In an age where everything online and in our devices feels abiding, the very real threat of “digital decay” says otherwise.

There’s no denying that today’s digital landscape has drastically transformed the way we create, consume, and store content. Vast libraries can fit inside a single hard drive; search engines grant us access to billions of images in just a few words; repositories of information are neatly contained within a single URL. The digital realm is so prevalent, so easily accessible, that it might seem enduring—perhaps even eternal—but that’s never been the case. Digital decay always looms at the periphery, ready to strike in due time.

READ ALSO: Generative AI, Art, Humanity: Exploring A Tumultuous Relationship

What Is Digital Decay?

The name says it all, but to formally define digital decay, the Fountaindale Public Library District describes it as “the gradual degradation, obsolescence or corruption of digital data and assets.”

Growing up in a rapidly evolving world of technology, I was often told by older relatives that digital is forever, that we’re fortunate to have reached a period in history where anything and everything can be found online, or stored in the blink of an eye.

To a certain extent, that’s true—but this preserved information doesn’t appear out of nowhere. The vast digital landscape we live in is still being maintained by real people: from professional archivists in large institutions to web developers, and even individuals like you and me, who create content, store it on social media or personal devices, and share it with the rest of the community.

The Causes of Digital Decay

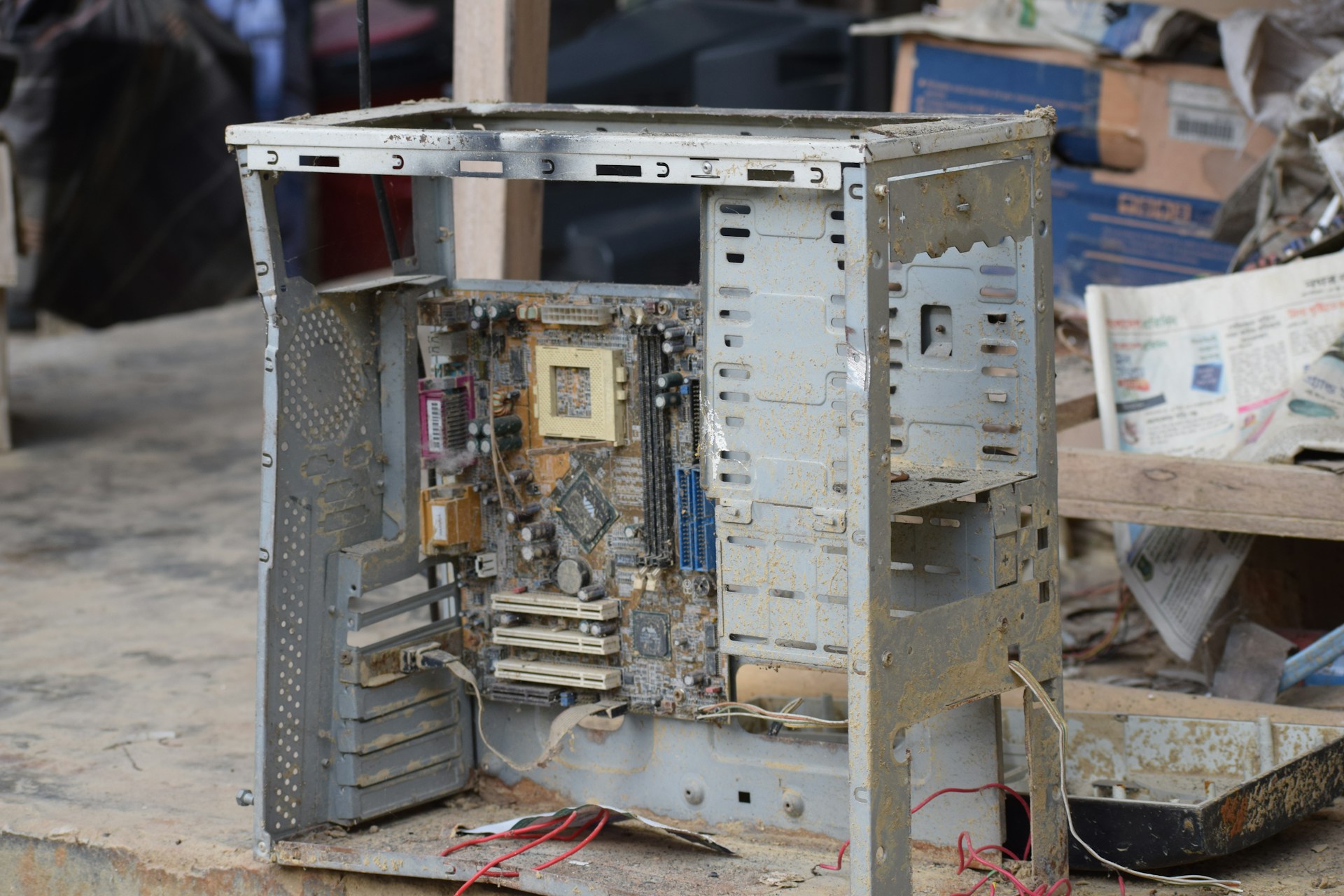

Over time, a great deal of digital content—if left unsupervised—will simply disappear. And I don’t think I need to illustrate this fact to those who have witnessed the era of CDs, floppy disks, bulky desktop computers, and the like.

There are a number of reasons why digital decay occurs. According to The Library of Congress, the life of storage media can shorten because of three factors: a lack of durability, usage and handling (the more you use a storage device, the more likely malfunctions and failures can occur), and obsolescence.

Obsolescence occurs when new technologies can’t read older media, lack hardware connections to support them, are missing drivers to recognize them, or lack the necessary software to access them.

Now you might think that uploading files online—either to a cloud, social media, or emails—would be the safer option. But as The Library of Congress explains, these aren’t reliable either, or at the very least, shouldn’t solely be depended on. It’s important to remember that the files you store in the cloud or social media can all be deleted the moment these platforms disappear or go out of business.

Digital Decay In The Online Sphere

Digital decay doesn’t solely affect offline content like personal files: it’s also prevalent in the online sphere. In May 2024, a group of researchers from the Pew Research Center released the study “When Online Content Disappears,” which recorded the concerning phenomenon of webpages and social media posts becoming inaccessible over time, also referred to as “link rot.”

While the researchers state that the word “inaccessible” can carry many meanings, they specifically use it to describe pages that no longer exist.

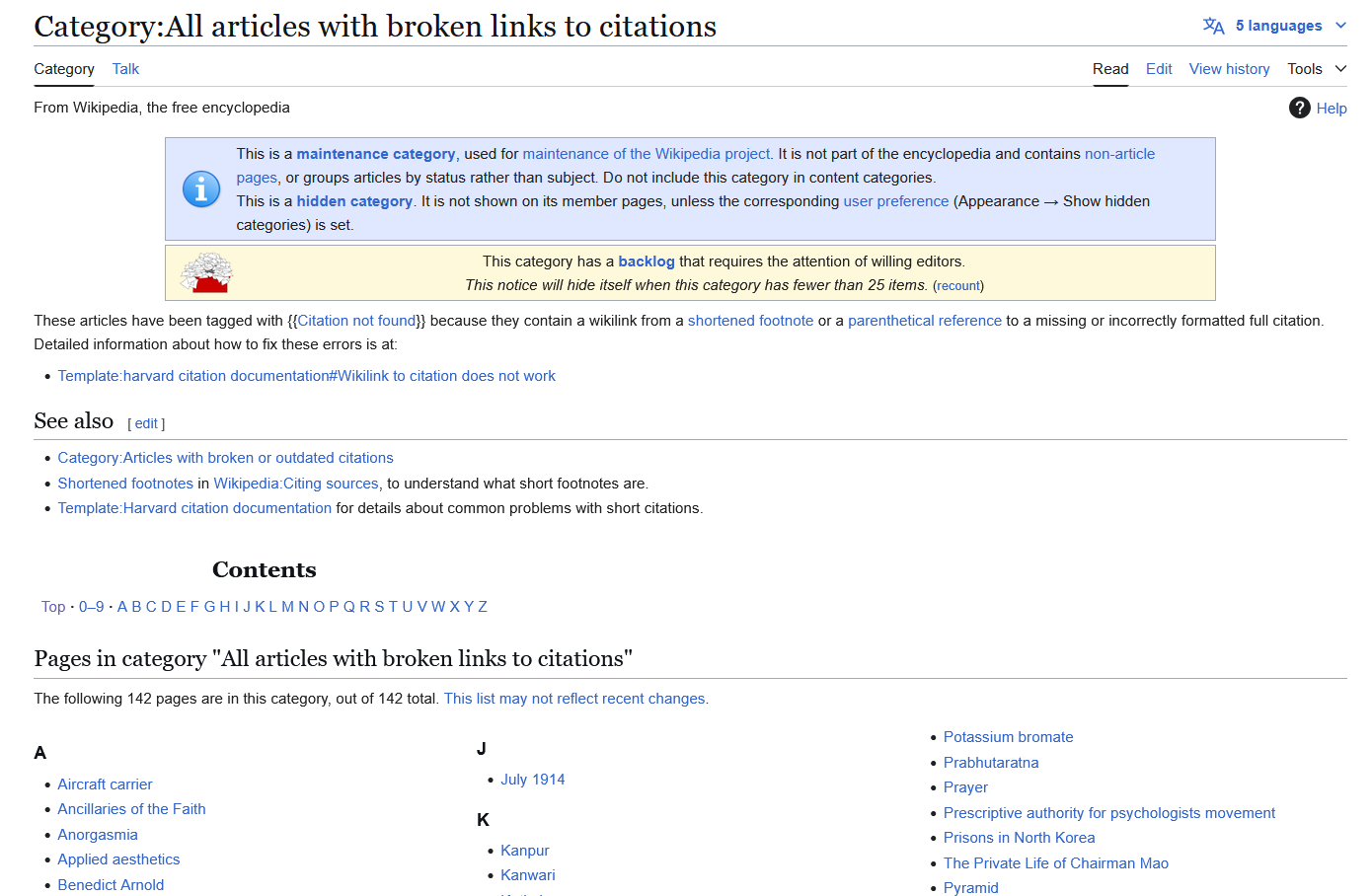

Webpages, News, and Wikipedia

The first part of their study involved sampling under one million webpages from 2013 to 2023 using the internet archive Common Crawl (with around 90,000 pages per year). 25% or a quarter of all the pages were no longer accessible as of October 2024, 16% of this total were individually inaccessible but found in functional root-level domains, while the other nine percent were inaccessible because their entire root domain (the website that hosts them) was no longer functional. 38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are not available today.

The results were sobering when they sampled 500,000 pages from 2,063 news websites classified as “News/Information” by the audience metrics firm comScore. The sites collectively contained more than 14 million links pointing to external websites. After tracking these links, the researchers found that five percent of them were no longer accessible, while 23% of the sampled pages had at least one broken link.

Reference links on Wikipedia face a similar issue. Researchers discovered that 82% of the 50,000 English-language Wikipedia pages had at least one reference link that pointed to a website outside Wikipedia. In total, there were roughly over one million reference links across all the pages, with 11% of them no longer being accessible, and another 53% of them having at least one broken link.

Social Media

For social media, the researchers collected almost five million tweets posted between March 8, 2023 to April 27, 2023 on the platform X (formerly known as Twitter). They monitored these tweets until June 15, 2023 (a span of roughly three months) to see if they remained available. By then, they found that 18% of the tweets from their initial collection were no longer publicly visible (either because their accounts went private, were suspended, or were deleted altogether). Half of the removed tweets became unavailable just within the first six days of being posted, while 90% became unavailable within 46 days.

These statistics are especially problematic if we’re trying to sustain a traceable web of information and knowledge. In a more casual situation, if you’re trying to show your friend a funny tweet or meme, and find that it’s gone, your next best option is hoping someone had the foresight to screenshot it and circulate it for posterity.

The Value Of Physical Media

Even in the digital age, analog and physical media still hold value. We see younger generations developing film, buying print magazines, and listening to vinyl. While this might seem like a step backwards, it’s actually indicative of the precarious digital world we live in.

Interestingly enough, and contrary to popular belief, physical media and artifacts don’t have to grapple with the kind of frailty digital media possesses, if (a big emphasis on this) they’re kept in optimal conditions.

A local example of this: most issues of the now defunct Rogue magazine are available through the platform Magzter. But what will happen when, perhaps years from now, the platform ceases to exist? Will anyone release digital backups of the magazine? Hopefully there’s someone out there with physical copies of the magazines, who may one day do archival work like Y2K Kabaklaan on Instagram and magasin archive on X.

As Teresa Soleau, head of Library Systems & Digital Services at the Getty Research Institute, details in an article: “While you are still able to view family photographs printed over 100 years ago, a CD with digital files on it from only 10 years ago might be unreadable because of rapid changes to software and the devices we use to access digital content.”

From Soleau’s experience, the degradation of digital files is a lot more “random”—and in some cases, fatal—than physical media. Degradation can be so bad that the file is lost completely, unable to be opened. It’s a nightmare for archivists, especially when they’re dealing with “born-digital” files that have no physical counterpart or incarnation.

“Most physical materials can survive a lot of abuse and still remain legible. If a corner is torn off a photograph or a page falls out of a book, you can still access the majority of the content,” she writes.

How To Be A Personal Archivist

The Library of Congress offers a selection of helpful resources on digital preservation to get the public interested in creating and nurturing their own personal archives. Their guide breaks it down into four steps to keep things simple.

Locate

You’ll need to locate your files before backing them up. If they’re stored in floppy disks, CDs, USBs, cameras, and other types of storage devices or clouds, it’s as good a time to start transferring them. Download your Instagram stories, save those articles you really enjoyed, take the precious video clips sent by friends in messaging apps, then gather them in one place (preferably your computer).

Decide

By this phase, you’ve likely gathered hundreds of photos, videos, documents, and the like in your computer. Now that you have everything at your fingertips, it’s time to decide which ones to actually keep. You’ll likely have multiple copies of the same file, and realistically, you probably won’t need everything—so choose the nicest ones, or the ones you really want to preserve (in other words, de-clutter).

Organize

Once you’re done weeding out files, it’s time to organize the selection. Label folders with specific and descriptive names, or use any system of organization that works best for you.

Save Copies

Finally, you’ll need to save multiple copies of these files in various locations. The Library of Congress recommends the “3-2-1 rule” of professional photographers when you do this. Make three copies of a file, save two copies on two different storage media, and save one in a location where you don’t live. The last rule is particularly important if your area is prone to natural disasters, and it’s one that many big institutions follow as a safety precaution.

Soleau adds another important step, which is saving files in widely-used or open formats. This will keep them usable or readable even as technology advances (of course, there’s no guarantee a certain format will remain the standard, but it’s still a good practice). These formats include TIFF or JPEG for images, and DOC or PDF for documents; you can view a more comprehensive list of these formats on the Fountaindale Public Library District website.

What We Stand To Lose

Our family used an old video camera throughout the early 2000s, which required small tapes to record footage. I think about the memories I shared with my dad and making home movies as a kid—a good portion of my childhood condensed into rectangular pieces of plastic. But now, I can’t watch or save them anymore, because our camera is broken and we can’t find a reader for these tapes. I can’t even remember all the contents of the videos we lost, and for now, it seems I may never know.

This anecdote is a microcosm of the losses (and potential losses) we face in a world that’s increasingly reduced to a string of codes—each one giving the illusion of forever. But as we’ve learned, digital content isn’t spared from the ravages of time.

If we don’t work to preserve our personal digital libraries, we could lose significant memories, records of the lives we lived. On a larger scale, society could continue to lose entire databases of knowledge, culture, heritage, and history—essentially, all the things that matter to us as a species. As we hurtle into an ever-changing, inexorably tech-centered future, perhaps the only thing left to do is to try preserving the valuable parts of these intangible worlds we’ve created.

Banner photo by Kelsy Gagnebin and feature photo by Fernando Lavin, via Unsplash.