A solar-powered installation by Liter of Light reimagines how light, craft, and collective action shape cultural and climate futures.

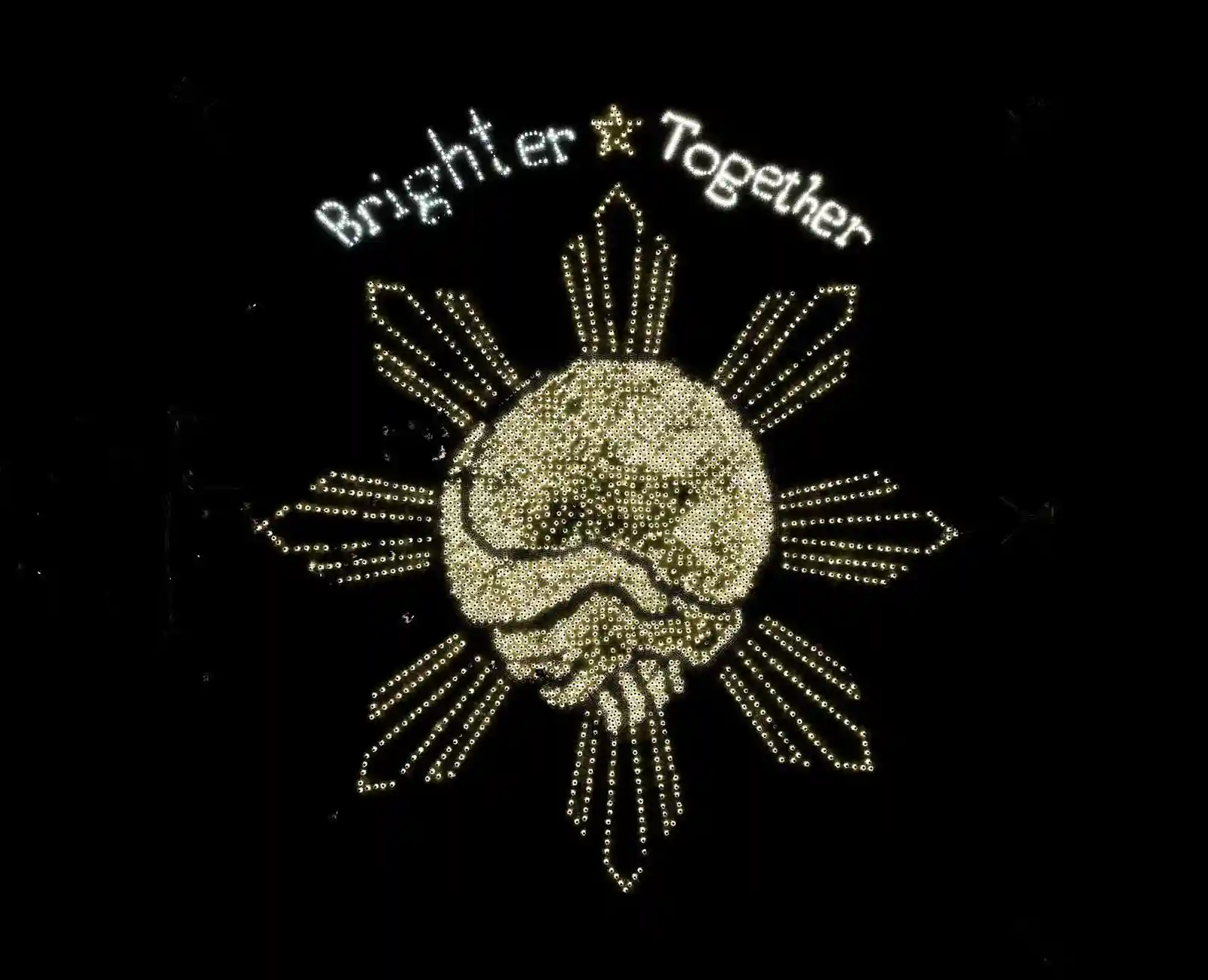

On the evening of July 1, 2025, the grounds outside the National Museum of the Philippines lit up with a calm intensity that drew people in. A large-scale installation of solar study lamps—each resting in hand-molded ceramic—depicted two hands clasped together, a rising sun, and the phrase “Brighter Together” glowing across the museum lawn. The installation formed part of a wider effort to distribute 3,500 solar lamps to communities in the country.

This large-scale installation—spearheaded by Liter of Light in collaboration with Sun Life Philippines, the National Museum, and Odangputik Art Space—not only broke a Guinness World Record for the largest solar light art installation; it also reimagined how public space can serve as a site for cultural expression and environmental advocacy. Amidst heavy rains and unpredictable weather, volunteers and collaborators came together—mounting each light by hand, undeterred, and united by purpose.

More than a record-breaking feat, “Circle of Light” became a shared lens—fusing sustainability with community storytelling. For Jorell Legaspi, Deputy Director-General for Museums at the National Museum of the Philippines, the project reveals the evolving role of institutions in civic life.

“’Circle of Light’ invites community participation and sustainable thinking,” he explained. “It expands our understanding and appreciation of cultural preservation, and supports the idea that heritage is not only what we inherit. Creative expression may also be a shared experience, in which artists serve as teachers or facilitators.”

REAL ALSO: In Our Stillness: Sa Tahanan Co.’s Echoes Of Home

Here, the museum is not merely a place of objects but a living platform—one that enables new rituals of gathering, imagining, and reconfiguring futures. Projects like this blur the lines between heritage and present-day relevance, suggesting that heritage, like light, can be both archival and active.

“At the National Museum, we see projects like this as opportunities to evolve our practice,” Legaspi continued. “To challenge conventions while balancing our role as custodians of sites, objects, and traditions.”

The resulting installation didn’t just commemorate—it convened. It held space for a moment of pause, where art met advocacy under the open sky. Participants weren’t simply spectators but co-dreamers in a shared climate narrative—illuminated, quite literally, by the power of collective imagination.

Designing Light, Sparking Dialogue

For over a decade, Liter of Light has championed a grassroots approach to energy access—repurposing simple solar technology while empowering local communities to build, maintain, and distribute their own hand-built lighting solutions. Its mission has always been people-powered, rooted in the belief that progress is most sustainable when it is shared.

“Art is a great communicator,” shares founder Illac Diaz. “By using purpose or advocacy in art, it was an easier way to communicate rather than just simply talking about the problem. People can get involved—once you get people involved, it becomes personal.”

This installation marked a notable shift in how the organization connects with audiences. Where energy poverty is often confined to reports and statistics, “Circle of Light” rendered it visible—offering an emotional, participatory experience that honored both process and purpose.

“We really felt that there was this tipping point where people wanted transparency— that after the event, there was going to be a real impact,” Diaz reflects. “The journey was more important than the destination. Seeing the joy of bringing income to handicrafts, empowering women artisans who assembled the circuits, and distributing the lamps to communities— that is the real story.”

This spirit of inclusion and co-creation shaped not only how the project was built, but how it was received. Still, its strength also lies in acknowledging that there is more to explore. The design—a rising sun, joined hands, and a unifying phrase—was clear and uplifting, yet future iterations might venture into more open-ended artistic expressions, allowing room for layered interpretation and deeper reflection.

Around the world, artists have continued to push the possibilities of environmental art. Olafur Eliasson’s “Ice Watch” placed melting glacial ice in urban plazas to make climate change immediate and sensory. Agnes Denes’ “Wheatfield – A Confrontation” transformed a Manhattan landfill into a golden field of grain, forcing questions about land, labor, and value. These works are reminders of how poetic disruption can shift public consciousness..

In comparison, we are still early in this journey—experimenting with the ways art, advocacy, and community can cohere in our local context. But the potential is immense. Projects like “Circle of Light” lay important groundwork: forging partnerships, inviting participation, and sparking dialogue across disciplines.

This would not have been possible without the support of Sun Life Philippines and institutional collaborators who believed in the project’s purpose. As more companies and organizations embrace the intersection of sustainability and culture, there is an opportunity to go even further—co-creating not just messages, but meaning.

Fired By Hand, Grounded In Earth

While the light captured the eye, it was the ceramic encasements that grounded the installation—giving it form, weight, and material soul. Each base was handcrafted by Odangputik Art Space, an artist-run initiative founded by Ianna “odangputik” Engaño and Lin Bajala, whose work bridges material practice with advocacy, research, and education.

“When we were crafting the lamp-holders, even the prototype was done by hand,” Engaño explained. “At the center, a handshake—a universal symbol of solidarity. It references bayanihan, and speaks to our mission to build projects that integrate science, art, and community.”

READ ALSO: Vibrant Identities: Nuyda Estate Launches Open Edition Prints Of “PRIDE” By Justin Nuyda

The ceramic bases were produced through Odangputik’s Pagtanom Internship Program, where interns and apprentices took part in each stage of production. What emerged was not just an object, but a process—a collaborative act of knowledge-sharing, skill-building, and cultural continuity.

“For me, as a Filipino artist, I aim for the preservation and progression of Philippine ceramics,” Engaño continued. “We became one of the pieces that will start a bridge—which shall aid the students in energy-scarce areas in reaching their dreams.”

In this work, the ceramic component is not merely a structural base—it is a vessel of meaning. Its form holds the quiet labor of hands, the ethic of interdependence, and the enduring presence of the artist-craftsperson as both maker and cultural agent

“Artist-run spaces are not only contributing to the future of society—we are moving the status quo in the present,” Engaño shared. “When art is no longer enough, we push for collaboration. The greatest challenge is to respect the science, the art, and the people who carry both.”

As the light extended outward, it was these fired earth forms that held it in place—rooting vision in material presence, and translating intention into touch, labor, and lasting care. They grounded the installation not just in space, but in the hands and histories that made it possible.

Light Beyond The Record

For Illac Diaz and the Liter of Light team, the Guinness World Record was never the destination—it was a waypoint. The installation may have captured public attention for its scale, but its real significance emerged in the days that followed, as thousands of solar lamps left the museum grounds and began their journey into homes across the country. There, they would light study tables, dinner conversations, and dreams still in the making.

“The World Record is a standard—a global metric— but not the meaning. The real impact is in what happens after,” Diaz explained.

Following the event, 3,500 solar lamps are being prepared for distribution to learners and families in off-grid communities. Designed to last up to five years and provide 12 hours of light per day, these lamps are not commemorative objects—they are vital tools for access, dignity, and learning.

Unlike campaigns that culminate with a single moment, this one was designed for continuity. The ceramic bases that once formed part of a glowing collective image now rest in schoolrooms, kitchens, and community spaces—carrying light where it is needed most.

Diaz emphasizes that sustainable impact begins with local investment. “Most of the money is invested back in these communities and to artisans for their art,” he shared. “Instead of importing finished products, we believe in honoring and celebrating the hands that create.”

It’s a model that challenges the conventions of development—moving beyond temporary aid toward community-rooted systems of care, skill, and sustainability. By centering local makers and keeping the creative process embedded in the hands of those it serves, the initiative builds more than objects. It nurtures capacity.

This approach reflects a global shift—from charity to collaboration, from visibility to shared authorship. When light becomes a tool for empowerment, its impact is not defined by how many lives it touches, but by how it is lived: in the focused hours of study after sundown, in the return of skilled work once limited by daylight, and in communities that now stay, gather, and grow together into the night.

Tracing The Afterlight

The installation’s power lies not only in its presence—but in its afterlife. For Liter of Light, this wasn’t a moment of display; it was a working model. By embedding craft, collective effort, and function into public art, they offer a blueprint for how creative practice can scale into sustainable systems.

“What you see here is actually the work we are scaling around the world,” Diaz said. “What we do here serves as a litmus test of our success—but also our capacity to grow our work from the Philippines to now 30 countries around the world.”

This movement is held up by more than light—it is grounded in labor. The ceramics and circuits were handcrafted by women’s cooperatives, local artisans, and community makers. They were not auxiliary to the process; they are its core infrastructure.

“The real transformation happens when people invest in building local green and creating a green economy,” Diaz noted. “We believe that instead of leaving these craftspeople behind in the campaign for climate action, we honor and celebrate them as the true heroes.”

For those of us in the art field, this installation prompts vital reflection:

Can public art do more than speak—can it step in, reshape, repair?

What does it mean to build something that endures, even when no one is watching?

And how can artists serve not only as storytellers—but as system-builders?

This convergence of artistry, advocacy, and local innovation reminds us that change does not always arrive as rupture. Sometimes, it takes root—deliberately and lastingly—in things shaped by hand, shared across homes, and carried into futures not yet drawn.

This is where the light lands—not just in records or headlines, but in the steady architecture of care. In the hands that shape it. In the lives it continues to reach.

Ayni Nuyda is an art consultant and the founder of Search Mindscape Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization that has dedicated itself to creating spaces that inspire interaction, collaboration, and engagement in the Philippine art community.

Liter of Light is a global grassroots movement that began in the Philippines in 2013 under the MyShelter Foundation, founded by Illac Diaz. What started as a DIY project using water‑filled plastic bottles to refract sunlight has grown into a low‑cost, open‑source and hand-built solar lighting solution using locally available materials and powered by local communities. The organization is a global ambassador for UNESCO’s International Day of Light and operates in 30 countries around the world.

Odangputik is an artist-run ceramics studio dedicated to bridging craft, culture, and advocacy. Founded by Ianna “odangputik” Engaño and Lin Bajala, it supports Philippine pottery traditions through collaborative projects, education, and community-rooted practice.