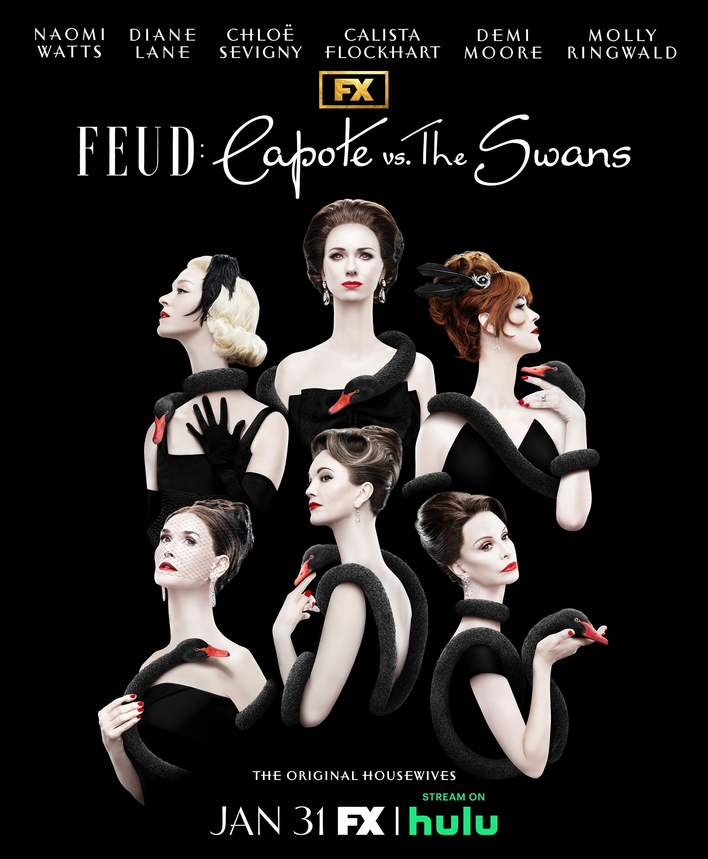

Get to know the socialites who befriended renowned writer Truman Capote—before shunning him for revealing the complications of their personal lives in his scandalous piece, “La Côte Basque, 1965.”

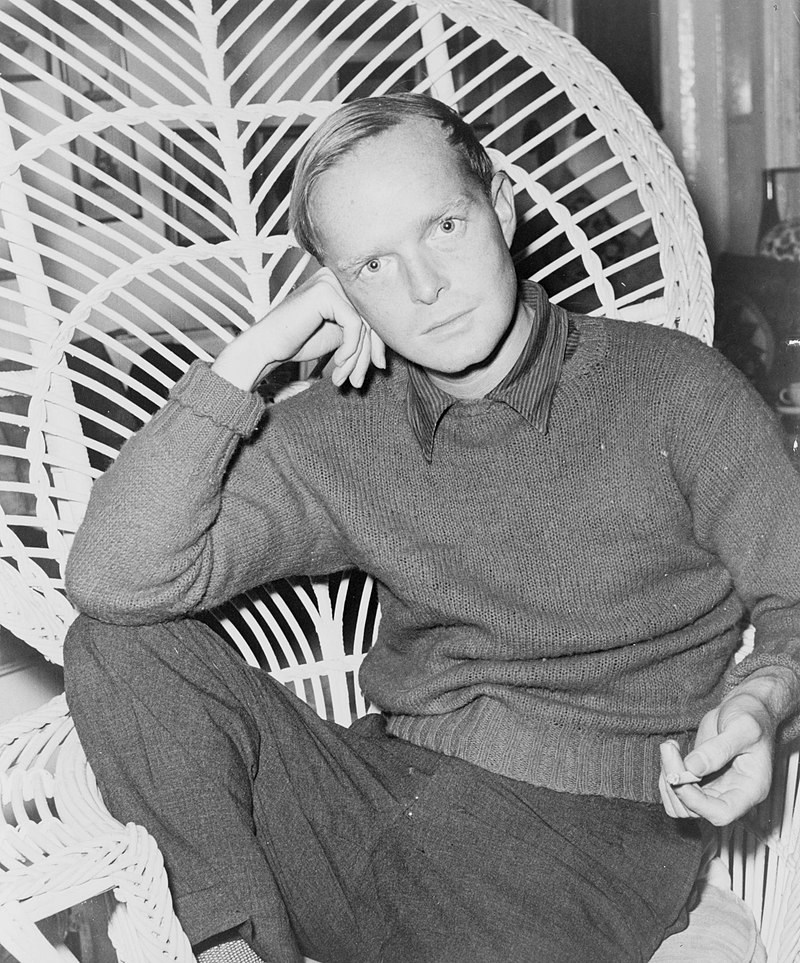

Truman Capote is one of the most celebrated writers in the literary canon, yet also among the most infamous. Once an introverted and lonely young boy whom relatives raised in the aftermath of his parents’ divorce, Capote grew to be a talented queer man whose social connections and writing fueled his life, reports Scarlett Conlon of British Vogue. Many people today remember him as the visionary behind the short story “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (the source material of the famous Audrey Hepburn film), as well as the nonfiction book In Cold Blood.

The latter piece—a harrowing account of the 1959 murders of a family in Kansas—skyrocketed Capote’s career, giving way to “international fame, sudden wealth, and literary accolades beyond anything he’d experienced before,” writes Sam Kashner for Vanity Fair. Yet it was Capote’s first published, semi-autobiographical novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, that began to catapult him into literary fame—providing him with opportunities to cultivate friendships with members of America’s elite society, reports Meilan Solly of Smithsonian Magazine.

Capote and His “It Girls”

The decades-long friendships that Capote would foster with some of the most elegant, wealthy, and high-profile women of his generation were a source of inspiration to him. However, this well of creative ideas would eventually lead to the untimely demise of the very precious connections they came from, as well as Capote’s glittering reputation.

The scandal between Capote and his group of socialite friends—whom he dubbed “The Swans” —shook American society in the 1970s. Yet it has also resurfaced in our contemporary milieu as the narrative behind the FX series, FEUD: Capote vs. The Swans.

But what exactly transpired between Capote and his gang of It Girls, and who were the glamorous and widely-admired socialites that comprised the group?

READ ALSO: Pen and Prejudice: Edith Wharton’s Complicated Legacy

The Piece That Started It all

In 1975, Esquire published a piece by Capote entitled “La Côte Basque, 1965” (which the publication has made available to read in full online). It was meant to be a sneak peek of sorts, one part in an unpublished book, Answered Prayers. Sam Kashner of Vanity Fair reports that the writer was incredibly proud to release the novel, bragging about how it would change the literary landscape. Capote classified it as a roman à clef: a type of story that discusses real events and people, but under invented names or pseudonyms. Indeed, the longform Esquire piece was exactly that.

Using code names (though sometimes mentioning the actual names of certain people), Capote wrote dramatic retellings of the scandals that surrounded his socialite friends, many of whom confided in him with utmost trust. These tales often came during meals Capote shared with them at La Côte Basque—a sophisticated restaurant where the rich and famous frequented, hence the title. Though he never mentioned The Swans’ actual names, the attempt to conceal their identities failed horribly, especially given how small the elite circle of America was.

Upon the release of the story, most of Capote’s friend group shunned him, some going as far as to ensure that he was cut off from the glittering society life he thrived in. In The Capote Tapes, a 2021 documentary on the writer, director Ebs Burnough stated that Capote “never recovered from it,” reports Scarlett Conlon of British Vogue. From that period onward, the writer would succumb to substance abuse, occasionally producing creative pieces in moments of lucidity, but never again as the artist he once was at his peak.

The Swans

Capote’s group of glamorous friends were at the very top of American society during their era, many of them from blue-blooded backgrounds. Life was like a movie with these women, who regularly dined with royalty (even married into such families), hung out with Hollywood big names, and starred in the front covers and “best dressed” lists of prominent magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. They were socialites in every way, and ones who fell for the charms of their entertaining and articulate friend Capote—much to their detriment, they would later find out.

Below are the six prominent members of The Swans, as well as how they ended up at the center of Capote’s incriminating “La Côte Basque, 1965”:

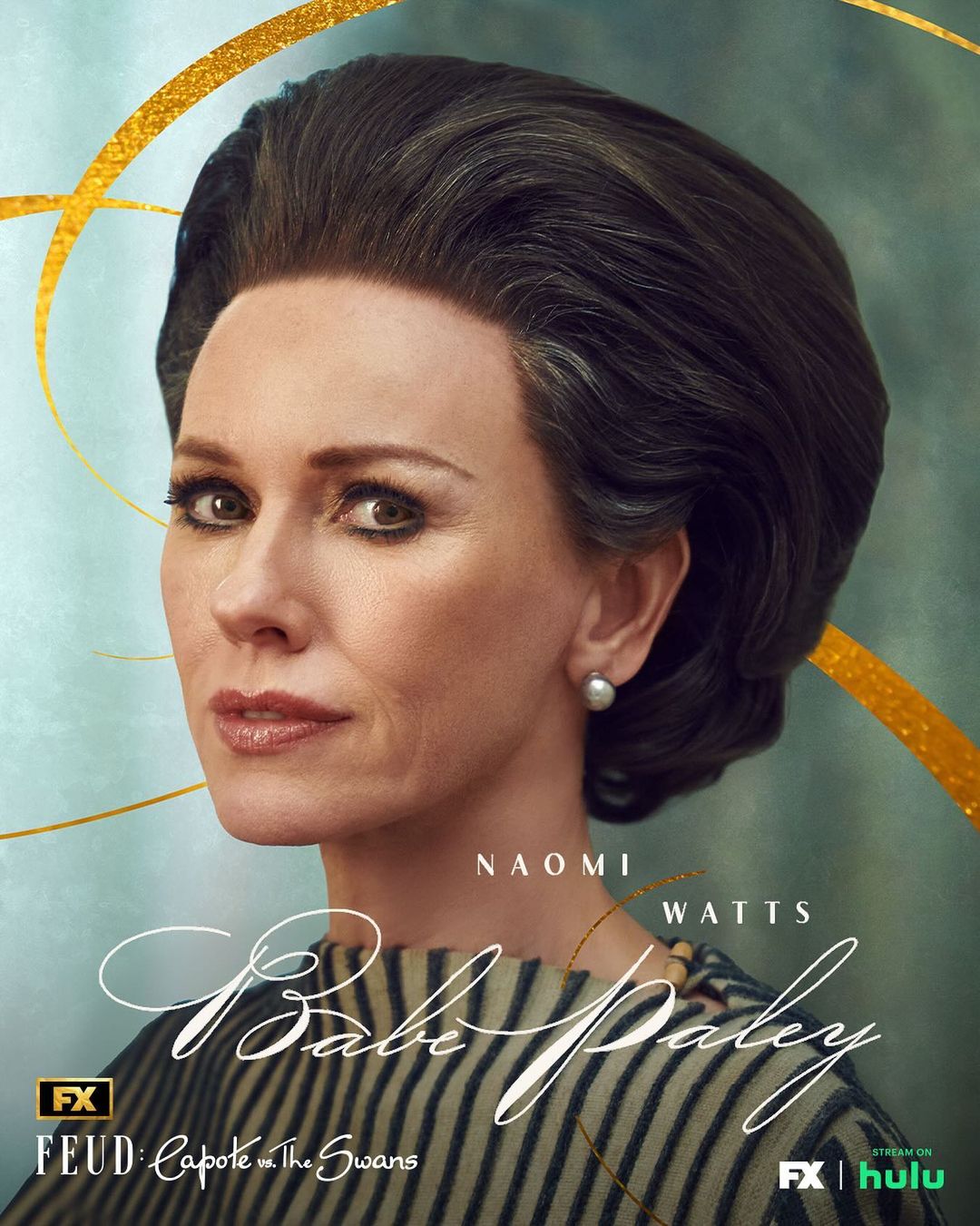

Babe Paley

Babe Paley was perhaps Capote’s closest friend in the group—or at least, the one that he admired the most. In a journal entry, the writer once wrote that her only fault was being “perfect,” reports Sam Kashner in a Vanity Fair article.

Paley was born Barbara Cushing in 1915 Boston, one of the daughters of esteemed Harvard professor and neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, according to Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair. As such, she lived the comfortable and glamorous life of someone of her social standing.

The Tastemaker

The stunning and elegant Paley would go on to become a fashion editor at Vogue before marrying and starting a family with Stanley Grafton Mortimer Jr. After their divorce, Paley married William “Bill” Paley, the chairman of CBS. She would continue to live the high life as a leading figure in New York society. Many knew her as a tastemaker with an admirable wardrobe collection, which would earn her a place in the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame 14 times throughout her life, writes Isiah Magsino of Town & Country.

Marital Struggles Gone Public

Sadly, Paley’s life was not without its challenges, as much of high society knew her husband Bill as a serial cheater. Paley would usually discuss her marital struggles with Capote, which became a focal point in “La Côte Basque, 1965.”

Biographer Gerald Clarke writes Capote’s move as an act of “revenge,” saying that he meant to depict Bill in an unflattering light, reports Meilan Solly. However, Paley didn’t take kindly to the publication of what she considered to be a private matter—though her husband’s philandering was an open secret, it wasn’t brought to wide public attention until Capote’s piece came out.

To make matters worse, Paley was grappling with terminal lung cancer at the time of the piece’s release. She never spoke to Capote again after the public humiliation his work brought to her, and passed away in 1978, according to Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair.

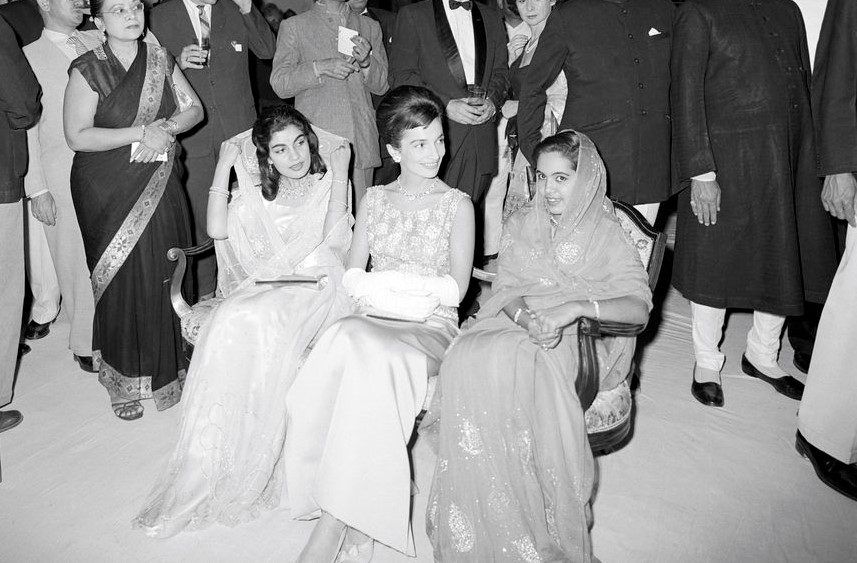

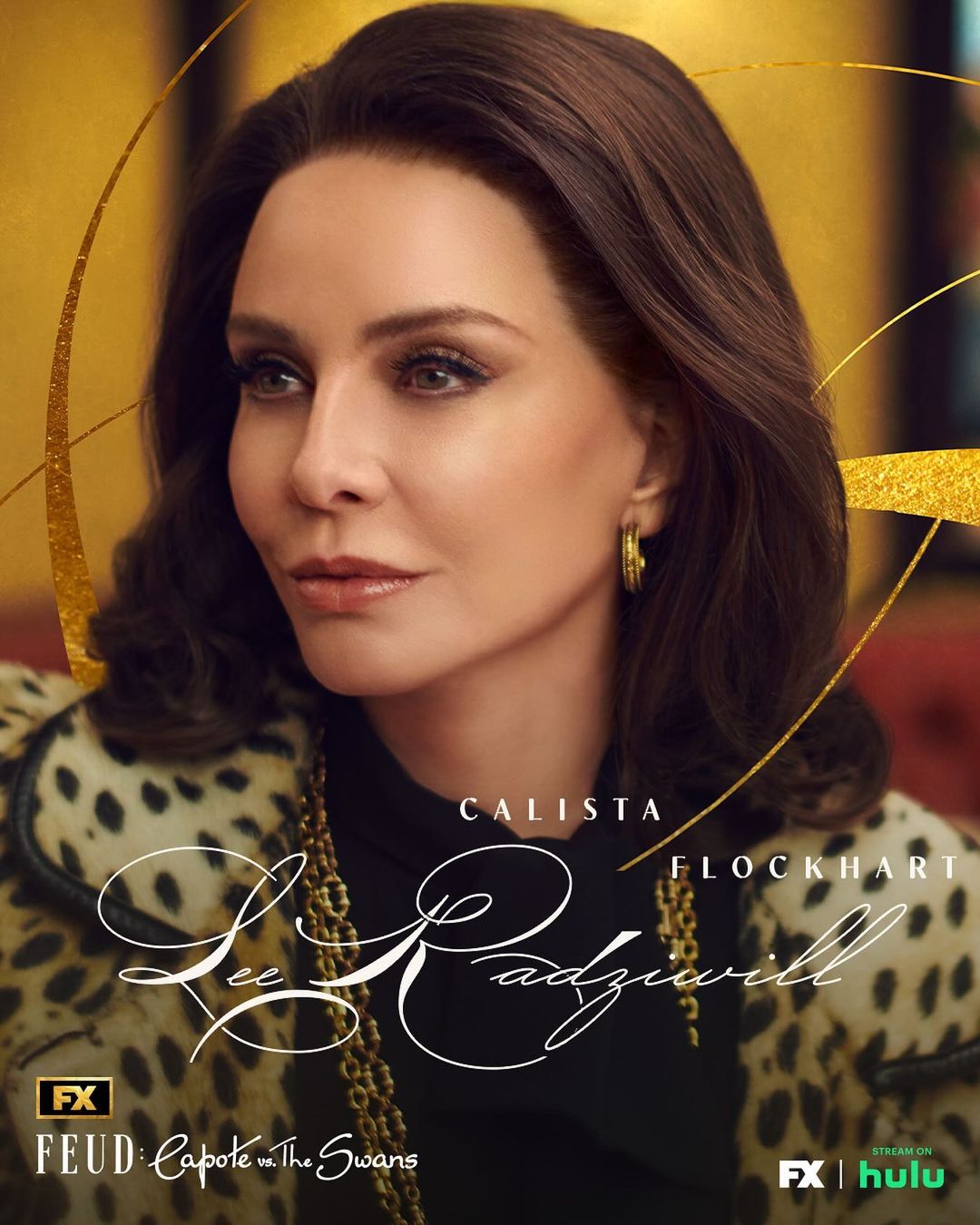

Lee Radziwill

Then there’s Lee Radziwill: the younger sister of none other than Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, both of whom were friends of Capote. Though Onassis was certainly the most famous of the two, Radziwill—born Caroline Lee Bouvier—was nonetheless a significant member of America’s elite circle. She even became a princess when she married Prince Stanislaw Radziwill in 1959, reports Alexa Dark of L’Officiel. The couple eventually divorced, and Radziwill moved on to become the wife of famous movie director Herbert Ross, whom she would also divorce, reports Liz Smith of Newsday.

Acting Gone Wrong

Despite the ups and downs of life, Radziwill garnered plenty of admiration as another fashionable muse. She also experienced a short-lived career in acting, starring in a number of big productions like 1944’s Laura and The Philadelphia Story. It was Capote who actually encouraged his Swan to pursue her dream of acting despite her lack of training. Unfortunately, critics didn’t enjoy her performances, giving scathing reviews that ultimately stopped her from continuing acting.

Capote’s ambitious plans and orchestrations played a big role in the quick death of her budding career, writes Mark Peikert for Town & Country. This would give way to a “rocky relationship” with the writer, as Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair reports.

Taking Sides

Fortunately, Radziwill wasn’t a focal point of Capote’s scathing “La Côte Basque, 1965,” according to Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair, though she did side with the rest of the gang when they ended their friendship with the writer. She even refused to testify for her former friend when he faced a lawsuit with Gore Vidal, who sued Capote for his unflattering depiction of a drunk Vidal getting thrown out of the White House during a party.

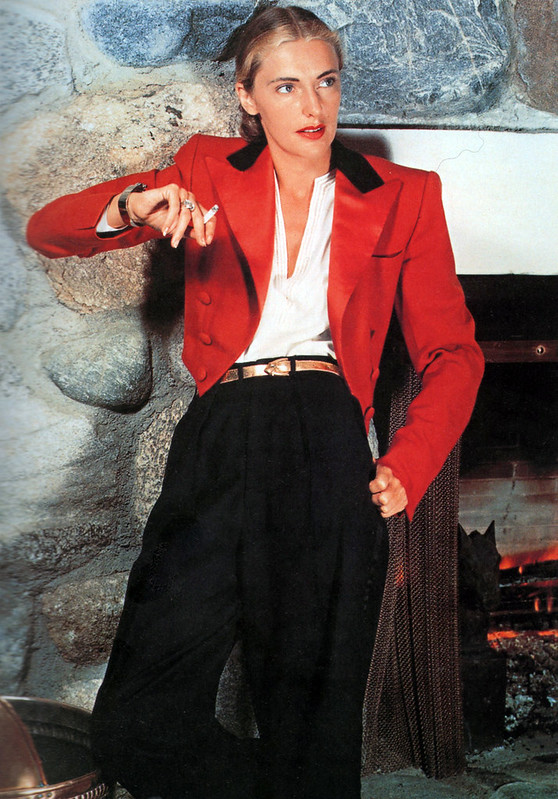

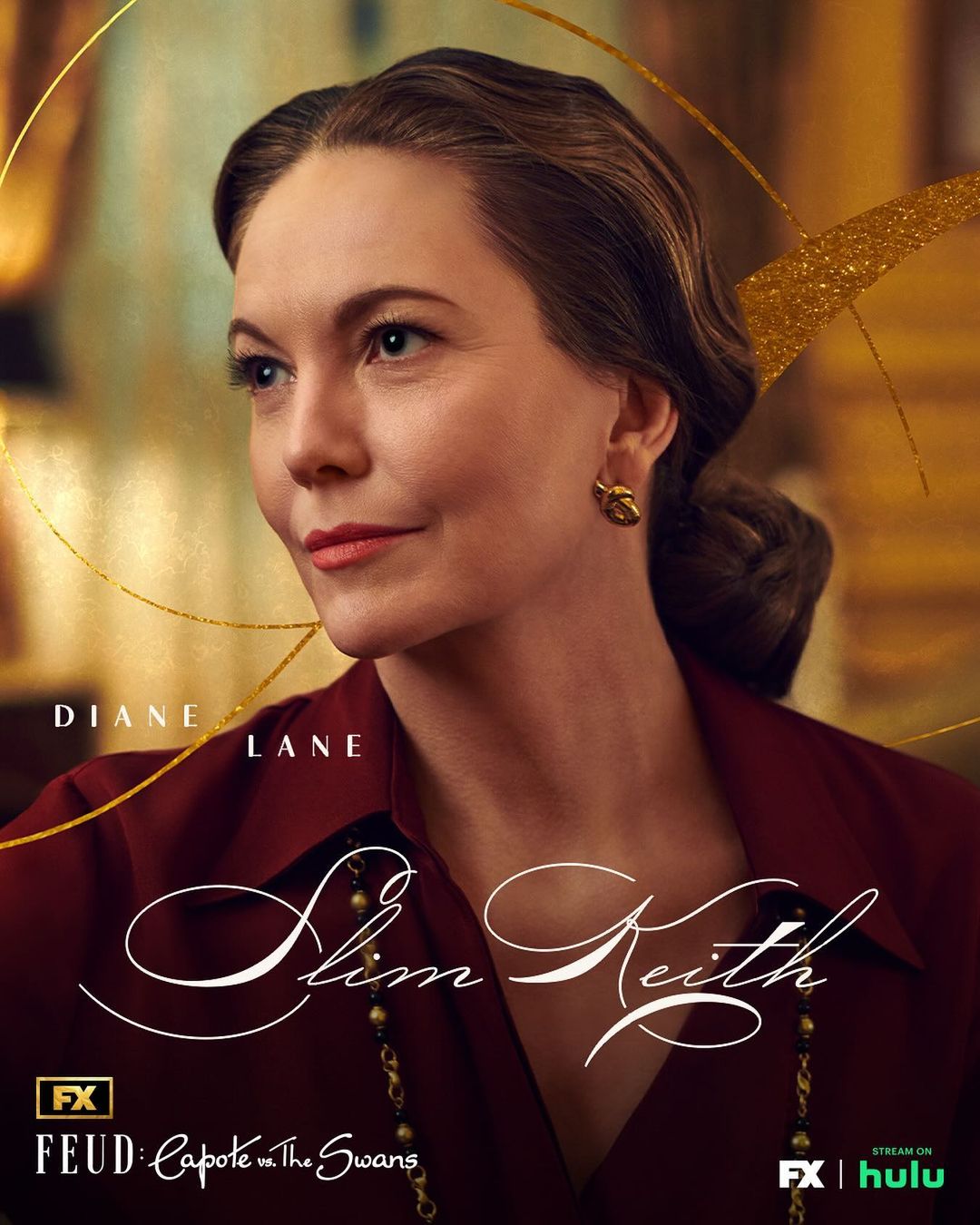

Slim Keith

Slim Keith was born Mary Raye Gross, the daughter of a well-to-do family led by her father, businessman Edward Gross. After her parents’ divorce, she moved to Death Valley at the age of 16, meeting publisher William Randolph Hearst and actor William Powell, who introduced her to the glitzy Hollywood scene, writes Isiah Magsino of Town & Country. From then on, Keith would hang out with the world’s biggest stars and icons, including Clark Gable (who took a romantic interest in her) and legendary writer, Ernest Hemingway (who reportedly pursued her as well).

Society’s Lady

Like her other Swans, Keith would enter marriages with influential and affluent men, including theater producer Leland Hayward, who brought Sound of Music and South Pacific to Broadway, according to Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair. She eventually got the title of “Lady” after marrying British banker Kenneth Keith, the Baron Keith of Castleacre.

Indeed, Keith may not have been born into the blue-blooded life many of her friends had, but she certainly made it to the top nonetheless. Like Paley, she fronted several magazine covers (including Harper’s Bazaar) and was the center of “Best Dressed” lists for years.

Unflattering Depictions

The stylish jetsetter met Capote in a dinner party, finding him to be a charismatic and great conversation partner. However, as with most of the writer’s Swans, she ended her friendship with him when he wrote about her as Lady Ina Coolbirth: a character who pursues older, wealthy men.

“I could understand why she married him—he was rich, he was technically alive,” wrote Capote in his piece. “Whereas Ina … Ina was fortyish and a multiple divorcée on the rebound from an affair with a Rothschild who had been satisfied with her as a mistress but hadn’t thought her grand enough to wed. So Ina’s friends were relieved when she returned from a shoot in Scotland engaged to Lord Coolbirth; true, the man was humorless, dull, sour as port decanted too long—but, all said and done, a lucrative catch.”

Keith considered filing a libel suit against Capote, yet ultimately decided to lead a quiet life (but not before cutting ties with Capote), report Lillian Gissen and Emma Saletta of Daily Mail.

Anne Woodward

Of all the Swans, it was socialite Anne Woodward who had suffered the most from Capote’s revelatory “La Côte Basque, 1965.” She was the black sheep of the group, a woman from humble origins who started her life as a Midwest radio actress and showgirl, writes Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair.

However, she later became the wife of wealthy heir William Woodward Jr. The two had a family together, and Anne began learning the ropes of high society, eventually becoming a notable figure along with the other women in Capote’s group.

The Alleged Murderess

Tragedy struck in 1955, when Anne accidentally shot her husband in their home, mistaking him as a “prowler” or burglar. She was acquitted of murder charges, though the story became a distressing part of Capote’s Esquire piece, as the writer’s characters accuse her character (Anne Hopkins) of intentionally shooting her husband and having salacious affairs with multiple men.

The way the society figures in Capote’s story describe Anne is dehumanizing, to say the least. Sadly, it’s difficult to separate fact from fiction: if the writer was simply reiterating actual conversations, Anne certainly received the most scathing depictions compared to her other peers.

“Ann realized something that only the cleverest social climbers ever do. If you want to ride swiftly and safely from the depths to the surface, the surest way is to single out a shark and attach yourself to it like a pilot fish,” writes Capote, in only one of many insulting descriptions concerning Ann.

Tragic Deaths

Before the release of Capote’s “La Côte Basque, 1965,” Anne committed suicide, reports Meilan Solly of Smithsonian Magazine. Presumably, the widow received an advanced copy of the story, and despaired at the social ruin it would cause her.

“Well, that’s that, she shot my son, and Truman murdered her,” her mother-in-law said, writes John Homans in a New York magazine piece.

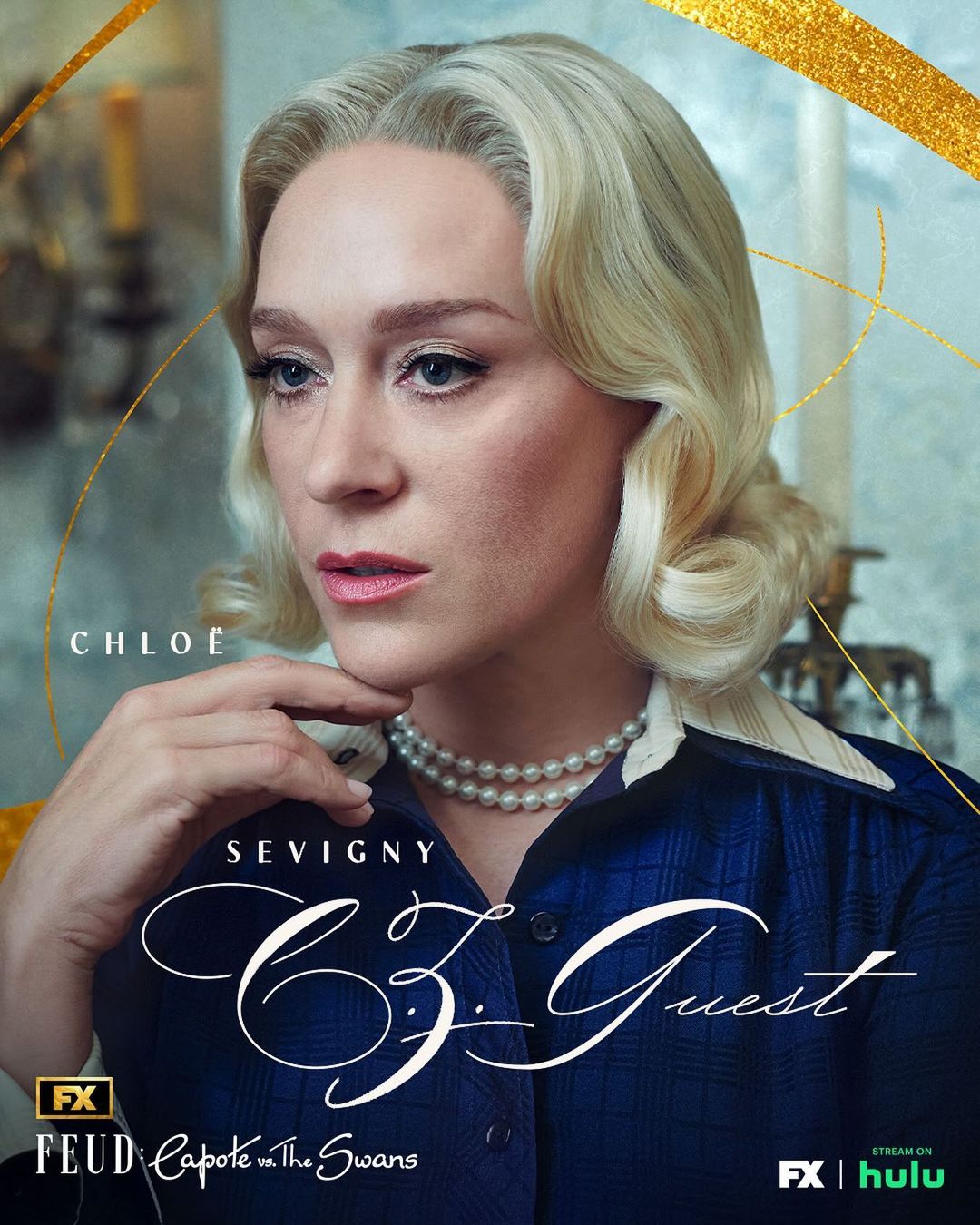

C.Z. Guest

C.Z. Guest, born Lucy Douglas Cochrane, is another Swan who thankfully wasn’t in Capote’s scandalous story, due in part to her more private nature. She’s also the only member of the group who forgave the writer after the incident, reports Chris Murphy of Vanity Fair.

Guest was the daughter of an elite Boston family, a girl who exemplified the blonde beauty of her time and pursued all the hobbies one would expect from a person of her pedigree. These included horseback riding and gardening, reports Fernando Snellings of WWD, two passions that she’d retain throughout her life.

Like her friend Paley, Guest became a fashion It Girl in the covers of magazines like Vogue, and even pursued a brief career as a showgirl, which she described as an experience she enjoyed “every minute of,” adds Snellings of WWD. She also became the muse of some of contemporary art’s greatest, including Salvador Dalí, Diego Rivera, and Andy Warhol.

Guest remained married to Winston Frederick Churchill Guest (who happened to be a relative of Winston Churchill), the British-American polo champion, until his passing in 1982, reports Christ Murphy of Vanity Fair.

Unveiling Society’s Secrets

There’s no doubt that Capote’s piece was groundbreaking in many ways, though not all of them good. Until the publication of “La Côte Basque, 1965,” no one dared to reveal the oftentimes embarrassing secrets and struggles of America’s elite, writes Scarlett Conlon for British Vogue. Doing so was, as Capote demonstrated, a form of social suicide. Yet Conlon adds that the piece became a progenitor of tabloids as we know them today: pieces that break the facades of the rich and famous, exposing them as no different than other people who struggle with life.

“The Swans were the high society who lived aspirational lives and were the envy of women across the States and elsewhere,” psychologist Carolyn Mair tells British Vogue. “Ordinary people would have read about these women and their lifestyles in the press and fashion magazines and would relate to them as if they were also their friends. The publication of ‘La Côte Basque 1965’ would likely have triggered a shocked sense of betrayal amongst the readers of popular and fashion press at the time.”

A Self-Inflicted Downfall

One might say that Capote was simply doing his job as a writer and journalist, seeking facts and revealing them to the public. Yet the story brings up questions about journalistic integrity or ethics. After all, just because one can write about something, doesn’t always mean that they should.

The writer passed away from liver failure and multiple drug complications in the home of one of his few remaining friends, Joanne Carson, in 1984, writes Meilan Solly for Smithsonian Magazine. As influential as Capote was (and still is), his actions left a ripple effect that ultimately led to the downfall of his status, career, and personal relationships.

Still, as Alex Belth writes in a recent feature for Esquire, everyone loves a good Icarus story. Capote flew too close to the sun, and paid the price for it—yet audiences continue to watch the spectacle, even years after the fact, fascinated with the lengths an artist will go through for their craft.

Banner photo via Instagram @feudfx.