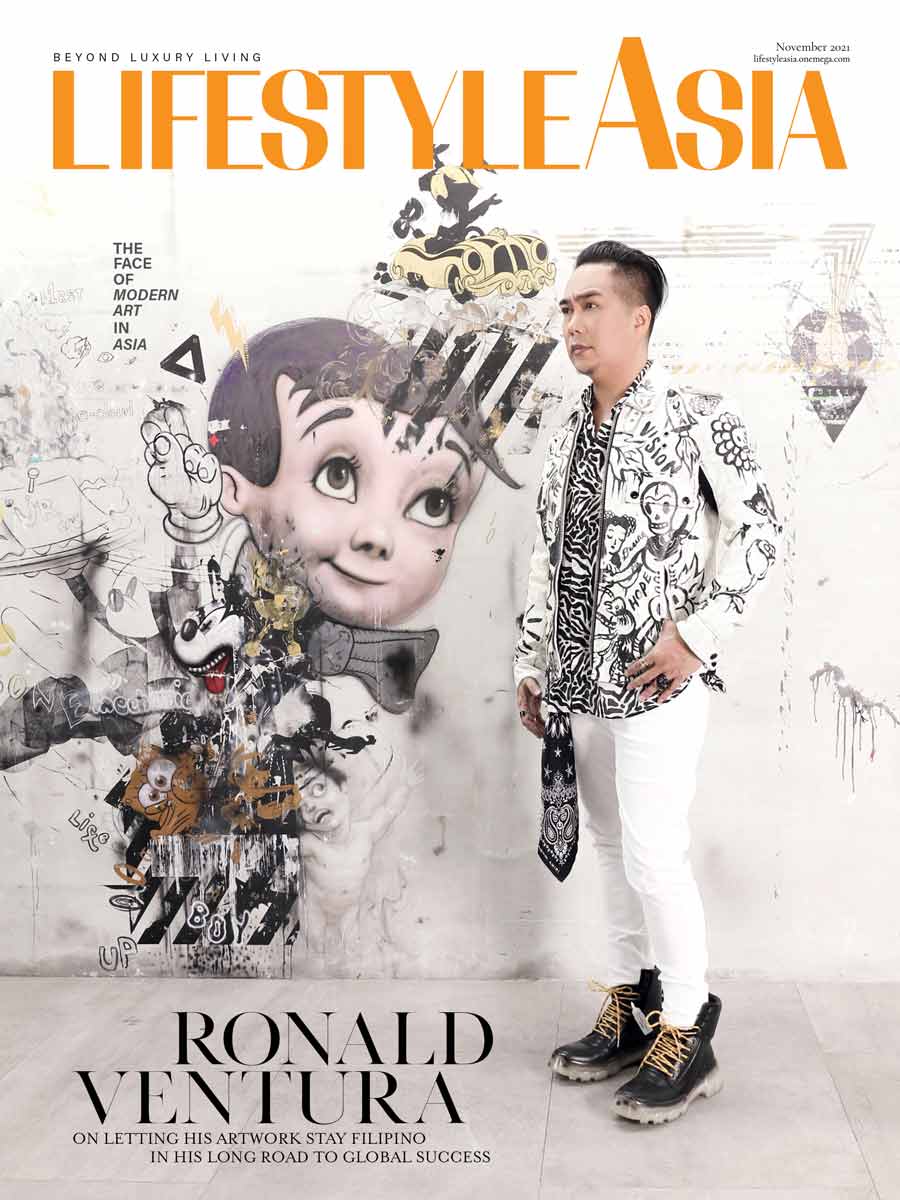

While his works sell for jaw dropping amounts all over the world, he doesn’t see being an artist as a profession but an ‘existential state.’

The mind of an artist is often a multi-layered enigma that reveals facets of itself through the art that’s produced.

One look at Ronald Ventura’s body of work and one immediately thinks of an opinionated, hardened individual that maintains a certain warmth and softness for the imperfect, the chaotic. There’s social commentary woven into his work, often seen as criticism that most definitely comes from a place of love—the tough kind but love all the same.

Nowadays, it’s hard not to talk about modern art in Southeast Asia without mentioning or even thinking of Ventura. His works have garnered quite a sizable following in the last decade or so.

“Party Animals” (2017), which features an image of a children’s party attended by forest and farm animals along with a couple of demons for good measure, was part of his Wild State of Mind solo exhibition at the Tyler Rollins Fine Arts gallery in New York.

It later sold for 19 million HKD at Christie’s in June of 2021. With this, there’s no doubt that Ventura is already getting the recognition he most definitely deserves. However, it’s something that he admits did not come easy to him.

“It was a long process,” he shares. “A long road to gain international acceptance.” His story wasn’t a romanticized, movie-like process where there was one big break that busted the doors of the international art scene open.

It’s one that is common to most artists coming from this side of the world—a lot of arduous work, honing one’s talent, and biding one’s time.

He even describes his work’s evolution as “a painstaking process of interpreting the images and goings-on around me.” There’s a bit of luck and good timing thrown into the equation as well. Being at the right time when the world is finally ready for something different and unexpected coming from far and exoticized Southeast Asia.

“When I was starting out, young artists needed to prove themselves first before they could even mount an exhibition in any of the galleries,” Ventura reminisces, noting how social media has made it easier for young artists to have and utilize a platform. During his time, it was much more different. “You had to earn your spot,” as he puts it.

The University of Santo Tomas Fine Arts graduate credits his international exposure to winning the grand prize of the Ateneo Art Awards back in 2005.

“I was awarded a studio residency grant to Sydney, Australia, allowing me to visit museums and galleries, to see artworks I used to see only in books,” Ventura says. Singapore followed soon after along with many international exhibitions.

And that recognition did not come from bending his work to conform to the West’s standards and presuppositions.

Letting art stay Filipino

Ventura’s work often features historical symbols seamlessly juxtaposed with contemporary pop culture symbols. Through them, he tells stories about the Philippines and its people’s multifaceted identity.

“Art in the Philippines has found a wider audience and a wide array of practitioners,” the artist explains, adding that this success did not come from producing what’s expected from this region.

His work is not something quirky or bucolic Western critics would often anticipate from Asian artists.

It took some time for the West to wrap its head around a different kind of art form coming from Asia, one that doesn’t pander to their taste and expectations. But when they finally got to it and the box they placed our artists in was finally made bigger and a little more diverse, they couldn’t get enough.

Ventura’s “Grayground” (2011) sold for over HK$ 8 million at Sotheby’s, setting a record at that time for the most ever paid for a Southeast Asian contemporary artwork.

This cemented his position in the international art scene. The graphite, oil, and acrylic piece’s success also pushed the door of opportunity a little wider for other artists from the region and allowed for more Filipino artists to break into the scene.

“Asia has had a long tradition of art-making that developed concurrently with (or even earlier than) that of the West,” Ventura explains. “We have our own sensibilities as Asians, as Filipinos. We need to embrace our own iconography, heritage, and how we view the world.”

Receptacle of images

The artist has come a long way from his childhood in Malabon in the 70s. It was a time when he perfected drawing Japanese robots he got to watch on television long before he could memorize the alphabet. As a young student, he would enter empty classrooms and fill their blackboards with drawings using chalk.

Even as success continues to come for him, Ventura remains to be the quintessential man of the arts. When asked what’s next for him, his focus remains on creation. “The dream is to finish a painting, and then work on the next one,” he says. “Being an artist is an existential state. It is not a profession.”

Ventura shares how the process of image-making, for him, is continuous. Being an artist, he says, means being a receptacle of images every single day, absorbing what you see in your surroundings, processing, and reimagining them into something tangible.

Even the seemingly mundane can spark inspiration.

“You walk in the city and you see someone talking on the cell phone. You see a dog, you cross the street, you see another thing, you hear something else…” he shares.

Despite the world coming to a halt during the pandemic, Ventura continues to get inspired and create. There’s a lot to be seen and felt in the stillness, after all.

Last year, artist and writer Igan D’Bayan shared Ventura’s pandemic project, a massive painting spanning 12 by 8 feet he christened as Paradise. It features a supposedly charming scenery: a waterfall in black-and-white along with several superimposed characters ranging from handsome animals to a depiction of Mickey Mouse near the center of the canvas.

When asked how the several bouts of lockdowns have been treating him in 2021, Ventura shared the same observations he had with D’Bayan back in 2020.

“During those long lockdown months, you get a glimpse of a cityscape without people — empty streets, darkened buildings, a deafening quiet,” he said, likening the experience to a Giorgio de Chirico paintings that depict mysterious and melancholy streets. “The paintings we used to see of cities without people, just shadows—that was our reality for a long time. Umiikot lang ‘yung araw. (Days are just passing us by.)”

As we all look forward to a seemingly far-off end to the ordeal, Ventura gives a dose of reality and how we have still yet to adapt to the ever evolving situation.

“Everything is changing—surroundings, climate, human interaction. We are still adjusting,” he adds.

A meaningful life

By now, it’s evident that Ventura’s way of life revolves around creation. Witnessing day to day life images and letting them flow like streams of consciousness helps find meaning.

“We live in a world where images flow like streams of consciousness. The disruption is not seamless, there are no subtle transitions; the stacking of images is jagged and abrupt,” he says. “But even if each work shows an overlapping of diverse images, there is a certain cohesion or visual solidarity.”

There is beauty in seeing the coalescing of things you didn’t think could come together. The pandemic and the current climate of the country has also given Ventura more time to reflect without losing affection for the place he calls home.

“Maybe it is something symbolic of the times we live in, but—speaking as an artist living in chaotic yet always cheerful Manila—one cannot help but be inspired by everyone and the every day.” It’s flawed but it has character and it’s rife with situations, faces, and even chaos that can inspire.

“Meaning is what you make of it,” Ventura concludes. The rest of the world can only nod in agreement.

Photos by MJ SUAYAN

Creative direction by MARC YELLOW

Hair and grooming by CATS DEL ROSARIO

Styling by ROKO ARCEO