Heritage ingredients in the Philippines represent our rich history and culture, but how we acquire them have come under threat.

The Philippines has a rich tapestry of heritage ingredients woven into our culinary history. These are sourced from the Philippines’ lush resources and are not just epicurean elements, but treasures that connect generations, communities, and traditions.

However, due to the modernization that exists nowadays, the customary ways of manufacturing heritage ingredients are slowly vanishing. While people strive to keep a part of our cultural identity alive, the country risks losing the ingredients due to the lack of interest to pursue their production.

“Tabon-tabon”

Michelin Guide described the tabon-tabon as a fruit that looks like a solid ball of wood, but within protrudes a brain-like structure. According to Chef Jose ‘Chele’ Gonzalez, the pulp and sap of the fruit is a bit bitter, but when mixed with other ingredients, the flavor blends in perfectly.

Tabon-tabon originated from Northern Mindanao and locals use it for the preparation of kinilaw, a Filipino raw fish dish. Its sap cancels out the smell of raw fish while its sap makes a sour-sweet taste when mixed with vinegar.

People confuse the fruit often with chico, but what sets it apart is that it has a hard shell as compared with the latter.

The tabon-tabon tree is an endangered indigenous resource. People typically find them in lowland forests, swamps, and along rivers. It is endemic to Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and the western Pacific Islands, aside from Northern Mindanao and parts of Visayas.

“Landang”

Cebu’s landang is one of the heritage ingredients in the country that are currently threatened production-wise. People also call it as native tapioca. The ingredient came from the trunk of the buri tree, processed to become a palm flour, where the landang forms.

The process to make landang is tedious as well. Makers select and cut a buri palm and divide the trunk into two to expose the core. The makers cut the core into thinner pieces once it shows and they will dry them under the sun for two to three days. They pound these into flour using a mortar and pestle, finely strained to remove fibrous elements. The flour is soaked in water for eight hours to clean it. The makers roast the flour in an oiled pan after draining and drying, until small lumps appear. This indicates that the process is done.

Natives usually combine landang with a Cebuano delicacy called binignit, similar to the already familiar bilo-bilo. GMA Public Affairs reported it almost resembles tapioca and sago, only with an extra nuttiness to its taste.

The ingredient is one of the primary sources of income to the locals residing in Barangay Tayud in Consolacion, Cebu. They hold the Landang Festival every May, where people showcase numerous rice cake recipes that use the native tapioca ingredient.

The cutting of buri forests for projects like subdivisions and malls threatens the production of the ingredient. People use parts of the tree as well for building and craft materials, so even landang-made creations are declining. The trees take decades to grow before people can use them again, and younger generations prefer to work in cities.

“Asin sa buy-o”

Asin sa buy-o is a sea salt that originated in the town of Botolan, Zambales. Salt makers make use of woven nipa to form the buy-o, a cylindrical container used to pack the salt. The leaves come from palm, rattan, and bamboo (pawid) sewn together like a sheet before makers form it like a circular tube.

Making the ingredient starts with the collection of sand into a mound and soaked with seawater to absorb salt. The team pours sand into a funnel where they add sea water again for a more concentrated brine after a day of drying. The mixture boils in a large cooking vat or kawa, while more seawater is poured into the funnel, resulting in sea salt forming in the vat. Producers then collect, dry, and pack the salt into the buy-o.

Content creator Erwan Heussaff said locals from the Panayunan community in the Sambali Beach Farm produce the salt. The salt actually had a history dating back to the 1800s according to Philip Camara, when his great-grandfather Nicolas established the heritage ingredient. He purchased land for rice harvesting and trading. In the process, he also divided a one-hectare salt bed between 25 families, 500 square meters each.

Heussaff reported there are only four salt makers who produce the Asin sa buy-o, including Nanay Editha. She became exposed to the process when she was nine, when her grandparents and mother were making salt at the time. Her daughter May followed the traditions.

Most younger generations are not willing to continue due to the arduous production process. Nanay Editha expressed hopefulness that the youth will learn it as salt makers are now diminishing in number.

Heussaff expressed in an X post that the best salt he tried locally was asin sa buy-o. “With only a handful of the salt makers left, we’re at the brink of losing it to time,” he said.

“Guimaras tultul”

Tultul from Guimaras (also dukduk) is one of the endangered heritage ingredients in the country. The salt involves a meticulous and labor-intensive process passed down through generations in Barangay Hoskyn in the town of Jordan.

Tultul are blocks of artisanal salt made with ashes from assorted driftwood or dagsa. Producers then drench the driftwood with seawater for several days. Workers will collect the concoction’s ashes in a filter called kaing, which will strain the seawater. They will boil the water produced in the process in a cooking pan called hurnohan. Salt makers will then add coconut milk to the liquid to enhance its flavors. The process goes on for five hours until moisture completely evaporates from the solidified salt. The finished product is a brick-like structure of salt, to which the makers package and sell in the market.

Salt makers do not produce the salt year round due to the lack of raw materials during the rainy season and the low salinity of seawater. They only produce the salt from December to May.

Lokalpedia, an entity that documents Philippine ingredients, said Emma and Serafin Ganila are two of the few families making tultul as well as the Padohenog family (as revealed by Heussaff on his Instagram reel.) The tradition’s survival is concerning, as younger generations may not possess the dedication to sustain the craft.

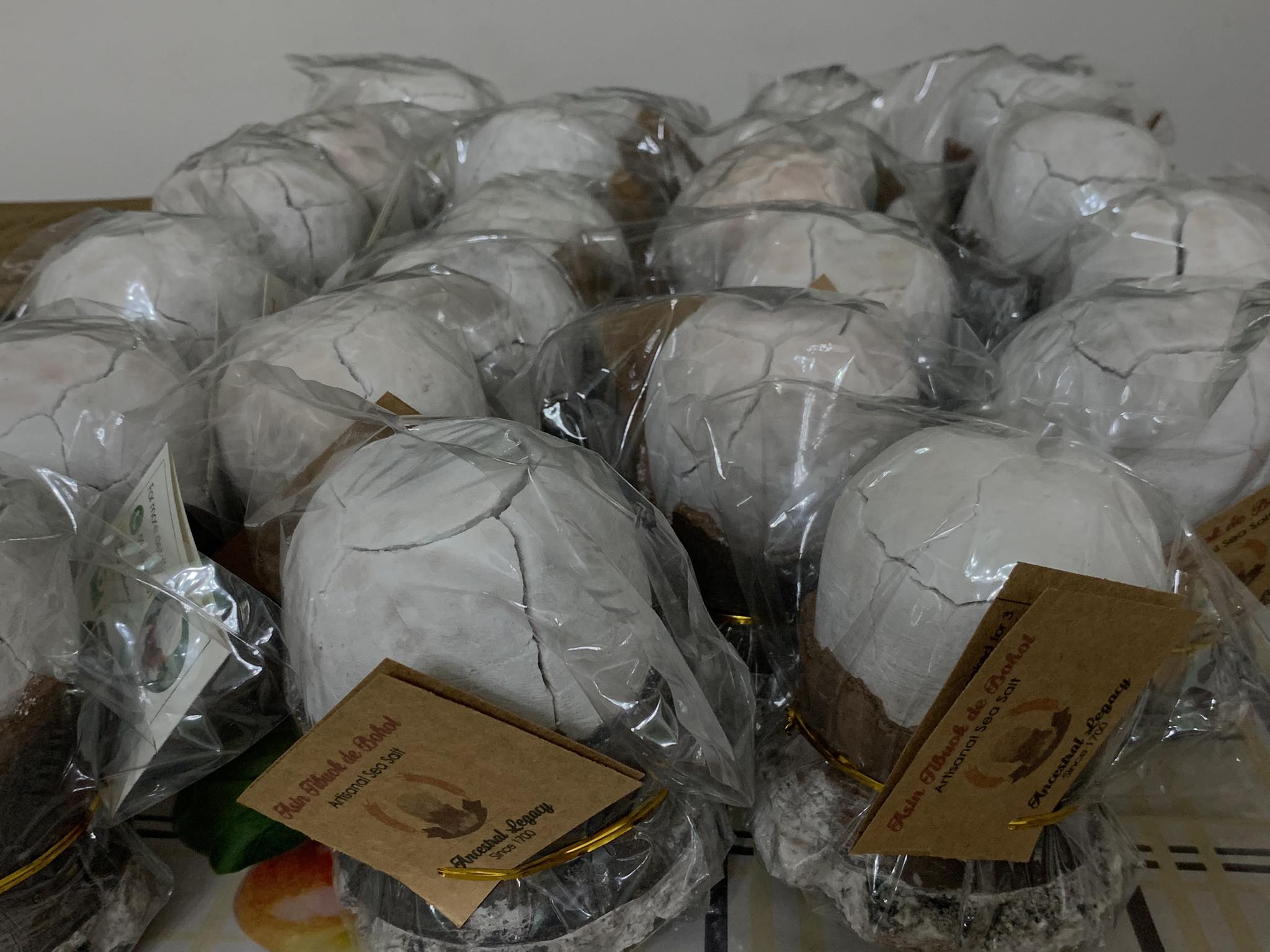

“Asin tibuok”

Bohol’s asin tibuok is shaped like a dinosaur’s egg. The locals of the town of Albuquerque or Albo/Albu produce the artisanal salt. This pre-Hispanic heritage ingredient takes more than a month to make, according to Romano Apatay, a salt maker from Bohol.

The salt takes three months to make. Its laborious process includes soaking coconut husks in a mangrove’s saltwater pool. Salt makers burn the husks and douse them regularly with sea water for three days. The workers place the highly-concentrated salty ashes over wood fire in clay pots called kolun and pour brine for eight hours. Taking extra care and time is crucial in these steps as the pots need to remain filled without cracking. The finished product is an orb of salt that looks like a dinosaur egg. Apatay said they make 150-200 pieces of asin tibuok in one production cycle.

Lifestyle Asia had the privilege to talk to Apatay and revealed that presently, four families immersed themselves in the business. “The families Manungas, Baluarte, Datoy, and our family administer the salt-making process,” he said.

Tan Inong Manufacturing oversees the process in Bohol through Nestor Manungas, who takes charge of production, according to a report by GMA News. Manungas and Apatay are actually cousins. “They [the Manungas family] pioneered the revival of its creation in the province,” he mentioned.

Apatay mentioned that most youths don’t immerse themselves in the production due to how stringent the steps are. “That’s our problem,” he expressed. “Our children and most younger generations don’t want to be involved. The craft is grueling to maintain.”

“We are thankful to the Manungas family because of their dedication to revive the craft,” he remarked.

Banner photo from Wikimedia Commons.