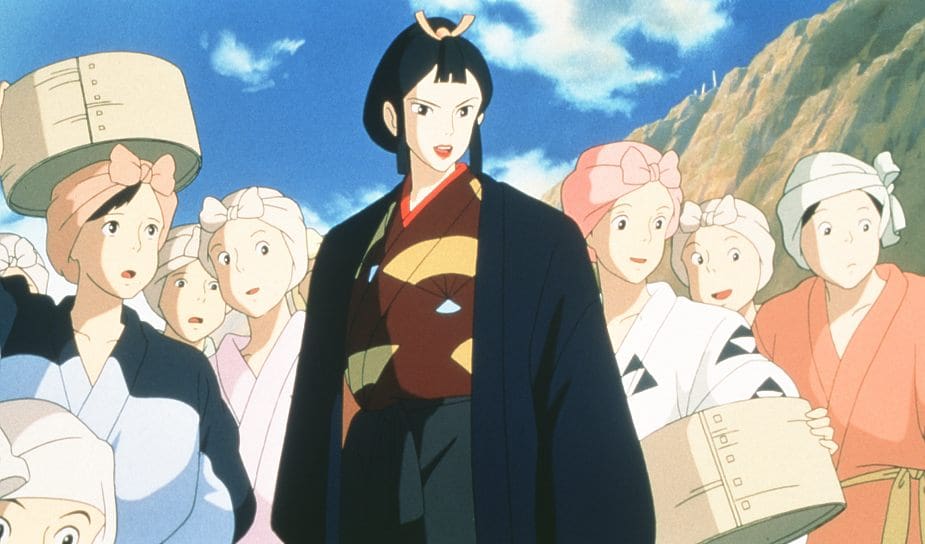

You can still hate Ghibli characters, but the point is that the films never impose an opinion. Coming out of Princess Mononoke, a friend pointed out how much he wanted its ambitious industrialist Lady Eboshi to die. I countered that she rescued and gave jobs to women from brothels, even lepers, to which he rebutted: “Yeah, then she exploited them for free labor to the point of exhaustion.” Touché, and that’s the magic of these films: every rewatch gives you something new to think about, even if you’ve seen them a million times.

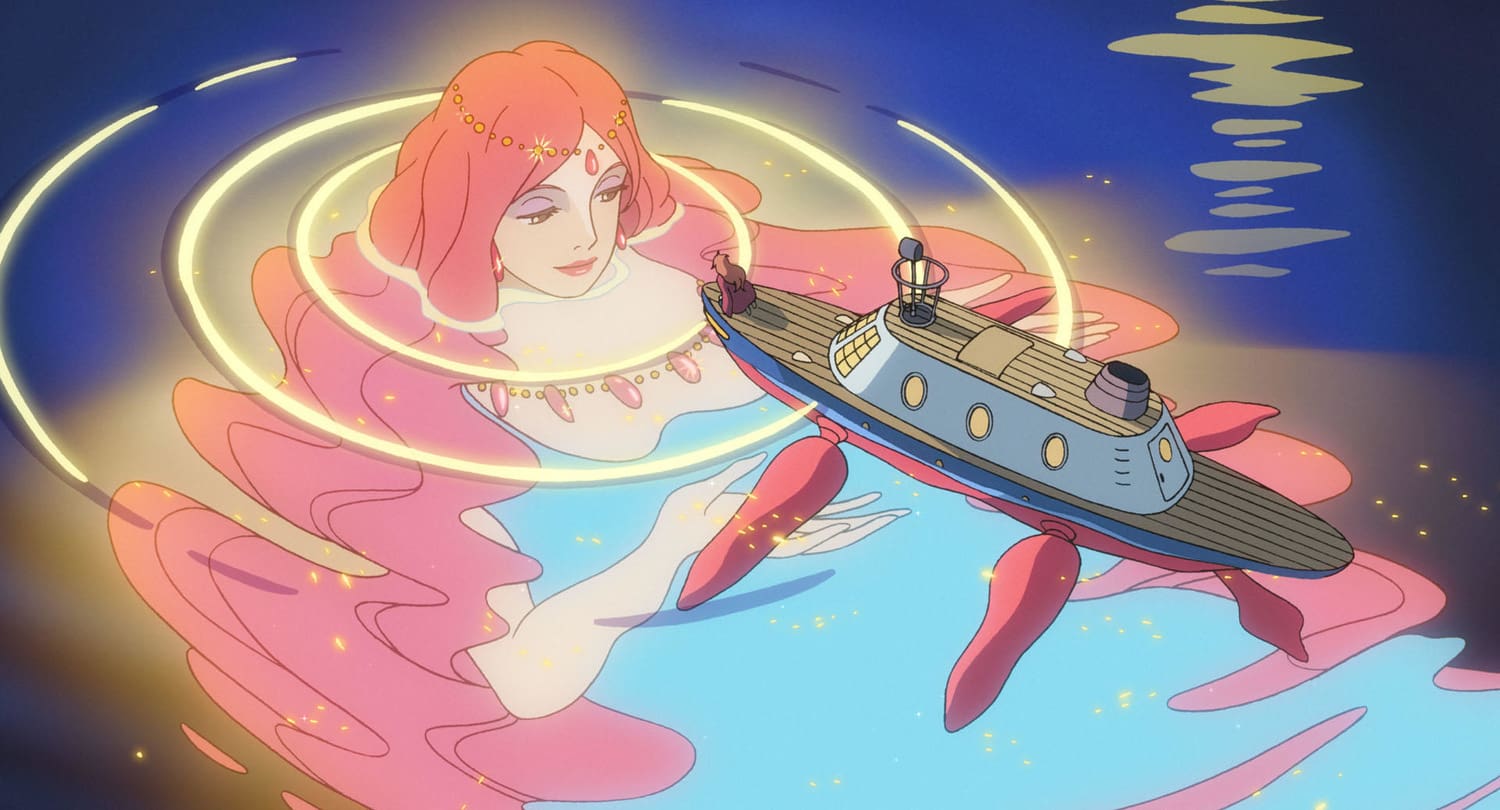

The eponymous protagonist of Howl’s Moving Castle is vain, petty, and immature, but aren’t we all, to some extent? No-Face is greedy and clingy, initially unaware of what a sincere, healthy connection looks like until he experiences it himself. The sorcerer Fujimoto, despite being Ponyo’s antagonistic figure, is really just an overprotective father who loves his wife and children. The people of Irontown and the powerful animal gods in Princess Mononoke both want to protect their homes.

It’s never “root for this character,” but rather, “here’s someone who reflects all the worst and best of humanity.” No studio understands the necessary co-existence of darkness and light the way Studio Ghibli does.

Women And Love, As Told By Ghibli

Then there are the women of Ghibli: so whole and unabashedly themselves. They cackle, scream, sob (we’re talking full-blown snot-in-your-nose crying), get dirty, make selfish decisions, hurt people—and that’s what makes them so memorable. In a world where women often pander to the desires of men, Ghibli girls are free to exist as they are, still wholly unique individuals on their own: even when they fall in love, their existence isn’t tethered to their male counterparts.

“I’ve become skeptical of the unwritten rule that just because a boy and girl appear in the same feature, a romance must ensue,” writes Miyazaki in the English translation of his essay collection, Starting Point (1979-1996). “Rather, I want to portray a slightly different relationship, one where the two mutually inspire each other to live— if l’m able to, then perhaps I’ll be closer to portraying a true expression of love.”

The Merry-Go-Round Of Life

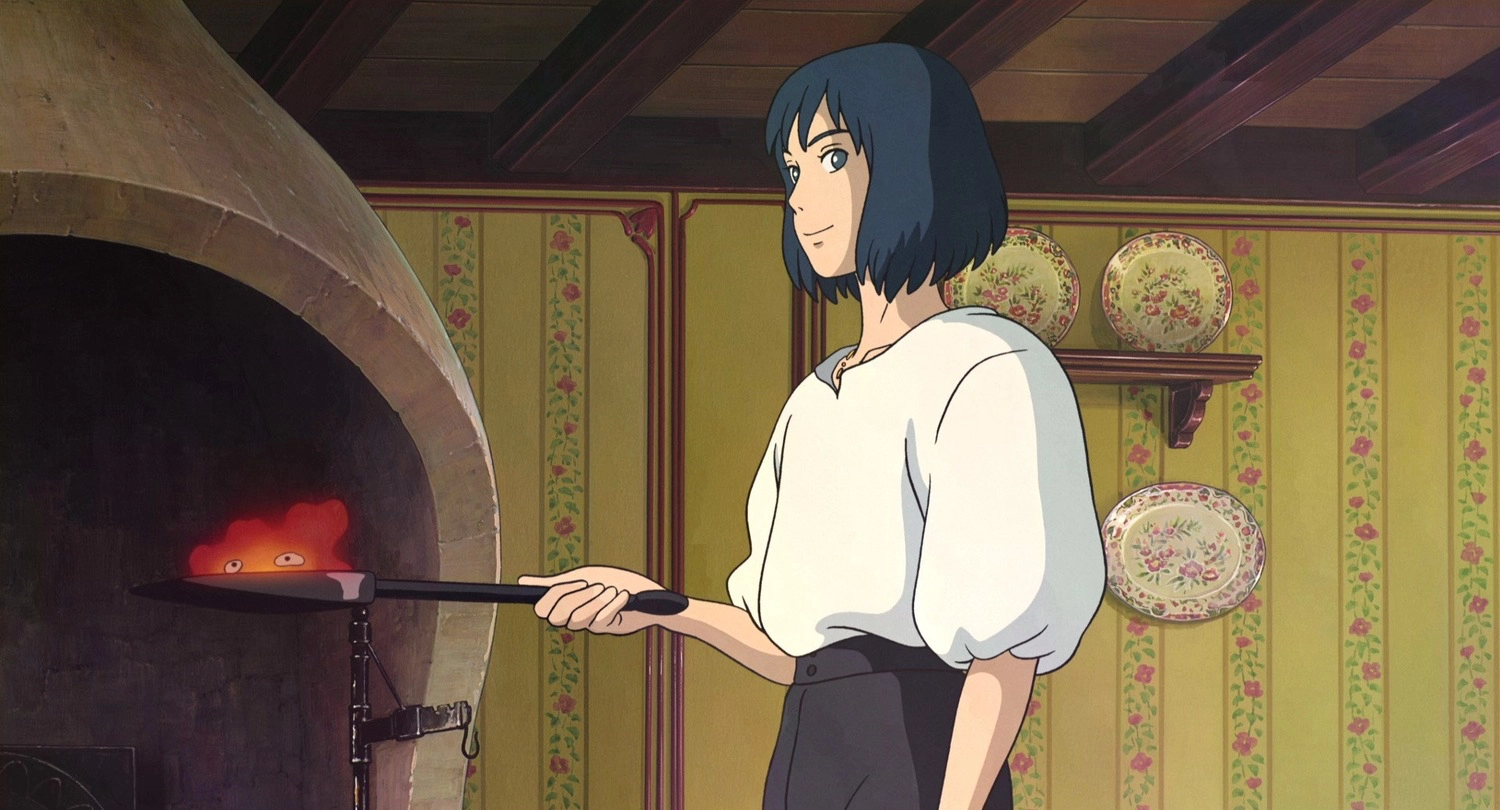

While Ghibli is known for portraying the fantastical in breathtaking detail, it doesn’t overlook the beauty of the mundane. Raindrops dripping from leaves; succulent meat and eggs sizzling in a pan; two lovers biking uphill; someone getting dressed—the comfort audiences derive from its films is born from a visual language that magnifies the ordinary, expanding it into something almost divine.

This feature wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the scores of Joe Hisaishi. The hundreds of lo-fi Ghibli covers and orchestral tributes online are a testament to his lasting influence on the studio. From the poignant “One Summer’s Day” in Spirited Away to the ever-iconic “Merry-Go-Round of Life” in Howl’s Moving Castle, Hisaishi’s pieces are so closely tied to a film’s emotional beats that just listening to them will make you tear up or remember exactly how it all plays out.

Ghibli’s hand-drawn, watercolor-style backdrops and lines aren’t just technical feats; they’re also mementos of the human touch and experience that fuels every frame. That’s why the AI-generated Ghibli trend from earlier this year was, quite frankly, an insult to everything Miyazaki and his studio stand for. The filmmaker creates works about ecological collapse and the dangers of uncontrolled industrialization for a reason: it’s a reminder of what we stand to lose when we forget about our empathy and compassion.

I’ll end with this: Ghibli films remain a warm sanctuary we return to in an entertainment world overrun with mindless AI schlop and endless short-form content. We can only hope Miyazaki keeps breaking his retirement promises. Even if his next work doesn’t rival his greatest masterpieces, as long as he reminds us of life’s beauty—and what we can give back to it—that would be enough.

Select Studio Ghibli films can be streamed on Netflix Philippines.

Film stills courtesy of Kinorium, GIFs courtesy of GIPHY.